Food & Drink

Let's Get Pie Style

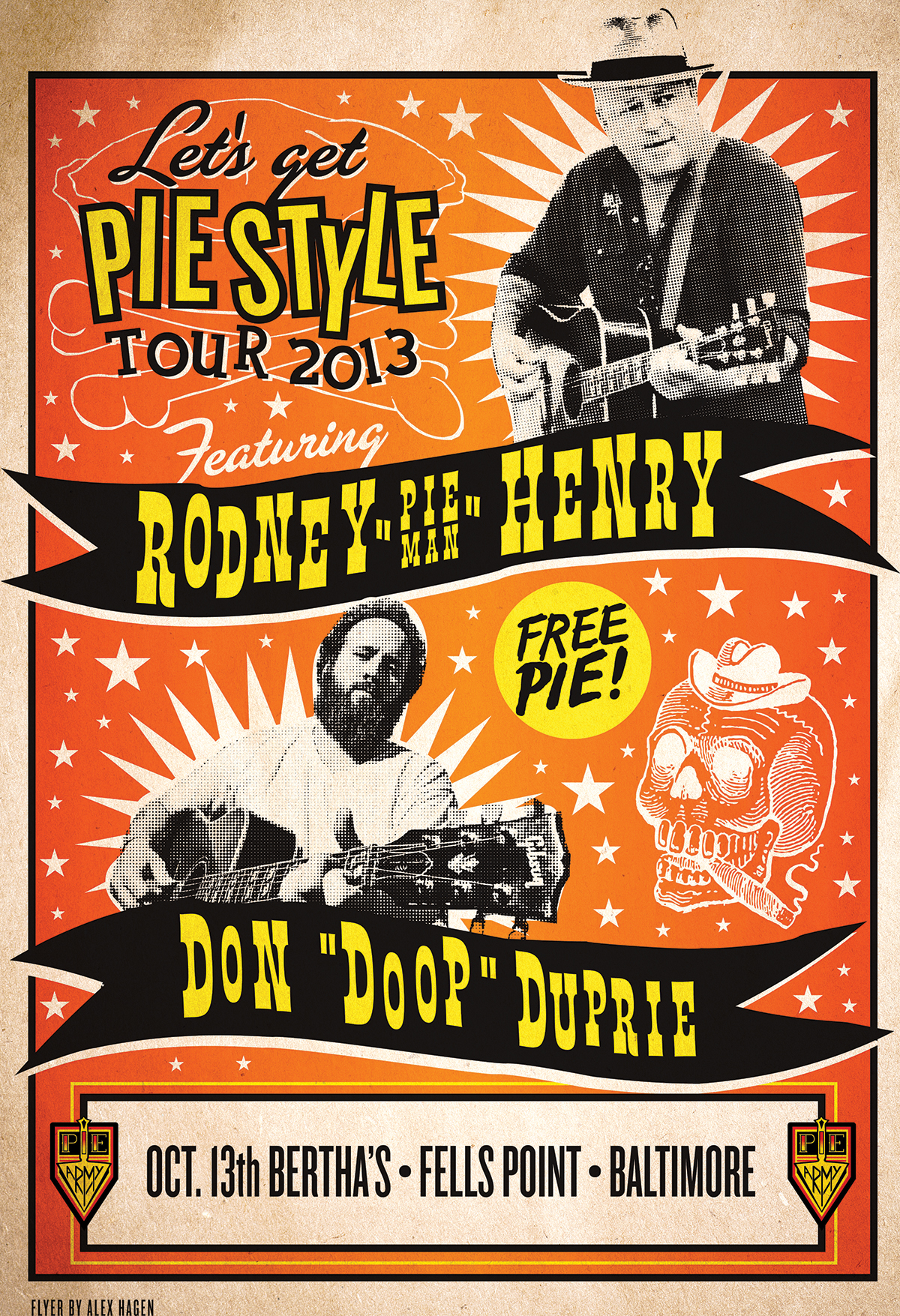

Rodney Henry rocks out on baking and music.

Baltimore’s Pie Guy/Music Man sits at an outdoor table in Fells Point on a balmy fall night, waiting for a gig to start at Bertha’s.

