It’s no secret that Baltimore City has had its issues with rats. (We even have an acclaimed documentary and the satirical bumper stickers to prove it.) But when the rodents invade our dining spaces, the ironic affection turns to serious health concerns.

Last week, a video of a rat scurrying over pastries in a bakery showcase at Lexington Market went viral, eclipsing more than 800,000 views on Facebook in 48 hours. Four days later, another video showing a pair of furry creatures frolicking down the aisles at Northeast Market was posted on social media. Both markets, which are operated by the Baltimore Public Markets Corporation (BPMC), shut down voluntarily to evaluate the premises after the incidents occurred, and have since reopened.

“Sometimes doing business in downtown Baltimore can be tricky,” says Stacey Pack, marketing and communications manager for the BPMC. “We have active construction going on around Lexington Market at the moment. And anytime you have roads being dug up within a few blocks radius of a property, especially a food property, you’re going to attract things.”

Now, officials are coming together to improve the inspection system so that these issues become less frequent. Pack says that the BPMC works with a third-party pest control company that conducts preventative inspections weekly. But, in light of the recent infestations, the operations team plans to make that protocol even more aggressive.

She adds that the open communication between merchants and the community (both markets posted frequent updates to Facebook during the inspections) has been “key” throughout the past few days.

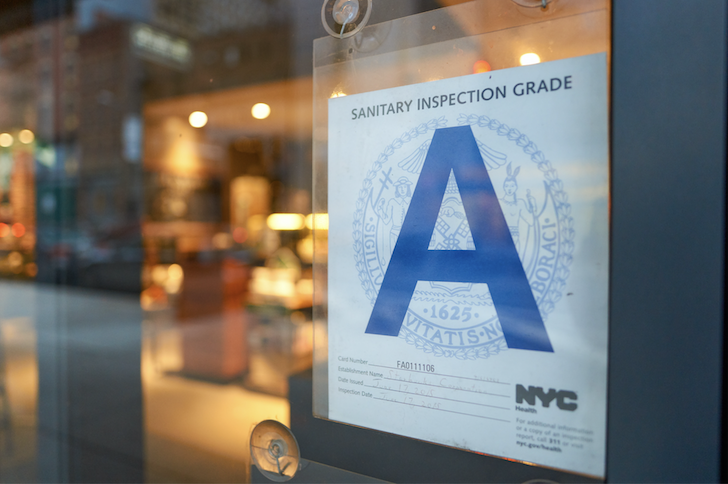

Transparency is something that Councilman Brandon Scott has been advocating for in the Baltimore City Health Department for years. In 2012, he introduced a bill to assign letter grades to food service facilities based on their inspection reports—a system enforced in many big cities including New York.

Though that original piece of legislation has since died, he is hopeful that a new bill requiring restaurants to post their latest inspection reports (which could potentially include the letter grades pending further amendments) visibly in their establishments will pass in some form by the end of this year.

“Folks are clamoring for that information to be more readily available,” says Scott, who was a major player in getting closure notices posted for the public to view online. “On a legislative side, we have to push progressive and bold policy to bring Baltimore in alignment with other major cities so that our citizens feel like they’re valued.”

Giving diners the freedom to choose where they eat based on visible health code reports has become a controversial issue among lawmakers and restaurant owners alike. Helmand Karzai, who owns four city eateries including The Helmand in Mt. Vernon and Tapas Teatro in Station North, admittedly has mixed feelings on the subject. While he supports posting reports for diners, he questions the need for a letter-grading system.

“I feel like it should be a pass-fail type of thing,” Karzai says. “Why would a restaurant even be open if it’s getting a ‘C’ or a ‘D’ and it didn’t fit the necessary guidelines? If it isn’t safe enough for the public, it should be closed.”

But Scott says that many of his constituents appreciate the autonomy that the visible grades have provided them while visiting other cities.

“The letter grades make the choice really easy for them,” he says. “And they feel like they should have the same thing at home. Things shouldn’t be in a cloud of secrecy like they have been for so long.”

Above all, Karzai—who says his restaurants receive unannounced inspections up to three times per year—stresses the importance of staff training and working together with Health Department officials to ensure better experiences for diners across the board.

“I wish there wasn’t so much animosity,” he says.“We’re all in this for the sake of food safety. If you talk to any restaurateur out there, they will tell you that food safety for your guests is always the top priority.”

That is certainly the case for Pack of Baltimore Public Markets, who says they have been “working around the clock” to address the health and sanitation issues.

“Public markets are so important when you think of community hubs and food access,” she says. “When it comes to food and public safety, you don’t mess around.”