News & Community

Matter of Life and Death

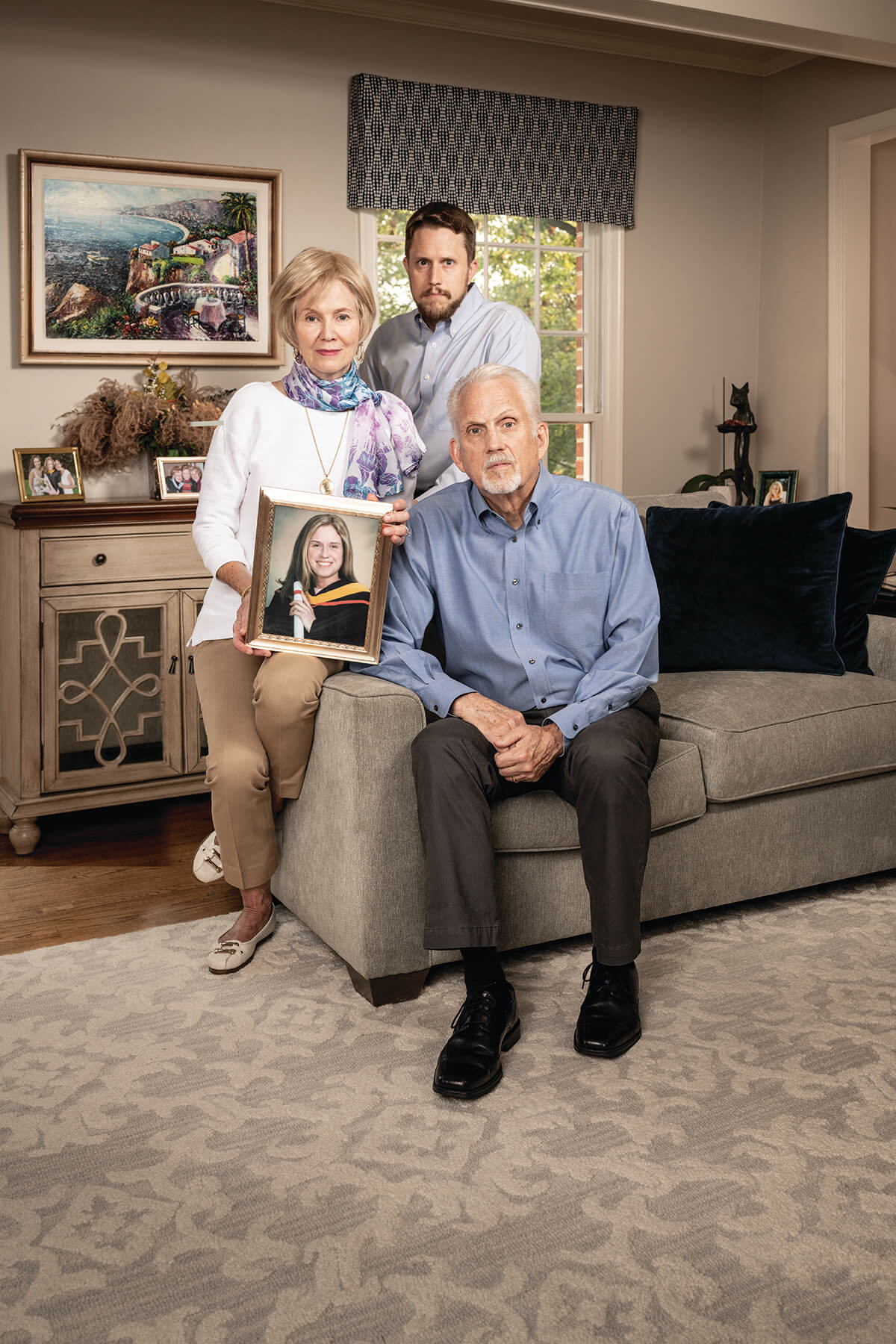

After losing their daughter to dating violence, Bill and Michele Mitchell share their story to save others.

[Editor’s Note: October is Domestic Violence Awareness Month. At any time, if you or anyone you know needs help, call: National Domestic Violence Hotline: 800-799-SAFE (7233) Maryland’s 24-hour Hotline, House of Ruth: 410-889-RUTH (7884)

Bill Mitchell will be the keynote speaker for “Voices: When Relationships Hurt,” a free virtual event on October 13 organized by CHANA—The Associated’s Jewish community response to the needs of people who have experienced abuse or trauma. For help, call 410-234-0030.]

