News & Community

Reel People

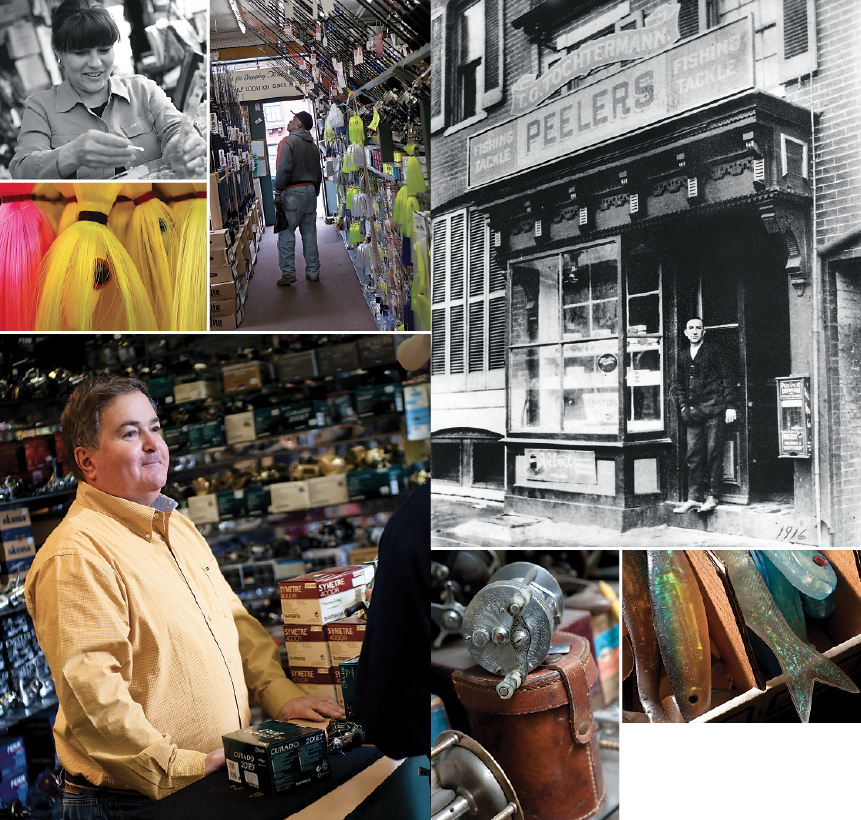

For nearly a century, the Tochtermans have been luring fishermen to an Eastern Avenue shop that’s become a local institution.

It’s late afternoon at Tochterman’s, and the venerable tackle shop’s neon sign flickers over Eastern Avenue. Its large-mouth bass, outlined in white light, splashes from an electric sea of green, hooked by some irresistible lure. The sign beckons fishermen of all stripes, hinting at pleasures to be found both out-of-doors and in the shop.

Entering Tochterman’s is like walking into a forest of fishing rods. Just inside the door, rods flank both sides of the center aisle, held upright in racks like those used for cue sticks. If it brings to mind a stand of bamboo, that isn’t surprising—the first fishing poles were made of that sturdy, pliable material; it’s what Huck and Tom used.

The narrow aisle leads to a counter—where a Tochterman has been selling bait and tackle and listening to fish stories for decades—and branches left and right to other aisles packed tightly and tidily with just about anything a fisherman might want. Besides 720 different reels, there are sinkers, lures, line, hooks, swivels, tackle boxes, fillet knives, boots, nets, Crawler Cribs, buckets, and waders. The selection of prepackaged bait includes Uncle Josh’s pork rinds and jars of preserved crawfish, along with Gator Minnow, Hawg Shad, Bass Assassin, and Power Bait Sparkle Nuggets.

Live bait prices are taped to a refrigerator: bunker chum $8/gallon, chicken necks $2.50, clam snouts $3.25, night crawlers $2.50, and bloodworms $9.99/dozen. The bloodworms sell best, with as many as 50,000 going out the door in a single week.

On any given day, you might find legendary anglers such as Lefty Kreh, visiting conventioneers, Hollywood actors, Beth Steel retirees, Fells Point residents, or even Saudi royalty browsing the aisles and chatting up owner Tony Tochterman and his fiancée, Dee Taylor.

They find Tochterman’s not via the Internet or through mail-order catalogs, but rather through a web of conversations and tips passed from fisherman to fisherman, father to son, neighbor to neighbor, writer to reader, concierge to hotel guest, and even doctor to patient.

