Arts & Culture

In Boh We Trust

National Bohemian hasn’t been made in Baltimore for decades. Not that anyone seems to care.

By Lydia Woolever

HERE’S WHAT I’M GOING TO TELL YOU, and then there’s what really happened.”

This is how our conversation begins with David Knipp as we climb an industrial staircase, heading toward the top of Natty Boh Tower on the edge of East Baltimore. In mid-July, his summer tan is solid, and in khakis and loafers, he exudes the sort of casual, convivial attitude of some kid you know from high school, the kind who helped cement the city’s nickname as Smalltimore.

And today, the 61-year-old Gilman grad is leading us on a tour of this building—a nine-story, red-brick behemoth standing tall on the corner of Conkling between Dillon and O’Donnell streets, in the neighborhood now known as Brewers Hill, outside of Canton—whose history in recent years he’s learned so much about.

“Though Cal knows more than I do,” says Knipp, nodding toward Calvin Gundlach, who chuckles through a thick bleach-white mustache.

And he’s right. Down the hallways, up the narrow elevator, past the relatively new office spaces, Gundlach can readily orient himself around every corner. After all, the 72-year-old spent a lot of his life in this building, and though soft-spoken at first, he likes to reminisce.

“I’m trying to hold back,” says the Hudson Street resident, a Bawlmer accent drawing out his Os as each forgotten memory suddenly rises to the surface.

Like how it all began for him on June 9, 1970. He had just sat down to celebrate his 18th birthday when the phone rang. The voice on the other end of the line informed him that he’d gotten a job at the National Brewing Company. It was 4:30 p.m., but could he be on-site at five? “I ran up the street with my birthday cake,” says Gundlach, causing Knipp to crack up. He hadn’t heard that one before.

Through the clatter of a metal door, we finally reach our destination—the roof. It’s arguably one of the best views in all of Baltimore. To the west, you see out over the early rowhomes of Canton, then Fells Point, then Little Italy, all the way to downtown and the Inner Harbor. To the south, the Port of Baltimore and the Patapsco River. To the north, the Johns Hopkins Bayview hospital, and to the east, the highways, and maybe, just maybe, if you squint hard enough, where the land rolls off of Essex into the Chesapeake Bay.

“Down there, that was our bottling and canning department, and over there was a warehouse, and over there, those new houses? Those were the tin shack, where they’d unload for the packaging center,” says Gundlach, his arm eagerly outstretched, pointing over the concrete ledge.

