Rebel With a Cause

James Beard Award-winning chef Spike Gjerde digs deep.

Spike with his team.

The day he graduated from Middlebury College, Spike Gjerde, a lifelong lover of pranks, staged his pièce de résistance in front of the Old Chapel administration building. In the wee hours of the morning, Gjerde and a friend scrambled up a towering tree, leapt onto the building’s deeply pitched slate roof, strung ropes around the historic clock tower, and made their way down, at one point dangling about 20 feet away from the head of a security guard. Their denouement? “We attached two Mickey Mouse hands to the clock hands that we’d made out of plywood,” Gjerde recalls, still smiling at the memory. “And behind it, we attached a Mickey Mouse head—it was a full-on Mickey Mouse watch.” While Gjerde and his friend were never linked to their act of derring-do, it created quite the stir. “People were taking pictures and talking about it,” he says. “I was really proud of it. On some level it was a commentary on whatever interaction I had had with the administration as a student there.”

Thirty years later, “daredevil mastermind” is not the first phrase that springs to mind when one envisions Gjerde, the now-53-year-old winner of the prestigious James Beard Award and chef/co-owner of Foodshed restaurant group (a.k.a. the company that includes Woodberry Kitchen, Parts & Labor, Grand Cru, and Artifact). But truth be told, Gjerde has a rebel spirit that runs rampant beneath his plaid shirt, his penchant for deep thought combining with a mischievous mien to make him one part Rodin’s Thinker and one part Peck’s Bad Boy. “When I met him, he was like no one I’d ever met,” says Amy, his business partner and wife of 17 years. “He seemed larger than life. He gets satisfaction from bumping up against the norm—he doesn’t accept things as they are.”

In fact, it’s his love of risky business that has helped him become one of the most important chefs in the Mid-Atlantic, changing not only the way we eat,

but even the way we think about food. “There’s a lot of what Woodberry is about in that story,” says Gjerde, reflecting on his youthful antics. “We’re very

serious in our

approach to food and thinking about it, but we also like to have a lot of fun with it.”

The chef in a quiet moment at Woodberry.

In many ways, 2015 was the culmination of Gjerde’s career. Last May, when the city was reeling from Freddie Gray’s death, Gjerde became the first chef in Baltimore to take home the James Beard Award for Best Chef: Mid-Atlantic. “There are very talented people in Philadelphia and there are incredible things happening in D.C.,” says Gjerde, resting his head in his hands, as is his habit. “I felt like if I didn’t win that year, I might not ever win.” But he had a hunch he might. “I felt that Woodberry had never been better,” he says. “When Woodberry started, it evolved. I really feel like, I didn’t do a great job with it in the middle years. I don’t think that Woodberry was the restaurant that it could have been or should have been after it got opened. I just didn’t have a clear sense of what I was trying to do.”

And though the past year was full of highs, he’s the first to admit that it was also tempered by lows. “I don’t want anyone to think this is easy,” he says. “There have been some tough moments that have also been connected with the best moments. That’s the nature of the business—as soon as you feel you’re on top of the world, someone will come and knock you down.” Mere weeks after his win, Gjerde’s Shoo-Fly diner closed in Belvedere Square after tepid reviews (there were also earlier issues with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration over “a lack of clarity with Maryland State and Baltimore City authorities” over canning, he says), and, a month later, the news came out that some employees were suing over alleged unfair wage practices at Woodberry Kitchen. While the case is still pending, he will say, “We’re working through it. It’s a process. It’s not fun. There are other well-known chefs who have dealt with this, too.”

Despite the rollercoaster ride, Gjerde is more focused than ever on staying true to his local sourcing mission. On a raw winter’s day, as on many days, Gjerde can be found at Foodshed, a stone’s throw from Woodberry Kitchen in the Clipper Mill Complex—his home away from his Roland Park home. The office is Command Central for his expanding enterprise, which will soon include his first non-Baltimore restaurant, still to be named, inside The Line in the Adams Morgan neighborhood of Washington, D.C. (“We’ll take the Woodberry approach, but our gaze will shift to Virginia, an incredible agricultural region with its own traditions,” he notes.) Also in the works, a sibling restaurant to Artifact in Charles Village.

As he sits in a mid-century modern leather chair, a gift from Amy, he’s surrounded by shelves of cookbooks (among them, his favorite, food writer Richard Olney’s Simple French Food, which brings him to tears as he reads a particular passage), photographs of his children Katie, 13, and Finn, 16, and various bric-a-brac, including a jar of dried lovage that belonged to his late father, David, an avid container farmer. “Restaurants open all the time,” he says. “But what we’re doing is, I don’t even know what to call it. . . .,” he says, sounding truly perplexed.