As a graphic design student at Maryland Institute College of Art, Bill Mitchell had always admired the work of eminent illustrator Norman Rockwell.

Mitchell was such a fan, in fact, that, in 1972, the summer before his senior year, he and his then girlfriend (now wife), Michele, drove to Stockbridge, Massachusetts, specifically to meet the artist whose depictions of everyday life made him the consummate capturer of Americana.

Now, sitting in the family room of their well-kept brick Colonial on a quiet cul-de-sac in Ellicott City, with Norman Rockwell’s biography and a coffee table tome of the artist’s works high on a bookshelf, the Mitchells share their own life story, which, at least until late spring of 2005, could have been the subject of a Rockwell painting.

The couple, who were high-school sweethearts, had a daughter and a son, what Bill says is often referred to as “the million-dollar family.” Their older child, Kristin, and son, David, both blond and blue-eyed, were four years apart. Kristin and David played with Barbie and Ken dolls together, enjoyed road trips and family vacations to Hilton Head, and played school, with Kristin teaching David algebra in the basement. They adored each other. “It was one of the greatest joys of our life how well they got along,” says Bill.

In the spring of 2005, life was humming along according to plan. Bill had a fulfilling career as the creative director at an advertising agency in Columbia; Michele was a reading specialist at Glenelg Country School; David was a senior at Loyola Blakefield and would soon be off to college; Kristin was graduating from Saint Joseph’s University in Philadelphia and had a promising position lined up at General Mills.

“Our lives were pretty nice,” says Michele wistfully.

And then, on June 3, 2005—20 days after watching Kristin turn her tassel at graduation—the bubble burst. On that rainy night, after dinner with his parents at a restaurant near BWI airport, Bill was contacted by a Howard County detective who said that she needed to speak with him in person. They met at a Giant market near the family home, where she informed him that Kristin had been murdered—stabbed 55 times they later found out—in her suburban Philadelphia apartment by her boyfriend. The authorities later learned she was trying to break up with him at the time.

The one and only time the Mitchells had met the killer, whom Bill describes as “28, six-feet, and gym-rat solid,” was at Kristin’s graduation. He and Bill had shaken hands. A fleeting thought entered his mind, “I’d never want to tangle with this guy,” he recalls thinking.

At the crime scene, in the kitchen, where the stabbing started, there was a pad of Post-its, a list reminding Kristin of the thank-you notes she needed to write for graduation gifts. Also sitting on the kitchen counter was a pan of brownies and muffins she’d baked—all emblems of the quotidian life she’d been living just hours before.

THE ONE AND ONLY TIME THE MITCHELLS MET THE KILLER . . . WAS AT KRISTIN’S GRADUATION.

That night, after learning the news, Bill stood in the corner of the same room where he sits now, to break the news to Michele, David, and his parents. Even as he was sharing the unimaginable, through his fog of shock and pain, bereft and broken, he was trying to find a path forward. He knew then that he had to turn this tragic event into something good.

“That first night, I remember thinking that this is a responsibility and somehow it will become an opportunity,” says Bill. “That’s just some teletype that ran through my mind. Pretty quickly I realized that you could go into a cave and just do as little as possible and ride it out, or you could use your grief as energy.”

It’s been 16 years since that night, and each of the family members have metabolized their grief—so vast and unyielding—in different ways.

“We’ve handled our grief very differently,” says Bill. “If I’ve learned anything about grief, it’s that people have to allow other people to find their own way to deal with it, because you are handed something that you don’t really want, and you can’t get rid of it and you can’t fix it—no one can fix it.”

Michele speaks out sparingly, instead letting Bill serve as the family spokesperson. She chooses to cherish the memories.

“My way of grieving is just keeping aware,” says Michele, who believes that she’s gotten “signs” from Kristin since her death, from unexplainable electrical occurrences in the house to a cat, Kristin’s favorite animal, suddenly appearing under a bush a few weeks after Kristin’s murder. (“In a religion class she had once written that if she died, she’d want to come back as a cat,” explains Bill.) The Mitchells adopted the cat and named it Bear—Kristin’s nickname.

“Talking to Kristin in my own way and knowing with our beliefs that we will see her again brings comfort,” says Michele, welling up as she speaks. “I just can’t keep reliving it. It’s just too heartbreaking. You just keep thinking, ‘Kristin would be 38 on her birthday. She most likely would have been married with children and we would be grandparents.’ You think about the ‘what ifs.’”

