Food & Drink

Spice of Life

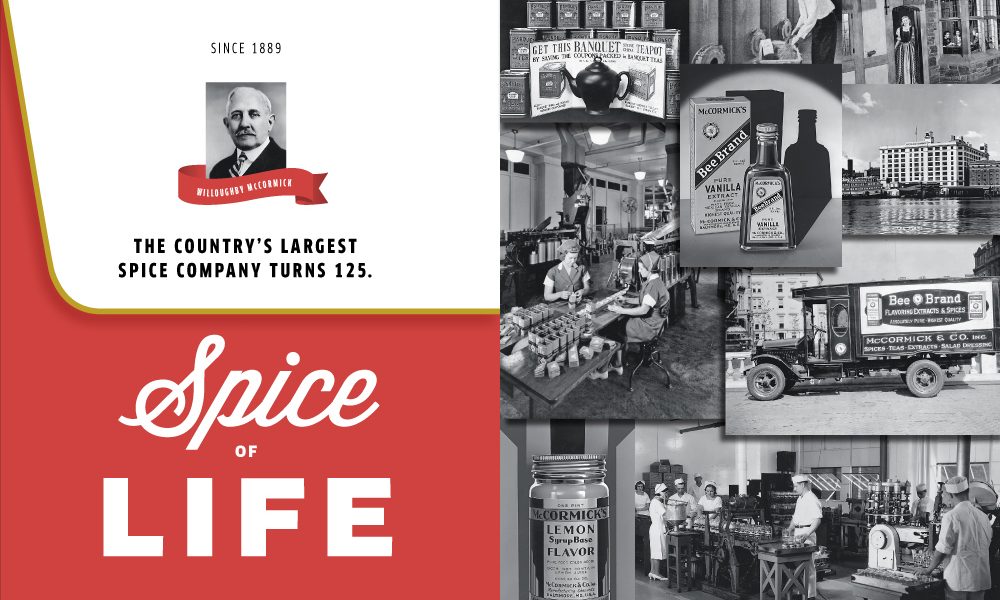

The country's largest spice company turns 125.

Back in the early 1960s, the folks at McCormick & Company were sure they had a hit on their hands. The homegrown spice and flavoring giant was launching a powdered, effervescent, children’s drink in foil packs they cleverly called “Fun.”

Charles “Buzz” McCormick Jr. was a company product manager at the time (he retired as CEO in 1999) and remembers the Fun days well. It seems Emerson Drug, Baltimore’s maker of Bromo-Seltzer, was having some success with Fizzies, a tablet that turned water into a bubbly soft drink—kind of like a fruit-flavored Alka-Seltzer. The spice guys decided to beat the Bromo boys.

“We came up with a granular product, which we thought was better,” the 85-year-old retiree says by phone from his Florida home. “We actually did a lot of TV advertising on it in three test markets [10 more the second year] and we did absolutely great.”

The Mad Men-era ad copy practically wrote itself: laughing, eager-eyed kids yelling, “We’re going to have Fun!” Buzz McCormick even recalls witnessing a boy having a full-on temper tantrum in a Baltimore grocery store after his mother refused to put Fun in their shopping cart.

A major, multi-state rollout was launched and McCormick execs sat back waiting for Fun sales to explode. But instead, the product did. Literally. The foil packaging technology of the day wasn’t up to the crushing production demands and many Fun packets leaked, allowing moisture to seep in. Water is what made Fun bubbly in a glass. And water in the foil packet is what made Fun a ticking time bomb on the warehouse shelf.

“The packets swelled up and burst so loud,” Buzz McCormick explains. “I remember a sales call with a [supermarket] broker in Florida one day, and he happened to put a couple packs on the floor in front of his foot and, by mistake, he stepped on one and it blew up like a balloon.

“Oh Lord, it was a disaster,” especially so in the South’s humid air, he concludes with a chuckle.

Buzz McCormick can laugh about the blunder now that it’s decades behind him. But perhaps his ready mirth is also born of the knowledge that such product flops—or busts, in this case—have been few at McCormick. How else to explain how the company his great Uncle Willoughby founded 125 years ago, peddling root beer extract door-to-door out of a Baltimore cellar, grew into the world’s largest spice maker, with more than $4 billion in annual sales and some 10,000 employees around the world?

In fact, the international business has flourished well beyond the spice rack into a global food giant, with its flavor concoctions now found in most grocery aisles—from baked goods to frozen foods—and in some 125 countries. Huge food chains use them, too. Kentucky Fried Chicken’s 11 herbs and spices? Yes, McCormick supplies some of those. Of course, there’s a certain crab seasoning they produce, too—all part of the company’s compelling history.

