Food & Drink

Let Them Eat Crab Cakes

After more than a century, the fifth-generation Faidley’s Seafood lives on as the king (and queen) of Maryland’s most iconic dish.

BEFORE THE MAGIC HAPPENS, Nancy Faidley Devine puts on plastic gloves to protect her rings and immaculate pink fingernails. Next, she dons a thin plastic apron, above which she ties one of a more substantial white cloth. The two layers of protection are necessary because the secret sauce can stain.

Into a large bowl, she dumps one pound of lump crab meat—always from Maryland when it’s in season—then a pre-measured bag of saltine crackers that have been broken into dime-sized pieces by one of her employees. They can’t be too small, because she doesn’t want crumbs clinging to the meat, but if she spots one that’s too big, she snaps it in half. She sprinkles a dash of Old Bay—not too much, lest the mixture become too salty—and some dry mustard, then adds three ladles of that sauce from a four-gallon bucket.

From her perch in the corner near the front doors, about three feet above the weathered floor that slopes from Paca Street toward Eutaw, Devine begins hand-mixing the ingredients that she forms into what many people believe are the best crab cakes in America’s crab cake capital.

She takes great pain not to knead the meat or treat it too roughly so those magnificent lumps don’t break apart. Instead, she slowly burrows her fingers into the pile, then gently folds.

“I watch people put crab meat in a bowl and take a spoon or fork to it,” she says, bewildered. “I think, ‘Oh my god, they’re messing this up.’ You buy something that’s premium like this and then you take a fork to it?”

People in line on this February day—and there was almost always a line before the coronavirus shuttered Lexington Market—waiting to order, whether for the first time in their lives or the four-hundredth, watch mesmerized as she scoops up fistful after fistful, shaping each into a cake somewhere between the size of a baseball and a softball.