In fact, that’s how the Saudis landed at Tochterman’s, which counts a number of Hopkins surgeons and specialists among its customer base. With the hospital just up the road, the docs sometimes recommend Tochterman’s as a good place for a patient’s family members to unwind. The Saudi royals come in to do just that. “They stay for hours, and their drivers come in with them,” says Dee.

“I’d say if their relative is in the hospital for 10 days, they’ll be in here five days,” says Tony. “It gives them a break from what they’re doing.”

At Tochterman’s, the prince gets treated the same as his driver and the same as the kid who rolls up on a bike, with a cheap rig and a bucket, on his way to Patterson Park. Age, race, and economic status seem to be irrelevant here—all that matters is a desire to fish.

Case in point: A young couple pulls out a credit card to pay for a night crawler ($2.65 with tax), and Dee tells them there’s a $5 minimum on charges. Obviously disappointed, they start for the door and Dee asks if they have any cash. They don’t.

Still, she hands the bait (which is packed in a Styrofoam container) across the counter.

“Give me the money next time you come in,” she insists. “You have to go fishing.”

You have to go fishing. Explicitly and implicitly, those words hover in the air and resonate throughout the shop. If someone doesn’t say them outright, chances are they’ll come to mind at some point during a visit, and even landlubbers and first-timers might find themselves thinking differently about fishing.

Pre-Tochterman’s, one might be inclined to chuckle at humorist Dave Barry’s quip that “fishing is boring, unless you catch an actual fish, and then it is disgusting.” But such talk is blasphemous inside Tochterman’s, where customers connect to their inner Hemingway or Thoreau in the abstract and to Tony and Dee in more tangible terms.

“I call them TNT, Tochterman and Tochterman,” says Bill Berry, over the phone. He’s the owner of Burke’s Restaurant and a customer since 1973. “Tony and Dee are dynamite, both of them are top notch. When it comes to fishing, they know just about everything, and they can get you anything.” (As Berry talks, he’s “out on the bay, fishing. We haven’t caught anything, but you know what they say, ‘A bad day of fishing is better than a good day of work.’”)

“They’re in a class of their own, top dogs,” says George Bentz, president of the Pasadena Sport Fishing Group. “They’ll help you any way they can.”

“They’re like family to me,” says Lefty Kreh, the world famous fly fisherman, who bought his first fly rod outfit at Tochterman’s in the late 1940s.

“I just love to be around there,” says Nooney Lamantia, who’s been coming to Tochterman’s for more than 50 years. Lamantia, a retired barber, comes in every two weeks to talk fishing and cut Tony’s hair. Not only that, he takes stock home to package and price. “If I can help, I do anything I can,” says Lamantia, who doesn’t charge for his services. “I do it as a courtesy, because I like them.”

That likely doesn’t happen at any of the big box, fishing/outdoor franchises that have sprung up in the past few years. Tony admits to some apprehension when such stores came to town, although it didn’t last.

“Our business has grown at a significant rate every year for the past 10 years,” he says. “We’re more than 400 percent higher—we’ve grown our business four times over—which is pretty remarkable. Dee and I realize that the only way we can survive is to offer some things the other stores don’t. Personal attention is one of those things.”

“We are here seven days a week,” adds Dee. “The both of us open up every morning and close up every night. If the store’s open, we’re here.”

“Our next day off is October 5,” says Tony. “That’s the first Sunday in October, after things slow down. It’s not like we’re looking forward to it, though.”

“Yes, we are,” says Dee, smiling.

“But that’s only because we’re so physically tired by then,” explains Tony. “See, we live and breathe this shop. When we say, ‘We’re going home,’ we mean we’re coming to the shop. If it weren’t for sleeping, there’d be no sense to have a house—other than to keep our three dogs.”

Tony and Dee live across the street from the store.

Tony Tochterman isn’t obsessed with fishing, per se. He’s obsessed with his fishing shop. When asked what he’d do if he weren’t running the store, he pauses, but not to consider his options; the question has no traction with him. “I never had a desire to do anything else,” he says. “Never. Ever. There was never even a thought of doing something else. I was born for this. I’ve worked here full time since 1958.”

