Food & Drink

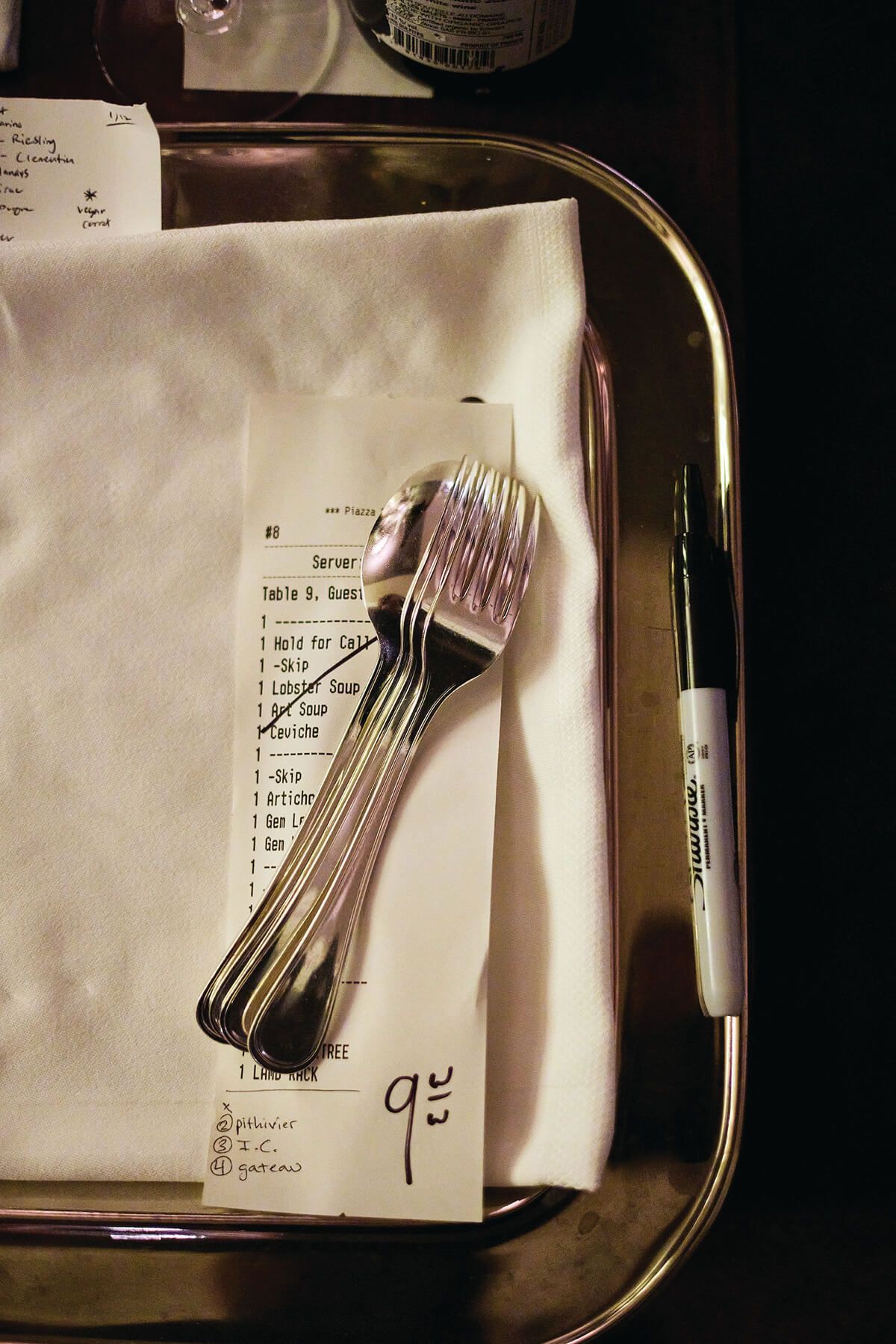

Baltimore’s Front of House Workers Share Their Stories from Behind the Scenes

We shadow six hospitality workers who all agree that, despite the hardships of the past years, restaurant life is getting back to pre-pandemic times.