As he sips his favorite indulgence—Jack Daniels and water—he shoots the breeze about everything from his recent appearance on Food Network Star to an upcoming month-long band tour that will take him from his hometown to Ohio and Texas and places in between. Wearing his trademark porkpie hat, he doesn’t go unnoticed as passersby nudge each other and whisper, “That’s Rodney Henry.”

Henry, 48, greets them all, shaking hands and giving brotherly bear hugs. He’s thrilled that one guy is wearing a Dangerously Delicious Pies T-shirt, a testament to the baked goods he started rolling out for sale 10 years ago. Recognition in his hometown is about as sweet as the popular Baltimore Bomb pies, made with Berger Cookies, that are sold at his Canton shop.

But he doesn’t just get attention here. After his summer run on the TV show—where he proclaimed that “pie style” is a way of life—he’s approached by fans at airports and other public places around the country.

“More people recognize me,” he acknowledges with his signature sly grin and mischievous blue eyes. “We talk smack. I love it. It’s fun.”

Lazlo Lee, the head baker at the Dangerously Delicious Pies in Canton, likens Henry’s burgeoning popularity to that of blues musician John Lee Hooker, who didn’t become well-known until he was in his 50s. “He’s slowly being recognized,” he says. “I call him the Colonel Sanders of pie. He’s become [an icon] except he wears a leather jacket and that freakin’ fedora.”

Lazlo Lee, the head baker at the Dangerously Delicious Pies in Canton, likens Henry’s burgeoning popularity to that of blues musician John Lee Hooker, who didn’t become well-known until he was in his 50s. “He’s slowly being recognized,” he says. “I call him the Colonel Sanders of pie. He’s become [an icon] except he wears a leather jacket and that freakin’ fedora.”

Henry is a presence with his noticeable tattoos—the pie wings are a favorite—and the distinctive brimmed hats covering his slick, shaved head.

“He’s a charmer. He’s larger than life,” says local rockabilly musician Sean K. Preston, who was on hand for Henry’s Fells Point show. “He’s a helluva guy.”

Henry has come a long way from his days on the campus of Towson University, where he majored in “fun” when not attending his mass-communications classes. He ended his college career short of graduating. “I went to school to chase girls,” he says sheepishly. “I was a party guy, man.”

Not that his footloose lifestyle has changed. After his 11 p.m. show at Bertha’s, he takes an entourage of friends—including his opening acts Alison Lewis and Don “Doop” Duprie, both from Detroit—back to the Guilford five-bedroom home he calls the “pie palace” and the “house that pie built,” where they jam until 7 in the morning.

One of Henry’s most well-known songs is “Paperboy,” an homage to his days as a Washington Post delivery kid in Silver Spring, where he grew up in a middle-class suburban household with busy parents—his dad was a computer-company salesman; his mom, a political activist—two sisters, and a brother. He’s the only musician in the family. “My parents are super supportive,” he says. “My dad is so proud, though he asks me, ‘Why can’t you be like Sinatra?’”

He chuckles about his father’s comment. Being a ’40s Rat Pack crooner was never an aspiration for Henry, who often sports colorful Western-style shirts, cowboy boots, and jeans while belting out the blues and strumming his Gibson guitar on stage.

He’s been a professional musician since he was 24 but started with the trumpet in elementary school. Not that he was particularly gifted in the beginning.

“When I was 13, I did Beach Boy covers in junior high,” he says. “I was horrible.” He really learned to play the guitar when he was a Marine Corps grunt after high school, he says, jamming every night with the other recruits while stationed at a Naval weapons base in Northern California.

His current band is the Glenmont Popes, named after his childhood neighborhood in Montgomery County and one of his favorite movies, The Pope of Greenwich Village (1984) with Mickey Rourke and Eric Roberts.

“Popes are the people you go to,” explains Henry, the band’s front man. “It’s a slick thing.”

It’s hard to say what came first: the musician or the baker. He learned to bake cakes and bread as a teen from his grandmother and great-aunt, while visiting the family farm in Minnesota. But Henry also remembers being enamored early on with a 25-cent slice of apple pie at a local diner.