David, now 34, a management consultant at Deloitte and once a board member of the now-defunct Kristin Mitchell Foundation, which was started by her college friends, has moved on with his life, marrying a young woman in 2019 whom Bill says, “has many aspects of Kristin’s outgoing personality.”

On occasion, he also speaks to young people about his sister’s story. And true to the “teletype” in his head, Bill has turned his daughter’s death into a near messianic mission. He shares the story of Kristin’s brief but beautiful life—and horrific death—anywhere he can, in school auditoriums, at domestic violence awareness events, on his podcast, in a book he self-published, to keep others from suffering the same fate.

On this spring day, neither Bill or Michele wants to talk about the details of Kristin’s murder or relive the tragedy of that night, though Bill writes about it with brutal honesty in his book, When Dating Hurts.

Though few details are spared, neither of them will refer to the killer by name (the book uses a pseudonym). They do not want to risk retraumatization or bring notoriety to the man who, thus far, has served 16 years of a 15-to-30-year sentence for second-degree murder.

Instead, they prefer to call him “the killer” or “the monster.” Says Bill, “I barely think about him—he was the author of the worst chapter of our lives.”

What does interest them, especially Bill, however, is speaking about the subject of domestic violence, of which dating violence or intimate partner violence is a less-discussed facet. He’s quick to reel off facts and figures, which he recites by heart. “One in three women experience physical violence from an intimate partner during their lifetimes, and typically it happens between the ages of 16 to 24,” he says. Then he sighs. “How many times have I said this?”

Through the years, Bill has given countless speeches at high schools, on college campuses, and with community organizations, including 2,100 teens at area high schools in St. Mary’s County in 2018 and a single audience of nearly 1,000 at a House of Ruth event at M&T Bank Stadium in 2007.

Five years ago, for the first time, he sat down to write about his effervescent daughter—a devoted equestrian, a talented flutist, and caring friend.

“In the summer of 2015, I wrote articles on LinkedIn,” he says. “I was curious to see what the reaction might be. Even though it’s for business, a lot of people have kids. I had 500 connections at that time, which is nothing. But I got all positive comments and ‘likes,’ and some of the comments were that I had taken a difficult subject and written about it beautifully.”

“IF I’VE LEARNED ANYTHING ABOUT GRIEF, IT’S THAT PEOPLE HAVE TO ALLOW OTHER PEOPLE TO FIND THEIR OWN WAY TO DEAL WITH IT.” —BILL MITCHELL

Although he didn’t know that his articles would become the springboard for the book, he kept learning about domestic violence by speaking with experts at a national and state level, meeting survivors and their families, and trying to figure out clues that may have been missed.

“Early on, I kept notes when I was on the phone with the prosecutor,” he says. “I would be on the phone writing feverishly to keep up. I didn’t see a book coming for the longest time, but I knew that I wanted to keep all this information and that someday it would be valuable. We had accumulated so many experiences and so much knowledge, and I thought what a crying waste it would be to not share it.”

In May of 2020, after four-and-a-half years of writing, he finally published When Dating Hurts. The book details every aspect of the days leading up to Kristin’s death, her funeral, the years that have followed, and the warning signs.

Today, Bill can recite those warning signs with authority (red flags include emotional and psychological abuse such as isolating the victim from family and friends, extreme jealousy and possessiveness, and physical and/or sexual abuse). As he ticks off the list, he double checks the notes scrawled across a legal pad to ensure that not a single sign has been left out.

“My key message is that when you pull the camera back, it’s about power and control,” sums up Bill. “These are insidious ways of manipulating someone into a position where you are directing their lives the way you want it.”

In Kristin’s case, the Mitchells later found out that the killer was, in Bill’s words, “a master manipulator,” who had relied on isolating Kristin from family and friends and was jealous of anyone she spent time with, even family. He had huge mood swings, though that was not immediately apparent. He texted and called her incessantly. “He was a real charmer,” says Bill, “but it was a practiced act.”

The message is loud and clear. If it could happen to them, it could happen to anyone. Before Kristin’s murder, like many people, the couple knew nothing about domestic violence.

“We both had the most stereotypical, clichéd version of what domestic violence was,” says Bill. “We didn’t think it happened in nice neighborhoods,” says Michele. “We didn’t know anything about it.”

Now they are authorities. “I realized that we were taught the hard way,” says Bill, who also created a When Dating Hurts website as a resource. “We didn’t have to imagine any of this. You become a subject-matter expert just by definition.”