“There have been some tough moments that are also connected with the best moments.”

It’s safe to say that Foodshed is certainly in its own category when it comes to so-called “farm-to-table” cuisine. “When I started Woodberry, I had a five-page list of pantry items that I would order from a distributor,” explains Gjerde. “Things like capers and olives and olive oil and flour and Worcestershire sauce—now that page is a half-page long.” And that’s because he now makes all those items himself.

While most farm-to-table spots in Baltimore give lip service to local sourcing with an heirloom tomato here, or a homegrown head of cauliflower there, Gjerde approaches the term with messianic zeal. To date, he has systematically eliminated scores of pantry staples for ingredients that can be found locally. He practices a sort of culinary vérité, in which lemons and limes have been replaced by verjus; olive oil has been supplanted with herb-infused canola oil derived from locally pressed seeds; mustard seed and paprika peppers are purchased from organic farms in Southern Maryland. Even Tabasco sauce has been swapped for Gjerde’s spicy Snake Oil, whose main ingredient is the fish pepper—once widely used in Chesapeake cuisine, but which fell into near-extinction more than a century ago until Gjerde asked his growers to plant it. “Every time we get something figured out, we add a layer of additional complication that makes it even more challenging,” he says. “One of our mantras at Woodberry is that there has to be a harder way.”

