COVID-19

On The Front Lines

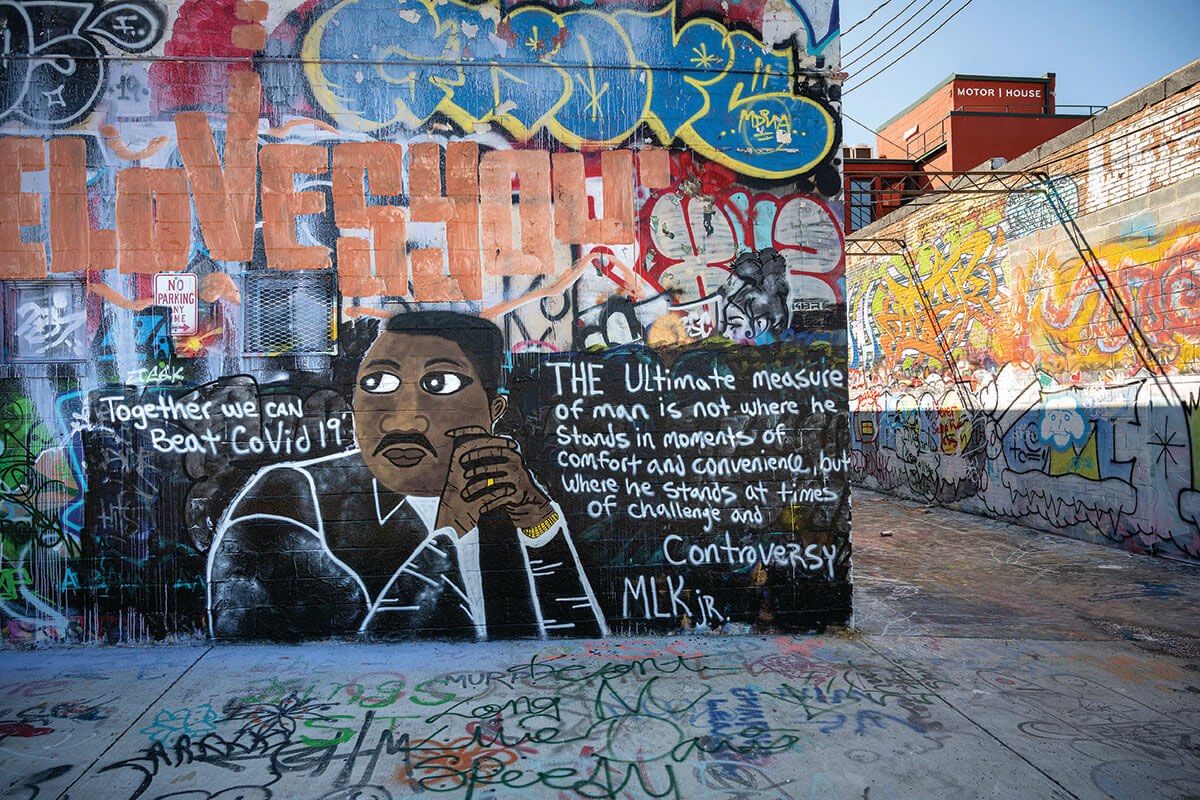

Acts of courage and kindness in the age of coronavirus.

IN THE FOLLOWING feature, we look at the people on the front lines of this deadly pandemic. Some, like doctors, nurses, and police officers, have chosen a life of public service. Others, like an intrepid group of makers producing hand sanitizer, took it upon themselves to step into the fray. And still others became accidental “essential” workers, forced, often by necessity or fear of losing a job, to serve the general public. For all of them, this virus has been unprecedented and daunting, but not without glimmers of optimism and hope. We hope you read and honor their stories.

A State of Dis-Ease.

As the coronavirus continues Its deadly spread, marylanders on the front lines risk their own health to help others.