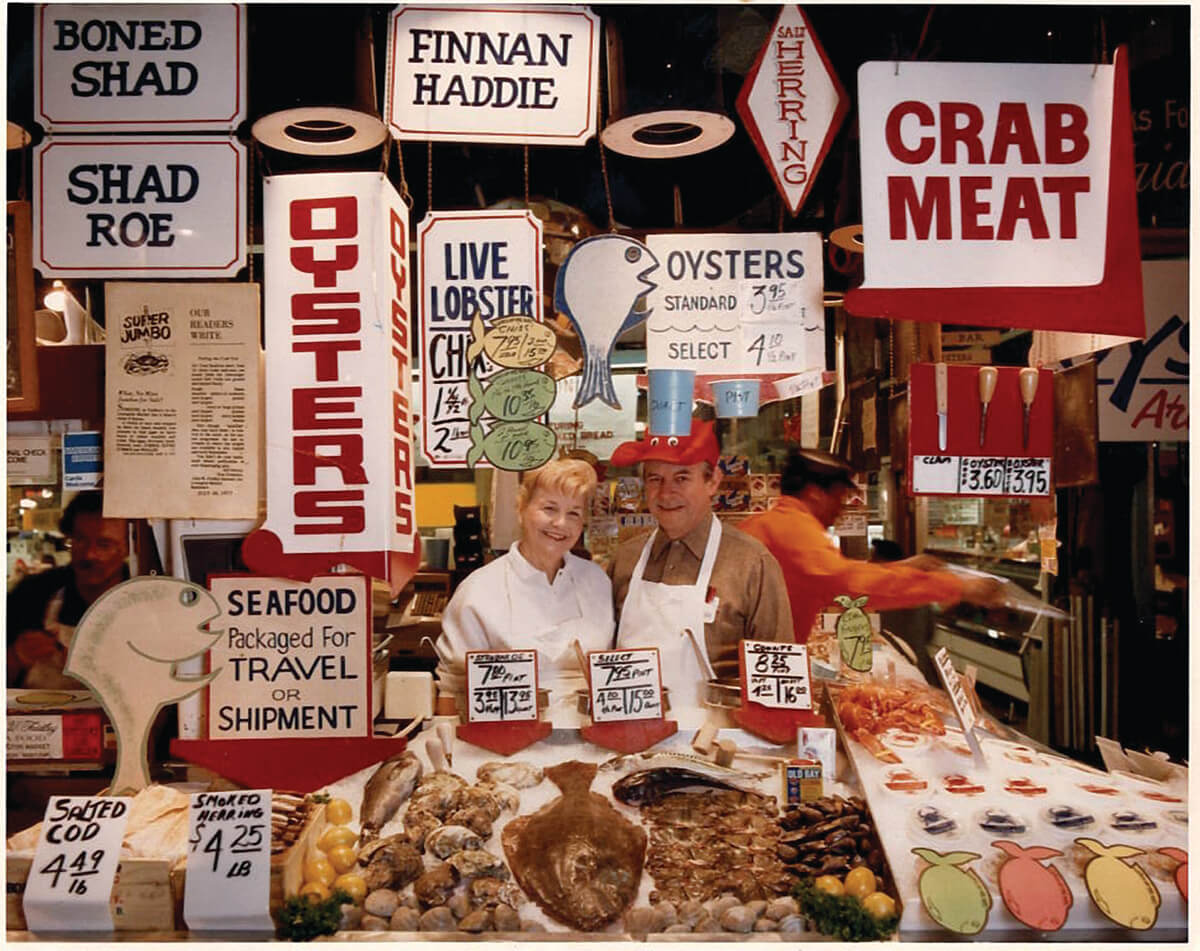

These simple yet universally beloved spheres, lined 20 to a tray then refrigerated before being fried or broiled, are what initially lure people from around the world to Lexington Market, the oldest public space of its kind in the U.S., where Nancy’s grandfather opened this seafood business in 1886. But the woman making them, along with her husband, Bill, and their cheerful and loyal staff are what keeps them coming back.

She emits a grandmotherly warmth, chatting with customers she reflexively calls “honey,” posing for pictures, holding babies, and even signing autographs. With her coiffed blond hair and red lipstick, it’s almost as if she’s a politician on the campaign trail, supported by 100 percent of the electorate. Her platform: It’s the crab cake, stupid.

“How many places do you go where you see the owners walking around, talking to the customers, making sure they’re comfortable?” asks regular Joseph Jones while enjoying fried clam strips and a Budweiser for lunch at one of the communal tables. “They make you feel welcome. If I was officially part of her family, I’d live here.”

Like nearly all of the customers, Jones is standing, as are Nancy in her cake-making corner, Bill at his standard spot near the cash register, the oyster shuckers behind the raw bar, and the fishmongers at the retail counter. There are no chairs at John W. Faidley Seafood, a design element that makes the place feel more egalitarian than any other spot in the city.

“It’s like a community center, not a restaurant,” says former Senator Barbara Mikulski, who’s been friends with Nancy since the two attended high school together at the Institute of Notre Dame. “Everybody thinks of the crab cakes, which are among the top five—don’t ask me who’s number one—but Nancy and Bill are really the spirit of Baltimore and what the markets have meant and should continue to mean.”