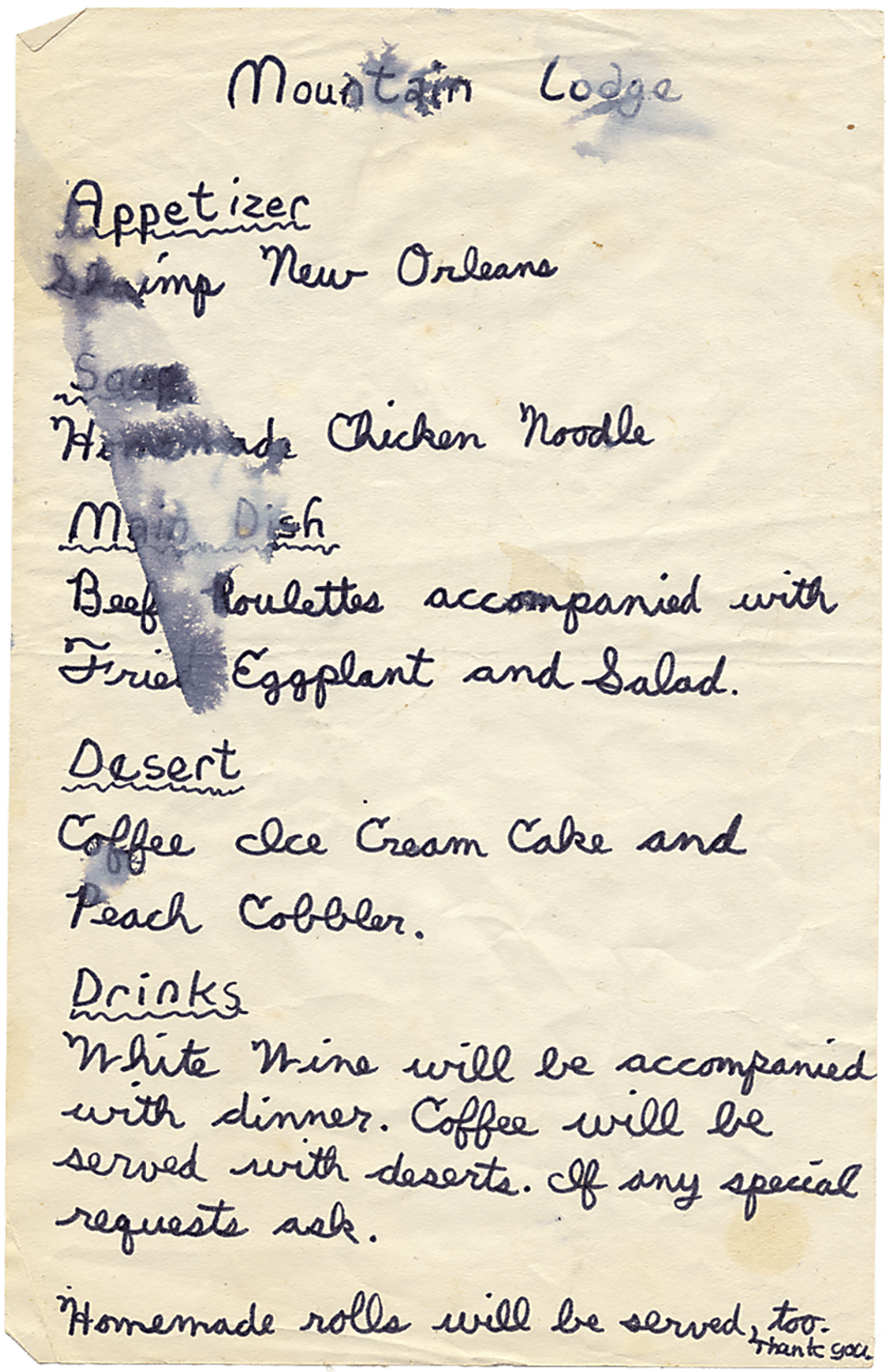

If there’s a leitmotif in Gjerde’s life, it’s that he has never taken the easy way out. In the early years that meant that when other kids in his Cockeysville ’hood played cops and robbers, he and his younger brother, Charlie, played “restaurant,” creating handwritten menus and real food that they sold back to their parents. “I remember one of our restaurants was called The Lakeview Inn,” he says. “On our menu, we actually gave choices,” recalls Charlie. “Our parents probably went out to eat afterward, but it was the real deal.”

Pushing himself didn’t stop there. At Middlebury in Vermont, the philosophy major minored in Mandarin, because, he says, “it was a way for me to test myself. I literally picked it because I couldn’t imagine anything harder.” (“Our kids hate it when he breaks out in Chinese,” says Amy, laughing, “but if we go somewhere like Chinatown in New York City, he’ll speak it.”) And while other students made microwave popcorn during college, Gjerde served pâte à choux pastries during dinner parties in his dorm room. At the same time, he worked at a local Vermont bakery—Knave of Hearts—surviving on little sleep and bribing his teachers with bread. “I felt something when I went to this bakery,” he says. “I was bowled over by what they were doing. It took me weeks to get the nerve up to ask for a job.” Those New England years, which also included a summer spent on a dairy farm after graduation, sowed the seeds for what was to come. “I fed the cows,” Gjerde recalls. “I bailed hay. I had this moment when I was walking along the road and a car was racing by. I was just this sunburned kid in a white T-shirt and jeans and those boots that we wore on the farm. I thought, ‘To those tourists, I’m part of this landscape.’ That meant a lot to me.”

After college, by the late ’80s, Gjerde was back in Baltimore, soul-searching and struggling to figure out how he could fit into the local landscape. Like his late mother, Alice, who loved to experiment in the kitchen (and whose Gourmet magazines are decoupaged on the walls at Woodberry Kitchen), cooking continued to call to him. One day, while wandering down East Baltimore Street, he walked into a new pastry shop, Pâtisserie Poupon. “They had apricot tarts and things I’d never seen before,” he remembers. Gjerde was hired for $5 an hour to work with the owner Joseph Poupon and his wife, Ruth. (And they remain friends to this day.) “The first time I got to assemble the fruit tart with almond crème baked into it and then various fruits with an apricot glaze, you would have thought I had a painting in the Louvre,” he says.

In 1991, with zero restaurant experience other than their fictional childhood restaurants, Spike (né David, like his dad, until some friends nicknamed him Spike) and his brother, Charlie, a then manager at LensCrafters, decided to take a chance and opened up their own spot, Spike & Charlie’s in Mt. Vernon.

At a time when most chefs were sourcing from big suppliers and distributors, Gjerde, who has always done things differently, went directly to the source. “I started going to the farmers’ markets that we still go to today—the Waverly Market and the JFX Sunday market,” he says. “First, I started buying bags of stuff, then a backseat full of stuff.” It was then that he realized the challenges of local sourcing. “I took what I had purchased to the restaurants and tried to figure out what to do with it,” he says. “I wasn’t saying, ‘My whim is that I want to cook with snap peas in February.’ I was like, ‘I’ve got this incredible kale. Now I’m going to figure out something to do with it.’”

Joan Norman, co-owner of White Hall’s One Straw Farm, who has worked with Gjerde for more than 25 years, recalls eating one of those farm-fresh meals at Spike & Charlie’s. “If something is the best thing you ever ate, you remember where you were, whom you were with, and what you ate,” she says. “This soup came out and it was butternut squash with wild rice croutons. And he’d made it from our squash—I’d never had that happen before, selling something to a chef, and then walking into a restaurant and having something that we had grown.”

“Our mantra at Woodberry is that there has to be a harder way.”