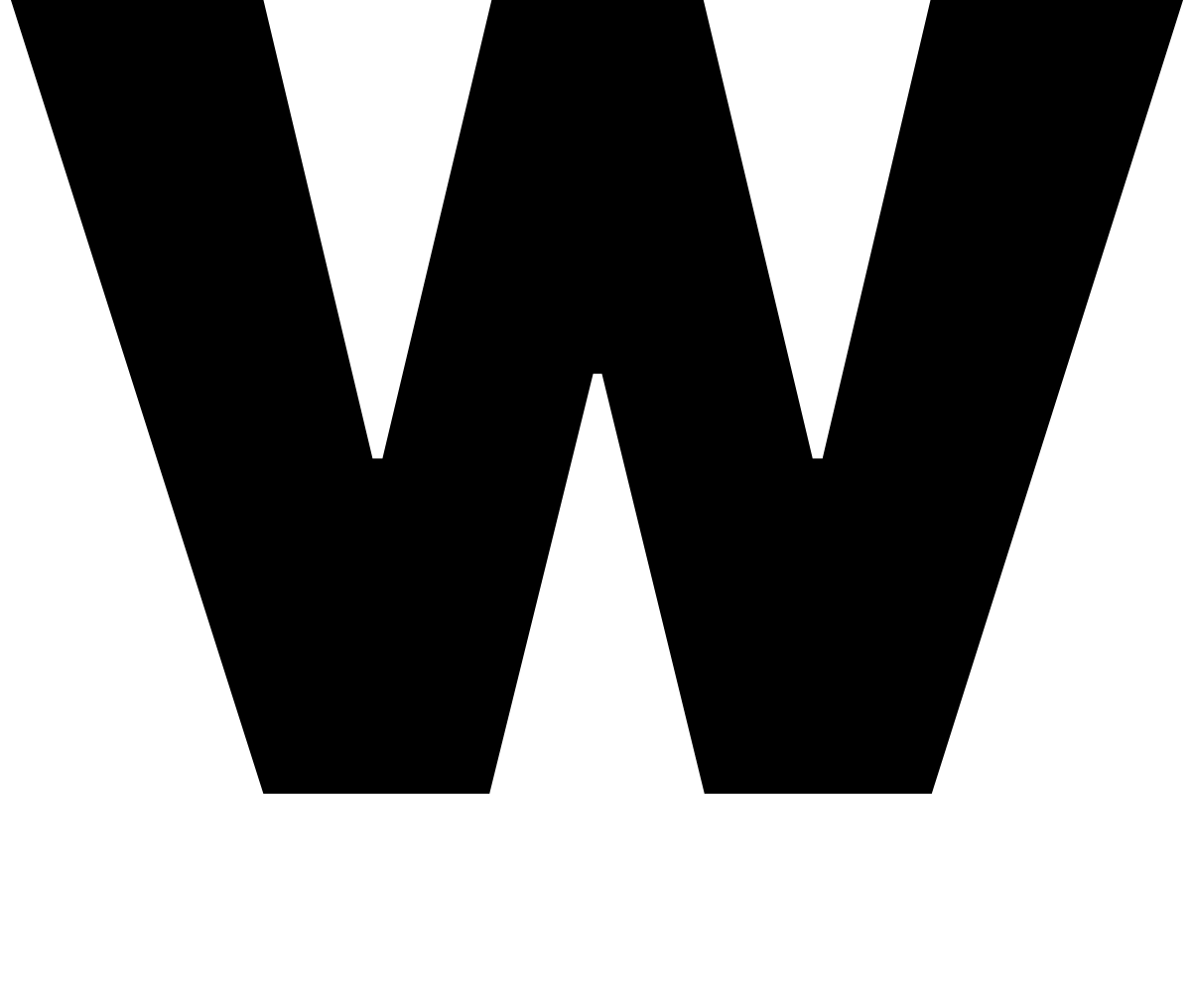

At one point in time, the National Brewing Company occupied five city blocks here, running all the way over to the rail lines on Haven Street. Dating back to at least 1885, it was its own bustling factory town, employing nearly 1,000 people, from bosses to brewmasters, warehouse workers to delivery drivers, salespeople to secretaries—altogether hustling to create the city’s best-selling National Bohemian beer.

“Everybody got along, it was just a great place to work, . . . and all the beer you wanted to drink,” says Gundlach, recalling that on Fridays, he and the rest of his union colleagues could buy a case of the stuff for as little as two bucks (with the higher-end National Premium only available once a month). “But that was back in them days. It’s not like that no more.”

What he means is, Natty Boh Tower, and much of the old National campus, as well as the adjacent buildings of their old competitor, Gunther Brewing, are now a massive mixed-use redevelopment, situated across 30-plus acres and totaling more than two-million square feet of commercial, residential, and storage space, run by local developer Obrecht Commercial Real Estate, where Knipp is VP.

Beer hasn’t been brewed here since 1978, when National, under new out-of-state ownership, moved its operations to Halethorpe. Within another two decades, those doors closed, too, and just like that, the last old beer of Baltimore—the namesake of this tower, the icon of its underdog city, the entire reason that Maryland is called the “The Land of Pleasant Living” (more on that later)—left this town for good.

And at the same time, it never quite did.

A vintage-style mural on the old National building in Brewers Hill.

ational Bohemian. National Boh. Natty Boh. Boh. Whatever you call it, the beer has become the stuff of legends here in its hometown of Baltimore. So much so that a solid portion of the population doesn’t even know that it’s no longer brewed here—let alone that it hasn’t been since 1996.

