Food & Drink

Market Value

From public markets to lake trout, Baltimore has an eclectic food history.

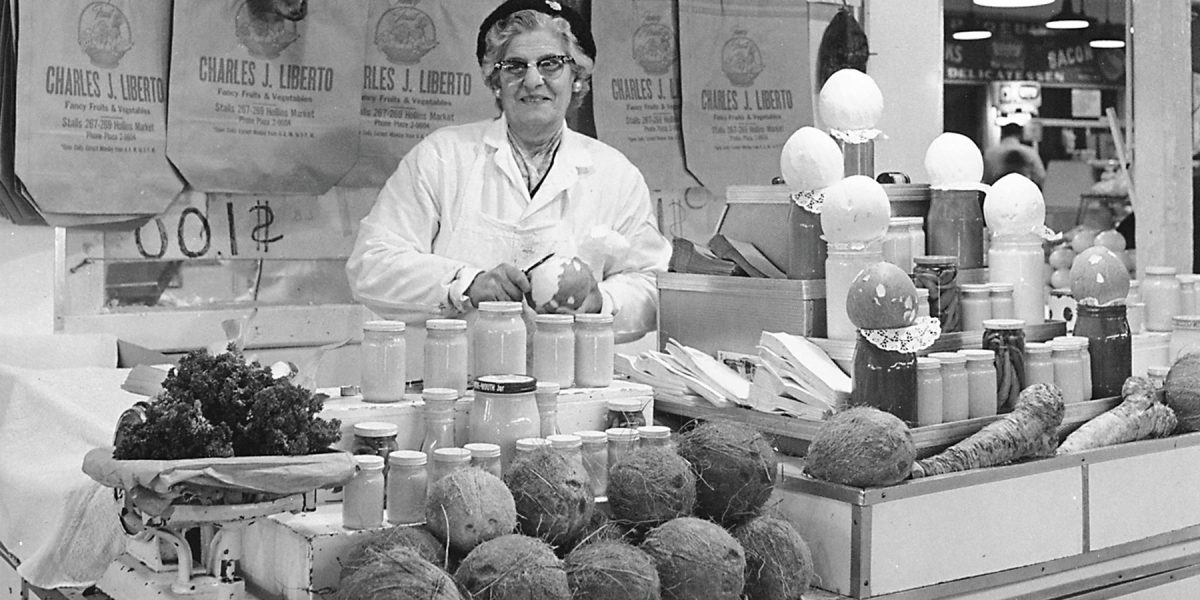

Years ago, the busiest blocks in Baltimore were not down by the Inner Harbor. Instead they were scattered all across the city, centered around the 11 public markets that acted as each community’s epicenter of commerce, cuisine, and culture. Neighborhoods were literally built around the block-long structures, where farmers and merchants peddled livestock and produce, and all walks of city life converged around the sights, sounds, and smells.

Today, six markets remain in the country’s oldest public market system, all with roots that date back to at least the 1800s. Sure, most have become a little rough around the edges, but they’re not without their lingering charms, offering a reassuring sense of place to generations of Baltimoreans in an ever-changing city. Familiar smells greet you in the corridor, while faded signage makes long-standing businesses feel timeless, like a place your grandparents frequented, and hopefully your grandchildren will, too. These markets are where Baltimoreans have eaten their first crab cakes, gathered over Natty Bohs, and shopped for fresh groceries in a city now beleaguered by food deserts.

“There is a lot of potential in restoring these spaces to their former glory.”

But with age comes a need for maintenance, and traditions are difficult to sustain without some sort of investment. Public markets are owned by the city, and they have long suffered from swings of neglect and declining foot traffic as shopping options change. But while they’ve been left to languish, several of the surviving markets are now undergoing multi-million-dollar, public-private transformations: Cross Street Market in Federal Hill, Hollins Market in Pigtown, and Broadway Market in Fells Point, which will be partially converted into a high-end crab house.

“Baltimore was a great market city, and it is to this day,” says architectural historian John Gentry. But the system’s ability to survive relies on a “values-centered approach to preservation,” he notes, with ideal redevelopment tailoring to both community needs and local planning goals. Walkability tends to make markets attractive to transit-focused city officials, while their affordable food options make them appealing to socially conscious urban planners.

GO FISH

Lake trout continues to make a splash.

By Michelle Harris

If there’s one iconic food as underdog as Baltimore, it’s not crab cakes or pit beef. It’s (close your ears, tourists) the one and only lake trout. Much like the city itself, it’s a fried fish of contradictions.

