Food & Drink

The Iconic G&A Restaurant Moves Its Hot Dogs to New Digs

After almost a century in Highlandtown, G&A relocates to White Marsh.

During its final days in Highlandtown, after being in the same location for almost a century, G&A Restaurant was packed with customers craving the eatery’s signature Coney Island hot dogs—plump franks smothered with yellow mustard, homemade chili sauce, and chopped onions, piled into soft buns. Longtime diners realized that when the doors closed for good in mid-July, they would have to wait until September for another taste of the popular wieners at G&A’s new home in White Marsh.

There, the nonstop hot-dog banter will once again bellow throughout the dining room: “Six up,” meaning six dogs with all the condiments. “Two up, hold the mustard.” “Four up, no onions.” It’s kitchen speak for how the dogs are prepared.

As he’s done for years, G&A owner Andrew “Andy” Farantos will preside over the rapid-speed exchanges with his servers like an auctioneer taking bids, lining up the rolls, often along his arm, and applying the appropriate toppings in rapid succession to get them to diners quickly. He’s a 55-year-old, third-generation proprietor who started working at G&A when he was a kid, peeling potatoes and sweeping the floors before taking over the family hot-dog business in 1988.

“I’ve eaten thousands of chili dogs there,” says customer and occasional Baltimore contributor Rafael Alvarez, who lives in Greektown and frequented the original G&A for about 30 years, slightly exaggerating. He refuses to call the restaurant’s main dish by its official name. “I hate the Yankees, and I’m not going to say Coney Island,” he insists.

When in operation, G&A on Eastern Avenue was full of characters, and some will be left behind when the restaurant moves to Honeygo Square shopping center on Philadelphia Road in Baltimore County this fall. It wasn’t an easy decision for Farantos and his wife, Alexia, to relocate. It took Andy more than a year to make a commitment and sign the lease, Alexia says.

“There were more customers coming from there,” explains Andy Farantos about the G&A visitors from Perry Hall, Harford County, and beyond who traveled to Highlandtown. “We’re going to do what we’ve been doing for 90-plus years and do it there.”

Alexia Farantos, who is a smiling presence at the restaurant, seating customers, waiting tables, and keeping track of the paperwork, has mixed feelings.

“It’s so sad. Some people don’t have transportation [to get to White Marsh],” she says. “It breaks my heart.”

“WE’RE GOING TO DO WHAT WE’VE BEEN DOING FOR 90-PLUS YEARS AND DO IT THERE.”

White-haired Ken Sears, who has been a G&A staple for 20 years, is one of the diners who will be unable to make the trek. Before the restaurant closed, he sat at one of the booths, leaning on a well-worn, green Formica table where hundreds of elbows have preceded him, preparing to place his usual order: two eggs with home fries and toast. “This is my favorite place in Highlandtown,” he says. “I’m not happy they’re moving. I don’t know any place to replace it.”

After learning that G&A was moving to White Marsh, Alvarez was dismayed. “It’s a sacrilege,” he says. “I’m heartbroken.” But he’s accepted the reality of the relocation and says he will visit, “reluctantly, but I will.”

The upside for the Farantoses is that the new place is close to their Perry Hall home, easing the commute after years of long hours on the job. Alexia also points out that she and her husband didn’t own the 1910 building that housed G&A. “The family has been paying rent since the late ’60s,” she says. “It doesn’t make sense.”

The couple is still deciding on the décor for the White Marsh restaurant, though they are excited they will have outdoor seating. They also plan to bring many of the photos that lined the old restaurant walls, which include a vintage 1930 Ocean City boardwalk scene, another showing long-ago workers from the defunct German restaurant Eichenkranz eating steamed crabs, plus shots of celebs like Henry Winkler as The Fonz and a moody James Dean.

Like many other restaurants, G&A suffered financially during the pandemic, but Andy and Alexia began planning the move two years ago, before COVID-19. For the past year and a half, they had to let staff go until they could get back on their feet. Andy did most of the cooking; Alexia was the only waitress at times.