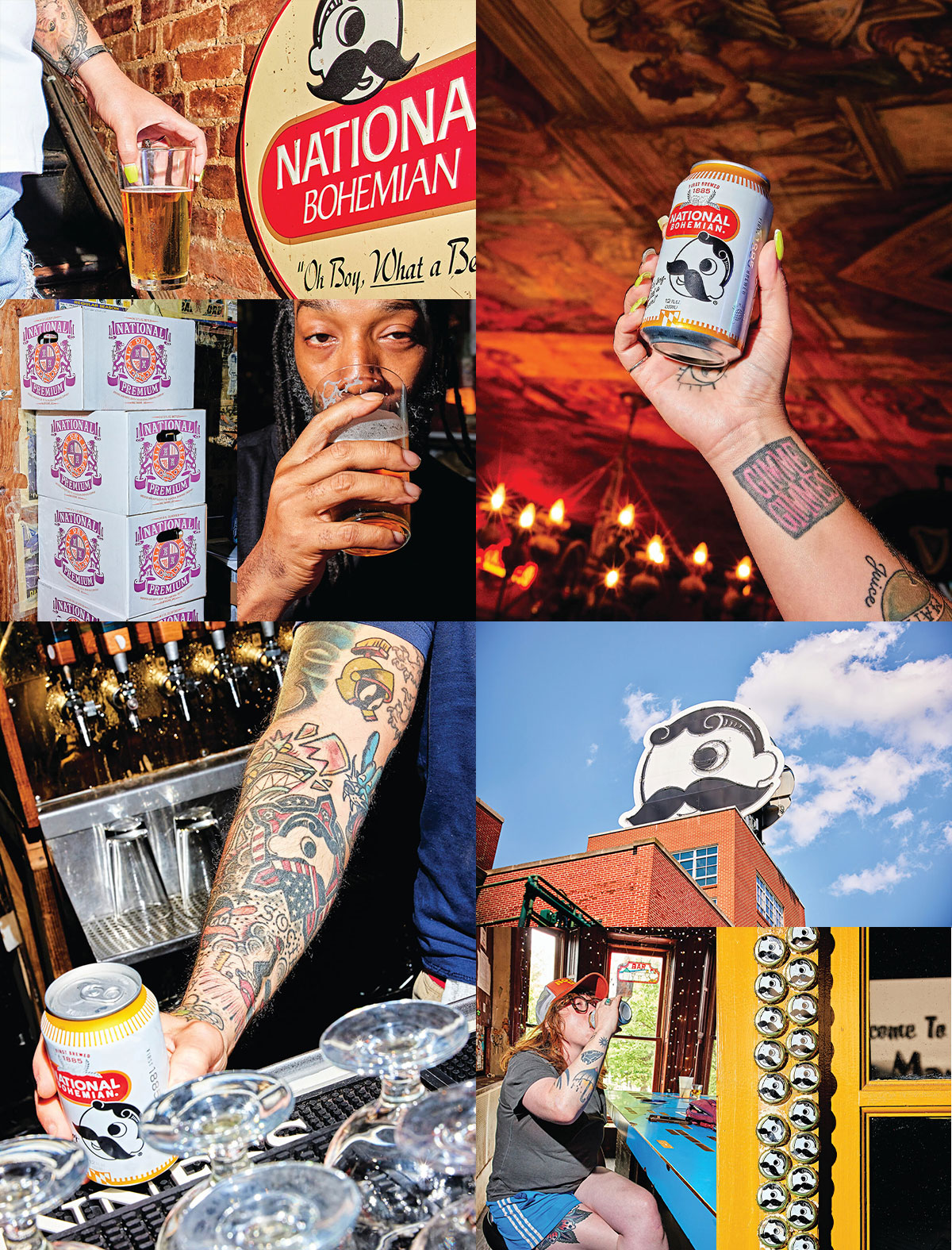

And yet, wherever you go in this city, if not the entire state of Maryland, there it is. At the hundreds and hundreds of bars that carry it—dive bars, craft beer bars, fancy cocktail bars, restaurant bars, you name it—where you’ll find it as 12-ounce cans or tallboys, bottles or drafts, for lunch beers or late-night chasers. Not to mention flowing at crab feasts, and baseball games, and football tailgates, and college and birthday and retirement parties. Or being cracked on our stoops, atop our roof decks, or while cutting the lawn. Of course, walk into any liquor store, and you’ll be hard-pressed not to stumble upon at least a few 30-packs, stacked on the floor or in the fridge like Tetris.

“We do quite a good business,” says Tim Haus, manager at Wells Discount Liquors near Towson, where they sell over 100 cases of “thirties” alone each month. “I mean, everybody knows that one-eyed guy. And then out-of-towners always get it, because it’s Maryland. I tell them, ‘If it’s ice-cold, it’s delicious.’”

Indeed, by every measure, we’re still drinking Boh—some 370,000 cases of it a year, according to Pabst Brewing, its present-day, Texas-based parent company, which somehow saved the beloved beer from total extinction on the eve of Y2K. It stopped being brewed here even before that—most recently in Ohio and Georgia, and now, as of two years ago, just over the line in Pennsylvania. But for a state with a fanatical sense of local pride (see: our flag, Old Bay, Royal Farms, and so on), that has never really seemed to bother us. In fact, nearly 90 percent of all the National Bohemian made these days is sold right here in Maryland, the majority of it in Baltimore.

And not only are we drinking it—we’re shotgunning it, beer-bonging it, keg-standing it, metaphorically speaking. Meaning, we’ve turned it into a way of life. Even for those of us who don’t drink it.