Old Bay, the spice most closely associated with McCormick today—at least for Baltimoreans—is celebrating two-dozen years as part of the company’s product line. McCormick, however, didn’t invent the beloved summertime spice, which was the work of one Gustav Brunn, a German Jew who escaped the Nazis and set up the Baltimore Spice Company in 1939. Over time, the unusual spice blend in the yellow tin has even made its way beyond the Mid-Atlantic and across the country, into Canada, and even parts of Europe. “I know I have personally seen it on the menu in the Netherlands,” says Old Bay brand manager Jessica Schatz. “The popular flavor profile of Old Bay is the one people have loved for 75 years. It’s classic, and we would never change that.”

The folks at McCormick also say Oprah lent a hand in broadening the Old Bay fan base when a multi-million selling 1994 cookbook she co-authored called for it in a couple of recipes. (Remember, before she was a one-woman media juggernaut, she was an ambitious young TV personality at WJZ.) Beyond the crab pot, the salty-hot mix is showing up in all kinds of places, possessing a near cult following. The Charmery ice cream parlor in Hampden has a popular Old Bay caramel flavor, while Frederick’s Flying Dog Brewery recently released its Old Bay beer, Dead Rise.

And, although McCormick & Company didn’t give Old Bay its name, Buzz knows how it came about, and it takes him back to his days working at the company’s plant on the Inner Harbor. “Right across the street, the Old Bay Line and Chesapeake Line sent ships to Norfolk every evening at 6 and 6:30,” he says. These passenger steamers sailed into the sunset in the 1960s, but what was initially called Delicious Brand Shrimp and Crab Seasoning, he notes, didn’t take off until Brunn renamed it in honor of these boats.

Still, long before the acquisition of Baltimore’s favorite crab seasoning, as the Fortune 1000 company was cutting a wide swath through the food world, McCormick was leaving a substantial mark on its hometown as well. And it all started with a hard-bitten Virginian armed with borrowed cash and big dreams.

Buzz McCormick was a tyke of four when great uncle Willoughby McCormick died in 1932 at age 68, but he has distinct memories of his ancestor. “He lived two blocks away from us in the Warrenton Apartments on Charles Street,” he says. “I remember being up in his apartment and seeing him and his wife, and she played Chinese checkers with me.

“He had an electric car in those days, and a chauffeur, and he used to go down to the plant in his electric car,” he adds. “How many years has it taken to get back to that?”

Owning the Prius of its day might have been a nod to modernity, but the founder was largely an old-school, autocratic industrialist of the high-collared, 19th-century variety. Or, in his great-nephew’s words: “He was a tight-fisted Scotsman who never threw away a used envelope so long as it still had room for additional writing.” Willoughby McCormick was born in Northern Virginia and developed an interest in the food trade while working at a family general store in Texas. He birthed his business in Baltimore in 1889 because the port city was well positioned as a distribution center. (Coincidentally, the same year that he began peddling root beer in Baltimore, a man named Emile Zatarain began doing the exact same thing down in New Orleans; his effort grew into the bulging Zatarain’s brand of Cajun and Creole food products that McCormick bought 11 years ago for $180 million.)

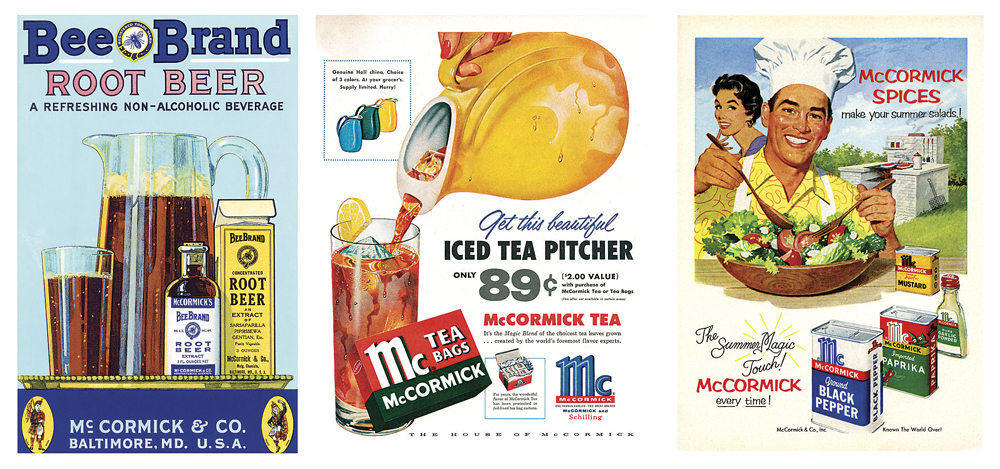

Along with extracts and juices initially sold door-to-door, there were curious non-food items, including Uncle Sam’s Nerve and Bone Liniment “fit for man or beast” and the smelly, fish-based Iron Glue that “sticks everything but the buyer.” Spices didn’t join the fold until Willoughby McCormick bought the F. G. Emmett Spice Company of Philadelphia in 1896—growth by acquisition eventually becoming a McCormick & Company hallmark.