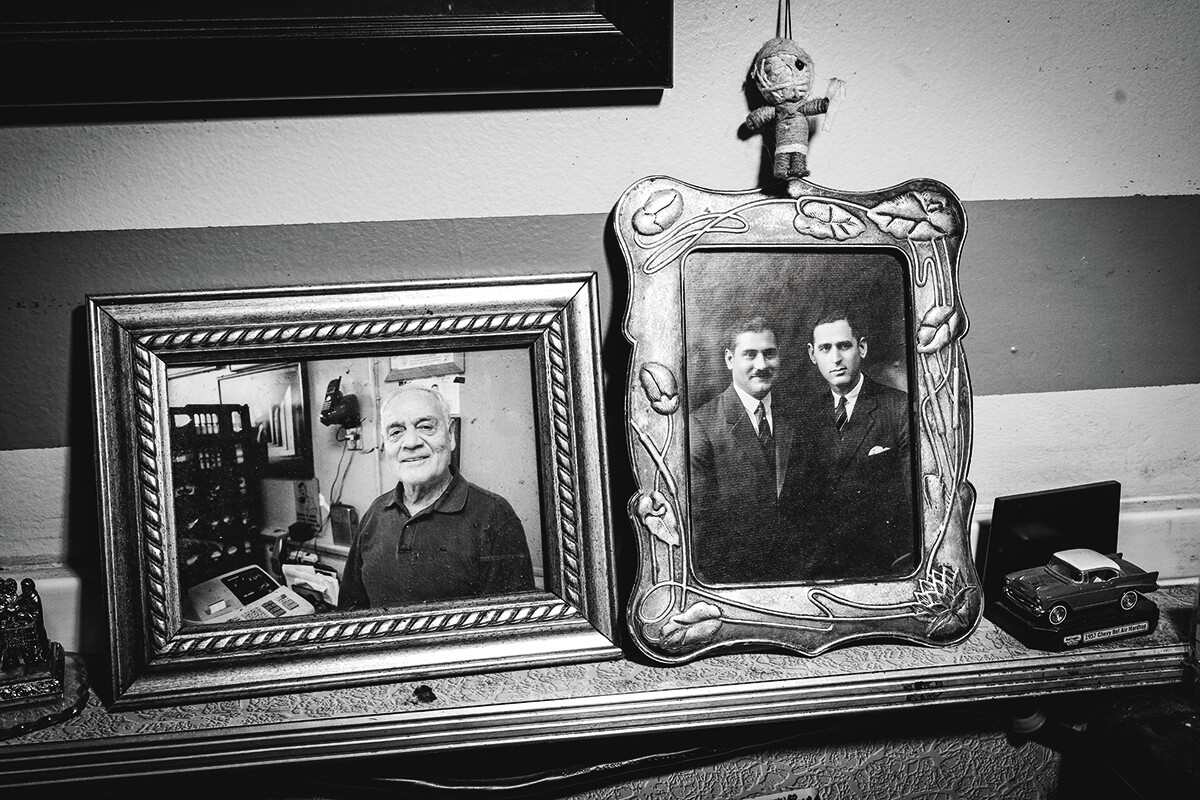

The couple is now about to embark on a new chapter of an American dream that started in 1927 when two Greek immigrants from Sparta started selling Coney Island dogs for 15 cents in the up-and-coming Southeast Baltimore neighborhood of Highlandtown. (Recently, the Coney dog was $3.) Ancestry.com records indicate Grigorios (who Americanized his name to Gregory) Diacumakos (Andy’s great-uncle) and his cousin Alexios “Alex” Diacumakos arrived in New York and lived in Pennsylvania before settling in Baltimore and opening a hot-dog stand. They used the initials of their first names to christen their venture G&A. A framed photo of the two men, dressed in suits and ties, overlooked the cash register in Highlandtown, almost like guardian angels keeping watch on the family. It will also grace the White Marsh store.

By the 1930 census, about 2,000 people with Greek heritage lived in Baltimore, and about a fourth of them gravitated toward Highlandtown, according to a 1938 Baltimore Sun story. The influx continued. In a 1970 story, The Sun reported that about 18,000 Greeks made Baltimore their home. In the article, the Rev. Peter Chrisafideis, pastor of St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church on Ponca Street, said the new immigrants headed to Highlandtown to adjust to American life because of the Greek community there.

Besides the Greeks, the growing community of Highlandtown was a mix of Germans, Poles, Slovaks, Italians, and Finns. Today, you can add African Americans, Latinos, and other nationalities to the mix.

So why hot dogs for the Diacumakos cousins? In the 1900s and 1910s, the Coney dog was spread across the eastern United States by various Greek immigrants who migrated because of their country’s economic woes, according to a 2016 article in Smithsonian Magazine. Authors Katherine Yung and Joe Grimm posited in their 2012 book Coney Detroit: “Many of them passed through New York’s Ellis Island and heard about or visited Coney Island, later borrowing this name for their hot dogs, according to one legend….Why they took a fancy to this food remains a mystery.”

