History & Politics

Saving Little Italy

The iconic ethnic neighborhood has outlasted all of Baltimore’s old-world enclaves. Now it faces its greatest challenge in more than a century.

By Ron Cassie

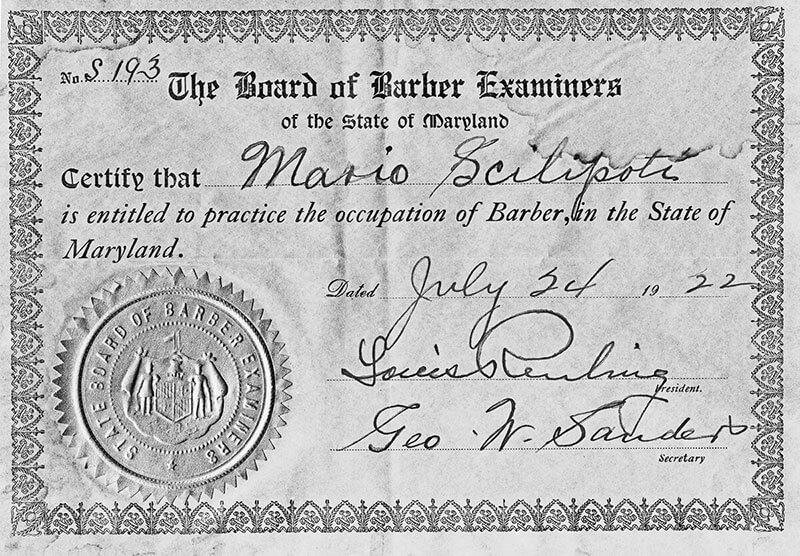

Mario Scilipoti left his newly wed and, unbeknownst to him, pregnant wife behind in their mountainside Sicilian village when he departed for the United

States. The 23-year-old did not speak English. He did not have, or

need, a visa when his ship, the Patria, sailed past the Statue of Liberty

and landed at Ellis Island. He did not have a lucrative job or graduate school

admission waiting. Arriving 100 years ago this spring, he only

had hopes of a brighter future for his soon-to-be-family and an uncle

in Baltimore who was a barber. Following a lengthy apprenticeship

while his still-unmet bambina spoke her first words back in Sicily,

Scilipoti received his own license from the Maryland Board of Barber

Examiners on July 24, 1922. Over time, he built a clientele and opened

a shop on East Pratt Street. After five years, he returned to Sicily to

reunite with his wife, Domenica, and daughter, Josefa, and they later

followed him back to Baltimore.

Mario Scilipoti left his newly wed and, unbeknownst to him, pregnant wife behind in their mountainside Sicilian village when he departed for the United

States. The 23-year-old did not speak English. He did not have, or

need, a visa when his ship, the Patria, sailed past the Statue of Liberty

and landed at Ellis Island. He did not have a lucrative job or graduate school

admission waiting. Arriving 100 years ago this spring, he only

had hopes of a brighter future for his soon-to-be-family and an uncle

in Baltimore who was a barber. Following a lengthy apprenticeship

while his still-unmet bambina spoke her first words back in Sicily,

Scilipoti received his own license from the Maryland Board of Barber

Examiners on July 24, 1922. Over time, he built a clientele and opened

a shop on East Pratt Street. After five years, he returned to Sicily to

reunite with his wife, Domenica, and daughter, Josefa, and they later

followed him back to Baltimore.

Mario Scilipoti’s original barber’s license, July 1922.

In 1930, Tommaso, the couple’s second child, was born above that rowhouse Pratt Street barbershop. He, too, would earn a barber’s license and place a spinning red, white, and blue pole outside the window of his rowhouse. However, the younger Scilipoti, nicknamed “Mazzi” in the neighborhood, also had his eye on another career, which would prove fortuitous for the section of Southeast Baltimore already known by then as Little Italy.

Tom “Mazzi” Scilipoti had been in grade school at nearby St. Leo’s when his father, recognizing his interest in photography, bought him his first Ansco folding camera. By 20, he was shooting for the Baltimore Guide, an ongoing freelance gig that the award-winning, now- 90-year-old photographer held for 66 years, until the community paper shuttered in 2016. Over that time, the son of the immigrant barber took more pictures of the iconic Italian-American enclave in its heyday than any other photographer, capturing everyday life from its kitchens, corner stores, sandlot ballfields, Easter processions, and annual festivals—as well as the communions, graduations, and weddings of generations of immigrant families.

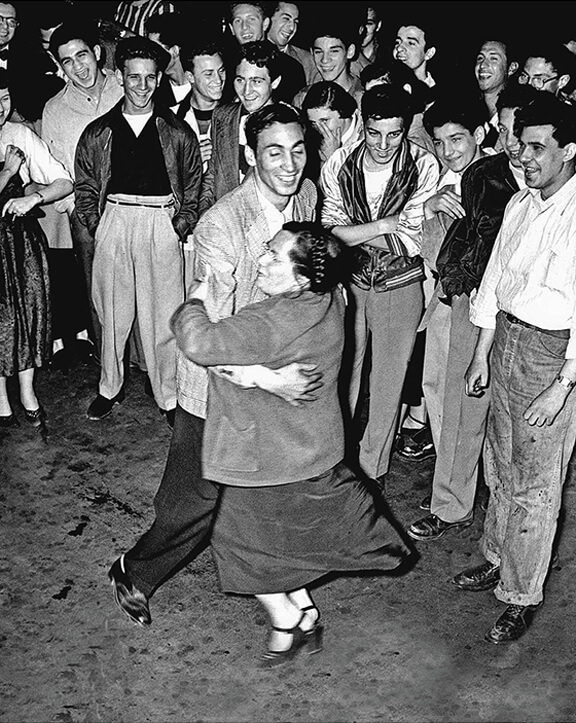

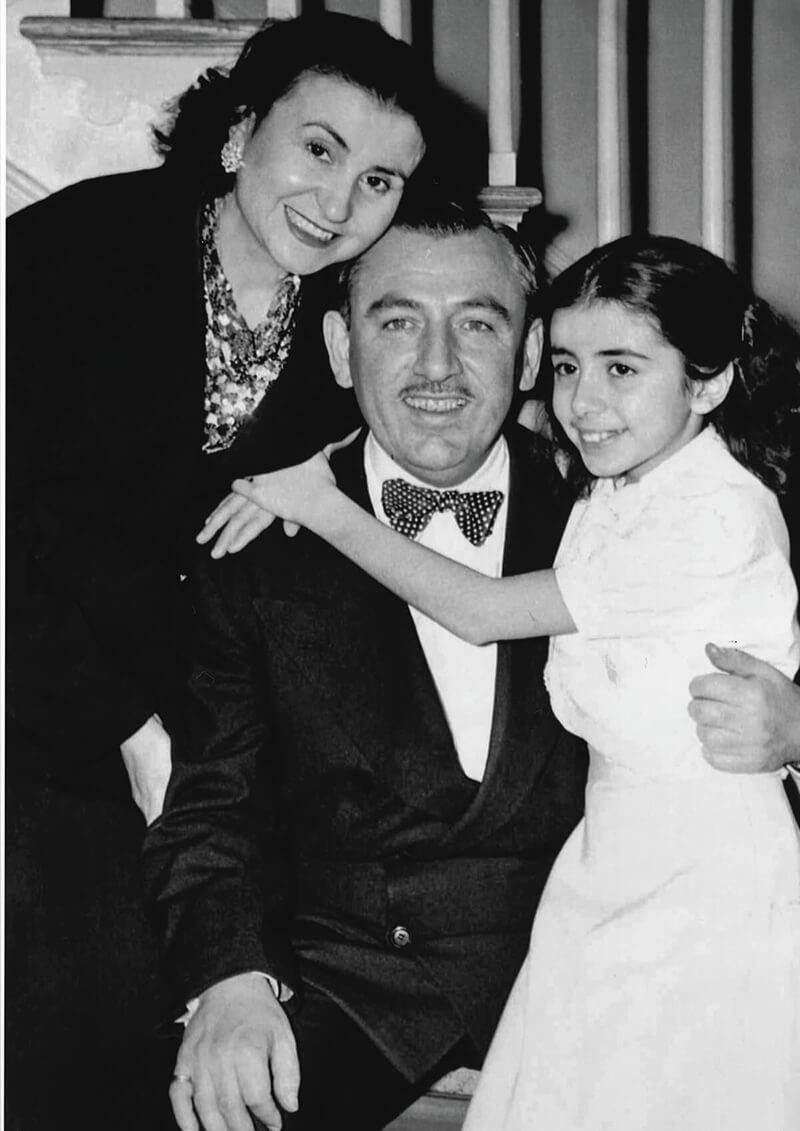

Perry Como meets and greets at Pisa’s restaurant, 1953.