For many years, Richard Gorelick explored the workings of Baltimore restaurants, writing food reviews for The Baltimore Sun and other publications. After taking a break, he’s back in the business—this time on the other side of the restaurant world as a host at Foraged in Station North.

“My job is to manage the people coming in and to make sure that they’re seated in a way that doesn’t tax the kitchen too much,” Gorelick says. “It’s fun. It’s like playing Jenga, switching tables and trying to make sure individual servers aren’t overwhelmed.”

Gorelick, who has been at the restaurant since 2021, when it relocated from Hampden to its new location, likes being part of the front of house.

“It’s a great fit for me,” he says. “I really like it there. It’s what I imagined. The front of house works as support for the kitchen.”

In restaurant lingo, the front of house includes the parts of a restaurant that a customer sees, including servers, bartenders, food runners, and bar backs, and operations like table and bar service. The back of house refers to areas most diners don’t experience, like the kitchen, prep areas, and offices.

While several fields were interrupted by the pandemic, none was affected more so than the hospitality industry. At the height of COVID, many front-of-house staff were laid off as restaurants struggled to remain afloat—others left by their own choice in droves. The volatility of the hospitality industry, the health risks associated with COVID, and worker burnout all contributed to the massive loss of hospitality jobs in the U.S. since February 2020.

But luckily for us, some workers, like the six people we spoke with below, stuck it out. (One even joined the industry on the tail end of the pandemic.) Most of our interviewees agree that, despite the hardships of the past years, restaurant life is getting back to pre-pandemic times.

Peter Keck

Charleston

Maître d’hôtel Peter Keck is the go-to guy at Charleston in Harbor East. The fancy French title on his business card simply means he manages the restaurant, he says.

Though he downplays his role, the restaurant was recently named a semi-finalist for a James Beard Award for Outstanding Hospitality, which is no small feat. If something is amiss with a diner—their table isn’t ready when they arrive, for instance—Keck will step in to smooth out the situation, maybe offering a free glass of wine.

“The best part of my job is I get to make people happy and call that my career,” he says. “The worst part of my job is that sometimes you feel like you are the black hole for everything that’s going wrong.”

Keck has been with the owners, chef Cindy Wolf and Tony Foreman, since they opened Savannah in Fells Point in 1995. While he’s taken a few breaks when his daughters, now 25 and 22, were younger, he has spent most of his career with the business partners. He’s held various positions during his tenure, including as beverage manager in Charleston’s early days. He recalls one evening when a regular guest sat at the bar chatting after his dinner and left a $1,000 tip on an $85 bill.

“It was over the top,” Keck recalls. “It’s not every day you get to pay your rent with a tip.”

Currently, his official 10-hour day at Charleston starts at 4 p.m., but the Fells Point resident deals with myriad issues before even walking in the door. The text messages from staff start around 11:30 a.m., he says, with missives like: “Something is on fire.” “This staffer has a sick child.” “This person fell off a scooter.”

“THE BEST PART OF MY JOB IS I GET TO MAKE PEOPLE HAPPY AND CALL THAT MY CAREER.”

Once at work, he checks in with the staff before service begins to address any other concerns. There are typically about 23 front-of-house workers, from servers and bartenders to hosts and food runners, on duty each night. Despite being impeccably dressed in an Ermenegildo Zegna Italian suit, Keck has been known to climb a ladder and peer into the ceiling to fix a clogged pipe during his day. But mostly, he circulates through the restaurant interacting with customers.

“I’m driven by the expression on people’s faces and the atmosphere in the dining room,” he says. “That’s all the bottom line I need, people smiling and telling us they will come back again.”

At 57, Keck has no plans to slow down, but he has thought about the future.