The business had already emerged from its initial year in a glorified cellar to reside in a series of ever-larger downtown locations. But don’t look for any of these old buildings today, because in the Great Baltimore Fire of 1904, you’ll recall, some 80 blocks of the city went up in smoke. “We lost everything but our books, which we got out at about 3 o’clock this morning,” Willoughby wrote in a letter home to his mother. “We had to run for our lives.” The tenacious McCormick had a spanking new five-story factory erected on the ashes of the old before the year was even out. The company soon added tea to its line and helped pioneer the manufacturing of tea bags. (Before machinery was developed to stitch them, the tea bags were handsewn by local church groups as piecework fundraisers.)

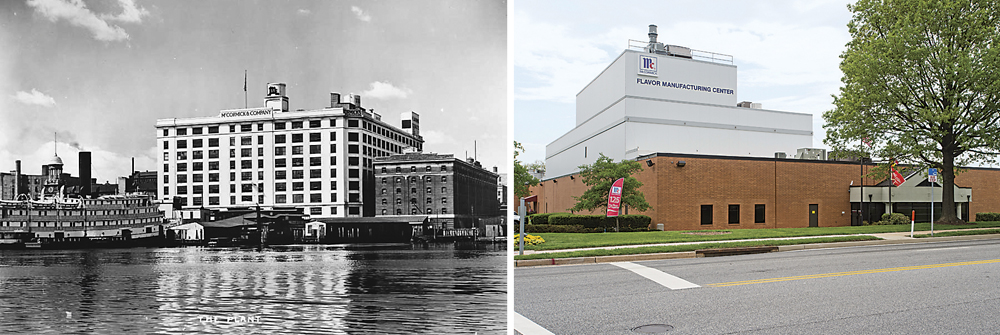

The building Baltimoreans of a certain age will most associate with McCormick is the aromatic, cream-colored, nine-story leviathan that loomed over Light Street and the Inner Harbor for nearly seven decades. Erected in 1921, it competed with the Bromo-Seltzer tower’s spinning blue bottle with a giant rooftop pepper tin and vanilla bottle. Documents of the day gush over the sheer enormity of place—over 12 acres of daylight floor space and some 37,000 windowpanes. Business was booming.

And then it wasn’t. By 1932, the Depression had delivered the company years of red ink. Willoughby McCormick made a desperate trip to New York to secure new loans. Instead, he died of a sudden heart attack. He didn’t have any children, but there were relatives in the business, most prominently his vice president, nephew Charles McCormick Sr.—Buzz’s father, known by all as C.P. And so, at the ripe age of 36, he was the lucky one to assume the helm of the beleaguered business. Previously, the company’s response to the Depression had been hard-handed austerity: Wages were cut multiple times, work hours were increased. The new McCormick in the corner office charted a different course.

“What C.P did was rather incredible,” Buzz McCormick says. “He held a meeting with employees and told them that he was not going to cut wages again but was going to give everybody a 10-percent increase.” Some in the Baltimore business community branded him a communist for his liberal personnel policies, which included profit sharing and free turkeys for workers at Thanksgiving—a practice the company continues to this day via vouchers for the cost of a full holiday bird. His benevolent moves, designed to foster teamwork, were actually the concepts of a shrewd capitalist. This carrot-instead-of-the-stick approach had the business back in the black by 1933. His progressive policies also included something he branded “multiple management,” wherein workers of all ranks were invited to form junior boards with a say in corporate governance. (Well, all male employees—things weren’t that progressive yet.)

McCormick became a coast-to-coast company in 1947 when it acquired San Francisco’s A. Schilling and Company, the largest spice company west of the Mississippi. It, too, dated to the 1880s and also had overcome catastrophe after the 1907 earthquake leveled its facilities. Buzz calls it “the world’s perfect merger,” and the Schilling name didn’t begin to be phased out in the western U.S. until the 1990s.

The second-generation McCormick brought some whimsy to the work as well, most colorfully through the construction of Friendship Court, a detailed recreation of an Elizabethan village—timbered frames, leaded widows, thatch-and-slate roofs—rambling through the Light Street building’s 7th floor. A centerpiece was the Ye Olde McCormick Tea House where, as late as the 1980s, women in hooped skirts and petticoats distributed free tea and cookies to tourists beneath a beamed ceiling.

Although McCormick is a public company, not a family one, there have always been namesake employees in the business. John McCormick, Buzz’s half brother, is presently vice president of government affairs and community relations, though slated to retire in December after 45 years. He, too, started as a teen on Light Street.