“I’ve always been a pie guy since I was a little kid,” he sums up. He also found he could impress the girls with his homemade pies, recalling a Christmas past when he made a flaky offering (lard was his secret ingredient then) for a former young love, culling a recipe from a book called Pies and Tarts.

More importantly, Henry began to realize the bonding aspect of the baked dish. “Pie lets people talk to each other,” he says. “It encourages conversation.”

But music also beckoned, leading him to tour the U.S. with an eight-to-10-member “low-echelon” band. “I wanted to be a musician,” he says. “If you’re a musician, you’re a musician.” Life on the road didn’t always pay the bills, though, especially with a wife and young children. Henry found that selling pies gave him the extra income he needed. “I make pies, so I can pay for my rock-and-roll habit,” he says.

Henry is now twice divorced, and his two children—Waylon, 10, and Lily-Anne, 8—live in Melbourne Beach, FL, where he is a frequent visitor. “My body and mind need the down time with the kids,” he wrote recently on Facebook. On holidays, the children often travel with him. They have learned to accept their peripatetic dad: “The road is my home,” he says. “I have a traveling bone.”

Henry came to Charm City to live when he was 25. “I’ve always had a fascination with Baltimore,” he says. “I represent Baltimore.”

The entrepreneur got his start in the economic world of crusts and fillings—his pumpkin pie was recently picked as one of the top Thanksgiving pies by Food & Wine magazine’s website—by turning out pies that were sold at the Daily Grind in Fells Point in the late ’90s. At the time, he was also moonlighting as a waiter and bartender at Peter’s Inn, not coincidentally, one of his favorite restaurants (along with Sticky Rice).

“He’s a jack-of-all-trades,” says Bud Tiffany, who owns Peter’s with his chef/wife Karin. They both have one thing to say about Henry, who, even now, occasionally helps out at the former biker bar: “Best. Employee. Ever.”

By 2003, Henry took over an old Herman’s Bakery at South Montford Avenue and Fleet Street with financial support from his parents and brother-in-law. Today, he has a mini-chain of pie shops with the Canton location, three in D.C., and another in Detroit—plus food trucks. And the empire is growing. He’s negotiating to open a Dangerously Delicious Pies in Austin, TX, and is considering a spot in Napa Valley, CA, where he envisions a “farm-to-table” theme in keeping with the area’s all-year growing season. “I’m like a pie bastard,” he admits.

The name for his business just came to him one day while he was driving his car, he says. He liked the sound of Dangerously Delicious Pies and envisioned the cross-bones logo that distinguishes his brand.

But these days, Henry isn’t usually doing the day-to-day dough making. He has other partners involved.

“Rodney doesn’t like the word ‘franchise,’” says Mary Martian Wortman, who owns the Canton Dangerously Delicious shop with her husband, John. “Rodney doesn’t want the shops to be cookie cutters.”

Mary, a longtime believer in the pies and Henry, left a teaching job at a private elementary school in Dundalk to follow the master, who trained the married couple in all aspects of the business. “I believe in his product—his pies are like no one else’s—and his marketing ability,” she says. “And it freed him up to do what he does best.”

Henry is still very hands-on at the shops when he has time, even getting behind the counter. “I keep it so it’s personal. I have a vested interest,” he says. “I get a cut of the action.” He doesn’t talk exact amounts of money, but he says, “It will help with the kids down the line.”

Henry is still very hands-on at the shops when he has time, even getting behind the counter. “I keep it so it’s personal. I have a vested interest,” he says. “I get a cut of the action.” He doesn’t talk exact amounts of money, but he says, “It will help with the kids down the line.”

The diversity of his shops—which all use the same recipes for the pies, quiches, and side dishes and have similar color schemes of red, black, and gun-metal blue—is particularly evident in Detroit. The pie enterprise is in a tavern—the Third Street Bar near Wayne State University. Musician “Doop” Duprie—who played at Bertha’s—runs the place.

Henry met Duprie, a songwriter and singer/guitarist with the Michigan alternative-country group Doop and the Inside Outlaws, at South by Southwest, a film-and-music festival in Austin, while he was playing music and slinging pies. Duprie heard Henry sing there. “I was blown away,” he says. The men became friends, and Henry went to Detroit, where the two recorded music and hung out.