By Ron Cassie

O

N THE WEEK OF St. Patrick’s Day, the Johns Hopkins Hospital intensive care unit where veteran nurse Kathleen Bailey works was silent and empty. Over several shifts, each patient in the two-dozen-bed unit had been moved to another ICU section on the East Baltimore campus. Bailey’s floor had been cleared as a precaution against a potential influx of COVID-19 patients, the first of whom from Maryland were just being diagnosed at associated Hopkins hospitals in Bethesda and Washington, where the capital region’s outbreak was in its alarming, beginning stages. “Within 24 to 48 hours, we were full,” she says. “Patients were arriving by ambulance and helicopter already intubated.”

Months later, Bailey’s unit remains full, and is still eerily quiet. Normally, the ICU’s private rooms and waiting area bustle with concerned parents, adult children, and siblings. Now, with visitation prohibited, families see their sick loved ones via iPads, placed on the bedside tables. With many of the infected heavily sedated, family members are left to simply stare at their unconscious loved ones, hooked to cumbersome breathing masks, as they pray for the best. “One family asked if we can stream 24 hours a day,” Bailey says. “Just watching them breathe, even with the help of a machine, provides so much solace.”

The 38-year-old Pasadena mother of two worked through the H1N1 virus outbreak a decade ago, but COVID-19 has changed everything, including her own daily ritual. She discards her protective gear after each shift and leaves her scrubs at the hospital to be laundered, showering and changing into her own clothes before heading home. She worries about bringing the virus back to her husband and children—her family reckoning with isolation like everyone else. The hardest part, Bailey says, is the helplessness in the ICU. Given that there’s no treatment for COVID-19, all staff can do is try to mitigate the disease’s devastating attack on the respiratory system—at its terrifying worst, a feeling of suffocation— and buy time for the body’s immune system to win the fight. “As an ICU nurse, you’re accustomed to people dying,” she says. “With this, people stay on a ventilator for three, four, five weeks, struggling to stay alive. I’ve cried. I’ve been a nurse for 15 years. I’ve never seen anything like it.”

Hopkins RN Kathleen Bailey after a 12-hour shift in the ICU on Mother’s Day. Photography by Gabriella Demczuk.

By the end of May, less than three months after the first confirmed case in the state, the pandemic had claimed the lives of more than 2,500 Marylanders, disproportionately in the state’s Latino and African-American communities. It’s a figure already more than double the number of Marylanders who died in the Vietnam War, with another 1,200 fatalities projected by the start of August. When the United States passed the grim milestone of 100,000 deaths from COVID-19 over Memorial Day weekend, the news came as some public health experts were warning that the novel coronavirus— much like influenza or measles—may never be fully eradicated, even after a vaccine is developed. Such diseases are referred to as endemic, and while their consequences are lessened, they remain resistant to eradication. There’s a newly approved vaccine for malaria, for example, which requires four shots, yet still has a poor-efficacy rate. For HIV, of course, no vaccine has ever been found. In Baltimore, a COVID-19 hotspot, it seems everyone already knows someone who has been infected or died from this new virus.

“In my lifetime, AIDS is the only other comparable pandemic and the valuable lesson there is that we need accurate testing, we need contact tracing, and we need education—in regards to social distancing, masks, and handwashing,” says Dr. Robert Gallo, the co-discoverer of the HIV virus, which causes AIDS. The director of the University of Maryland’s Institute of Human Virology and co-founder of the Global Virus Network, Gallo says COVID-19 is not likely to “just go away.”

In response to the tragic toll, Marylanders, for the most part, abided previously unimaginable restrictions put in place by Gov. Larry Hogan as restaurants, schools, and businesses were closed, and a stay-at-home order was issued on March 30. Baseball’s Opening Day, a tradition since the 1880s, was canceled along with other iconic spring and summer Baltimore events—the American Visionary Art Museum’s Kinetic Sculpture Race, the Maryland Film Festival, Flower Mart in Mount Vernon Place, Artscape, the annual African-American heritage festival AFRAM, and the July 4 Inner Harbor fireworks display. High school and college spring sports seasons were nixed along with proms and graduation ceremonies. The annual Balticon convention was held virtually. HONfest was scheduled to do the same. Preakness was postponed until October. The status of Pride Weekend remains up in the air.