“My worst memory was getting inside of a steel container we used to make mayonnaise to clean it out,” he recalls. In the summer of 1976, an armada of tall ships arrived at a pre-Harborplace Inner Harbor for a four-day celebration, and he remembers this, too. “Mayor Schaefer called [us] and asked, ‘What can you do to make the harbor smell good?’” John McCormick says. “Of course, we always tried to do everything to keep odors to a minimum. But, we scheduled all our cinnamon to be processed on those four days, and we allowed more of the cinnamon dust to get out than would normally be the case. I won’t go into how, but the harbor smelled great.”

The harbor also smelled great on a more somber occasion—during the weeks it took to knock down McCormick’s cement behemoth factory in 1988. Each blast of demolition equipment ushered up decades’ worth of spilt spice dust—a scented swan song.

McCormick had begun the piecemeal relocation of operations to the Hunt Valley area in the early 1960s. Eventually, only a bit of spice milling was left on Light Street, where the railroad tracks and cobblestones had been replaced with carloads of daytrippers flocking to Harborplace. The empty structure was sold to the Rouse Company, which demolished it over the ardent cries of preservationists, who lamented losing such a landmark of industrial heritage. Plans have come and gone for the parcel, which has remained a parking lot to this day, and proposals are again afoot to erect a skyscraper there.

Two years ago, McCormick opened its World of Flavors “retailtainment” center in Harborplace, returning, if on a much smaller scale, some scent of spice to the Inner Harbor. But now that McCormick HQ is tucked away in a leafy suburban office park, rather than perfuming downtown from a mammoth building topped with an oversized pepper tin, it’s safe to say the company has a much lower local profile. (There are concerns, as McCormick looks to consolidate more of its office workers under one roof, that some local jobs could potentially move to nearby Pennsylvania, but the search for new office space has just begun, according to a company official.) Parts of Friendship Court were moved and rebuilt in the new building, though it’s no longer open for public tours. Also not open to casual visitation is what they call the “global market” tucked in the headquarter’s fourth floor. On a recent workday, corporate communications director Jim Lynn led a reporter on a small tour around the sprawling mock store where shelves are lined with McCormick goods from around the world.

The familiar McCormick spice display from your local Giant or Safeway is herewith its red-capped wares, as are some of the ethnic lines geared to the domestic market, such as Thai Kitchen and Simply Asia. But most of the shelf space is given over to a polyglot of foreign brands the company has acquired through the years: Club House (Canada, 1959), Schwartz (UK, 1984), Aeroplane (Australia, 1994), El Guapo (Latin America, 1999), Margão (Portugal, 2000), Vahiné and Ducros (France, 2000), Silvo (Holland, 2004) Kamis (Poland, 2011), and Kohinoor (India, 2011). Business with China began in the late 1980s, and McCormick China was founded in 1998 and two additional Chinese food brands were bought just last year.

“These retail consumer products represent about 60 percent of McCormick’s business today,” Lynn says. “About 40 percent of the business is selling to food manufacturers and restaurants. And it’s more than them just saying, ‘Hey, back up a truck-load of cinnamon,’ our R&D department actual helps them develop the products.”

As far back as World War II, when access to spices such as pepper and cinnamon were severed, McCormick has explored the natural and chemical components of flavor in the lab. Now, an army of white-coated scientists go at it like gangbusters here. It’s a safe bet that the flavor profile of the latest bag of chipotle cilantro chips, or what have you, was born in the Baltimore suburbs off of I-83.

In 1998, The New York Times ran an article on McCormick, “Trouble in Spice World,” and quoted a Goldman Sachs analyst’s warning that the business “does not have a lot growth in it.” People were cooking from scratch less and eating out more, the analyst figured. Oops. McCormick’s net sales and profits have nearly doubled in the last decade alone. Globalization is part of that. And so are the Food Network celebrity chefs and Martha Stewarts of the world engendering renewed interest in cookery. And if people do opt to dine out? Chances are they will eat McCormick there as well, at the drive thru or the white tablecloth restaurant. There is even a special “McCormick for Chefs” line.

“Make the best—someone will buy it” is the old McCormick motto carved into the Ye Olde Tea House mantelpiece—long said to be Willoughby’s words. But in his 1993 corporate memoir, Pepper People, Buzz McCormick came clean, reporting that his father created the quote and attributed it to his uncle (who was probably too busy squirreling away used envelopes and conjuring up new goods to go in for much sloganeering).

A less formal saying now floating around the corporate offices goes like this: “On any given day, the odds are you consume a McCormick product.”

Even flinty old Uncle W. would probably crack a smile at the thought of that.