“Tony and I talk about being two old guys who hang around the wine shop and pop into the restaurants,” he says with a laugh. “I don’t know how likely that is to happen, but I’m sure we will fulfill that to a certain extent.”

Aaron Day

The Prime Rib

Aaron Day, who has been lugging plates of juicy beef at The Prime Rib since 1973, rattles off an impressive list of diners he’s waited on: Rosa Parks, Mohammad Ali, Joe Frazier, Oprah Winfrey, Montel Williams, Liberace, and Maya Angelou, to name a few of the famous folks who have graced his tables. In the beginning, Day used to get starstruck by the celebrity clientele.

“I would get a little intimidated,” he admits. “But now, it’s kind of easy.”

He remembers talking to Parks about Dr. Levi Watkins Jr., a Johns Hopkins heart surgeon who implanted her pacemaker and would bring her to the restaurant on her check-up visits to Baltimore. Occasionally, Day will drive his well-known customers to their lodgings. One evening, he chauffeured Tom and Dick Smothers of the Smothers Brothers comedy-musical duo to the Lord Baltimore Hotel.

“They lit up some marijuana and told me not to tell anyone,” Day says. “I was worried the police would pull me over.” They didn’t.

Local hotshots also make their appearances at the restaurant, from Ravens kicker Justin Tucker (he’s gracious about taking selfies with diners, Day says) and Fox45’s Kai Jackson to attorneys Billy Murphy and Warren Brown.

“This is where everybody in Baltimore City comes for a dining experience,” he says.

Day, who grew up in Edmondson Village, started at The Prime Rib as a busboy when he was 15, moving up to a waiter position when he turned 21. He was the only African-American server in the dining room at the time, he says, and was thrilled to be more than doubling his salary. He has been a stickler about finances since he was a boy, cutting grass for his neighbors and learning about the stock market.

“I would go to the bank every day and put money away,” he says. “I came away with this thing for saving money.”

In high school, he bought his first car: a white 1970 Lincoln Continental. “The police used to pull me over two or three times a day and harass me a little bit,” he recalls. “They wondered how a guy like me could afford a car like that. I told them I worked at The Prime Rib.”

Now, Day, 65, arrives at the restaurant around 3:45 p.m. four nights a week to set up his station and make sure each place setting is pristine. He changes into a black tuxedo, the required attire for servers, before the first diners arrive at 5 p.m., usually finishing up his duties at 11 p.m.

He’s going to work as long as his legs hold out, he says. When Day does retire, he plans to trade stocks, take care of his family (a son, daughter, granddaughter, and grandson), and, oh, go out to dinner.

Oscar Galvis

Restaurante Tio Pepe

Oscar Galvis had no idea when he started working at Tio Pepe in 1975 that he’d be waiting tables at one of Baltimore’s longest running restaurants 47 years later.

“I like the people, and besides, it’s a living,” he says. “That why I stay there.”

He’s witnessed wedding proposals and various celebrations in the past decades, but he particularly remembers a couple who met at Tio Pepe on a blind date years ago. The couple eventually married and still come to Tio Pepe, he says.

Galvis, a Colombia native, was drawn to Baltimore because of a romantic interest when he was 19 years old. Looking for a job, he headed to Tio Pepe, known for its Spanish-Mediterranean cuisine, after a friend urged him to apply because “they needed Spanish-speaking people,” he says.

The bilingual Galvis was hired as a busboy, happily slipping into the signature gold jacket that’s the uniform of the job. But the eager worker soon donned a blue jacket as a food runner, working his way up to server with the coveted red jacket of the position.

The colorful, formal attire has been worn since the Mt. Vernon classic opened in 1968. And while much of the old-school restaurant hasn’t changed, there have been some adjustments. Lunch is no longer offered, and the workers, who once toiled six or seven days a week, have more manageable hours.

“TO HAVE ALL THESE PEOPLE, SECOND, THIRD, AND FOURTH GENERATIONS, COME HERE IS THE BEST PART.”