In his blog, Food Passages: Excursions in the World of Food and Culture, Joel Denker surmises that the Greek immigrants chose hot dogs because they were a quick and cheap food and would appeal to a growing urban workforce looking for inexpensive meals. He quotes food historian Bruce Kraig: “People came with no money at all….Say we’re talking about 1900, you could buy a sausage for a penny and the other accoutrements for a penny, and you sell it for a nickel. And that’s the way you move up in the world.”

Baltimore also latched onto the sandwich. The Sun proclaimed in a 1927 blurb: “In these days, evolution is plainest marked by the change from the cold chicken sandwich to the Coney Island hot dog for luncheon,” making

the Diacumakoses early-day trendsetters.

FOR YEARS, G&A WAS OPEN TILL THE WEE HOURS OF THE MORNING TO ACCOMMODATE SHIFT EMPLOYEES AND LATE-NIGHT REVELERS.

In 1933, as Prohibition ended, the cousins applied for a license to “sell beer and other beverages of alcoholic content,” according to a Sun article. In the meantime, Highlandtown was becoming a destination with its very own Easter promenade on Eastern Avenue; an Epstein’s department store, which attracted throngs of thrifty shoppers who could buy items ranging from floral house-coats to odd-size curtains; and numerous taverns to quench the thirst of workers from the nearby steel mills, packing plants, and breweries.

For years, G&A was open till the wee hours of the morning to accommodate shift employees and late-night revelers. The hours are yet to be determined for the White Marsh location.

It was a tightly knit, caring community. Alvarez recalls a story that his Uncle Albert told him about G&A. It was 1943, and Albert, who was 18 at the time, was waiting for a bus in front of the restaurant around 6:30 in the morning. He was heading to the Fifth Regiment Armory in midtown Baltimore to enlist. When Alex Diacumakos found out where Albert was headed, he invited him inside the restaurant for a hearty plate of eggs, bacon, and toast on the house. Diacumakos’ parting words were: “Come back safe.” And he did.

By 1966, Andy Farantos’ father, James “Little Jimmy” Farantos, and his uncle, James “Big Jimmy” Mexis, were running G&A. Over the years, the menu expanded to include diner dishes such as hot turkey platters, Greek salads, and grilled cheese sandwiches.

When Andy took over in 1988, he added items like crab cakes, shrimp salad, and beef brisket. Another milestone event happened that year: He and Alexia became engaged. They seemed destined to meet and start a life together.

Andy was born in Virginia, but the family soon moved to Greektown before eventually settling in Timonium. Alexia spent her early years living near Greektown. Her father, Jimmy Meligakos, ran Kozy Kitchen, an old-time diner on Ridgely Street not far from where Horseshoe Casino stands. She often helped out on Saturdays, washing dishes in a three-section sink and making “half-and-half drinks” (half iced tea and half lemonade, generally called an Arnold Palmer today) for customers. Her dad would often take her to G&A when she was a little girl while her mom was shopping on “The Avenue,” as Eastern Avenue was called then.

The couple was introduced briefly on the campus of what was then Essex Community College by a friend and went their separate ways. Andy attended the University of Maryland as a business major. Alexia was working at Milano’s restaurant in Pikesville when one of the business’ silent partners visited. Surprised, she blurted out, “That’s the hot-dog man!” It was Jimmy Farantos, Andy’s dad and, though she didn’t know it at the time, her future father-in-law.

When Alexia was transferred to the Milano’s in Timonium, Andy, who had worked at various restaurants in Baltimore and Ocean City over the years, was making the pizza there. He immediately told her, “I’m going to marry you one day.” After a first date on New Year’s Eve, they tied the knot in 1989 at the Greek Orthodox Cathedral of the Annunciation on West Preston Street. “She is a sweetheart,” Andy says of his bride of 32 years.

Andy and Alexia have three children, who are in their 20s. Their eldest daughter, Anna MacCuish, recently opened a brunch spot, Easy Like Sunday, in Charlotte, North Carolina, with her husband, Sean, following in her family’s food footsteps. She also gave birth to her parents’ first grandchild, Kingston Andrew, on Dec. 1, 2020. Another daughter, Demi, is a graphic design artist, and son Dimitri is an R.N.

Alexia didn’t start working regularly at G&A until about 18 years ago. Dimitri was born with a blood disorder, a condition called sickle beta thalassemia, and she needed to spend time with him in the hospital when he was younger. Then one day, she went to G&A to help out, and “I got stuck,” she says with a laugh.