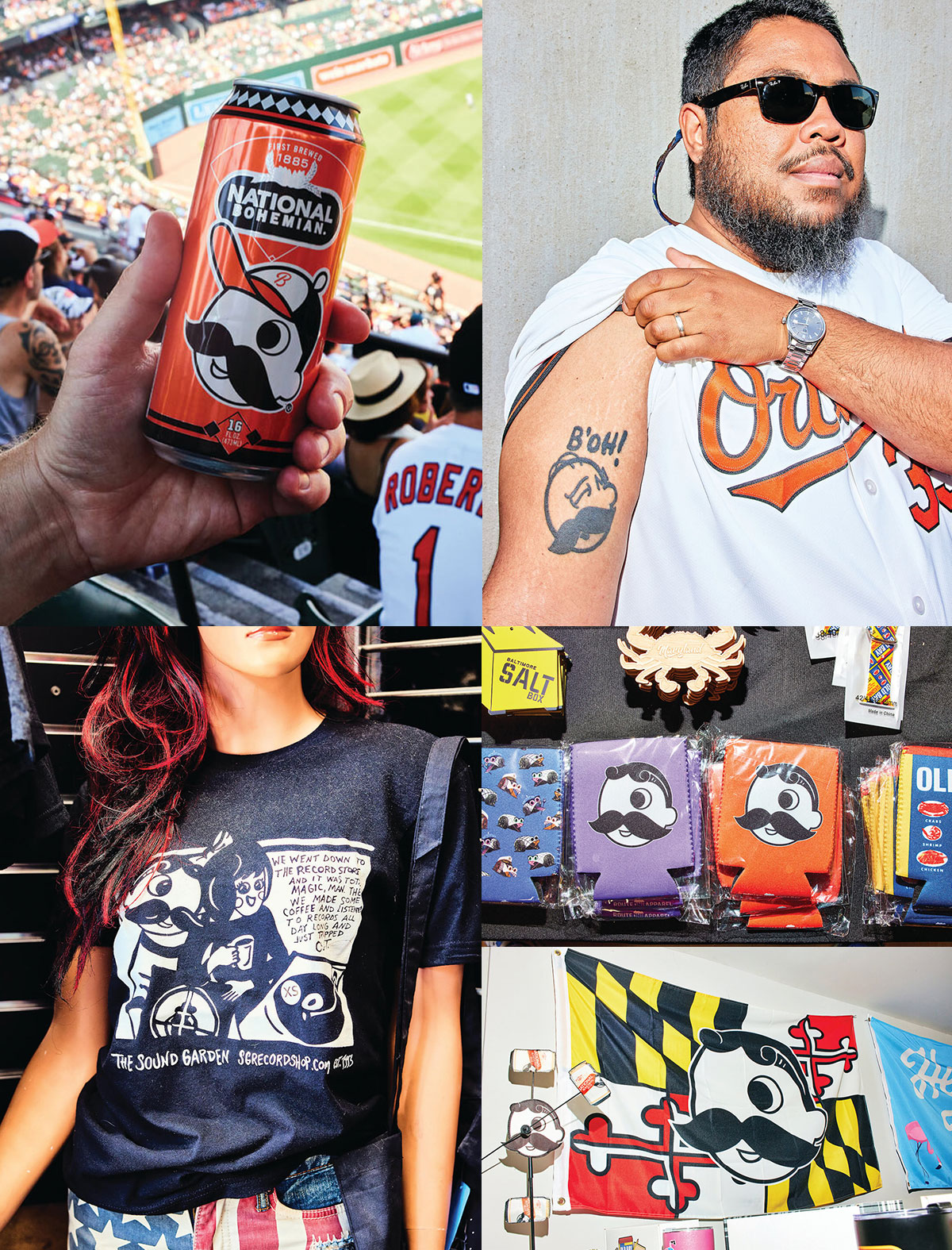

Call it a fever, a mania, a phenomenon, a cult—it’s all accurate, because Boh is everywhere here. Not just in our pint glasses and koozies, but also on our bumper stickers, and our baseball caps, and our baby’s onesies. On the sides of our buildings. On our street-corner saltboxes. We name our partially blind pets in its honor. And, like some sort of tribal ritual, we literally tattoo its mascot onto our own skin.

“Intense” is one way to describe the fandom, per Evan Athanas, who sells Natty Boh through his distribution company, Chesapeake Beverage. “Rabid” is another.

“There’s just this extra level of loyalty,” says Athanas, a St. Louis native and former head of sales at Anheuser-Busch. “Baltimore has this chip on its shoulder. Like St. Louis, it’s a second-tier city, with a bad reputation, but it’s an amazing place to grow up and raise a family, and the people are just so proud to be from here. Like, ‘I know something you don’t know, that this is a great fucking place’—mind my language. ‘And I’ve got my belt, and I’ve got my T-shirt, and I’ve got my beer.’ Like they want you to ask them about it, so they can tell you. . . . ‘Well, I’m from Baltimore, by God!’”

Bill Stevenson inks a Boh tattoo.

But the question remains: why are we so obsessed with this, by all accounts, average beer? One described by Baltimoreans as “really okay,” “inoffensive,” and “a notch above water”—the kinds of fighting words that only we could say. Well, that’s as hard for people to put their finger on as it is for them to remember the first time they had one.

“I just remember being a kid, having a sip of my grandfather’s beer, or surreptitiously sneaking one from my parents here or there,” says Bill Stevenson, 60, a Waverly native, and owner of the Waverly Tattoo Company in Remington, who has inked countless Boh tattoos onto both locals and tourists. “I mean, there’s something to be said for its staying power. . . . People still feel a connection. Maybe their family drank it, or maybe it was the first beer they ever had. And when I was growing up, not only was it made in Baltimore, but there was a pretty good chance you knew someone who worked there.”

bout a mile as an oriole bird flies southwest of Natty Boh Tower, an immigration pier once stood in the shadow of Fort McHenry in Locust Point. For nearly 200 years, Baltimore was one of the largest ports of entry in the nascent United States of America, with a historic boost beginning in the 1860s, thanks to a partnership between the B&O Railroad and the Norddeutscher Lloyd steamship line, providing safe passage for immigrants in search of a fresh start. Through 1920, more than one million people would pass through this terminal—a portal into the city’s, and Natty Boh’s, future.

“It was a massive influx that had a huge impact,” says Maureen O’Prey, local beer historian and author of Brewing in Baltimore. “Together, these people are building communities. And they are building Baltimore.”

Like generations who came before them—the grandparents of Babe Ruth or H.L. Mencken—many of the first to arrive were German, making up about a quarter of the city’s booming population by the 1870s, at the height of the Industrial Revolution. They started schools, built churches, founded newspapers, and, of course, opened some of the city’s very first breweries.

There were more than 40 brewhouses in Baltimore by the turn of the 20th century, located across the city, with several relics still standing today. Like on the corner of Park Avenue and Fayette Street downtown, where a bone-white Renaissance Revival building—the circa-1895 Brewers Exchange, with its intricately embellished façade—is a reminder of the local brewing industry’s early heyday. On a smaller scale, many of the first corner bars opened thanks to financial backing from the makers of the beer brand they served.

It was around this time that the original iteration of the National Brewing Company was born. It’s said that, in 1850, a Fells Point brewer by the name of Johann Baier leased the northeast corner of Conkling and O’Donnell streets, expanding up to Dillon within the next decade, on the city’s eastern hinterlands then known as Lager Beer Hill. Hand-dug cellars were the foundation of what would eventually become the largest brewery in Baltimore, a few of their brick remnants still at the current building’s base. After Baier’s death, his widow and her second husband took over operations, adding a beer garden, tavern, and stables, with barrels delivered locally by horse-drawn cart.

But by 1885, they went bankrupt, ultimately selling the business to their malt suppliers, who renamed it the National Brewing Company. Within a few years, they expanded east to Eaton Street, then merged with more than two dozen other breweries to create the Maryland Brewing Company, hoping that shared resources would help them create more affordable beer at a higher profit—an early economy of scale. Which is exactly what they did. Until Prohibition kicked the keg in 1919.

During the decade-plus national alcohol ban, many breweries closed, including National. The equipment was sold and the buildings were gutted, leaving the place all but vacant by 1933, when Prohibition was repealed and the local Hoffberger family swooped in to buy it. In the flick of a bottle cap (invented in Baltimore by Crown Cork and Seal Company founder William Painter in 1892), the brewery was given a facelift and began brewing beer once again.

“The whole town is talking, drinking, boosting National Beer,” declared an advertisement in The Baltimore Sun in January 1934, right after the first new bottles hit market. And for good reason—they had hired brewmaster Carl Kreitler, known as “the Escoffier of the brewing industry.”