Galvis, now 69, works between three and five days a week, starting at 5:30 p.m. The years have taken a toll on him physically, though, causing knee problems. He shrugs off the discomfort, saying, “That’s part of life.”

During his work evenings, Galvis juggles up to nine tables a night, depending on how busy the restaurant is. His secret to dealing with diners: “You need patience,” Galvis says. “You have to make things more relaxing.”

Over the years, he’s watched customers bring their children, grandchildren, and even their great-grandchildren to the restaurant. That’s his reward, he says: “To have all these people, second, third, and fourth generations, come here is the best part.”

Jillian Garner

Kooper’s Tavern

At 26, Jillian Garner sees waiting tables as a means to an end. “I want to start on a psychology degree,” she says. “I’ve always dreamed of being a Towson Tiger.”

Garner, who lives in the Oliver neighborhood of East Baltimore, strives to be financially independent. “I have to do everything on my own,” she explains. “I have to put myself through [school].”

After graduating from Glen Burnie High School, Garner enrolled in a medical-assisting program at a local trade school, ending up at a plasma center. She realized that wasn’t her calling and took a job at Outback Steakhouse in Canton in 2018. She eventually ended up at the now-closed Lucky Buns in Fells Point in early 2022. After rumors flew that the restaurant was closing for “renovations,” she applied for a job at Kooper’s Tavern in Fells Point and has been a full-time server since last April.

“I decided to give it a try, and I love it,” she says. Garner starts her five-day workweek at 9:30 a.m. on weekdays and at 9 a.m. on weekends, when she works double shifts. “It’s a good money maker,” she says with a laugh. “I’m always down for a dollar.”

Before diners arrive, Garner gets the tables ready and sets up the silverware, among other duties. She appreciates the customers who engage with her.

“I love that they ask me for my name and ask me how my day is,” she says. “It makes a huge difference.”

She’s also prepared for cranky customers. “Of course, we have moments when people aren’t happy, and we do everything to make it right,” she says. “Even if we think they’re not going to tip, everyone gets treated the same way with a smile.”

Thebonus is the people she’s met. “I’ve made great friends along the way,” she says. “The clientele is a family in itself.”

Teresa Marconi

Thames Street Oyster House

Only Teresa Marconi can make wolffish—an Icelandic specimen prized by chefs for its sweet, crab-like texture—sound like a dish you’ve been waiting for your whole life.

She’s done research on the fish, a special on some evenings, before she even approaches the upstairs tables she waits on at Thames Street Oyster House, gleaning information from executive chef Eric Houseknecht and exploring questions like, “How ugly is a wolffish? How lean is the meat?” Her resulting spiel gets everyone’s attention.

“People don’t know what this stuff is,” she says. “How will they order it if I don’t tell them?”

Marconi, who has been with the Oyster House almost from the beginning, when it opened in 2011 in Fells Point, takes great pride in ensuring the restaurant’s diners leave satisfied.

“I like to make people feel like they’re in good hands with me and the food,” she says.

One of her customers drives from out of town just to order the restaurant’s signature five-pound lobster stuffed with crab, shrimp, and scallops. He’s ordered it so often—probably at least 10 times over the years, Marconi says—that the kitchen has named the dish “The Paris Brown” after him.

“He and his wife eat what they can and take the rest home,” Marconi says. “Then, they eat it for the rest of the week.”

“WE’RE BACK TO BEING BUSY. IT’S PRETTY MUCH A STRAIGHT RUSH. THERE’S A LOT OF PHYSICAL WORK TO IT.”

Marconi, 60, has been wowing customers since 1983, when she worked as a summer waitress at Brass Balls Saloon in Ocean City to earn money to pay for college. Even after she graduated from then-Towson State University with a degree in mass communications, she leaned toward the hospitality business, settling in at John Steven Ltd. in Fells Point for 14 ½ years before following her friend, chef-owner Jason Ambrose, to Salt Tavern in Butchers Hill in 2006.

