Education & Family

Building STEPS Helps Students Become the First in Their Family to Graduate College

With a mission of addressing a lack of diversity in the science and technology fields, the org helps underrepresented local youth graduate from college and ultimately become STEM professionals.

Inside the Inner Harbor’s Colwell Center, Sarah Sterinbach is demonstrating how to use a pipette, a hand-held device that functions similarly to an eyedropper, but for use in scientific experiments. As she lifts it up and holds it vertically in her right hand, 30 high school juniors wearing lab coats and sterile disposable gloves do the same.

“Press the plunger down to the first stop,” instructs Sterinbach, a recent University of Pennsylvania grad and current Chesapeake Conservation and Climate Corps fellow. “Do you feel that? Okay, push the plunger down all the way. That’s the second stop. That’s going to expel all the liquid.”

Earlier in the morning, the students—visiting the Towson University Center for STEM Excellence through an education nonprofit called Building STEPS—learned about bioluminescence organisms, particularly bacteria sea life that produce and emit a “glowing” light. (Fireflies, as one student noted, are an example of non-sea life that produce bioluminescence light.)

Sterinbach explained how bioluminescence bacteria are used to detect and measure the impact of pollution. In basic terms, they are a reliable, relatively low-cost means of monitoring aquatic samples that may contain toxicants such as PCBS, pesticides, motor oil, diesel fuel, fertilizer, alcohol, etc.

The room had gone hush when Sterinbach turned off the lights and gently shook and lifted up a green glowing jar of bacteria in clean water. If the jar had not glowed, she’d noted, it would indicate no surviving bioluminescence bacteria—and thus contaminated water.

With an outline, the students, all from Baltimore City Public Schools, designed experiments to test potential contaminants and their impact on water purity—using their pipettes in the lab to place H2O, bioluminescence bacteria, and various liquid elements into test tubes.

“The motor oil and water didn’t mix,” a Digital Harbor student pointed out in the lab. “So there’s no glow near the oil, which is at the top of the test tube. But at the bottom, in the water, you can still see the glow of bacteria.”

The diesel fuel, his Dunbar High partner added, had mixed more completely with the water and killed nearly all the bacteria.