Beth Sturman, executive director of Laurel House, a domestic violence agency in Norristown, Pennsylvania, says the Mitchells have helped broaden the perception of who can fall prey to domestic violence.

“There’s a lot of stereotypes and public perception on who domestic violence happens to and a perception that it doesn’t happen to people like Kristin, but it does,” says Sturman, who met first met the Mitchells at an awareness run/walk in 2007 called Kristin’s Krusade, and who has since become a close family friend. “A lot of domestic homicides we see are in higher-income, higher-education families. Because Bill is intent on helping to raise awareness, it’s helpful to have a spokesperson who can say, ‘This happened to us’ and audience members can say, ‘Oh, if it can happen to them, this can happen to my kid, too.’”

In addition to the book, this past January, Bill decided to use another platform to continue to spread the word with his When Dating Hurts podcast. For the podcast, he interviews everyone from survivors of domestic violence and their family members to people who run women’s shelters to homicide detectives and other law-enforcement professionals, including Pennsylvania Montgomery County detective Jim McGowan, who was assigned to interview the killer on the day of Kristin’s death. Bill stays in touch with all his guests, he says, because “each and every one of these people become a connection to Kristin.”

On a mid-June day, that connection is Maria Macaluso, executive director of the Women’s Center of Montgomery County. The week before marked the 16th anniversary of Kristin’s death. The day was spent in quiet reflection. At night, the family ate Pasta for the Angels—shrimp with angel hair pasta—Kristin’s favorite dish.

“June 3 is always a test,” writes Bill via email on that day. “I will be glad to see the sun rise tomorrow.”

Sitting at the dining room table with nothing more than his laptop, a mic, a glass of water, and a script, Bill welcomes Macaluso to the podcast, in which he covers topics such as domestic violence statistics, how people get stuck in toxic relationships, and what happens when they can finally get away.

Before Macaluso answers his first question, she says she has something to share. “You are one of the kinds of people who inspire me to do this work,” she says. “To see you transform your pain into something positive is really inspirational.”

“Now I have to speak with a lump in my throat,” says Bill, looking up from his script. “I always feel like I don’t have a choice, but of course I do.”

“I DON’T BELIEVE MY WORK WILL EVER BE DONE. . . . WITHOUT KRISTIN IN OUR LIVES, EVERYTHING ELSE FALLS SHORT.” —BILL MITCHELL

As a result of his smooth and steady voice, perfect diction, insightful questions, and keen listening skills, one might forget that Bill is not a born broadcaster, but a grieving parent. The conversation is compelling and continues for an hour or so, and Bill thanks her for her time.

“My admiration for you and all those working in the domestic violence field is just limitless,” he says to Macaluso. “Every single day you are handling life and death situations and helping innocent members of our community to become educated and stay safe from the insidious menace we know as domestic violence.”

Later, he will edit the audio, then upload it to Apple and line up more subjects for his weekly podcast, whose audience continues to grow.

Clearly, his work has made a difference. To date, he has 13,261 connections on LinkedIn and has sold close to 1,000 copies of When Dating Hurts. His podcast has been downloaded more than 2,000 times—facts and figures he checks almost daily, not out of ego but because every exposure represents another possible person saved.

And he’s seen the impact of his words in real time. One day, after giving a speech about Kristin and domestic violence to Wawa employees in the Philadelphia area years ago, he was approached by an audience member.

“What did you think [of the speech]?” he asked her. “And the woman said, ‘I know what I think. I’m getting a divorce.’ [Apparently], as I went through the warning signs of an unhealthy relationship, she said, ‘yes’ to every single one. That kind of thing happens all the time.”

Sam Gallen, the lead detective assigned to Kristin’s case, is still in touch with the Mitchells. And despite working on a homicide unit for 18 of his 41 years, this story has always stuck with him.

“Seeing how it impacted their lives has always stayed with me,” says Gallen, who has a daughter of his own. “Families want answers and some type of closure, if that’s possible with a murder victim, but once the case is resolved, that’s kind of it. We have seen others trying to move forward and make some positives out of a horrible situation, but not like Bill—he has taken on such a role to try to educate and inform family members of things to look for and, hopefully, save lives.”

Although he recognizes that he has saved many people from, in his words, “the vicious claws of dating violence,” Bill knows that even after 16 years, there is more work to be done.

“There always seems to be a new crop of bad actors rising out of the ground to challenge good people,” he writes via email. “I don’t believe my work will ever be done. I will never be satisfied no matter how many people say we helped them and no matter how many books sell, or podcast episodes are played. Without Kristin in our lives, everything else falls short.”