Evolving from steam to electric power, the new state-of-the-art facility became more mechanized and standardized, increasing both quantity and quality. It was an era of innovation—during which National even apparently invented the six-pack—and soon enough, the advent of canned beer allowed their product to be transported farther, and last longer, too.

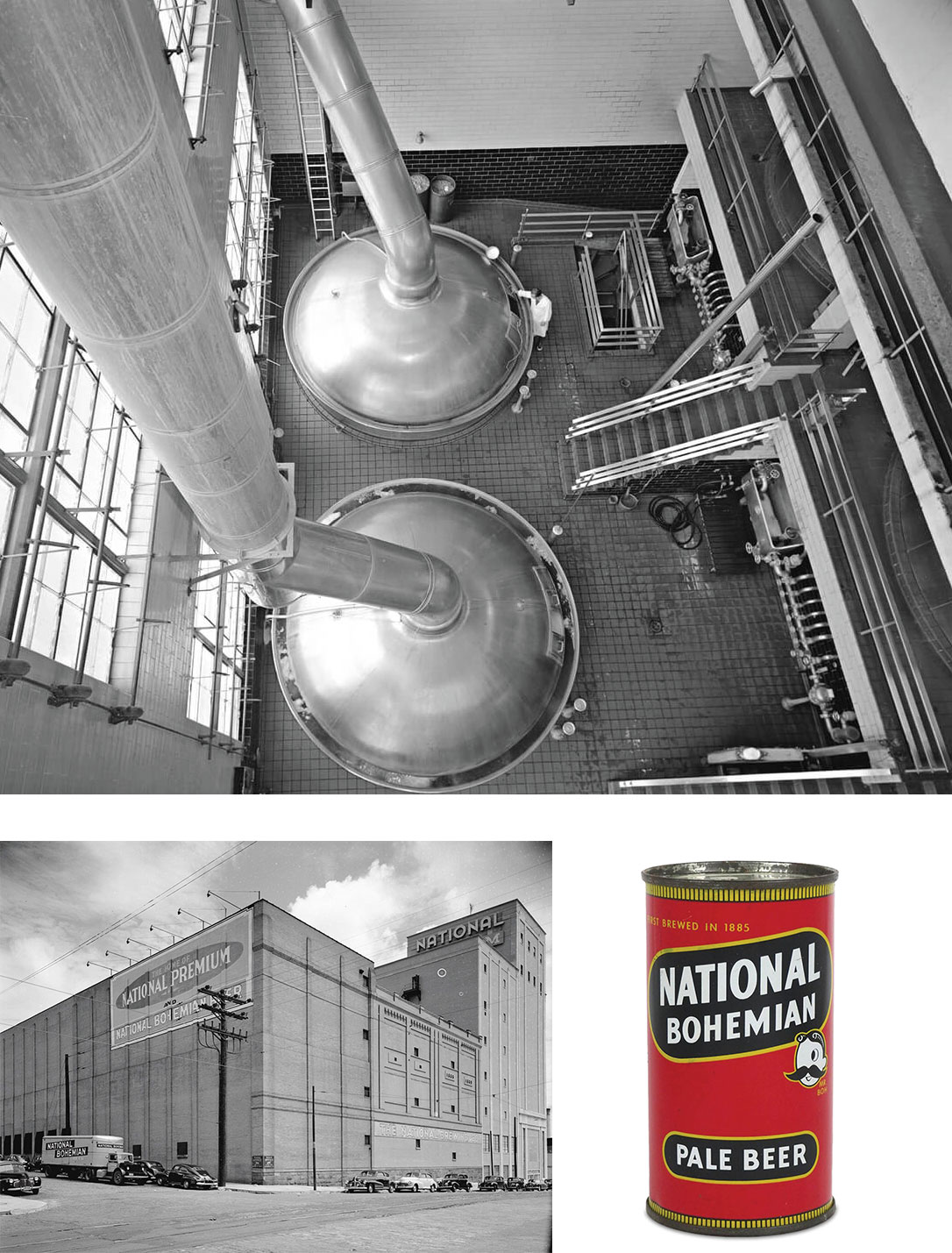

A worker

stands among the

wooden casks

at the National

Brewing Company,

1946.—A. Aubrey Bodine: B815G/Courtesy of the Maryland Center for History and Culture

“You had shipyards, you had steel, you had Domino Sugar, but in Canton and Highlandtown, the breweries were the main source of work,” says O’Prey. “Everybody had a family member who worked there. It was an integral part of the community.”

With its new digs, National was turning out hundreds of thousands of barrels in no time. In 1936, they released their high-end National Premium, a pilsner, proudly heralded as “probably the costliest beer brewed in America.”

Two years later came National Bohemian, a lager, first brewed at the original factory in 1885 in the style of a popular beer from Bohemia, now of the present-day Czech Republic, and described with words like “lightness,” “brightness,” and “zest.”

At 10 cents a bottle, it was considered a mighty fine beer—not the second-rate swill some readers might snarkily regard it as today. But its meteoric rise would still not start until the next decade, when, after World War II, a young Jerold Hoffberger would take over the family business, ushering in the era of “Boh.”

National Brewing Company beer in production, circa 1968; the Natty Boh Tower, 1949; a vintage beer can, circa 1950s. —BALTIMORE MUSEUM OF INDUSTRY ARCHIVES; COURTESY OF NATIONAL BOHEMIAN

hatever you think of National Bohemian today, we can all agree on one thing: It’s hard not to like Mr. Boh. Early iterations—usually a slender gentleman with a monocle or top hat—were admittedly more pompous and less lovable. But then came that little fella with a full-moon head and fun-loving personality, somewhere between the Monopoly Man and the more recent Mr. Pringles, calling his catchphrase out into eternity—“Oh boy, what a beer!” Truly, what would the brew even be without its iconic mascot?