He also documented many of the celebrity visitors to Little Italy’s narrow streets and famed eating establishments, from heavyweight champion Rocky Marciano and the Yankees’ Mickey Mantle and Whitey Ford, to burlesque legend Blaze Starr and pop stars such as Perry Como, to politicians from John F. Kennedy to Bill Clinton.

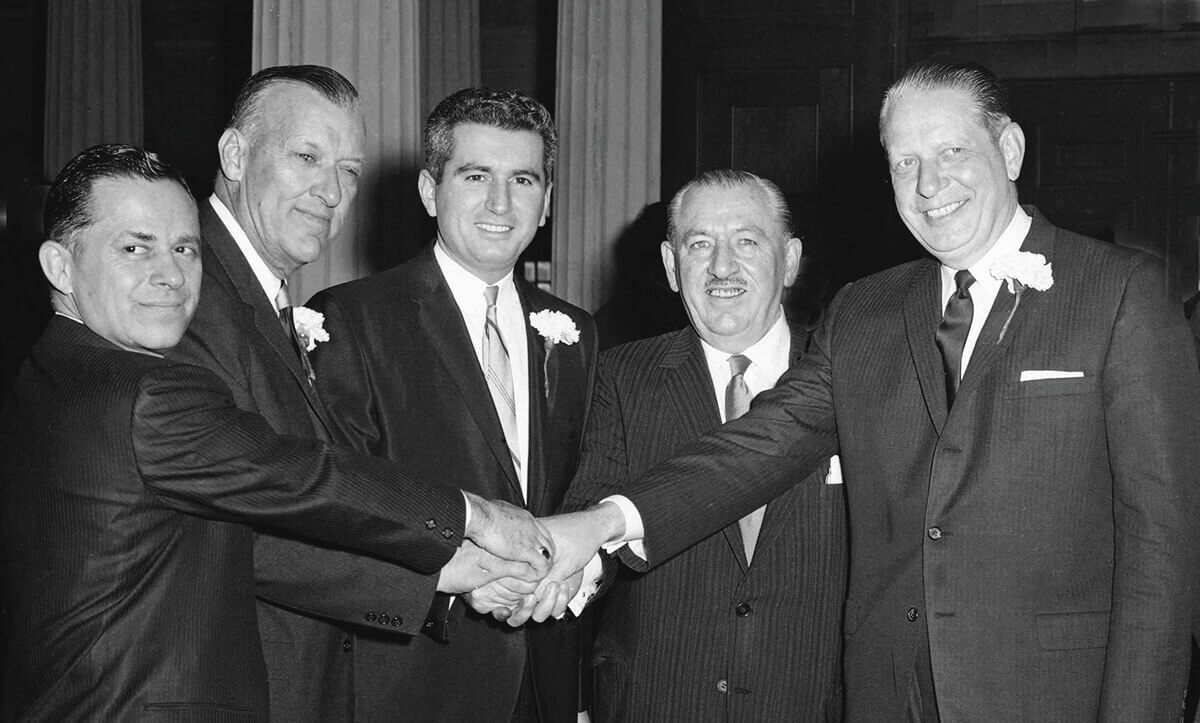

He even served as the official photographer of both childhood pal Tommy D’Alesandro III’s mayoral inauguration and the wedding of Tommy’s daughter, a certain future U.S. Speaker of the House, Nancy née D’Alesandro Pelosi.

