News & Community

You Are Here: Star Fighters

Tales from Jewish boxers, home brewers, and writer Rafael Alvarez.

Star Fighters

December 11, 2016

Lloyd Street

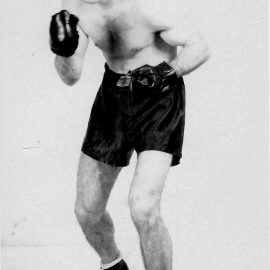

“How many people know who Benny Leonard was?” Mike Silver asks the crowd gathered at the Jewish Museum of Maryland. “Benny Leonard was the most famous Jewish person in America in the 1920s. Not Albert Einstein. Not Justice Louis Brandeis.”

Leonard, explains Silver, author of Stars in the Ring: Jewish Champions in the Golden Age of Boxing, fought his way out of Manhattan’s East Side ghetto to become one of the great boxers of all time during the Roaring ’20s, holding the lightweight title for nearly seven years. “He quit to take care of his sick mother. How Jewish is that?”

In his book, Silver chronicles 29 Jewish world champion boxers and more than 160 contenders from the 1890s-1950s, including a half-dozen Baltimore brawlers—welterweights Jacob “Jack” Portney and Benny Goldstein, flyweight Benny Schwartz, middleweight Sylvan Bass, and lightweights Charley Gomer and Isadore “Izzy” Rainess. Silver also gives a shout-out to legendary trainer Heine Blaustein. “Baltimore was a great fight town,” Silver says.

It wasn’t unusual in those days, Silver continues, for Jewish boxers to change their name. Not because of anti-Semitism, but family (read: mother’s) disapproval of the sport. Leonard was really Leiner, for example. Often, Jewish fighters switched ethnic identities altogether, killing two birds with one stone by trying to appeal to the sport’s huge Irish fan base.

“My uncle was Baltimore welterweight Patsy Lewis—that’s pretty Irish. His real name was Julius Rosenbloom,” volunteers Jerry Russ, 81, who went to the fights with his father at the old Baltimore Coliseum. Carlin’s Park was another popular venue.

At a time when boxing and baseball were the country’s biggest draws, fighting wasn’t just a means to make money for working-class immigrants—a four-round bout could pull in the same pay as a week in a sweatshop—it was also a means of assimilation and pride for Jews.

“Einstein, brilliant scientist, but who understands the theory of relativity? Brandeis, brilliant justice, but how many people read Supreme Court decisions?” Silver asks. “A punch in the nose? That, everybody understands.”

Beer Run

December 3, 2016

North Belnord Avenue

Former University of Maryland, Baltimore County cross country star Eric Shuler won this morning’s 5K through Patterson Park in convincing fashion, posting a time of 16:39—more than two minutes faster than his closest rival. But now the real competition is underway as more than 400 runners quench their thirst in the schoolyard behind Patterson Park Public Charter School. Here, 21 home-brewers are chatting about hops and recipes, pitting their kitchen, basement, and garage-brewed ales against one another while vying for today’s biggest title: Best Homebrew.

The Patterson Park 5K, Fun Run, and Homebrew Tasting—this is the beer-making competition’s third year—supports the school’s effort to send students to Spanish-speaking countries where they can practice the language they’ve been studying.

Most of the beer makers acknowledge their brewing evolved pretty quickly from hobby to near-obsession. “I liked to drink beer, that’s how I got started,” laughs (the aptly named) Stephen Porr, who eventually opened The Grain Bill, a family-run, home-brew supply store in Red Lion, Pennsylvania. “It went downhill from there.”

In the end, Darren Stimpfle, a surgical physician’s assistant by profession, sweeps both the Crowd Favorite and Brewer’s Choice awards with his dry-hopped, golden sour ale with apricot. Stimpfle, who spends eight hours each Friday brewing at home, is developing a business plan to sell his beer commercially. “I’m the runner and he’s the brewer and I support him—I really do,” says his wife, Shannon Gibbons, who took third place in the 5K’s 30-34 age group. “We went to Belgium on vacation and visited the Cantillon Brewery in Brussels three times. Naturally, I wanted to go to Paris and we did,” she adds with wry cheerfulness. “For two days.”

Christmas Stories

December 17, 2016

Eastern Avenue

“The year after my grandmother died I went looking for the spirit of Christmas on Eastern Avenue,” Rafael Alvarez says, reciting the first sentence from his 1999 book, Hometown Boy, at the 10th Annual Highlandtown Literary Extravaganza at the Enoch Pratt Southeast Anchor Library.

“Eastern Avenue,” Alvarez, an occasional contributor to Baltimore, explains, “was where you bought your first communion clothes before the Eastpoint Mall. It was where you shopped for everything.”

Alvarez launched his holiday storytelling, music, deviled egg, and pizelle festival after returning from Hollywood, where he wrote for TV following a stint penning episodes of The Wire. The crowd over the years has been a mix of friends, family, musicians, writers—including Afaa Michael Weaver, a former Procter and Gamble factory worker who has become one of the country’s foremost poets—and Highlandtowners who come to hear “real Baltimore” tales. Before intermission, Alvarez asks audience members to share their own Christmas stories, which mostly yields sagas of sibling rivalry and poor decisions.

David Ettlin, a retired Baltimore Sun editor, jokes his parents never bothered with a Christmas tree during the holidays while he was growing up. “We’re Jewish,” Ettlin deadpans. Determined to get a tree after marrying a Methodist, but not wanting to shell out big bucks, Ettlin hatched a plan with his wife—against the advice of their teenage daughter—to sneak into the woods together and cut down a live pine.

“All of a sudden, there’s a patch of mud and Bonnie does a flip and fractures her wrist horribly,” Ettlin continues. At the emergency room, he learns there will be a $50 copay for the orthopedic surgeon and then an additional $10 for a generic painkiller, or $35 for the brand name. “I feel guilty and go with the brand name,” Ettlin says. “But what I’m thinking is, ‘I’m out $85 and still don’t have a damn tree.’”