In the 1950s, Mr. Boh was born as Mad Men-style genius. The esteemed W.B. Doner advertising agency drew him up, smacked him on the bottle, then featured him dressed as a sailor, a fly-fisherman, a mountain-climber in the local newspapers. He was also the animated star of early radio and television commercials. (YouTube them immediately.)

For a short while, they even stitched his likeness onto the sails of a real-life skipjack that sailed up and down the Chesapeake. Onboard, brewery spokesman Frank Hennessy gave weather and weekend fishing reports live on the local airwaves—all part of another new push, to brand Maryland as the “The Land of Pleasant Living,” forever entangling a taste for the beer with a sense of civic pride. Needless to say, it stuck.

“I remember Saturdays and Sundays, you’d turn on the radio, and Hennessy would be drinking a beer, telling us about how the fish were moving,” says Gundlach. “When I was growing up, in the 1960s, it was always National Beer. It was just everywhere here.”

And nowhere was that more true than at the ballpark.

O's-themed

tallboys at Camden

Yards; a Simpsons-inspired

Boh tattoo; a

medley of merch in

Hampden and Fells.

ational Bohemian has long been synonymous with baseball season in Baltimore, and for decades, Memorial Stadium was Boh Country. Not only was it the beer of choice at the ballpark, with bottles sold alongside the likes of Esskay hot dogs, but throughout both O's and Colts games, a variety of jingles also beckoned Baltimore’s blue-collar base to buy it—You work and work in the broiling sun, yes, you run and run and run until the day is done, but you’re looking forward to the fun, of the bottle of National Beer!

“That’s what I remember,” says Ron Furman, 67, owner of Max’s Taphouse in Fells Point, which, alongside its 100-plus taps of craft beer, has been serving National Bohemian since 1985. “You’d go to Memorial Stadium, and it was, ‘Give me a Boh.’”

And when the Birds won, and broadcaster Chuck Thompson yelled out his signature “Ain’t the beer cold?!” over the roar of applause. Well, as Sun sports columnist Peter Schmuck once put it, “There wasn’t a fan within earshot who couldn’t feel that icy tang in the back of his throat.”

But there was a time not that long ago when you couldn’t find a drop of Boh at Camden Yards. Sure, across the way at Pickles Pub, orange-and-black tallboys were omnipresent. And yet inside the hallowed walls of The Yard, the beer slowly but surely disappeared in 2016. It turned out that the Orioles had gotten pissed off at Pabst, alleging that the Natty Boh parent company was using the team’s trademark without permission, which the then-Los Angeles-based brewer protested with a full-page ad in The Sun.

Not everyone wanted Boh back, though. “It is bullshit,” wrote Brandon Weigel in the City Paper at the time. “Sorry, Mr. Boh, but you lost the right to call Baltimore your home when you stopped brewing your beer here,” before adding the ultimate insult, by referencing another once-hometown favorite that notoriously snuck out of town in the middle of the night: “Y’all are the Baltimore Colts of local beers.”

But then, on a balmy afternoon this past July, National Bohemian was once again being imbibed by Orioles fans, some wearing Cheetos-colored, Mr. Boh-covered, Hawaiian T-shirts. “Nat-ty Bohhh!” sang out one beer vendor to the sing-song-y rhythm of “Let’s go, O's!,” as he slung 16-ounce cans up and down the stands. For the first season in eight years, they were guzzled between runs, raised into the air during homers, then left crushed under seats like peanut shells after we narrowly beat the Yankees, thanks to a two-run double by Cedric Mullins. For now, the ballpark and beer brand had sorted out their differences. (Let’s just forget that we saw the new owners giving a toast with Coors Light on Opening Day.)

Beef aside, there remains one undeniable fact of local sports history: We wouldn’t even have a baseball team if it weren’t for Natty Boh. In 1953, the St. Louis Browns were considering a move to Baltimore when owners of the nearby Washington Senators put up a stink over another Major League roster being just up I-95. In swooped Jerold Hoffberger, offering to have his brewery sponsor the D.C. team.

That same year, Hoffberger became partial owner of the Orioles, and eventually took over as chairman. Under his leadership, the O's would go on to win five American League pennants and two World Series. And, along the way, he would populate the front office with, you guessed it, brewery execs, like National’s head of advertising, former sportswriter Frank Cashen, who, as the team’s vice president, helped assemble its dream lineups— Brooks Robinson, Boog Powell, Jim Palmer, among others.

More than just a figurehead, Hoffberger was a civic leader, donating millions to local institutions. He was also a bit of an everyman, who knew his employees by name, and fostered goodwill wherever he went.

“The first words out of his mouth were: ‘How are you? How’s your family? Is there anything I can do for you?’” remembered late slugger Frank Robinson during his induction into the Hall of Fame, an honor that Hoffberger eventually received himself.

And the same was true at the brewery. “Jerry Hoffberger was the best boss ever,” recalls Gundlach wistfully from atop Natty Boh Tower. “He just treated people right.”

Cans, drafts, and caps at Mt. Royal Tavern, Nacho Mama’s, and Max’s; Boh Tower; and National Premium at Wells.

f course, nothing good lasts forever.