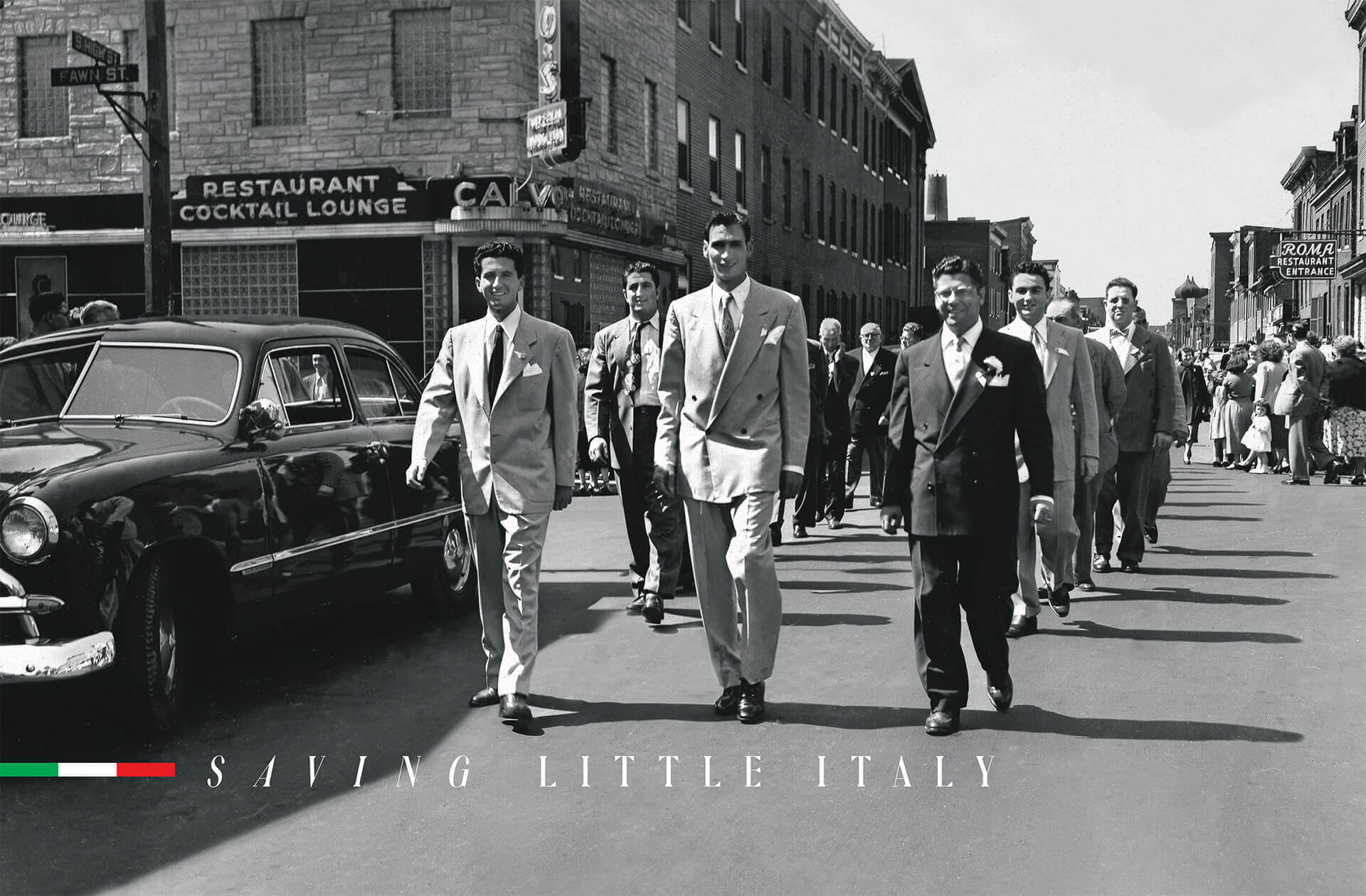

“I’d get a call from Roma’s or Maria’s restaurant, and they’d say, ‘so-and-so just came in,’ and I’d grab my camera and run over,” Scilipoti recalls from his Bank Street home, a few blocks away from the heart of Little Italy. It’s the same rowhouse where he and his deceased wife Concetta, an Italian immigrant, raised their three children and where he has remained for nearly seven decades. “It was an exciting place to be a young photographer,” he continues, with a nod and smile, flipping through some neighborhood photos, which include a 1950s parade led by three young aspirational Little Italy politicians—Tommy D’Alesandro III, John Pica Sr., and Joseph Bertorelli (see opening photo). “It was an exciting place to be an old photographer, too.”

“I’D GET A CALL FROM ROMA’S OR MARIA’S RESTAURANT, AND THEY’D SAY, ‘SO-AND-SO JUST CAME IN,’ AND I’D GRAB MY CAMERA AND RUN OVER.”

Tom “Mazzi” Scilipoti (front, second from left) and

neighborhood boys in front of the old Luge’s Confectionary, which is now Sabatino’s.

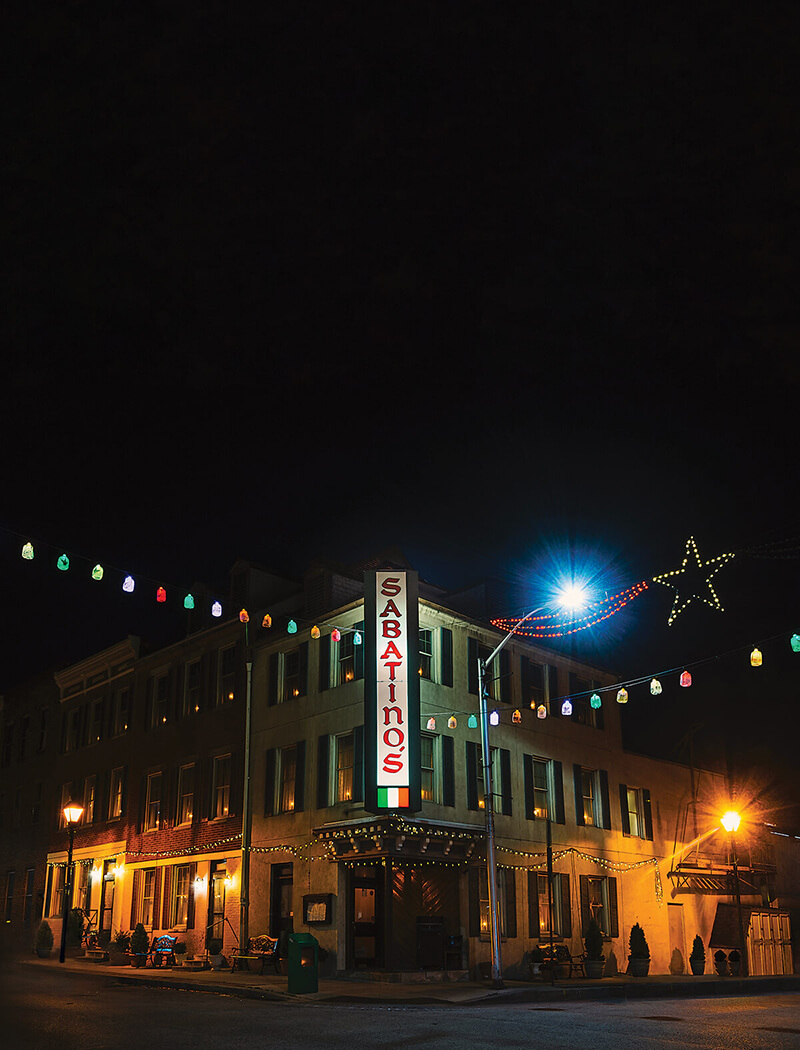

Sabatino's at night. Photography by Jon Bilous

Today, nearly all of Scilipoti’s contemporaries have passed, of course, including D’Alesandro, whose death in 2019 marked the end of an era for the once politically powerful Little Italy voting bloc. Popular across the city, he was known as “Young Tommy” to distinguish him from his father, Tommy D’Alesandro Jr., a former congressman whose election as mayor in 1947 had people dancing in the streets of Little Italy. Meanwhile, many, if not most of Scilipoti’s friends and their descendants moved over the years to Baltimore County for more square feet and larger, grassy backyards. By 1980, assimilation—the very thing Italian immigrants hoped for their children and grandchildren—posed a threat to the Italian haven’s long-term viability. St. Leo’s School, which had educated some five generations of Little Italy kids, was forced to close that year because of the shrinking number of young families in the neighborhood.

“You can’t blame them,” Scilipoti says with a shrug, speaking of those who decamped for the suburbs while he stayed put. “The people who left, they come back for the festivals or to go to Mass at St. Leo’s or to see people they know, anyhow. But it wasn’t for me. My studio was here. The church was here. I had a boat in the marina. It was convenient. It’s still convenient. My son Mario, he lives close by in Highlandtown. I know the restaurants are struggling terribly now, but the restaurants were here, and they’re still here. I’ve got an exhibition up right now at Chiapparelli’s.

“The future of Little Italy?” Scilipoti says, considering the impact of the deadly pandemic on the dozen-plus local eateries, a couple dating back to the 1940s and 1950s, and the broader neighborhood, which has been forced to cancel its annual festivals, events, and activities, and severely limit church attendance. Scilpoti says he’s not too worried—after all, Little Italy has held on to its identity longer than all of Baltimore’s other Old-World enclaves. “All I know is that it’s been here as long as I’ve been here.”