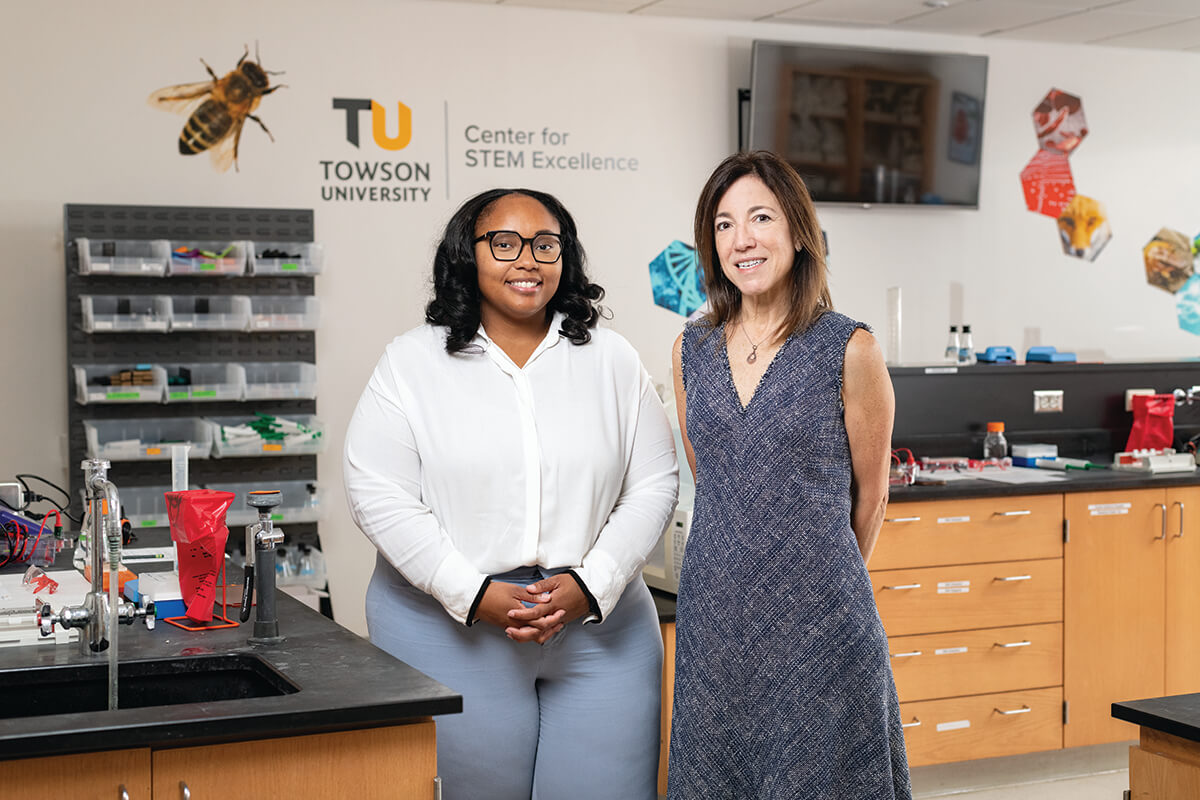

“Thinking through and designing an experiment, with all the protocols, is not easy stuff,” says Mary Stapleton, the director of bioscience education and outreach at TU’s STEM Center, who was suitably impressed by the students’ engagement and effort on this weekday excursion. “This is a college-level lab. It’s not something that I was doing at their age, and I have a Ph.D.”

Founded by Matthew Weinberg, president of regulatory sciences at the ProPharma Group, to address a lack of diversity in the science and technology fields, Building STEPS helps underrepresented local students graduate from college and ultimately become STEM professionals.

The program has evolved over the years, but it works like this: Building STEPS partners with Baltimore City Public Schools to identify motivated, high-achieving students in the 10th grade from resource-challenged schools and backgrounds.

After an initial application and get-acquainted process, they introduce the students in their junior year to science and technology professionals through seminar days trips to local hospitals, health and tech start-ups, research facilities like TU’s STEM Center, and campus visits, encouraging students to envision possible college and career paths. (Building STEPS offices are situated at Towson University.)

When each annual cohort of 80-100 students enters their senior year, the nonprofit assists them with college applications and financial-aid forms. The vast majority of each cohort—a remarkable 80 percent—become not just the first in their family to attend a four-year college, but to graduate, in good part because Building STEPS maintains its connection to students after they arrive on campus. They do regular in-person check-ins for in-state college students, find tutors if needed, and assist with academic and financial guidance throughout their matriculation.

One-third graduate with STEM or health care degrees and one-fourth go on to earn an advanced degree. After college, an ever-growing alumni network helps maintain those bonds when students enter the working world. When you look at the numbers, the program’s success is striking.

“The data shows that [only] six percent of students from the city high schools that we partner with go on to earn a four year college degree—it’s a little higher system-wide, eight percent, when you include schools like City College, School for the Arts, Western, Poly,” says chief executive officer Debra Hettleman, who has been with Building STEPS from the start.

A REMARKBLE 80 PERCENT BECOME THE FIRST IN THEIR FAMILY TO GRADUATE FROM COLLEGE.

The organization began by helping high schoolers find in internships, but quickly realized they needed to intercede earlier and more directly and maintain connections through college and beyond if they were going to make a real difference.

“Our students are essentially going through this process and going to college alone, even though they are generally going to college in-state,” Hettleman says. “We want to help them build community once they get to college. And, initially at least, that community is previous Building STEPS students already on campus, who are now upperclassmen.”

She adds that Building STEPS also has students who attend college outside Maryland, which the staff keeps tabs on virtually, but she believes it’s more supportive if a peer does some of the checking in. “It’s a developmental opportunity for the upperclassmen who do the relationship-building and mentoring, too,” Hettleman says.

In fact, the week prior to the students’ lab experience at TU’s STEM Center, Building STEPS’s current class of high school seniors met with staff, volunteer professionals, and Building STEPS college students to work on their financial aid and college applications and essays.

Seated in a first-floor conference room at the West Village Commons on Towson’s campus, the seniors worked on their. financial aid applications on their Building STEPS-provided laptops. Afterward, they moved to an upstairs conference room for one-on-one Zoom sessions with their essay tutor.

In its 25th year, Building STEPS now has a network of 150 volunteer professionals available to assist students. Among those on hand to support the seniors were De’Mon Kess, an Edmondson High grad now in ROTC and studying biology and premed at Morgan State, and Tavon Mitchell, a Patterson High grad in graduate school at the University of Maryland College Park.