In the 1960s, when Boh boomed in Baltimore, National had become the state’s largest brewery, with outposts in other cities like Detroit, Miami, and Phoenix. Altogether, it made more than two million barrels of beer a year, as well as a wildly popular malt beverage, Colt 45, introduced as a hat tip to local running back Jerry Hill, who wore the number.

Yet all the while, the “King of Beers” was brewing in the Midwest. For years, Budweiser’s Anheuser-Busch had been building larger factories and already expanded nationally, making more and more beer for less and less. Advertising campaigns of the day told the next generation that big suds were in, and before long, American tastes began to believe them.

Just like during the turn of the previous century, local breweries started merging in order to make ends meet. National Brewing had been in the red for years when it consolidated with the parent company of Canada’s Carling Breweries in 1975. They shut down the Canton brewery, moving production to a more modern plant in Halethorpe. Within a few short years, it was sold again, and then again.

Finally, after attempts at an “ice” version—shudder—the last Boh brewed in Baltimore rolled off the line two weeks before Thanksgiving in 1996, meeting a similar fate as the city’s once-prolific Pikesville Rye Whiskey—a shadow of its former self, with production moved out-of-state.

At this point, Boh was no longer just affordable, it was downright cheap, with some saying it was a change you could also taste. Now now the only people drinking the stuff seemed to be hipsters, old-timers, and superfans, like Patrick “Scunny” McCusker in Canton.

A couple years before the beer’s demise, the late Nacho Mama’s owner turned his Mexican restaurant into a shrine to National Bohemian, incorporating Mr. Boh into his own sombrero-ed mascot and covering the place with a panoply of memorabilia. He even retrofitted a 1951 Willys Jeep into a red-and-white Boh-mobile, stitching the character’s likeness into its Italian-leather seats.

“On our wedding day, there was a pail of ice in the limo next to us, full of Natty Boh,” says McCusker’s wife, Jackie, who now runs the business. And when Scunny passed away in 2019? His pallbearers wore T-shirts featuring that one-eyed guy, his lower lid shedding a single tear. “Everybody toasted him with Boh.”

For Baltimoreans like the McCuskers, National Bohemian still put the charm in Charm City. It felt like home. It harkened back to simpler times. It didn’t matter that it wasn’t made here anymore. An affection both ironic and genuine.

“I would hope that the National Boh brand holds, but if it doesn’t, I would like to see one of those small microbreweries pick up the name and brew just enough for the local market—sort of a nostalgic tie-in to the past,” said Hoffberger to The Sun in 1991. “I think Baltimoreans will go for that.”

Five years later, the beer stopped being brewed in Maryland. Then, two months before his death in 1999, it was swallowed up by Pabst.

National Brewing Company executives picking crabs in “Crab Feast,” 1954. —A. Aubrey Bodine

cross the Bay Bridge, down Route 50, on a crumbling driveway at the edge of the Tred Avon River, though, Hoffberger’s dream is being at least partially realized by Tim Miller, who sits in a quiet office, surrounded by artifacts of Baltimore’s brewing past, including a print of that popular A. Aubrey Bodine photograph of National execs picking crabs (pictured above.)

It is here, on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, where the Talbot County native had his first taste of their beer as a kid, brought over by his uncle from Linthicum. And it is here, too, where, years later, he got the wild idea to try and save it.

But in 2010, Miller wasn’t interested in Natty Boh. Instead, the Easton realtor stumbled upon an auction that was selling the trademark for its fancy older sibling, National Premium, which he won for a mere thousand bucks.

“It’s been nothing but strokes of luck,” says Miller, now 56, “which is why I can never give up on it.”

During its prime, National Premium was the Heineken of the day—a dry, crisp pilsner, served everywhere from Haussner’s in Highlandtown to the Plaza Hotel and Waldorf Astoria in New York City. But over time, it lost the spotlight to its little lager brother, being discontinued entirely in 1996.

One attempt at a local revival never took off, and then came Miller, who also owns the rights to Gunther, which he hopes to revive one day. Over months and months, he eventually pieced together the recipe with the help of a retired Carling brewmaster, and by 2012, the inaugural run of the new Premium was made in nearby Delaware. Then, two Octobers ago, it finally returned to Maryland, with the state’s first batch in decades brewed at the Heavy Seas brewery in Halethorpe, just a stone’s throw from National’s last digs.

“It was a no-brainer,” says Hugh Sisson, founder of Heavy Seas and the sort of elder statesman of Baltimore’s craft beer scene. Now, each year, a small-but-mighty volume of Premium is brewed, bottled, and sold across the state, mostly to liquor stores, if you know where to look. (Which Gundlach does; it’s still his favorite.)

When Sisson got started in the 1980s, what were then called microbreweries were just beginning to crop up across the country. Think your Sam Adams and Sierra Nevadas. And so after President Jimmy Carter legalized homebrewing, the Northwood native transformed his family restaurant into Maryland’s first brewpub on Cross Street, then started Clipper City Brewing, which eventually became Heavy Seas.

Before long, dozens of other brewers—now labeled as “craft”—started to follow his lead: Oliver, The Brewer’s Art, Union, Peabody Heights, Diamondback, Waverly, Key, Wet City, Monument City, Checkerspot, Nepenthe, Mobtown, to name a few. By all accounts, brewing was back, baby, and new mainstays emerged, like Heavy Seas’ Loose Cannon, Union’s Duckpin, and Diamondback’s Green Machine, all helping to create local manufacturing jobs and put dollars back into the local economy.