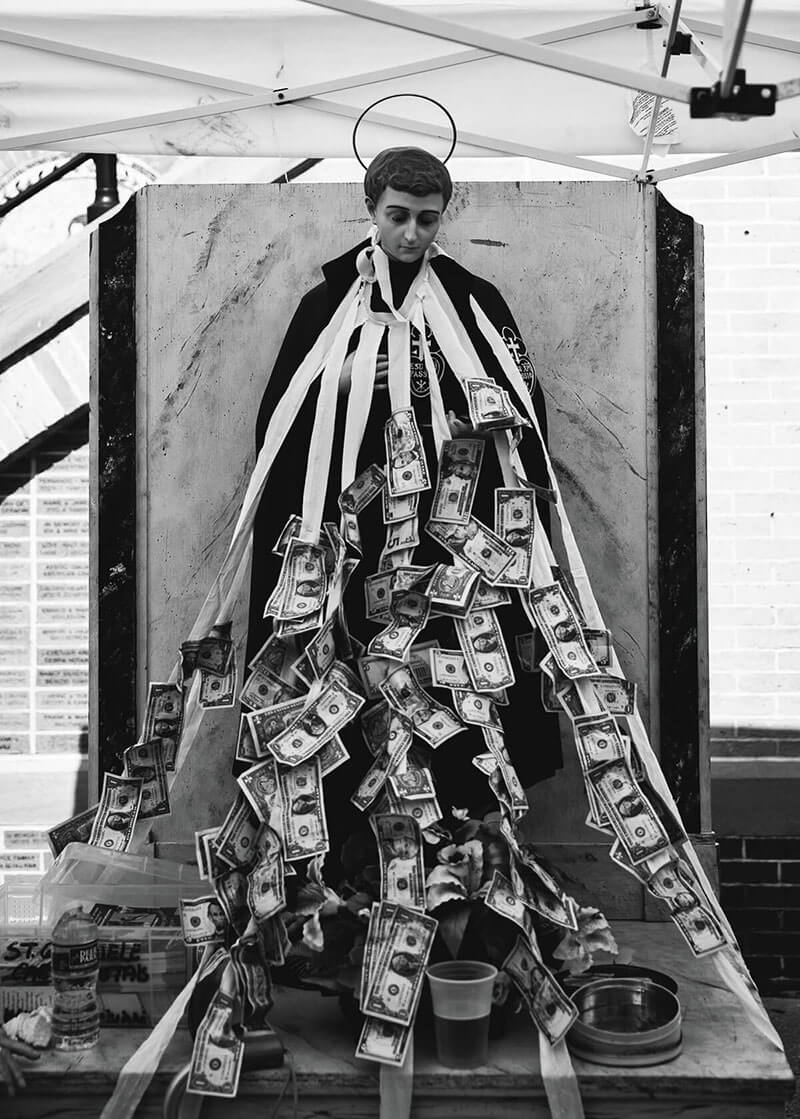

The tight-knit, roughly 15-square-block neighborhood, with its family—owned restaurants, bocce leagues, cabaret, annual festivals (St. Gabriel, St. Anthony, and Madonnari Arts), homespun spaghetti and ravioli fundraising dinners, culinary and language classes, and church listed on the National Registry of Historic Places—in other words, the Little Italy we know today—was in many ways born out of the first crisis it weathered. In 1904, the Great Baltimore Fire swept across the city, leveling downtown over a day and a half before it threatened to cross the Jones Falls and reach what was then referred to as the Italian “colony.” At St. Leo’s, the devout offered prayers that their homes and church be spared. As the flames continued to move closer, they cried out to St. Anthony of Padua, one of Italy’s most beloved saints, pleading for intercession. Eventually, terrified residents watching from the banks of the Jones Falls raced back to St. Leo’s, where they removed the statue of St. Anthony and carried it to the harbor for its protection, promising to honor the saint with an annual feast if the neighborhood survived, which it did because of a sudden, some said miraculous, early morning shift in the winds.

Soon after, The Baltimore Sun began noting and covering the community’s new St. Anthony festival, now describing the neighborhood no longer as a “colony” or “settlement,” but more affectionately as Little Italy. “The night scenes along the streets of Little Italy are as if they were transported from the streets of Naples or Genoa,” The Sun wrote in the summer of 1911, highlighting the neighborhood’s talented accordion players, as well as the immigrant laborers’ love of good wine, spaghetti and tomato sauce, imported sardines, and Italian soups and stews. “True, there are American trolley cars, the [row] houses are of the American architecture . . .the streets are paved with Baltimore cobbles. But the language is the language of Italy, the pleasure of the people of those of Italy and, by stretching the imagination, one might think he were in the land of King Victor Emmanuel.”

“TRUE, THERE ARE AMERICAN TROLLEY CARS, THE [ROW]HOUSES ARE OF THE AMERICAN ARCHITECTURE . . . THE STREETS ARE PAVED WITH BALTIMORE COBBLES. BUT THE LANGUAGE IS THE LANGUAGE OF ITALY. . . AND, BY STRETCHING THE IMAGINATION, ONE MIGHT THINK HE WERE IN THE LAND OF KING VICTOR EMMANUEL.”