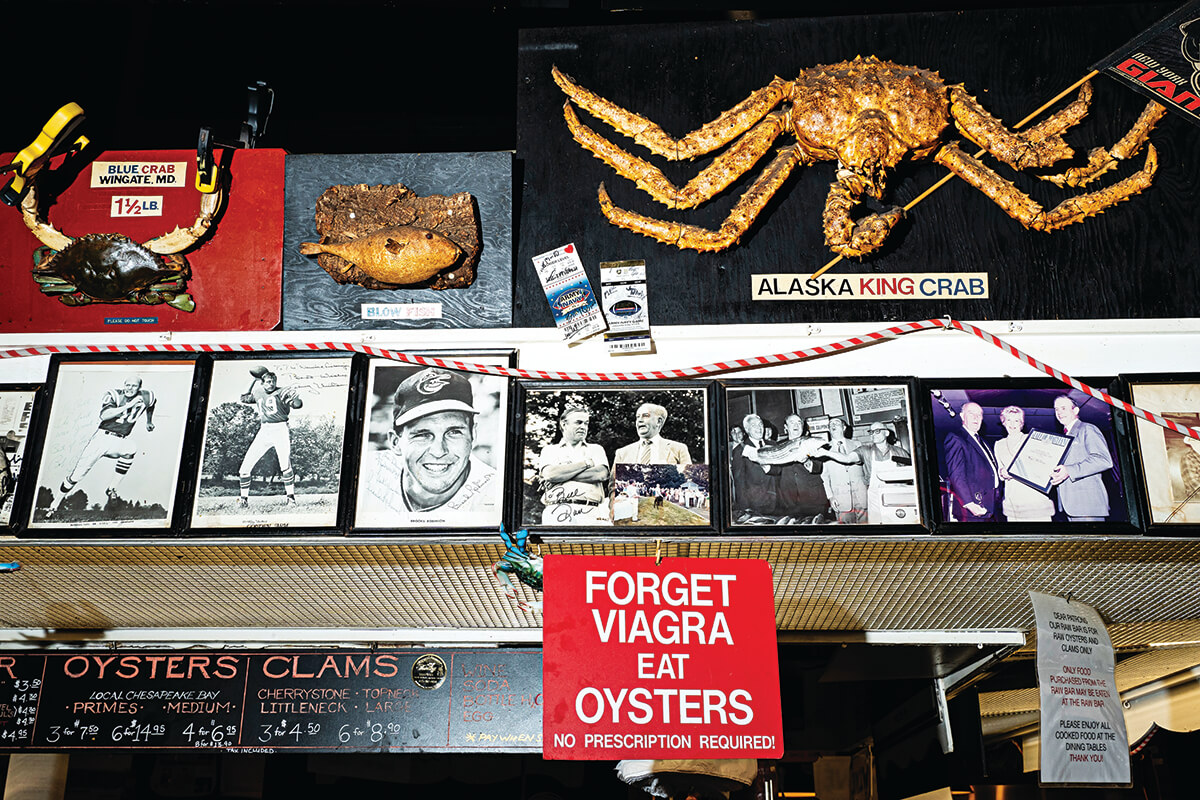

The future of Faidley’s, which for more than a century has been a fixture even as the fortunes of Lexington Market and the downtown neighborhood around it have risen and fallen, is about to change. In February, the city broke ground on Lexington’s $40-million South Market building, which will open in 18 to 24 months on what’s now a parking lot. Faidley’s, which will remain open in its current location during the construction, will eventually occupy a spot there, just about 200 feet from its current quarters. That a new building is needed is not in question; the infrastructure of the old one is crumbling. But whether that new building will be able to replicate the authenticity of the current one— where a chalkboard menu over the raw bar informing customers to “pay when served!” hangs below an autographed photo of Brooks Robinson, which hangs below a mounted blowfish—very much is.

“We don’t want to be a mall food court— we’re market people,” says the Devines’ daughter, Damye Hahn, who is also opening a Faidley’s outpost in Catonsville next year. She and her parents are determined to infuse the character and charm of their old home into their new ones.

“Anytime you have something new, there’s a possibility you’re going to lose something old, right?” says Jones, who drives to downtown from Dundalk two to three times a week. “But I doubt that the owners are gonna allow that to happen here. I really think it will retain its individual flavor.”

Above a sign on the raw bar that reads “Forget Viagra, Eat Oysters, No Prescription Required!,” is a poster touting “Smith & Faidley Sea Food and Game.”

“This is a part of the market to delight the epicure,” it reads. “Here one will find almost innumerable varieties of Fish, Game of all sorts, and Crabs, Oysters and Clams in season.”

That description of the business, which was started a staggering 134 years ago by John W. Faidley and a partner in two of Lexington Market’s wooden sheds, rings remarkably true today. (Faidley’s still sells muskrat and raccoon along with raw and prepared seafood.) As a young girl, Nancy remembers visiting her grandfather in his office.