Meanwhile, the extraordinarily contagious nature of the novel coronavirus impacted everyday life in innumerable ways, both quotidian and profound. Nursing homes suddenly became frightening places for our parents and grandparents to reside. Funeral services, along with grieving, moved online. Mundane things, like trips to the grocery store, became fraught experiences. Parents spent more time with their children, but were also forced to transition into at-home school teachers. Summer travel plans were scrapped; weddings postponed. At minimum, a gnawing stir craziness took hold. Jake Smith, the owner of the Baltimore Boxing Club in Fells Point, began going for extra milelong walks with his dog to ward off anxiety. “The whole family has been walking the dog like crazy,” Smith says with a laugh. “The dog is like, ‘I need a break.’”

Other issues rising from the forced isolation had more serious consequences. There has been a dramatic increase in calls to the state’s domestic violence hotline as victims stayed in lockdown with their abusers, fearful of coronavirus infection to the point where they’ve been unable to seek medical treatment for their injuries. As people stayed at home and alcohol sales skyrocketed, concerns about mental health and substance abuse rose amid the isolation—a particularly dangerous environment for those with addiction issues. In Baltimore, most of the hundreds of weekly Narcotics and Alcoholic Anonymous meetings moved to online Zoom platforms, though those in recovery say it doesn’t replace the face-to-face connections necessary for healing. “Recovery is all about social contact,” says Mike Gimbel, a former heroin addict and Baltimore County’s former top drug treatment official.

In the wake of Great Depression-level unemployment, thousands of parents across the state also suddenly struggled to feed their children. Others feared, and still fear, going to work.

“What this crisis is doing is starkly exposing the holes in our safety net,” says Susan Esserman, director of the SAFE Center at the University of Maryland’s School of Public Health in Baltimore, which works with trafficking survivors. Many essential employees in low-income jobs have had no choice but to keep going to work with little protection, she notes.

Patrick Moran, the president of AFSCME Maryland, the state’s public employee union, highlighted that many state workers serve in front-line jobs that were physically and emotionally stressful prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, corrections officers in prisons, which have seen outbreaks of the virus, are at a particularly high-risk for contracting the disease. “They’re already shorthanded,” Moran says. “And now they lack adequate protection and testing to do their jobs.” In Maryland’s nursing homes, where resident deaths represent the majority of fatalities in the state, at least 18 staff members have also died as of press time.

Video by Christopher Myers

Bailey before her may 10th shift. Photography by Gabriella Demczuk.

As the state approached 60,000 confirmed infections in June, a number that would nearly fill M&T Bank Stadium, miraculous recovery stories emerged as well. Michael Green, one of the first COVID-19 cases in Baltimore, survived 49 days on a ventilator at Mercy Medical Center. The 63-year-old lawyer, believed to have contracted the virus in New York the first weekend of March, remained in rehab into June. “There were times when it did not look like he was going to make it,” says his wife, Gail Green, who has seen her husband just twice during the entire ordeal, including briefly during his transfer from Mercy by ambulance to a rehabilitation center where he is still slowly being weaned off the ventilator and receiving physical therapy. By then, he’d lost 50 pounds and the ability to sit or stand. “The staff at Mercy was incredible,” says Green. “No matter how tired or overworked everyone was, a doctor called me every day. I talked to a nurse every shift. The chaplain, when she found out Michael was Jewish, lit Sabbath candles every Friday night and learned a Jewish healing prayer, which she said over him. The staff read messages to Michael from our two adult children— our daughter is expecting our first grandchild—once the breathing tube was removed from his mouth and placed in his trachea, and he was alert.” The Mercy staff also gave Green a celebratory sendoff and parade, the video of which went viral. “As much as that meant to us,” says Green, “I think that was for them, too.”

Among the countless anonymous heroes is Anne Arundel County ICU nurse Megan Pitt, who answered a plea for nurses in New York during the height of the outbreak there. She has three kids, which made the decision easier in some ways, harder in others.

“My husband is retired on disability from the military and so he could take care of the kids and our dog,” says Pitt, who at one point in New York was swabbed for the virus after a co-worker accidently knocked off her mask. “I’d been coming home from work here, changing and bagging my clothes in the garage, and putting them straight into the wash. I’m more afraid of getting them sick than me. My husband supports me 100 percent. He understands sacrifice. He was stationed overseas when we were first married. He calls it my ‘deployment.’”