Over the years, the neighborhood has changed, Andy says. Epstein’s folded in 1991, Bethlehem Steel shut down, and Westinghouse and General Motors closed. The list went on. Drugs were also an issue. “The area became rough from about 1992 to 1999,” he says. “I became particular [about] who came in here. Then, Canton revived it.”

Gerry Pecora remembers when customers stood in line to get a seat at one of the 14 counter stools and 17 booths in the narrow, storefront restaurant. She grew up in Highlandtown, and even though she lives in Dundalk now, she returned to G&A every five weeks with her husband, John, whenever they went to the nearby salon Hair Setters.

On their visits, John would order one of the breakfast plates, which are served all day, leaning toward fried eggs with scrapple or an omelet. Gerry would get a Coney dog or burger, splurging on fries occasionally. “It’s the family atmosphere,” she says about the restaurant’s draw. “I have good memories of my childhood when I come back.” She’s sorry the restaurant is relocating but adds, “I think it’s a good thing. We’ll go.”

Andy Farantos recalls the restaurant’s heydays, when bigwigs like Dominic “Mimi” DiPietro, a beloved East Baltimore City councilman who was dubbed the unofficial “mayor of Highlandtown”; Orioles owner Peter Angelos; and H&S Bakery magnate John Paterakis graced G&A’s red-and-chrome counter stools, talking to panhandlers and church ladies alike. It was a welcoming place. “My family is in the hospitality business,” Andy says. “We say it with pride: ‘It’s a great little hole in the wall.’”

One of the highlights in recent years was a visit from Guy Fieri in 2008 to film an episode of Food Network’s Diners, Drive-Ins and Dives. A poster-size photo of Fieri hung prominently on a wall to remind customers of the show. In true fashion, Fieri pulled up to G&A in his flashy 1967 red Camaro convertible on a sunny March day for the taping. Andy laughs at the memory. Fieri had to drive around the block three times in busy traffic because he kept flubbing the Diacumakos name in his introductory spiel as he got out of the car.

Once inside, it was showtime. Andy took Fieri into the small kitchen in the back to put together the beanless chili he layers on the Coney dogs and other menu items, including a Coney omelet with, yes, hot dogs. It’s a daily ritual. Andy mixes ground beef from local Old Line Custom Meat Co., paprika, chili powder, celery salt, and other “secret spices.” Fieri called the thick mix a “crazy meat concoction.” When asked for more particulars about his chili recipe, Andy will only confirm that he makes it with “just love.”

The show brought G&A a lot of local and national attention. Regular customers like Alvarez weren’t surprised but puzzled by the newfound interest. “Now they have cred?” Alvarez asks. “They’ve always had cred.”

Soon, that “cred” will be making its way to the ’burbs.

A Crash Course on Coney Dogs

You’re forgiven if you think Coney Island hot dogs originated at Coney Island, the amusement park in New York.

They didn’t, despite the name. It’s true that Brooklyn’s Coney Island is credited as being the birthplace of the American hot dog on a bun, thought to have been first sold by a pie-wagon vendor named Charles Feltman as early as 1867; then, by Nathan Handwerker, a Polish immigrant who worked for Feltman and opened his own place in 1916.

Nathan’s Famous restaurants live on today, as does Nathan’s Hot Dog Eating Contest, held every July 4. But the Coney Island hot dog—a beef frank layered with onions, mustard, and chili minus the beans on a steamed bun—has a different beginning, one that involved Greek immigrants coming to America at the turn of the last century. At that time, about 343,000 people migrated from the southeastern European islands.

Many Greeks came through Ellis Island in New York and probably heard about Coney Island, borrowing the name for their version of the hot dog, wrote Katherine Yung and Joe Grimm in their 2012 book Coney Detroit. The expanding auto industry in Detroit was a draw for many immigrants to the Midwest. But opening restaurants dedicated to Coney Island dogs was also a financial incentive for the Greek entrepreneurs who dressed their dogs in variations of saltsa kima, a popular Greek ground-beef topping, according to a 2016 Smithsonian Magazine article. Jane and Michael Stern described the chili this way in their book 500 Things to Eat Before It’s Too Late: “The Coney Island’s formidable beef topping with a sweet-hot twang has a marked Greek accent.”

While no one is sure who originally came up with the Coney Island hot dog, the Coney Detroit authors say: “It appears that several Greek immigrants all started selling Coney dogs in the early part of the 20th century, not just in Michigan but also Massachusetts, Florida, Texas, and other states.” And that includes Maryland, where two Greek immigrant cousins opened G&A Restaurant in 1927 in Baltimore to sell their take on Coney Island hot dogs.