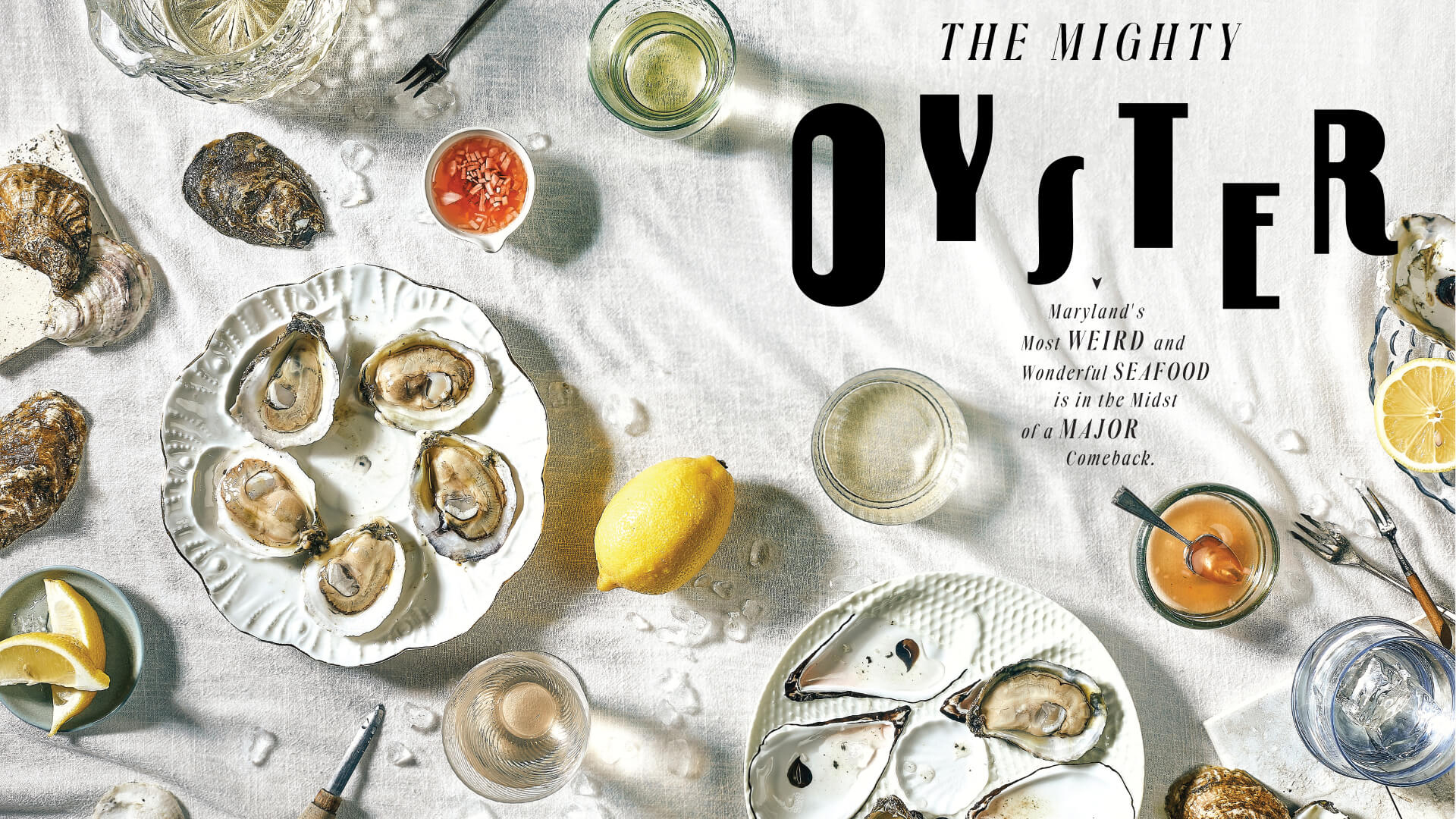

Above: Shells from Johnson Bay, Orchard Point, and True Chesapeake Oyster Co. Shucked by Dylan’s Oyster Cellar. Styling by Limonata Creative

H.L. Mencken was onto something when he declared the Chesapeake Bay the “immense protein factory.” Abundant with marine life, the nation’s largest estuary has fed its inhabitants for millennia. And while there have always been crabs and rockfish, one species in particular has stood out as an especially vital source of edible and ecological significance. Ugly, strange, sexy, controversial—the small but mighty oyster.