First of all, it doesn’t come from a lake. And, oh yeah, it isn’t trout! In most cases, it’s whiting, or silver hake, from the Atlantic Ocean, with local folklore tying its name to being the last fish to market, aka “late trout.” Over time, with our accents taking over, the new name stuck. And while it’s not from the Chesapeake, we still consider it our own, serving it up at Lent suppers, fish fries, and, of course, at nearly every corner store. (We even had one beloved local rock band named in its honor.) Wherever you grab it, just be sure to douse it in hot sauce with a side of western fries.

There is a lot of potential that lies in restoring these spaces to their former glory, both culturally and economically, but Gentry also notes that critics often consider such projects to be “agents of gentrification.” Though several developers have committed to coordinating with the Baltimore Public Markets Corporation—which works to ensure that markets remain community hubs, while also addressing food, nutrition, and public service needs—new food halls tend to bring trendy vendors not affordable to all, and higher-income consumers create a valid fear of displacement among legacy residents. The Mount Vernon Marketplace does include a produce stand, while R. House’s developers offer affordable housing for area teachers, and both spots have become cross-cultural hangouts. But even still, it’s hard to envision the old stalwarts reinvented in their sleek, chic, new image.

The real litmus test may lie in the granddaddy of them all—Lexington Market—the oldest city market, having been originally constructed in 1782. World-class crab cakes aside, the landmark has seen better days, with a tired interior, the occasional viral rat video, and an exterior strained by crime. While previous plans included razing and rebuilding, it was recently announced that the market’s long-anticipated redevelopment will be handled by Seawall Development, the brains behind R. House and other redevelopment projects in Remington. Construction on new and existing structures is set to begin as soon as late 2019.

“We believe that real estate should be used to empower communities and unite our cities,” says Thibault Manekin, co-founder of Seawall. “There are few cities in America that are in more need of being united than Baltimore, and there is no greater historical institution than Lexington Market to be the tipping point that brings us all together.”

What Charm Means To Me...

“The charm that brought (and kept!) my great-grandfather here after he emigrated from Italy through Ellis Island was in our city’s paradoxes. Baltimore has all of the benefits of a big city, while still maintaining the familiarity of a small town. Baltimore has all of the modernization of a northern city, while keeping the famous hospitality of the south. Our Inner Harbor and Camden Yards revolutionized and defined charm, which has been emulated across the country for decades now.”

Lou Catelli | Hampden's unofficial mayor

HORSING AROUND

Moveable Feast

For centuries, Baltimore City residents have cherished the charming clip-clop of horses’ hooves and the hollers of “Tomatoes!” or “Watermelons!” coming around the corner. A time-honored tradition passed down among generations of African-American families, the produce salesmen known as arabbers (pronounced ay-rabbers) have been peddling fresh fruit and vegetables via colorful, horse-drawn carts since the 1800s. But while their horses once speckled the city, their presence is more of a novelty these days, as regulations and urban renewal have strained the practice. Crossing paths with an arabber now feels a bit like spotting a white rhino, but in neighborhoods where healthy food is scarce, they still serve as mobile markets and survive thanks to the patronage of loyal customers. A motto for all Baltimoreans to live by: An apple a day allows the horses to stay.

last supper

An ode to the iconic eateries of yesteryear.

By Richard Gorelick

Over the years, Baltimore's hallowed haunts have all had their own claims to fame. Haussner’s, for its a garish art collection. Louie’s Bookstore Cafe, for its inefficient service. Gampy’s had sassy late-night waitstaff. Martick’s, for its crotchety owner. This was all part of their charm, and most diners knew what to expect going in—even looked forward to it.

Today we mourn these bygone places perhaps more than other restaurants that arguably served better food. It might be because Baltimore now seems to have a critical shortage of eateries with real character. It’s probably a sign of the times—and likely a consequence of rising rents and changing dining habits. Or maybe quirk has just had its day. Not just in the places we eat, but everywhere. Among the anxieties associated with gentrification is the eradication of the unique.

A few of the old-school spots remain, like Werner’s on Baltimore Street, serving what we used to call “businessmen” for six decades, and The Prime Rib, which still has leopard-spotted rugs and a tuxedoed pianist tickling the ivories. Even Peter’s Inn has come back to life, with its Playboyed bathroom walls.

But these days, we have a new kind of only-in-Baltimore restaurant. Spots like Dovecote Cafe, Clavel, or Ekiben, which are all openly devoted to nurturing their communities, while also serving good food.

Years from now, when these places close, we’ll undoubtedly moan: They don’t make ’em like they used to.