“There were barrels everywhere, and it smelled like seafood, like being down on the water,” she says. “There was a lot of noise in the barrels because they were full of terrapin, an important product at that time. They made terrapin stew at all the finest restaurants.”

Eventually, John bought out his partner, shortened the name of the business, and later passed it down to Nancy’s father, also named John. While he ran it, she went to a local college to become a teacher. While there, she was set up with a naval officer from Kansas who was fresh off six months at sea.

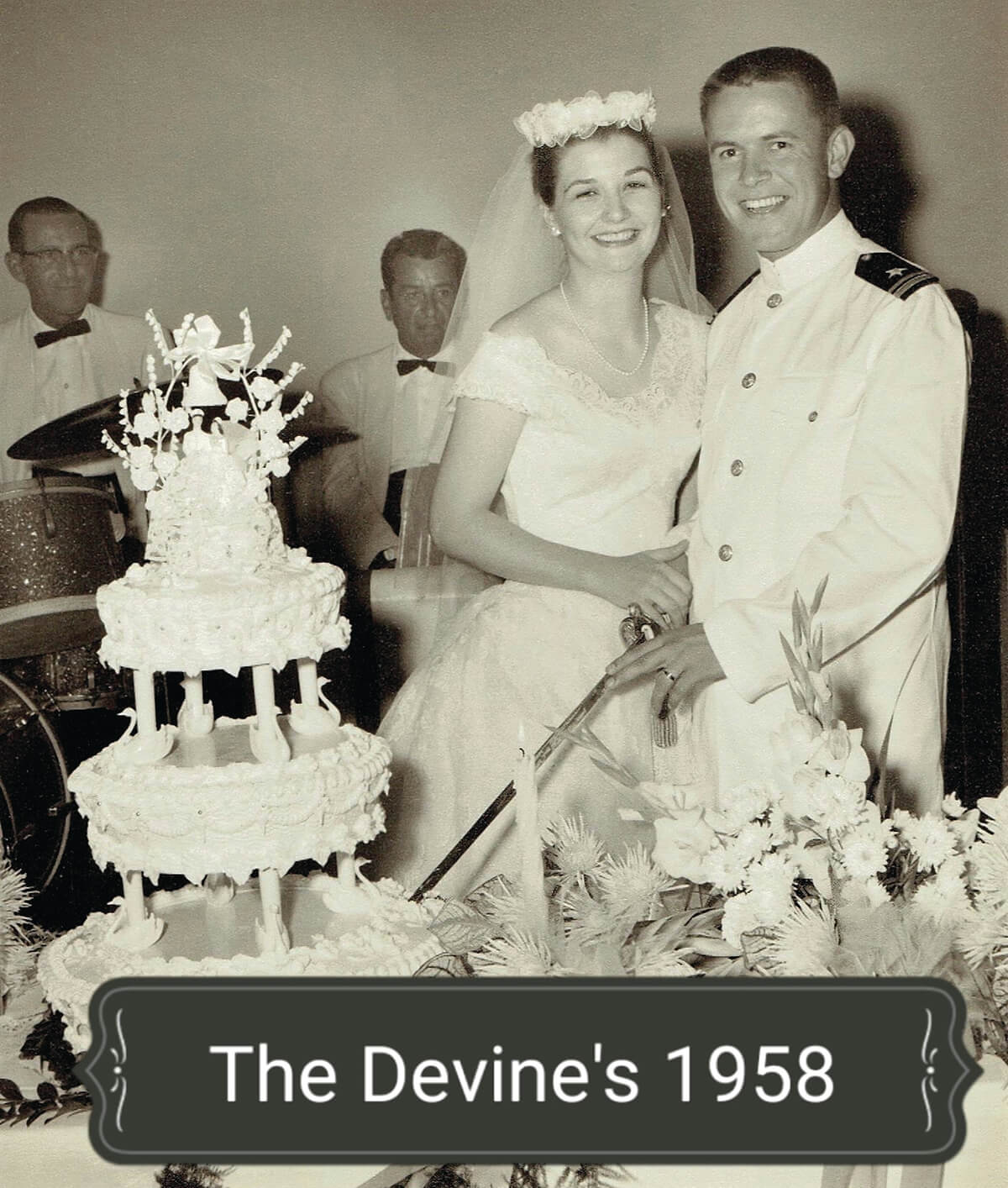

“The blind date was during a major snow in mid-March,” Bill Devine recalls. “There was a young man my age at the time helping Nancy’s father shovel the sidewalk. I had one rose walking up to her house. He said, ‘What are you doing here?’ I says, ‘I got a date with Nancy.’ He says, ‘Aw shit, I wanted to marry her.’ He set the shovel down and left.”

The date went so well that they decided to marry after only a few weeks together. Devine was deployed right after the engagement, and he didn’t return until days before the wedding in 1958.

“ANYTIME YOU HAVE SOMETHING NEW, THERE’S A POSSIBILITY YOU’RE GOING TO LOSE SOMETHING OLD, RIGHT?”

The couple soon moved to Virginia, where Nancy taught elementary school and Bill worked at the Pentagon. He started helping out on weekends at his father-in-law’s seafood market in 1964. “The idea for the communal tables came from the Pentagon,” Devine says. “At that time, on each corner on each floor, there was a cafeteria, but there wasn’t one chair in them, because if they seated those bureaucrats, they’d never get them back to work.”

Three years in the federal government turned out to be plenty for Bill, and the couple moved back to Baltimore to work full-time in the family business. Shortly before his death in 1990, Nancy’s father gave two-thirds of the business to her and one-third to Bill. (“I sleep with the owner,” he likes to quip with a wry smile.)