▼ Health ▼

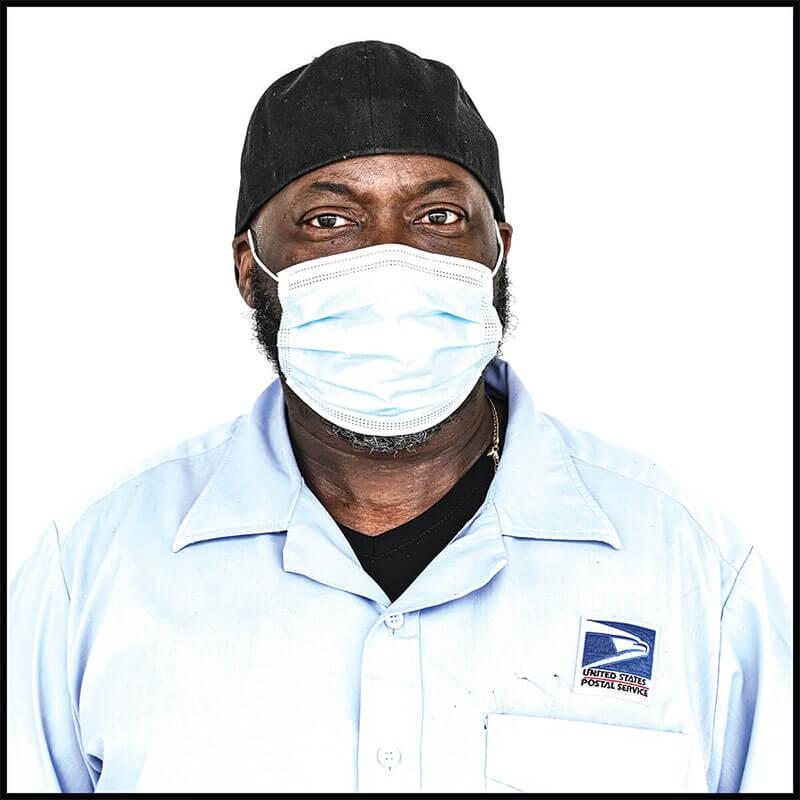

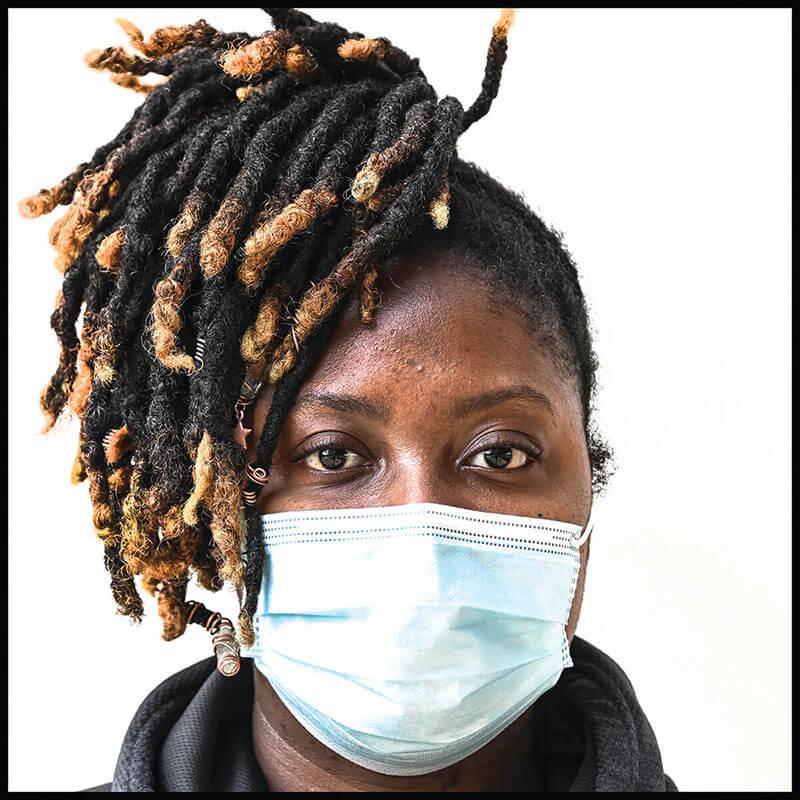

Photography by Mike Morgan.