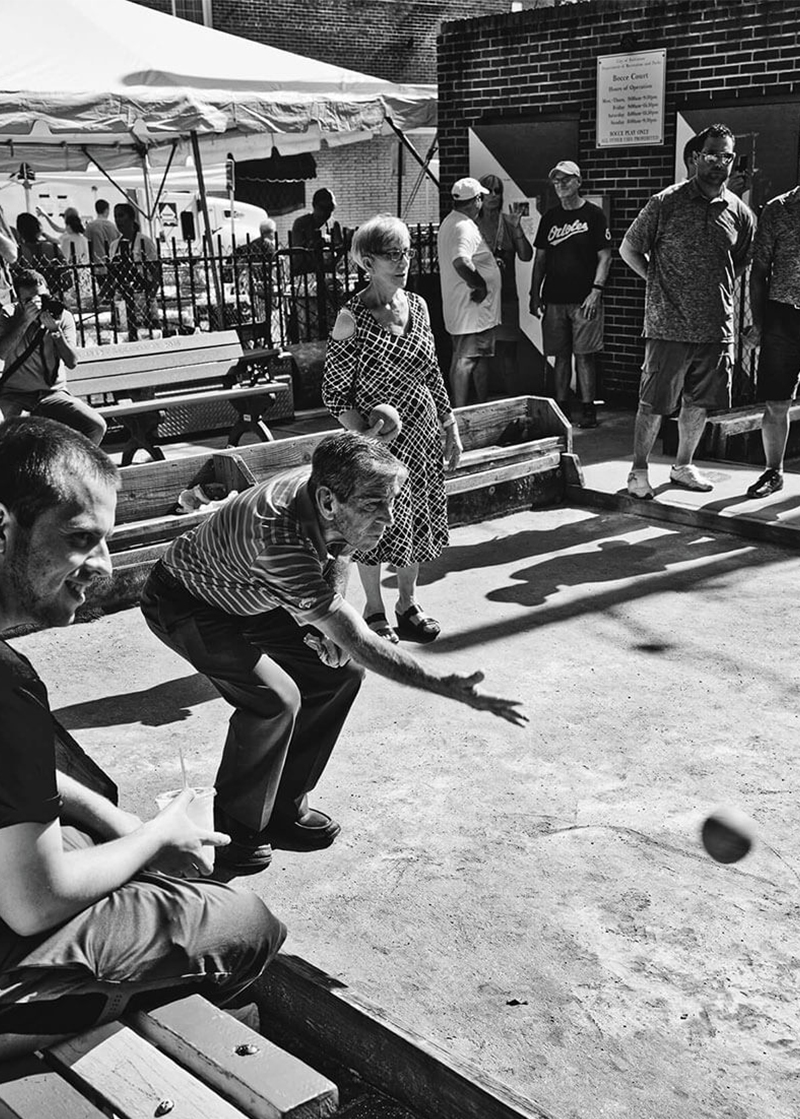

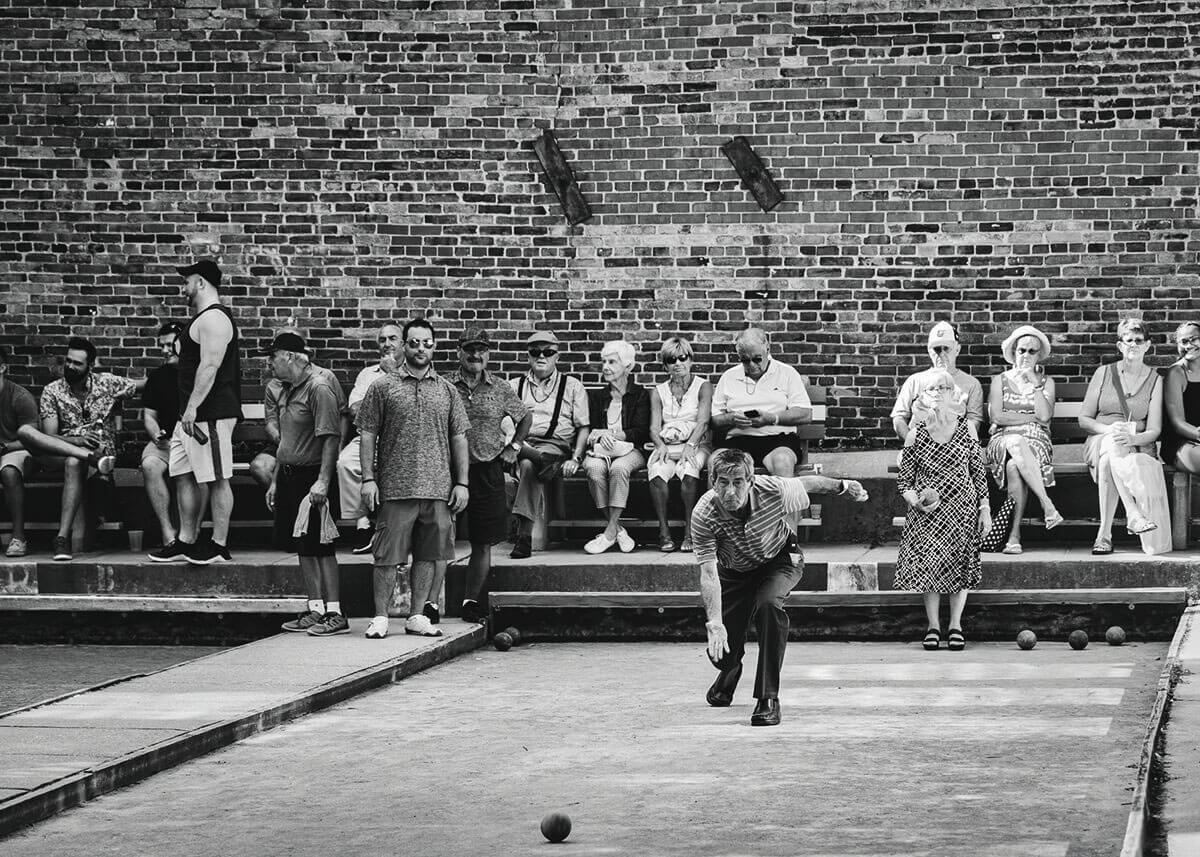

Bocce and pinning dollar bill donations to St. Anthony are among the St. Gabriel Festival traditions (August 2017). Photography by Richard M. Hatch

Over the past 50 years, Little Italy’s imminent death has been greatly exaggerated many times. But there has been no threat akin to the deadly COVID-19 pandemic, with its suddenness, stay-at-home orders, and public closures, except the deadly 1918 flu pandemic. It is worth pointing out, however, Little Italy survived that, too. One way or another, the neighborhood has rolled with every punch, ever since its mid-century heyday. First, it was beckoning suburbs, school desegregation and white flight, and plans for an East-West expressway that would’ve destroyed the harbor neighborhoods. Then came the 1968 riots, which shuttered businesses in East and West Baltimore and hastened the departure of more city residents. By the 1970s, sharp declines in church and Catholic school attendance, not just in Baltimore, but across the country, presented existential challenges to the fabric of the neighborhood and, finally, cracks in the community’s stronghold did emerge. The looming aforementioned shuttering of St. Leo’s school, in particular, was widely predicted as Little Italy’s death knell. In 2007, the removal from ministry of Fr. Michael Salerno, the parish’s beloved “Father Mike,” accused of molesting a boy when he was a brother at a New York church in 1970s, proved another punch to the gut for many people in Little Italy.

Neighborhood kids during a May processsion at St. Leo's.

Still, the neighborhood and St. Leo’s persisted.

In fact, Little Italy not only withstood all those blows, it has always rebounded. Sometimes from just faith and good luck. At other times, by the dint of its own stubbornness and creativity. The same year that St. Leo’s school closed, the Inner Harbor opened and gave birth to the city’s tourism industry. The established Little Italy restaurants got a huge shot in the arm, while new ones opened in the mid-1980s, including Dalesio’s and the swanky Da Mimmo, attracting the likes of Tony Bennett, David Bowie, Faye Dunaway, Luciano Pavarotti, Stevie Wonder, Dustin Hoffman, Danny DeVito, Sylvester Stallone, Tom Selleck, and Johnny Depp at a time when Baltimore became a go-to set piece for mainstream Hollywood movies. (Named after original owner Domenico “Mimmo” Cricchio, who died in 2003, that restaurant, long an anchor, closed in January as owner Mary Ann Cricchio announced she was launching Da Mimmo Tours of Italy.)

Similarly, the opening of Camden Yards in the mid-’90s provided another major boost. The acclaimed, retro-style ballpark brought new legions from Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Washington—every city with a Major League club, really—to the neighborhood all summer long as new restaurants opened up again.

Night shot of Roma and gaslight streetlamp near

High and Fawn streets, 1957.

In terms of its own initiatives, the neighborhood’s bocce courts, refurbished last year with help from the Department of Recreation & Parks, were built in 1993. They have been well-used ever since, with leagues, pre-coronavirus, run several nights a week by Giovanna Blatterman, a Sicilian immigrant whose daughter Gia Fracassetti and son-in-law chef Gianfranco Fracassetti, own Gia’s Café. The neighborhood’s annual film festival, which was the first of its kind in Baltimore when it began in 1999, drew international attention to Little Italy. (However, that has been on hiatus for the past three years and doesn’t seem likely to return any time soon with the purchase of the parking lot that previously hosted the summer movie nights.) In 2008, Germano Piattini co-owners Cyd Wolf and Germano Fabiani brought live music to the neighborhood with a regular cabaret, on hold as well. They also founded the annual three-day Madonnari Arts Festival in 2015 and are making plans to bring that back next September after being forced to cancel this fall.

And three years ago, Joe Gardella, owner of Joe Benny’s, which introduced Sicilian-style focaccia pizza to the neighborhood, created an annual “best meatball” contest. Not surprisingly, it sells out the Little Italy Lodge.

Meanwhile, while many of the older restaurants here—like Sabatino’s, Chiapparelli’s, Dalesio’s, and La Scala—emphasize traditional Italian-American fare, others, such as Germano’s, Aldo’s Ristorante Italiano, and La Tavola, have added modern twists.

A wedding at St. Leo's.

Still, Ray Alcaraz, who co-founded the Promotion Center for Little Italy, Baltimore and whose parents reside in the same Little Italy rowhouse where he was raised, says it is the presence of St. Leo’s, the beating heart of the community since 1881, that has been the key to the neighborhood’s longevity. Even though the treasured church no longer packs every pew each Sunday, about 300 parishioners attended weekend services before the pandemic. During the ongoing COVID-19 crisis, that number has dwindled to just two dozen or so at each of the church’s three Saturday and Sunday Masses, so St. Leo’s has been forced to provide online services to maintain contact with its parishioners. “The staying power of the neighborhood, with and without the school, which I attended, has primarily been St. Leo’s,” says Alcaraz, an usher at the church for 30 years now. “Everything changes around it, including the restaurants, but the St. Anthony and St. Gabriel festivals, the spaghetti and ravioli dinners, those things, all these years—the connection has been St. Leo’s.”

With nine years spent in Rome, the avuncular Fr. Bernie Carman, clearly the right pastor for St. Leo’s, maintains the tradition of Italian masses at the church. The first full weekend of every month, the first reading and hymns are read and sung in Italian. “We only have a handful of parishioners, mostly the older women, who still speak Italian,” he says, “but it’s important to remember the generations that came before and built this church. It’s one way we recognize the history of the church, and keep the spirit of this community alive, which means everything here.”