Faidley’s remained popular throughout the ’70s and ’80s, but it didn’t achieve food mecca status until Nancy started fiddling around with a new, all-lump crab cake recipe in 1987. At that time, Faidley’s sold a cake made with backfin meat and one made with claw that cost a buck. She created a mayonnaise-based sauce—the same one she uses today—because she thought it enhanced the crab without overpowering it. She didn’t want to put much bread in it, but because she sought the golden hue and crisp texture that frying provides, she needed a binder. Hence, the broken saltines.

“I made six crab cakes and the next day they were gone,” she says. “I had worried because it had to be a certain price point because the meat was a fortune, but it didn’t matter. People were willing to pay the price for the quality. It was outselling everything else I had.”

In 1992, GQ named the crab cake one of the best dishes of the year. That, along with the development of the internet and the onslaught of food-related programming on cable television, transformed Faidley’s from a popular local spot to a national and international destination. Governor William Donald Schaefer sent Nancy to Europe to promote Maryland, where she fed her famed crab cakes to the locals in Germany, England, and France. USA Today, Southern Living, and Gourmet tout- ed Nancy’s creation.

“Delicate, delicious, creamy and sweet, it may not quite be heaven, but by my reckoning it’s a persuasive preview,” wrote R.W. Apple Jr. in The New York Times.

Nowadays you’re almost as likely to eat one standing next to someone from the Brooklyn in New York as the one in Baltimore.

When Hahn opens the 22,000-square-foot location on Frederick Road in Catonsville, which will feature a sit-down restaurant (yes, you read that right), along with the familiar counter, carry-out, and retail services, her son, Will, will be heavily involved as well. He became the fifth generation to work for the company when he started shucking oysters as a teenager in Lexington Market.

But Faidley’s is a family business in more than the conventional sense of the term.

“WE DON’T WANT TO BE A MALL FOOD COURT—WE’RE MARKET PEOPLE.”

An astounding six sets of relatives work at the 3,500-square-foot original. Remel Watson has been there for 36 years. Her 23-year-old daughter, Donya Fleming, for five. Donya’s uncle, Lou, has worked there since 1979. He started selling fish, has shucked countless oysters (“My right hand is so strong, I could probably knock out Mike Tyson with one punch,” he says), and now is a manager.