Diagnosis

The

Test

▼

For public health nurse Nicole Brown, who oversees three drive-through COVID-19 testing sites for the Baltimore County Department of Health and Human Services, the most important thing she can do for her patients is create a soothing sense of order. “Although we can’t have a long conversation, the words that we give them are calm, to the point, and have clear instructions,” she says. “I think that’s what people want.” Patients roll down their windows to receive the test, which is a swab that goes all the way up the nose cavity to the back of the throat. “It’s very uncomfortable,” Brown admits. “I tell them it’s going to be the longest 10 to 15 seconds of their lives!” Despite her protective gear, Brown says she and her fellow nurses connect with every patient. “The nurses have kindness in their body language and eyes, even in their tone of voices,” she says. “It’s really remarkable to see.”—MW

Research

Searching for a Cure

He co-discovered the HIV virus. Now he's tackling the COVID-19 vaccine.

Dr. Robert Gallo knows viruses. Best known as the co-discoverer of the human immunodeficiency virus, which is responsible for AIDS, and as a pioneer in the development of the HIV blood-screening test, the Distinguished Professor in Medicine at the University of Maryland in Baltimore wants to emphasize that every virus is different. “Really different,” he says, like in the way every species in the animal kingdom is different from one another. “They all have different strategies, in terms of how they reproduce.” That said, Gallo, director of UMB’s Institute of Human Virology— as well as the co-founder of the Global Virus Network— is among those investigating whether the oral polio vaccine could prevent or reduce the spread of COVID-19 to immunized individuals. The vaccine has been documented to induce protection against other viral infections.

Ultimately, control of the coronavirus is possible only after a large part of the world’s population becomes immune, either through infection, which would be deadly for many, or by prophylactic vaccination. The oral polio trial is just one track in the worldwide hunt for a vaccine, one that would most likely supply limited immunity, but be better than no immunity at all. A second or third wave of the virus is “reasonably possible," Gallo says. COVID-19 is an RNA virus, a family of viruses which also includes the Zika and Ebola viruses, and no vaccine for an RNA virus has ever been licensed.

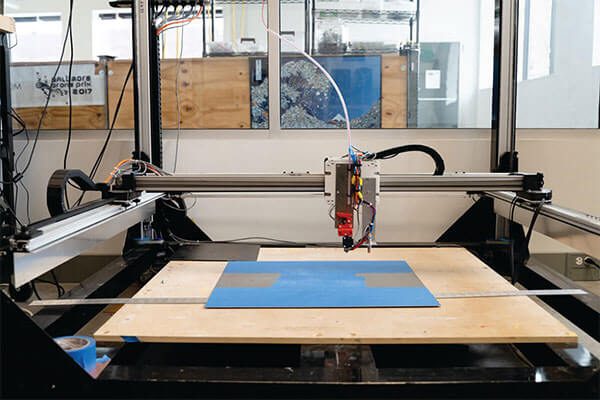

The state of Maryland, home to the NIH and the FDA, is playing an outsized role in global efforts for a vaccine. At Johns Hopkins University, multiple research projects related to COVID-19 are underway. Meanwhile, other researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine have begun injecting volunteers with a potential vaccine that targets mRNA, or messenger RNA, hoping to impart genetic information to cells that will stimulate the production of antibodies that can stave off the virus. Similar ramped-up efforts targeting messenger RNA are ongoing around the world, some with promising early results, but Gallo won’t predict when a vaccine will be ready. “You don’t have a vaccine that works,” he cautions, “until you have a vaccine that works.” —RC

Photography by Mike Morgan.

Life Support

Nevertheless, A Career Icu Nurse Persists.

Denny Marshall remembers when the first coronavirus patient arrived at the Mercy Medical Center. “March 18,” says the intensive care nurse. “We all know when that happened.”