Tony, who grew up in Rodgers Forge and graduated from McDonogh, was three and a half years old when he started at the shop, though he wasn’t on the payroll. “At that time, I had an infatuation with lures,” he recalls. “It was my job to put the boxes of lures in the display case by color and by size. That was neat and exciting to me, because they were like little toys.”

In the process, he eventually memorized their sizes, colors, and stock numbers. Over time, he kept expanding his knowledge, as his father, Tommy, groomed him for the job. “My father prepared me to do every job in this place,” says Tony. “There isn’t a job here that I haven’t done, including fixing the air conditioner and scrubbing the toilets.”

Besides that, he knows where everything, down to the smallest part, is located. When one of the store’s half dozen part-time employees asks where a certain piece of gear might be, Tony doesn’t hesitate: “We have it in the back. I think it is part 62. It’s on the top shelf. It should be blue print. About halfway back on the top shelf, you’ll see Penn parts. There’s a C ring next to it.” Sure enough, part 62, is exactly where Tony said it would be.

Tommy, who passed away in 1998 at the age of 86, would be proud. In fact, his presence is still keenly felt at the shop. As Dee talks about him, she constantly motions toward the spot he used to occupy behind the counter, as if he’d just walked away and will be returning any minute.

Actually, he’s still in the store. Tony points out a memorabilia case full of vintage reels, printed ephemera (an old brochure from the 1950s lists the hours of operation as 5 a.m. to 11 p.m.), a signed baseball (“To Tony, Your Pal, Ted Williams”), and various customer-service awards. The ashes of his father and mother are also in the case. “It’s actually comforting having them there,” says Tony. “Sometimes, I even go over and say a few words to them.”

There’s also a black-and-white photograph of the store circa 1916, the year it opened, in the case. In it, Tony’s grandfather, Thomas, stands in the doorway of the shop, next to the display window. An overhead sign reads, “T.G. Tochtermann. Fishing Tackle. Peelers.” (An “n” was dropped from the last name during World War I, because the original spelling was thought, by some, to imply support for the Kaiser.)

At that time, Tony’s grandfather managed a fish market at the harbor. The market often had surplus peelers (crabs, which are used for bait) and other seafood that spoiled because there was no refrigeration. Seeing an opportunity, Thomas brought the leftovers home—“with permission [from his boss],” notes Tony—and set up shop on Eastern Avenue, a heavily trafficked trolley route to the county.

“I never had a desire to do anything else,” he says. “Never. Ever. There was never even a thought of doing something else. I was born for this. I’ve worked here full time since 1958.”

Tony’s grandmother ran the store, while her husband worked at the fish market during the day. Besides bait, they sold hooks and poles, cigarettes, and candy. “It was a confectionery with fishing tackle,” says Tony. “People used to take the trolley to go fishing. They could jump off, get their stuff, get back on, and head out to their fishing spot.”

The candy sales dropped off, but tackle sales grew steadily. “My grandfather was smart enough to realize that people wanted better grade,” says Tony. “He had a lot of competition, but even back then, other stores didn’t give the personal service. He was devoted to it.”

Thomas worked seven days a week, so did Tommy, and their wives did likewise. All of them practically lived at the shop.

With such a family legacy, Dee was a particularly good catch.

Dee Taylor’s mother taught her to fish. She was just four years old when her mom started taking her to Loch Raven, where they sometimes stayed out all night if the fish were biting.

Dee was six when her mother brought her to Tochterman’s for the first time. “I remember Tony’s daddy,” says Dee. “He was very sweet, and he loved little kids. His wife was Antoinette—they called her Toni. That’s how Tony got his name.”

She didn’t meet him until years later, after her first marriage fell apart, and he was something of a fixture on the Fells Point bar scene. They immediately hit it off—being passionate about fishing and each other—and have hardly spent a night apart since. They’ve been a couple for 16 years. “Most people can’t be together 24 hours a day, but we thrive on it,” says Tony. “We may be separated for an hour a day, on average. We get better, the more we’re together.”

Like Tony, Dee smiles quickly and often, has a sparkle in her eye, and possesses an unflagging work ethic. Besides working the sales floor, she repairs rods and tends to the bloodworms (see sidebar).

But there are essential differences between the two of them, what Tony calls “good cop, bad cop. After all, when two people agree on business, one of them isn’t necessary. I buy too much, and she puts the brakes on me. She’s more about customer relations, and I like the paperwork. I’m thinking about inventory, and she’s thinking about taking care of that customer.”