St. Gabriel procession

All that said, even before the coronavirus brought Little Italy, like the rest of the city, to a standstill, the past five years have been some of the most challenging in recent memory. One of the unfortunate consequences of 2015 Baltimore Uprising after the death of Freddie Gray, according to restaurant owners, was that it pushed away both regular county and potential out-of-town visitors. At the same time, Orioles’ attendance has been way down—some speculate because of the 2015 Uprising, but the team has also been terrible of late—which subsequently affects downtown hotels and restaurants. One more recent challenge: For a good decade-plus, Little Italy’s traditional red sauce dining culture has faced growing competition from trendier eateries that are part of an increasingly diffuse and diverse restaurant scene, which has garnered national renown. The development of Harbor East has been something of a mixed blessing. Its hotels, condominiums, and high—rise office complexes bring new customers, but it’s also become a commercial and restaurant destination in its own right.

Meanwhile, recent controversies around squeegee kids on President Street and the tearing down of the Christopher Columbus statue at the Inner Harbor have generated unwanted publicity. Nonetheless, all of those things combined pale in comparison to the current peril that the ongoing coronavirus pandemic presents. It has forced not only the cancellation of nearly every neighborhood event, but Lew Gambino’s, formely Ciao Bello, which had been around for decades and recently rebranded with the help of former Raven Ray Lewis, was forced to close permanently. The wine and light fare-serving Osteria da Amadeo said at one point that it was closing permanently, and then recanted. Many, like Joe Benny's, which has opened a carry-out “meatball window” have had to severely curtail operating hours.

“IN SOME SENSE, LITTLE ITALY, WAS [ALREADY] FACING AN IDENTITY CRISIS, BUT THE PANDEMIC MAKES IT AN EXISTENTIAL CRISIS. . .THIS IS OUR GREAT DEPRESSION.”

Present day, Cafe Gia

Ristorante on High Street, which added an outdoor dining space this year. Photography by Gregory McKay

It has also had a devastating impact on the remaining eateries. Aldo’s and Germano’s have closed temporarily almost since the start of the pandemic, but do plan to return. Others, such as Isabella’s, Vaccaro's Italian Pastry Shop, Casa di Pasta, and the newer Little Italy additions—Angeli’s Pizzeria and Ovenbird Bakery, which opened during the pandemic—transitioned more easily to a carryout-oriented operation. Amicci’s, already a less formal dining experience than some of the older establishments, blends its limited indoor capacity with outdoor seating and a carryout menu, but revenue there remains way down.

Sabatino’s added sidewalk tables as well and also created a delivery program, “Sab’s in the Suburbs,” that targets different county areas—Parkville, Towson, Ellicott City, etc.— on different days of the month. The mammoth restaurant, which for decades was open until 4 a.m. while catering to the late-night bar crowd and hospitality industry staffs, seats more than 400 people. But it has struggled to fill a quarter of its tables, which would be allowable by law, in large part because of health fears by its generally older clientele. “We are one of the restaurants that still has a regular customer base that comes once or twice a month and has been coming for decades, mostly folks that live in the county,” says Vince Culotta, co-owner of Sabatino’s, which was founded in 1955 by his uncle, Joseph Canzani, and Sabatino Luperini, both Italian immigrants. “But once people establish new habits, it’s hard to bring them back. That’s why we are going to them.”

Gia’s constructed a cozy sidewalk table dining area to help limit coronavirus exposure for its guests. But the general fear is what happens as temperatures plummet and the coronavirus’ second wave spike continues this winter.

“We are at an inflection point in Little Italy,” says Sergio Vitale, who opened the acclaimed Aldo’s Ristorante Italiano in 1998. “In some sense, Little Italy, irrespective of the pandemic, was facing an identity crisis, but the pandemic makes it an existential crisis. Our business is down 85 percent. This is our Great Depression.

“The apprehension, the mood,” Vitale adds, “hasn’t been matched since the Great Fire in Baltimore, when everyone in Little Italy banded together and prayed that the fire would stop.”

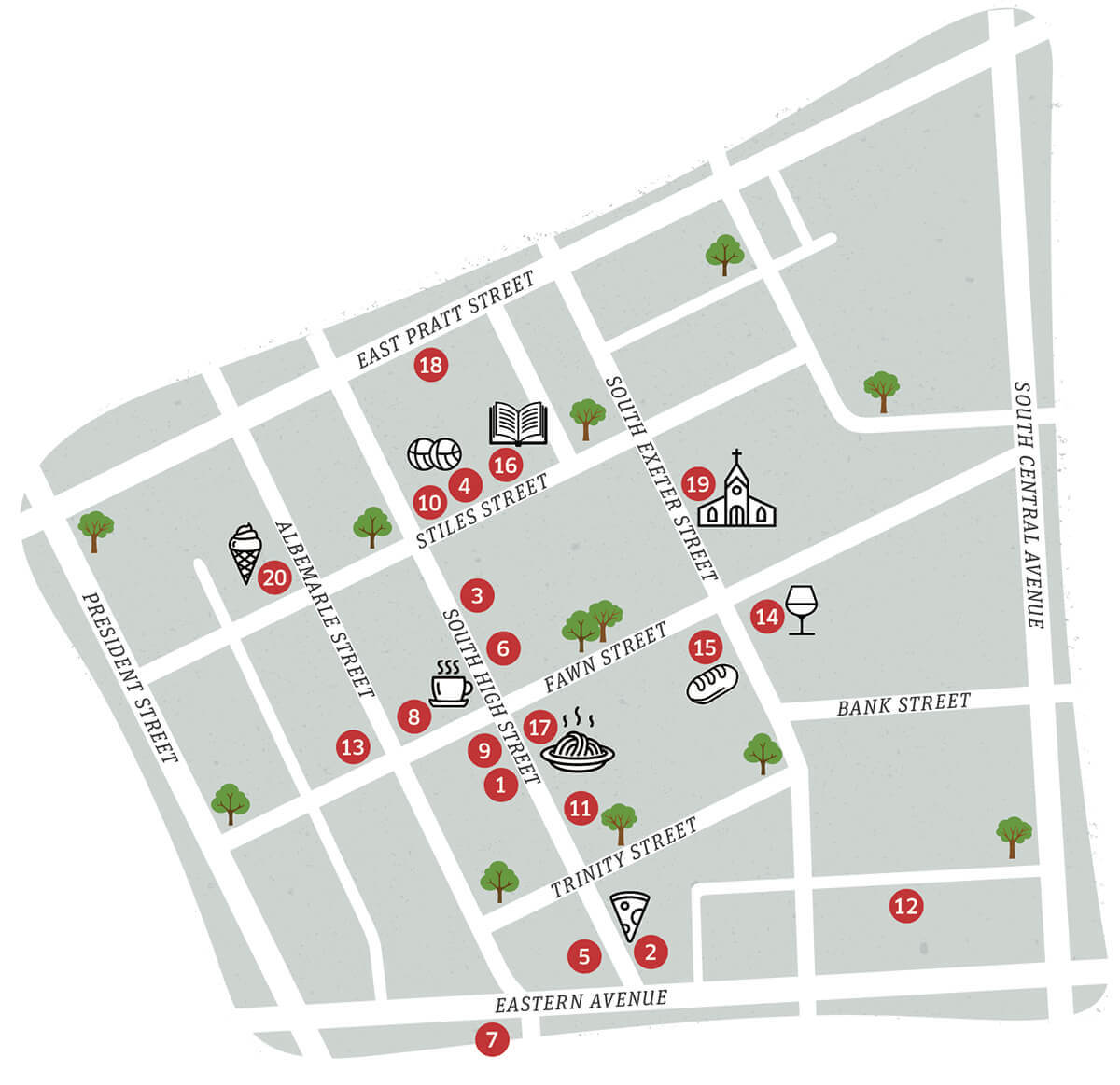

LITTLE ITALY MAP

AS LITTLE ITALY ENCLAVES IN CITIES AROUND THE COUNTRY, INCLUDING THE MOTHER OF ALL LITTLE ITALIES IN NEW YORK’S LOWER MANHATTAN, HAVE SHRUNK OR WITHERED COMPLETELY, BALTIMORE’S LITTLE ITALY REMAINS ROUGHLY THE SAME SIZE AS THE EARLY 1900S.