Today, there are at least 100 craft breweries in the state of Maryland alone. And while that might sound exciting, it’s part of a nationally flooded market, with the past few years of beers getting stronger and stranger—featuring over-the-top hops or unlikely flavorings—as everyone tries to outdo each other. Meanwhile, shelf space is shrinking, and as in times past, it’s a boom-turned-bubble that might just burst.

“Everything is cyclical,” says Sisson, 70, comparing the present moment to the late ’90s, when Premium croaked. “I don’t want to wish anyone ill, but there’s too many breweries. We’re already beginning to see some attrition, and I think the industry is maybe a third of the way through a natural Darwinian correction. But we’ve been through this before, followed by a period of growth. The game right now is just do everything you can to survive.”

In large part, that’s because Gen Z is drinking less, if at all these days. Perhaps for their health. Perhaps because of the rise of recreational cannabis. And when they do drink, they like canned cocktails and hard seltzers. As for beer, brewers say lighter options are the new IPAs. In fact, Modelo is the best-selling brew in America right now. And perhaps the Mexican-made pilsner-style lager is trying to tell us something:

Love it or hate it, it might be Boh’s time to shine again.

A six-pack of National Premium at Wells.

n 1999, when Pabst bought out the last owners of National Bohemian, everyone worried about what would become of the once-local beer. Surely, the big company could’ve trimmed the fat, seeing as how even we were barely drinking it. But while sales have indeed declined over time—including an extra dip due to the pandemic—with Pabst, Boh has remained.

Now, ahead of the brand’s 140th anniversary in 2025, there are grand plans for a full-blown revival, one once more riding on Boh’s uncanny ability to invoke local nostalgia. A new can. An LED relighting of the mascot’s sign above Natty Boh Tower. Maybe, one day, even the return of those beloved bottlecap puzzles—remember them?

But it won’t be a walk in the park. “Back in 2013, we were making almost a million cases,” says Nitasha Chopra, Pabst’s brand manager for National Bohemian, noting that current production is closer to 370,000. “We’ve got aspirations to get back to that . . . but we have some work to do.”

Exhibit A: On a hot summer night in the heart of Canton, two twenty-something bros are walking their dogs with happy-hour beers sneakily in hand. White cans. Old-school labels. But not Natty Boh. Miller Lite.

Not that the two products are all that different anymore. In fact, until just a few years ago, they were made at the same facility. Now, Boh comes out of the old Rolling Rock factory in Latrobe, Pennsylvania. But both are light, at about four-percent alcohol by volume. Both are inexpensive, around 10 bucks a 12-pack. Both are comforting in their consistency, kind of like a McDonald’s hamburger. They are those classic, crisp, fizzy, no-frills, nothin’-fancy, yellow beers of every American’s mind’s eye. Like the emoji of a mug cheers.

It used to be said that if you walked into a Baltimore bar, nine of out 10 pints poured were National, with the other being one of those Midwest big guys. And while those numbers have certainly shifted, Boh does stay in rotation and, in plenty of establishments, it is still the bestseller, even above the high-quality craft beer that’s actually made here.

“That’s been somewhat of a challenge,” says Jon Zerivitz, co-founder of Union Craft, who, like other local brewers, would like to see Marylanders spend more of their beer-drinking dollars on truly local options, such as his own light lager, Zadie’s, brewed in Medfield. And yet, the Pikesville native has to admit, “You can’t help but be amazed by the power of their brand. It literally looms large over this city.”

Without a doubt, it’s a love affair founded in both fact and fiction. And yet the latter isn’t stopping fans from flocking for selfies any time the foam-headed, human-performed Mr. Boh shows up at an event, as if he’s some sort of Taylor Swift. And we’d bet good money that every other reader owns a T-shirt declaring that BOH KNOWS, or that this is BOHTIMORE, with Route One Apparel having sold hundreds of thousands of bits of Boh swag over the last decade. After all, a few years ago, when the controversial lyrics of “Maryland, My Maryland” made the rounds on the internet, some even suggested a new state song: National’s old Land of Pleasant Living jingle.

“It’s a Baltimore thing—period,” says Ben Franklin, bartender at Mt. Royal Tavern in Mid-Town Belvedere, where cases get put on hold for former residents when they’re back in town, and about which Esquire magazine once wrote that the go-to order should be “a Natty Boh, a shot of Pikesville, and religious thoughts.”

Of course, if you ever need to find the faith, head to the eastern edge of the city limits, back to the corner of Conkling and Dillon, just past one of those fading “Greatest City in America” benches, to where Gundlach once worked.

There, high above, at the very tippy-top of Natty Boh Tower, a bright light will glow over a lurking figure—a 27-foot floating head, with slicked-back hair and a black handlebar mustache. You know the one. And if somehow you don’t, you can’t miss it.

At 20 years young next month, the Mr. Boh sign is already one of the city’s most iconic landmarks, alongside the likes of the circa-1803 Fort McHenry of circa-1829 Washington Monument. It was erected not long after Obrecht bought the former National buildings in the late 1990s and brought the rest of Brewers Hill back to life in the years that followed—decades after the neighborhood stopped making beer.

For a few years, the mascot’s red neon had stopped winking, but in mid-September, it was replaced by LED lights. And so now as before, every day and night, he continues to keep watch over Baltimore. As if calling out, loud and proud, to all the humans in all the houses, and all the cars on all the highways, and all the airplanes who pass it by at all hours:

That this is a town built on history, and hard work, and a little charm. And that that same spirit has been passed down the generations. Sometimes even literally as an ice-cold thing that you can hold in your own two hands.

“That’s what grounds it here,” says O’Prey. “And my gosh, just driving down I-95 and seeing Mr. Boh—how do you know you’re in Baltimore? Well, there it is.”