A month prior, her floor had been partially converted into the hospital’s first COVID unit. Her six-nurse team was doubled to 12. Half of their 24 beds were designated for COVID patients. Doors were installed to contain the area. Now when she arrives at the hospital before 7 a.m., she gets a temperature check and fields questions about her own health before changing into new scrubs, shoe protectors, a hair net, and a full-face respirator mask.

“That’s our new normal,” says Marshall, who’s in her 36th year at the downtown hospital. “There has been a continuum of emotions. We’re learning as we’re going. It’s the unknown. It can be frightening. A lot of nurses are scared, afraid they’ll get their kids sick. Others are like, ‘Okay, let’s go . . .’”

The 60-year-old mother-of-three counts herself among the latter, which you can hear in her take-charge voice. At home, she’s resolved to social distancing from her firstborn grandchild, who arrived, like the pandemic, in early March. At work, she understands the leadership role her seniority requires for younger colleagues.

“We work together and help one another,” says Marshall. “ICU nurses are ready for the sickest patients. We’re problem solvers, we have the grit to handle difficult situations, and this has forced us to up our game.”

She spends her shifts moving swiftly between patients’ rooms to avoid potential exposure, but never wanders far. “You stay close, because you need to be able to hear the monitors, the IVs,” she says. “Things can change quickly.”

Marshall remembers the exchange with her fellow nurses when that first patient took a turn for the worse. “There was a lot of unspoken conversation,” she says. “All we see is each other’s eyes, but you could feel the energy. We were all thinking, ‘We have to make this happen, he has to get better.’”

And he has, now in rehabilitation and recovery. But they’ve had losses, too. “Death, always, whatever the reason. . . you just have to take a moment,” she says.

When she gets home in the evenings, Marshall leaves her shoes in the garage, throws her clothes in the laundry, and heads straight to the shower. She unwinds by watching CNN with her husband, Bob. By the time her next shift rolls around, she’ll be ready again.

“A lot has changed, but a lot has stayed the same, in that the care is still there,” says Marshall. “People say we’re heroes. We’re not heroes. This is what we do. We go to work. We care for the sick. And people get sick from the coronavirus, so we’re there to take care of them, too.”—LW

Illustration By Deanna Staffo.

Helping the Most Vulnerable

Eldercare Facilities Have Been Hit Hard During The Pandemic.

The first positive COVID-19 tests from a rehabilitation and nursing care center in the U.S. came back after the deaths of two residents at the Life Care Center of Kirkland outside of Seattle in late February. Exactly one month later, on March 28, Maryland officials announced an outbreak of the deadly coronavirus at a nursing home in Carroll County where 66 residents had tested positive, including 11 who had already been hospitalized. “It spread viciously where older people were exposed,” says Joseph DeMattos Jr., president of Health Facilities Association of Maryland, which represents skilled nursing and rehabilitation centers in the state. “We knew by March 11 the people most likely to contract the virus were 60 and over, and the people most likely to die were in their early 80s. We learned later that pre-existing conditions were a bigger factor than age, but of course most people in skilled nursing care fall into both groups.”

By mid-May, Maryland reported infections in 212 elder care facilities and nearly 1,000 confirmed resident deaths— plus an additional 18 staff fatalities. “The people working in skilled nursing homes in Maryland— the nurses, nursing assistants, support staff— have been heroes in the fight against this virus,” DeMattos says. “Sadly, they’ve also seen a lot of people die with COVID-19.”

In additon to the illness, there’s heartbreaking isolation. The staffs at nursing care centers in the state have gotten creative in keeping residents connected to family members in lieu of actual contact— facilitating window visits from patient rooms, as well as setting up iPad video connections and the placement of Alexa voice assistants on bedside tables. Stocking PPE for staff remains a challenge as does working day-in and day-out under such traumatic circumstances.

DeMattos says they're sending support teams and mental healthcare counselors to meet with staffs as needed. “We’re aware of the toll from the things they are witnessing and dealing with on a daily basis,” he says. “Many need, and will need, help processing everything.”—RC