Map by Curt Iseli

Map Legend

- ALDO’S RISTORANTE ITALIANO

- ANGELI’S PIZZERIA

- AMICCI’S OF LITTLE ITALY

- BOCCE COURTS

- CAFÉ GIA RISTORANTE

- CHIAPPARELLI’S

- DALESIO’S OF LITTLE ITALY

- D’ALESANDRO HOUSE / YOSSITA’S COFFEE

- GERMANO’S PIATTINI

- ISABELLA’S BRICK OVEN PIZZA

- JOE BENNY’S

- LA SCALA RISTORANTE ITALIANO

- LA TAVOLA

- OSTERIA DA AMEDEO

- OVENBIRD BAKERY

- PANDOLA LEARNING CENTER

- SABATINO’S

- ORDER SONS AND DAUGHTERS OF ITALY LODGE

- ST. LEO THE GREAT ROMAN CATHOLIC CHURCH

- VACCARO’S ITALIAN PASTRY SHOP

Italian immigrants first began coming to Baltimore in significant numbers shortly after the Civil War. Between around 1880 and 1924, more than four million Italians immigrated to the United States, half of them between 1900 and 1910 alone—the majority fleeing grinding rural poverty, epidemics, earthquakes, and tensions between the new government and workers in Southern Italy and Sicily. Today, Americans of Italian ancestry are the nation’s sixth-largest ethnic group, behind German, Black, Irish, Mexican, and English Americans. For the most part, like Mario Scilipoti, Italians entered the country in New York City, initially at Castle Garden, America’s first immigration center, which opened in 1855, and then at Ellis Island, which received roughly 12 million immigrants between 1892 and 1924. Baltimore’s Locust Point immigration pier, built in 1867 by the B&O Railroad and the North German Lloyd Shipping Company, received more than 1.2 million immigrants between 1868 and 1914, making the city the third-largest port of entry in the U.S. at the time (after New York and Boston). But most of those immigrants, the minority of whom actually remained in Baltimore, came from Germany, and then from Eastern Europe. That group included many Russian Jews, who first settled in and around Little Italy and Jonestown, and Polish Catholics, who worked in and filled the rowhouses of Fells Point and Canton—Sen. Barbara Mikulski’s corner bakery-owning grandparents among them. (One more recent shock to Little Italy families of a certain period was the permanent closing this summer of the all-girls, 173-year-old Institute of Notre Dame high school in East Baltimore, which incredibly produced both Mikulski, the longest-serving woman senator in U.S. history, and Nancy Pelosi, the first woman to serve as Speaker of the House.)

Nancy Pelosi with her father, Mayor Thomas D’Alesandro Jr., and mother, Anunciata “Nancy” D’Alesandro.

Many of the first wave of Italian immigrants who came to reside in Baltimore are said to have gotten here by chance, planning to pass through Baltimore on their way from New York to the burgeoning Midwest. But disembarking at the President Street train station across from what would become Little Italy (and near, coincidentally, the site of some of the first bloodshed of the American war), they found available boarding houses and a familiar, if still budding, Italian culture and associated cooking, and decided Baltimore looked pretty welcoming. Either way, most did not stray far. These immigrants were mostly peasants who took backbreaking work digging ditches and building rail lines, which is not say the era should be romanticized. Partly how the new immigrants got by—and got exploited—was through a complex turn-of-the-century contract labor network known as the “padrone system” (padrone means “boss” in Italian), which helped American rail, mining, and agricultural businesses meet their needs for cheap workers. The Italian middlemen in these networks, the “padroni,” typically took high fees from workers in exchange for jobs, and some served as landlords as well. Child labor among immigrants was common, too, with even small children working in factories and on farms. The first World War, which interrupted the flow of immigrants, finally contributed to the end of the padrone system.

“[Italian immigrants] were lured initially to America with one incentive: they were told that this magnificent country would offer a better way of life for the family,” wrote Suzanna Rosa Molino, the founder of the Promotion Center for Little Italy, Baltimore, in her book, Baltimore’s Little Italy. “Men usually arrived first. They sweated and labored and pinched pennies, and with limited capacity to speak English, they accepted any job, no matter the stench, danger, or task.” Many came intending to send for their families after they had gained a foothold in Baltimore. For others, coming to the U.S. was not necessarily a permanent decision. Many expected to return to Italy after a few years of work and saving. “[My grandfather] was very excited because he heard so much about America,” Little Italy native Ida Cipolloni Esposito told the Baltimore Neighborhood Heritage Project in a 1979 oral history. “But he decided just to come over so that he could add an addition of one room to his home in Abruzzi. And he stayed here for about three years and went back. Then he decided, ‘Italy is not for me anymore. I’m going back to America.’ It was easier living, he said. He brought his son with him.”

By the early 1900s, craftsmen—carpenters, bricklayers, and stonemasons—arrived from Sicily and the Italian “boot” regions of Abruzzo, Campania, and Calabria. These laborers and artisans sought out the nearest Roman Catholic church. At that time, it was St. Vincent de Paul on North Front Street, which by 1874 had begun hosting Mass in Italian in its basement. St. Leo’s Church, just blocks away, was established in 1881, specifically for the influx of Italians. But at first it also served the Irish Catholics in a neighborhood that was then a quintessential melting pot of German, Irish, Jewish, Lithuanian, and Czech immigrants. By the 1920s, the Italians had displaced every other group as they moved from the neighborhood’s tiny rowhouses to bigger digs. In fact, Lombard Street, one of city’s older downtown streets and once known as the center of immigrant Jewish life—home of famed Corned Beef Row and 106-year-old Attman’s Deli—takes its name from the small Italian town of Guardia Lombardi outside Naples.

Present day Little Italy, site of Rocco’s

Cappriccio on Fawn Street, which closed permanently in 2013 along with some

other prominent area

restaurants. Photography by Gregory McKay

The story of “modern” Little Italy begins in the post-World War II boom. (One of the more remarkable World War II stories related to Little Italy is the number of Italian POWs, estimated at more than two dozen, who were allowed local visitors while held captive at Fort Meade and then stayed in Baltimore and married Italian-American women.) In those days, Little Italy seemingly had at least two of everything—butcher shops, bakeries, hairdressers, barbers, luncheonettes, pharmacies, corner stores, tailors—plus the school, church, Della Noce funeral home, a repair garage, and all the family-owned restaurants.

As had been the case since the days of the organ grinders of Little Italy’s Slemmers Alley, daily life took place in the streets. Arabbers came through with horse-drawn wagons selling fruits and vegetables, and street life was particularly vital on the corners in front of Luge’s Confectionary, now the site of Sabatino’s, and Mugavero’s Confectionary, now the site of the Ovenbird Bakery. Mugavero’s was owned by one Marion “Mugs” Mugavero, a World War II veteran and larger-than-life figure to neighborhood boys in the 1950s and 1960s. Mugs was known for his meatball sandwiches, the phone booth in his store, from which he did his bookmaking (one of many in the neighborhood, by all accounts), and for a tough exterior that belied a gentle heart. He was a man who somehow managed to run a popular corner store, an illegal gambling operation, and keep an eye on local teenagers making sure no one got into “real” trouble. “How do you explain the street corners in Little Italy had requirements?” says Ray Alcaraz, trying to convey the spirit of neighborhood in the mid-20th century. “You had to meet those requirements to hang on a particular corner or earn your way. How do you explain bookmakers and numbers runners? What can be said about living in a multiple generational house or a tenement? Or having an ‘aunt’ on every block? How about the looks you get when you tell [people] how you shoveled horse manure into buckets after the arabbers [had] passed through so your grandfather could use it to fertilize his fig trees and grapevine?”