In the ensuing years, the brothers continued to open spots—Jr., Vespa, Atlantic, Joy America Café—but by 2004, when Charlie decided to take a break from the business, and the restaurants fell on hard times in the aftermath of 9/11, they decided to call it quits. “Amy and I weren’t in a good place financially,” recalls Gjerde. “And I wasn’t exactly a hot commodity. We had gone from this peak in the 2000s with multiple restaurants to struggling to pay bills.” The couple contemplated leaving town, too. “Amy and I were doubtful that we could find a fit in Baltimore,” he says. “We talked about going somewhere else—but we didn’t know what, and we didn’t know where.”

Instead, in 2006, when developer Bill Struever approached the couple about opening a restaurant in an 1850s machine manufacturing shop in Woodberry—an area of town that few knew at the time—they decided to take a chance. “There wasn’t even a road there,” says Gjerde. “It was just dirt. It was the middle of nowhere.” And though farm-to-table was not yet a part of the local lexicon, Gjerde was fleshing out his idea. “The vision was to wipe away everything else and buy what we could from local farmers,” he says. In fact, Gjerde knew so little at the time that he hadn’t given thought to basic contingencies. “He came to my farm while he was building Woodberry,” recalls Norman, “and he said, ‘I’m going to have this farm-to-table restaurant,’ and I said, ‘How big is your freezer?’” Admits Gjerde, “I thought I was too good for freezers. I had this relatively small freezer. In preparation for the winter ahead in ’08, we bought 10 cases of Roma tomatoes and red peppers from Joan. Six weeks later, we were out of everything.”

Spike Gjerde stores his James Beard Award in his knife box.

A childhood menu designed by Spike and his brother, Charlie.

Two years later, he purchased a large freezer. And ever since those days he has toiled tirelessly to tweak and refine his concept. Canningshed, his preservation operation that canned 57,000 pounds of local produce during the last growing season, is the result of those lessons learned from that first winter when he was forced to import produce from Florida. It’s a number that includes 25,000 pounds of tomatoes, 8,000 pounds of berries for jams, and 2,650 pounds of cabbage for sauerkraut. And while cooking is still a strong passion—in fact, he’s “on the line” at Woodberry some Tuesday nights—the cerebral chef also offers food for thought with events such as one at Artifact Coffee featuring people on the local scene from cheesemakers to vintners to experts on seafood sustainability. “Spike has been a leader in creating awareness into the resources available and in danger in the Chesapeake watershed,” says Bryan Voltaggio of Aggio and Family Meal. “His commitment is admirable.”

It’s late January and, within the next month, Gjerde will meet with a dozen or so of his principal growers to hash out the details for the coming growing season. While most restaurateurs order their inventories online from multinational suppliers such as Sysco, in Gjerde’s world, deals are done over a freshly brewed pot of Chemex coffee and just-baked huckleberry sour-cream coffee cake in the inner sanctum at Foodshed. On this day’s agenda is a planning meeting with organic farmer Heinz Thomet and his wife, Gabrielle Lajoie, of Next Step Produce in Newburg. Sitting around a large reclaimed table with whole-wheat bread made from Thomet’s stone-milled flour, the get-together includes Thomet’s three girls, ages 9 to 13, and feels more like a gathering of friends than a business meeting. In the course of conversation, decisions are made on the planting of crops—among them rice, wheat, and strawberries—that will find their way onto Foodshed’s menus. “The produce writes the menu,” says Gjerde to the group that also includes David Speegle, his chef de cuisine at Artifact and Patrick “Opie” Crooks, his chef de cuisine at Woodberry. “My job is to respect the ingredients and connect them back to the farmers.” It’s a model that has not only put $2 million back in the pockets of growers and wine makers, but one that sits well with his chefs, too. “I was working at Roy’s and hit a wall,” says Speegle. “I was ready to stop cooking and start farming. I was frustrated working with the product I was given. Most chefs who want to work seasonally think there are four seasons. Spike recognizes that seasonal cooking is actually 52 weeks a year.”

Refusing to rest on his laurels, Gjerde continues to raise his own bar. His latest project is an attempt to replace organic sugar with ingredients such as sorghum and maple, difficult to do when you’re in the pastry-making business. With his James Beard medal slung haphazardly across the handle of his portable knife box, he still dreams of how to keep pushing himself to the limit, how to make things harder. “With Spike, it’s more about the mountain than being at its peak,” says Norman. The Beard Award has served as further fuel. “In the culinary [world], winning the award is one possible moment you’ll get to arrive at,” says Gjerde. “It’s not the only one, but for me and my path, it was meaningful. But then you’ve got to just keep going.”