While Henry was there, the bleak employment outlook in the Motor City wasn’t lost on him. “I love Detroit,” he says. “There are no jobs, so I said, ‘Let’s open a pie shop.’”

He put Duprie, a laid-off firefighter, in charge of the new business, bringing him to Baltimore for a month to train and learn how to bake pies. Duprie, who cooked for the firefighters at his former station, was a quick study. And he is grateful for the job opportunity, especially since the two-year-old operation is already showing a profit. “He’s a good man with a big heart,” he says of Henry. “He does a lot of stuff for other people. He’s this guy who comes in and creates jobs.”

Henry accepts his role matter-of-factly: “I’m spreading the word of pies.”

Duprie isn’t the only musician to benefit from Henry’s largesse. Lee, Canton’s head baker, also received a helping hand. The Baltimore singer/guitarist, who frequented a former Dangerously Delicious shop in Federal Hill and met Henry there, was on the verge of being laid off from his job working on electric cars in an industrial park near Camden Yards. Henry heard about Lee’s plight, called him, and invited him to come to work. Lee, who learned to bake as a child from his mother, fit right in.

A number of Henry’s employees are musicians. The open kitchen in Canton allows easy viewing of the baking action, whomever is patting the dough into a pan or cutting up fruit and vegetables. The savory pies—especially the plump steak, Gruyère, and mushroom and the pulled-pork barbecue—are as popular as the sweet pies of apple, blueberry, lemon chess, and—one of Henry’s favorites—the “white-trash crème brûlée.”

The pies aren’t cheap: A whole pie is $28 for a sweet one ($6 a slice) and $35 for savory ($7 a slice). But Wortman, who took over the Canton location on O’Donnell Street a year ago, says that she and her husband are “taking it slow and sinking the revenue back into the shop.”

They also have an entertainment license now and book music acts on occasion, which certainly fits into Henry’s concept.

“He started his pie shop to extend his music career,” says Lee, whose band Lazlo Lee and the Motherless Children performs locally and around the

country. “He’s all about ‘pie style.’”

Ah, “pie style,” the phrase Henry made famous on last summer’s Food Network Star, where he was one of 12 contestants vying for a chance to have his own TV show. What exactly does it mean?

Essentially, it’s a way of life, a work ethic, a loyalty to those of similar interests. As Henry explains it vaguely, “It’s a laid-back attitude.”

While Henry was a fan favorite on the show, he came in second to Southern cooking-school instructor Damaris Phillips. His followers rallied around him, as Elizabeth Smith posted on Facebook: “Rodney should have won . . . hands down . . . but he will always be the pie guy. Nobody can beat that!”

The worst part about the show, Henry says, was not being able to talk about the results. “I’m a loudmouth,” he shares. “It had to be a secret.”

He had a good time, though, enjoying the repartee with celebrity mentors Giada De Laurentiis, Bobby Flay, and especially Alton Brown. “Me and Alton are totally cool. In the morning, we’d hang out and talk about rock-and-roll,” Henry says. “He was the most personable of all the judges.”

He would like to catch up with Brown when the TV celebrity brings his Edible Inevitable Tour—featuring stand-up comedy, live music, food talk, and more—to Baltimore on February 22 at the Lyric. “If I’m here, I’ll see him somewhere on his tour,” Henry says. “I’m going to stalk him.”

The recent TV stint wasn’t Henry’s first shot at national fame. He has also appeared on the Food Network shows Chopped and Throwdown with Bobby Flay.

But there’s still hope for Henry on the small screen. While he can’t talk about the specifics, discussions are in the works for his own program,

which he describes as a lifestyle show involving music, food, and bars.

“Sort of like Anthony Bourdain, but not so highbrow,” he suggests with a laugh.

His friends envision a starry-eyed future for him. “I can see him teaching bands how to bake pie or going mobile and teaching a band like U2 to make pies,” Lee says.

“I think with his positive attitude—and he’s sure driven—he’s bound to have something happening,” Bud Tiffany agrees.

For the next several months, Henry will be spending time in Los Angeles, working on the mystery TV possibility, and traipsing around the country in his usual fashion. “My life is killer,” he says. “I’ve got nothing to complain about. I’ve been ‘pie style’ since day one.”