Baltimore never had the Italian crime mobs of New York or Philadelphia. But if there’s any doubt about the scale of the throwback gambling operations in Little Italy, consider the story behind Sabatino’s famed Bookmaker Salad. “Our maître de Al Isella invented it and named it after his friends, who were regular lunch customers, but had been coming in less frequently because they were getting older and didn’t want a big meal anymore,” says Vince Culotta. “Al went into the kitchen and put seasoned shrimp, salami, provolone cheese, a hardboiled egg, and some olives, red onions, and tomatoes on one of the house salads and named it The Bookmaker’s. He told my uncle, ‘They’ll love that.’” Isella spoke from experience. He once estimated he’d been arrested for gambling more than 50 times, which did not prevent him from serving as a 26th Ward precinct captain. It was like that. If you wanted a job, the guys from the neighborhood recall, you went and saw Anunciata “Nancy” D’Alesandro—not Nancy Pelosi, but her mother, the wife of the mayor. She’d ask if you were registered to vote, and once confirmed, assist you in finding work. (“I think about if she were born today, what she would’ve accomplished,” Nancy Pelosi told Maryland Public Television in 2013.)

“We didn’t have organized crime, we had ‘disorganized crime,’” jokes Ed Mattson, a former Baltimore city cop of Italian descent. He’s describing this on a warm fall day alongside the Little Italy ROMEO crew—Retired Old Men Eating Out—as they reminisce over pasta, eggplant, and Chianti at DiPasquale’s in Highlandtown. That area just north of Eastern Avenue and around Our Lady of Pompei, founded in 1923, is another, later Italian enclave. ROMEO regular Bill Bertazon, who grew up in Little Italy and is also a former city police officer, is there, too. He worked as a teenager at Mugavero’s Confectionary, as did fellow ROMEO Richard Di Seta. “A true education,” Bertazon recalls with a laugh. Inevitably, their conversation turns to what it was like growing up—running errands for bookies, collecting pennies for an afternoon playing the arcades on The Block, learning to smoke cigarettes, laying bricks in the summer between school for someone’s father’s contracting company, and playing baseball on the diamond squeezed in-between the city morgue, pumping station, and rail tracks down at the end of President Street. Baseball talk also leads to memories of Cosimo “Toodie” Geppi and his legendary fastball. “Toodie was twice as big as the rest of us and threw twice as hard as anyone,” says Di Seta of the beloved deceased older brother of this magazine’s publisher. “It was brutal to try to hit him, and he was wild, too. He had you shaking in your shoes.”

“INEVITABLY, THEIR CONVERSATION TURNS TO WHAT IT WAS LIKE GROWING UP. . . PLAYING BASEBALL ON THE DIAMOND SQUEEZED INBETWEEN THE CITY MORGUE, PUMPING STATION, AND RAIL TRACKS. . .”

The first

Little Italy Little

League included

Cubs, Yankees,

Cardinals, and White

Sox teams, 1957.

It’s undeniable that people like to reminisce about the “good old days” of Little Italy. Scott Panian, who opened Amicci’s in 1991, notes how much has changed in just the past five years. As he stares out his front window, he can’t help but see that Ciao Bella’s, Rocco’s, Caesar’s Den, and Da Mimmo have all closed around him. “When I came down here, there were 22 restaurants, and High Street was gridlocked every night.” The demographic base of his restaurant has also changed. For 25 years, he says, his typical customers were 40-year-old couples who had moved to the county and stuck with them. That changed in the aftermath of the Baltimore Uprising, he says, and in the long run, may be a blessing in disguise. His client base and staff have gotten more diverse, better reflecting the city today, and perhaps indicating a way forward for the restaurants and neighborhood in post-pandemic Baltimore—whenever that is.

“We had to pivot to get those 20 to 40-year-olds who are picking up chicken parms on the way home from work,” Panian says. “Little Italy was very provincial. Our clientele has gotten way more diverse since 2015, and our staff has gotten way more diverse, too. We’ve redecorated and tried to make it more of a Baltimore city neighborhood restaurant as opposed to old-school Italian. During the pandemic, I’m staring at my bar not being open, and I’m like, ‘We have to paint this place.’ Instead of rehanging the old Italian movie posters, I put out a call on social media for local art, and we’ve been overwhelmed with the response. Since March, my dining room has been filled with local art.”

In an effort with similar echoes, Cyd Wolf of Germano’s says she and her husband are moving forward with plans for an art gallery in Slemmers Alley. They also plan to remake the restaurant, adding an Italian market. “There needs to be more retail businesses,” Wolf says. “We need other types of businesses that will bring people into the neighborhood.”

Panian stresses Little Italy restaurants have to look inward and embrace the diversity of the city. “The people [who live and work] within 20 blocks of me are going to build my business back up. You’re doing yourself a disservice when you live in a city that’s 65 percent minority and not reaching out to those customers. If you look around this neighborhood now, there’s less Italian ladies with housecoats and there’s more 30-year-old couples. I’ve got to get those people in here. I’m not getting those people back from Timonium.”

Little Italy native Rosalia Scalia, author of the forthcoming short story collection Stumbling Toward Grace, believes the sentiment about restaurants needing to appeal to a broader cross section of the city applies to the rest of the neighborhood as well. At the Rev. Oreste Pandola Adult Learning Center, in the former St. Leo’s School, that’s already happening, with culinary and language classes that bring folks in from other neighborhoods. The cozy Little India restaurant remains open, and a Black-owned sports bar and restaurant, featuring an international menu, is planned for the old Vellegia’s site.

After the Columbus statue was toppled, Scalia penned an op-ed to The Sun, stating her opinion that he was not the best representative of Italian Americans. Instead, she suggested Italian Americans could honor Mother Cabrini, the Italian-born founder of Missionaries of the Sacred Heart of Jesus and the first U.S. citizen to be canonized for her decades of service to Italian immigrants. Contrary perhaps to common stereotypes, she says she received more notes in support of her position from the neighborhood than against.

Bill Martin, a past president of the Associated Italian Charities of Maryland, says the statue is being remade, but will be placed elsewhere. He also said he’d like the Columbus memorial replaced by a statue of an immigrant Italian family, an idea that no doubt would resonate in many parts of Southeast Baltimore, which continues to see its Mexican and Central American immigrant population grow and open new businesses.

“It’s harder to attract some of the younger people, whose sensibility about Columbus, and the Catholic Church, is different today,” says Scalia, adding quickly that she loves “Father Bernie” and invited him over to bless her rowhouse after her recent renovations.

In other ways, she continues, the beauty and simplicity of living in Little Italy, as walkable a neighborhood as there is in the city, remains as compelling as ever.

“I moved out of my parents’ house when I was 19 because I thought it was too confining. Everyone knew each other’s business,” she says. “I got married, moved to Owings Mills, and got pregnant. When I knew my marriage wasn’t going to work out, I moved back, because I knew I would need support, and it was here waiting for me. That was 41 years ago. I haven't left since.”

Scalia’s mother, Philomena, 92, and her mother’s sister, Eleanor, 88, still live here, too. Next door to each other, of course.