Along the way, the Idlewylde resident and her partner, Bruce Dombeck, had two sons: Clay, who is now 23, and Beau, 18.

During the pandemic, Marconi helped with the Oyster House’s carryout service and outdoor customers until the restaurant was fully operational again.

“It feels the same to me now,” she says. “We’re back to being busy.” Marconi’s day starts around 3 p.m., when she checks in for her shift, setting up the dining room and making sure the wine station is organized. At 4:30, diners begin to arrive for what Marconi calls “four and a half hard hours.”

“It’s pretty much a straight rush,” she says. “There’s a lot of physical work to it.”

She usually avoids making any serious mistakes during service, though occasionally she’ll inadvertently knock over a diner’s water glass (“Thankfully, not red wine” she says.) And, sure, various local sports figures like Ravens kicker Justin Tucker and linebacker Joshua Bynes pop in, but everyone gets the Marconi treatment if they’re sitting at one of her tables.

“They’re VIPs,” she says. “But everybody is a VIP to me.”

Richard Afrookteh

The Bygone

Richard “Rich” Afrookteh at The Bygone in Harbor East came into the hospitality field in a roundabout way. First, he practiced law; then, he became a business owner, running a bus company that transported students to private and parochial schools.

But in 2018, Afrookteh realized it was time to pursue his dream of working in the restaurant field.

“I decided that I’m going to do what I really wanted to do and be in the food industry,” he says.

Today, at The Bygone, he serves a range of customers, from groups of teenagers celebrating birthdays to prominent diners with deep pockets. Recently, he waited on a couple who enjoyed a meal with pricey bottles of Champagne and red wine. At the end of the $3,000 meal, the husband tacked on a $2,500 tip.

“I was floored,” Afrookteh says. “I still have the receipt.”

Afrookteh, who grew up in Catonsville, had always been fascinated by food, influenced by his dietitian mother, TV cooking shows, and watching his grandmother cook. After high school, he worked as a server in Ocean City, where he experienced one of his most embarrassing incidents, at Mario’s Italian Restaurant.

Afrookteh was dishing out scoops of shrimp scampi from a serving dish to a table of diners when a man began gesticulating, causing the dish to tilt and drip some of the gooey contents onto the man’s toupee.

“He had venom in his eyes,” Afrookteh recalls. “It was mortifying.”

That didn’t deter the 19-year-old from wanting to pursue a hospitality career. However, his father, a general surgeon, “never supported that kind of notion,” he says, so he went to the University of Delaware and then University of Baltimore School of Law before working in the Maryland Office of the Attorney General.

When Afrookteh’s children arrived—two daughters, now 28 and 25—he went into private practice. After he left the bus enterprise, he saw an opening for a server at the now-closed Alexander Brown Restaurant in downtown Baltimore.

“I applied online, and they hired me,” he says. “I thought, ‘I guess I can get back in the front of house.’”

When the restaurant closed during the pandemic, Afrookteh, who lives in an Inner Harbor condo, headed to Antrim 1844 in Taneytown and The Valley Inn in Lutherville before landing at his current post in April 2021.

“When I arrived, I was nervous about The Bygone, wondering, ‘Is it going to be corporate and stuffy?’” he says. “But the Atlas Group was very welcoming.”

Afrookteh, who wears a blue dinner jacket, black slacks, bowtie, and white shirt for his role, arrives at the restaurant’s 29th-floor dining room by about 3:45 p.m. on workdays to prepare for pre-shift meetings and the family meal, when staff members share food before their shifts begin. Dinner service starts at 5 p.m.

“Once I’m finished, I’m home at 11 p.m. or midnight,” he says. “It’s a long day.”

The effort is worth it if his diners enjoyed their meals. “I don’t think I do anything unique,” he says. “I try to allow people to experience the feeling they want in that moment. I want them to feel that No. 1, they’re welcome, and No. 2, that this is a place where they are special.”