Dee’s presence also ensures that the shop doesn’t become some sort of clubhouse for men, the sort of place where women might feel unwelcome. “Right away, I go for them,” Dee says, of the female customers. “And being a woman helps, although some of them don’t want anything to do with me, because they figure I don’t know anything. But when they see that I know what I’m talking about, we have fun.”

As a couple, Dee and Tony have fun in their own way. “This year, we took our first vacation in 15 years,” says Tony. “We were coming back from a trade show and decided to spend a few days in Ocean City. We got a room at the Hilton, and I called the shop and told the guys we wouldn’t be home for a few days.”

Like most folks, they went to the beach and went out to eat. But Tony admits they “spent most of the time visiting tackle shops and looking through the catalogs we picked up at the trade show.”

“But that’s us,” says Dee. “When new catalogs come in, we sit in the bed at night, watch TV, and discuss product.”

“Last night,” says Tony, “we spent three hours packaging swivels.”

The hard work pays off in various ways, some wholly unrelated to money. The memories are priceless. Like when a guy asked Tony for a two-ounce sinker and then, holding it in his hand, asked, “Got any heavier two-ounce sinkers?”

Or after Tommy’s heart attack, when two women, upon learning he was hospitalized, dropped to their knees and prayed for him. Right there at the counter.

Or when five generations of a family came in at the same time. The eldest insisted that the newborn be brought to Tochterman’s on the way home from the hospital.

And, of course, there are the kids. “When that child catches his first fish, there is a look on his face that you won’t forget,” says Tony. “I see children, whether they’re five or 50, coming in here every day with that look.”

With no children of his own to groom as his replacement, Tony isn’t sure what will ultimately become of the shop. He’d like to hit the 100-year mark and see where things stand.

“If I had children, I’d have a hard time bringing them into this business,” he says. “Most people would think it’s too many hours for the return on the investment. I may have been drafted into the job, but it’s also been my choice. I know of nothing better. And I don’t know who would take this over. You’d have to be out of your mind.”

There Will Be Bloodworms

There Will Be Bloodworms

Dee Taylor takes reservations for her bloodworms. With so many worms selling at the shop, it’s a good idea to call ahead, so Dee maintains a reservation book that “guarantees if I have the worms those people will get them first.”

“I can go through 8,000 worms a day,” she says. “We’ll go through 20,000 in a week. My biggest week was 52,000 worms.”

They’re sold over-the-counter, by the dozen. Because Tochterman’s doesn’t wholesale or ship bait, people come from as far as North Carolina for these worms. “If you want, you can buy 20 dozen, but you have to come to the store,” says Dee, who runs the bloodworm operation.

Starting in April, she orders worms from diggers in Maine and Canada. “They have to be dug near the coastline every single day, and only when the tide goes out,” says Dee. “The quality of the worm you get depends on the diggers. The only thing we ask for is a good worm—no crappy worms, no dead worms. But it’s just like buying something at a fruit stand. Some of the grapes are perfect, some aren’t. You have to weed them out. That’s what we’re known for, selling only good worms.”

The worms are shipped to Tochterman’s, packed in wet grass or newspaper, in cardboard flats or styrofoam boxes. “I don’t want lids on them,” says Dee. “I don’t want any suffocation. If they get stuck somewhere for a day or two in transit, they’ll suffocate, and it’s a waste of worms. I don’t want them to die for no reason. It sounds corny, but it really bothers me. It’s bad enough that someone cuts up a worm.” (Over the years, she’s also found the occasional live crab, clam, or oyster that’s gotten inadvertently packed with the worms. She keeps them alive in a tank in the back room.)

Dee removes the worms from the packing material and transfers them to a saline solution in shallow tubs, being careful to match the temperature and salinity to the worms’ native environment. Once in a while, she’ll come across a giant worm, a real whopper that stretches to three feet in length. She has a stack of Polaroids to prove it. Dee also adds food and vitamins to their water, which she changes once or twice a day. The Arizona Iced Tea jugs in the refrigerator are full of salt water for the worms.

Dee keeps a close eye on her worms. “I count every worm that gets sold,” she says. “Every worm that leaves this building is handled by me.”

And bloodworms can bite. Dee describes it as feeling like a bee sting, but then it numbs. “I’ve only been bitten twice in 15 years,” she says. “Considering all the worms I’ve sold, that’s pretty good.”