Kess had initially attended the University of Maryland Eastern Shore, but got homesick and returned to Baltimore, taking a year off before restarting his education at Morgan. Taking a year off and transferring schools is the kind of interruption that can sometimes derail a first-generation college student, but Building STEPS maintained contact with Kess through the process, after helping plant a seed about a career in health care.

“Applying to Building STEPS in high school just opened doors for me,” says Kess, who recently began working part-time for the organization as well. “They got me an internship in high school with a radiation oncologist, and seeing what they do day-to-day, interacting with patients, made me realize I’d like to be in a career where I help people, too.”

Mitchell, who earned a Bachelor of Science degree in Kinesiology at Maryland before getting accepted into the school’s Master of Public Health program, says field trips to TU’s STEM Center and elsewhere inspired him in high school. At the University of Maryland, Building STEPS alums served as role models, a role he now embraces.

“They help with everything in the college process,” says Mitchell, also a first-generation college graduate. “They help with the financial aid part. All of my undergraduate degree and 95 percent of my graduate program has been free [nearly all Building STEPS students qualify for Pell Grants]. They help you work out a daily schedule, set aside study times, college advising. You’re not on your own.”

The overwhelming majority of Building STEPS are first-generation college students like Kess and Mitchell, which makes their success rate with students from some of the city’s most challenging neighborhoods all the more remarkable.

According to the Pew Research Center, students who have at least one college-educated parent are far more likely to complete college than those with parents with less formal education (70 percent to 26 percent). To put it another way, Building STEPS’s first-generation students are three times more. likely than first-generation students nationally to graduate within six years.

While college is not for everyone and a degree is not needed for every career, the wage gap between high school and college graduates has been widening for 40 years. And it climbed significantly last year, per data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

The median wage for a recent college graduate in 2023 shot to its highest mark, $60,000. The median wage for high school graduates grew as well, but only to $36,000. The gap in career earnings grows even wider with those who earn graduate degrees. According to the Social Security Administration, men with graduate degrees earn a median of $1.5 million more throughout their lifetime than high school graduates. Women with graduate degrees earn $1.1 million more.

After a quarter-century equipping students for college success, there have been plenty of full-circle moments for the nonprofit. Asia Cole, for example, who earned a Bachelor of Science degree in Speech Pathology from Towson University after graduating from Digital Harbor High in 2014, came back to Building STEPS five years ago and now serves as the nonprofit’s hands-on director of outreach and engagement.

“I was definitely a nerdy, teachers-favorite-type student in school with a lot of interests,” Cole says with a smile. “I was interested in the sciences, health profession, that type of stuff, and working with Building STEPS, in an indirect way, is still working in the area. For me, my mother and father didn’t go to college, my father did not graduate from high school, so we had a lot of learning to do.

“My grandmother was a big motivator for me,” Cole continues. “She never wanted me to settle for less than what she knew I could achieve, and first learning about Building STEPS and getting that support that I needed through the college process really made a difference in where I ended up after high school.”

The biggest full-circle moment, however, is still a work-in-progress, but scheduled for completion the fall of 2026.

Deon Avery was one of the students in Building STEPS’s very first cohorts. “I was just a little Black girl from Southwest Baltimore. My father had died when I was three and I was raised by a single mom in a low-income community,” the former Baltimore City assistant principal and Washington, D.C., school principal explains. “If you look at the statistics, the odds were against me, but programs like Building STEPS showed me the possibilities for what I could build my life into. I still remember going to a technology company and learning about all the different types of engineers there. And going to another company and meeting graphics designers and artists at work. I did not know jobs like that existed. It motivated me to forge forward and to just try.”

Ultimately, she focused on education, the importance of which came to mean so much to her. She eventually earned a Ph.D. in Education and is now working to bring the first Montessori high school to Baltimore and will serve as the Charm City Garden Montessori School’s principal when it opens for the 2026-27 academic year.

“We’re looking at the southwest side of Baltimore, specifically the Saint Joseph neighborhood where I grew up. It’s a long process to put in the application and get the building deal done, so we are working on those things, but that is the community where we would like to open our doors.”

In the meantime, Avery has another pressing issue. Her daughter is in 12th grade at Western School of Technology & Science and planning her future.

“She’s 17 and she is on her way to college and we’re enjoying receiving all of the college acceptances and the award letters,” Avery says. “We’re just waiting to get all of them so we can make a final decision about where she’ll attend.”