“Me and Mr. Bill are close,” says Fleming. “I only spent 10 years with my dad, and I spent 40 with him. He taught me a lot about business and life. Do the right thing, work for what you want, and believe in your dreams.”

Donell Kindell, now 40, started at Faidley’s when he was 14. Ten years ago, Nancy chose him to become the only person other than her to make crab cakes. The promotion wasn’t quite as auspicious as it might seem.

“At the time, I had gotten in trouble,” says Kindell, whose father also works at Faidley’s. “To keep me from getting back into that same kind of trouble, she made me come make crab cakes next to her. I think that she saw that I was a good kid. I wasn’t a troublemaker. It was just something that happened that one time. As long as you’re honest with her, she’ll give you a second chance.”

Nancy doesn’t remember this story, but laughs when it’s recounted to her.

“Bill and I both feel that we’re better off giving people second chances,” she says. “Things happen in people’s lives. We know that. I also use it as a teaching opportunity for a lot of these young people who can learn from their mistakes so that they don’t make them again.”

Jamie Griffin started cutting lemons and pouring sodas for the Devines as a high schooler. Now, the 54-year-old’s daughter, Tiffani, works with him.

“My father died when I was small,” he says. “As I got older, Mr. Bill would ask me, ‘What are you going to do in life?’ When I went to buy my first house, I talked to him like you’d talk to your dad. I said, ‘Can you do me a favor? Can you hold money for me until the people ask for the closing costs?’ He actually [held] my money for me. I couldn’t spend it because he had it. When it was time to pay, I came to him, he wrote the check. He’s a boss, he’s a father, he’s a mentor. Miss Nancy’s the same way. And Damye.”

“You’ve got people from all over the world, people from all over Baltimore,” Hahn says. “All socio-economic groups, from the person that can only afford a codfish cake to the person that can afford anything they want.”

“People are comfortable with one another,” Nancy says. “We have the banker and the man that’s cleaning up the street, and it doesn’t make any difference.”

Ora Branch and her husband, Mike, who’s been coming for more than 30 years, made the 90-minute drive from their home in Southern Maryland on a Saturday in mid-February to stock up on fish. They arrived just before the lunch rush, but they weren’t here for crab cakes. Ora inspected black bass and rockfish by pushing her pointer finger into their scaly sides.

“When the fish is too soft, it’s not any good,” she says. “This was nice and firm, which means it’s fresh.”

Shanna Lowder took her first bite of a Maryland crab cake and couldn’t stop gushing as she declared it “amazing.” She has a friend back home in California who’s from Baltimore. He gets Faidley’s crab cakes shipped to him and freezes them. (The Devines overnight their cakes the day they’re made, using frozen gel packs to keep them cold.)

A semi-regular from Olney and his friend, a first timer from New Hampshire, leaned on the raw bar slurping oysters and clams. When they inquired about a particular beer, Griffin poured them a sample, unprompted.

“People from all over the country come here just because of Faidley’s, and we try to show them how hospitable Baltimore is,” says Hayward Pompey, who’s been a customer for 40 years. When a man asks about the plate of raw oysters topped with slivers of hardboiled egg and hot sauce in front of him, Pompey says they’re a Baltimore tradition and insists he try one.

Dody Brager is with her husband, their great niece, Jenn Harr, and their great-great- nephew. Nancy greets them like old friends, and as they move from the raw bar to the communal tables, they’re given a highchair that attaches to the table. The 16-month-old, Isaac, who nibbles tiny pieces of crab cake, is the only person at Faidley’s sitting.

Harrison Toms drove six hours from his home in Southern Virginia specifically for the lump cake—no toppings, no sides—that he’s currently savoring. “I know it sounds weird that someone would come that far for a restaurant, but you just can’t get it any better than this,” he says. “Too often people try to make a good thing better. Here they keep it the way it is. They don’t ruin what got them to the dance. I think that’s part of their success. They’ve been here forever, the idea works, and they’ve been smart enough not to change it.”

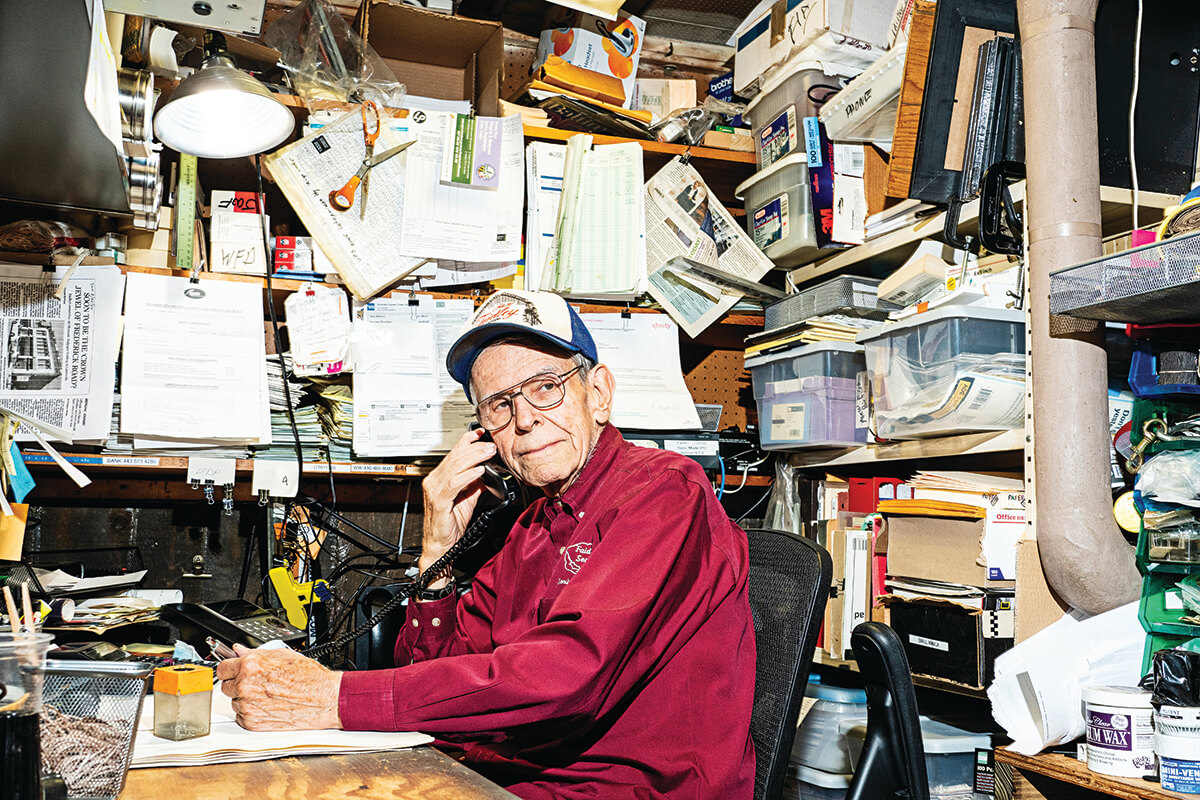

Both Nancy, 84, and 88-year-old Bill, who chews on unlit cigars and climbs a ladder to get to his eagle’s nest of an office that overlooks the market, come in four or five days a week. They continue to relish the work.

“People will say to me, ‘You’re not gonna retire, are you? What are we gonna do without this place here?’ That’s what kind of blows my mind,” Nancy says. “Why would I retire? When people come in here after not being here for five years and say, ‘Oh my god, it’s just the same,’ that’s what I want to hear. I want that experience that they had five years ago to be the same one they have tomorrow or 10 years from now. When the plates are empty, it’s like a pat on the back.”

Nancy still stands while making crab cakes. Her hands don’t tire, but her arms and shoulders do. It’s a miracle her back isn’t sore as well.