We know, we know. They’re not for everyone. But for anyone living in Maryland—let alone in Baltimore, which was once known as Oyster City—the peculiar, polarizing, pivotal creature is more than just a slippery shellfish. In fact, it’s quite worthy of the title “natural wonder:” a tiny filter feeder so environmentally advantageous that it could once clean the entire bay in a matter of days. A teeny reef builder whose homemade habitats provide shelter for other species but also protection from natural disasters and climate change. A tasty specimen of seafood that built towns, ignited wars, and served as an economic powerhouse—forever imprinting on our cuisine and sense of place.

“The largest genuine Maryland oyster—the veritable bivalve of the Chesapeake, still to be had at oyster roasts down the river and at street stands along the wharves—is as large as your open hand,” wrote Mencken in 1913. “A magnificent, matchless reptile! Hard to swallow? Dangerous? Perhaps to the novice, the dastard. But to the veteran of the raw bar, the man of trained and lusty esophagus, a thing of prolonged and kaleidoscopic flavors, a slow slipping saturnalia, a delirium of joy!”

Those mammoth oysters might be a thing of the past, but that enthusiasm—so reflective of the oyster’s reign supreme— is increasingly alive and well throughout Maryland. In truth, the mollusk has been having a bit of a comeback over the past decade, with restoration efforts, restaurant openings, and the rise of aquaculture, aka the farming of oysters, returning the keystone species to its once-iconic status.

“To me, it is a very American story,” says Katie Livie, Chesapeake historian and author of Chesapeake Oysters: The Bay’s Foundation and Future. “American industry, American environmentalism, the American sense that the horizon goes on forever, but also this uniquely American manifest destiny being drawn up short, because apparently forever has an end. It all comes together in the oyster.”

Weird and wonderful, exotic and quotidian, oysters are one of the most valuable chesapeake species—ecologically, economically, and as a part of our identity.

THEY SAY IT WAS a brave man—or woman—who ate the first oyster, and along the Chesapeake, we know that Native Americans were harvesting the bivalves as early as 2500 B.C. By the 1600s A.D., they remained a primary food source, edible on their own, full of protein and nutrients, with colonists often remarking on their size and abundance, with reefs so large they were navigational hazards.

But this simple seafood, until then harvested by hand and consumed locally, would soon undergo a drastic transformation. In the early 1800s, after ravaging their own oyster beds, New England oystermen swept up the bay on big ships hauling newfangled dredges capable of harvesting far more oysters. Within a decade, the machinery was banned, as were visiting watermen, but their arrival had already changed the industry. Three main factors made the oyster boom boom, says Livie: “This incredible oyster population, New England harvesters coming down with huge vessels and dredge technology, and then the growing city of Baltimore.”

The invention of canning in Europe had modernized food preservation, and before long, American entrepreneurs like Caleb Maltby were capitalizing on nearby reefs and the new B&O Railroad, opening Baltimore’s first oyster cannery in 1834. Thanks to its unique position, the city would soon become the canning epicenter of the United States, with more than 100 operations lining the harbor, employing thousands of largely Black and immigrant workers who shucked, steamed, and sealed millions of dollars' worth of oysters to meet America’s insatiable appetite. “They were cheek to jowl along the waterfront, with bugeyes and skipjacks stacked six deep along the bulkheads,” says Livie. “They were the beating heart—this artery of life, money, and industry that really catalyzed Baltimore from this rawboned backwater into the city that it became.”

Unloading oysters in Baltimore, 1905. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

Of course, money has long brought out mankind’s lesser angels. After the Civil War, the “White Gold Rush” turned the bay into a place of pirates, murder, and mayhem. Even with an aquatic police force, the Oyster Wars raged on. “Several deaths caused by violent means,” wrote The New York Times in 1895. But with such demand, with harvests reaching 15 million bushels, came the collapse of the natural resource.

Today, wild oyster populations are estimated to be less than one percent of their historic peaks, due to centuries of overfishing, but also two decimating diseases that arrived in the 1950s, plus pollution and habitat loss. In their void, crabs became king, with Maryland creating a state crustacean, not mollusk, in the 1980s.

This era also brought about a wave of environmental organizations who made it their mission to bring oysters back from the brink. It is said that a single oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of the estuary a day, removing sediment and excess nitrogen, while its reefs, where these stationary creatures live, grow, and reproduce, provide a habitat for other species, buffer for eroding shorelines, and substrate for more oysters. Restoration efforts include both replanting commercial bars and protected sanctuaries. “Oysters are not the savior of the bay, but they are an effective tool with a whole host of ecosystem benefits, and we need all the help we can get,” says Ward Slacum, director of the Oyster Recovery Partnership (ORP), pointing to the need for more comprehensive data on oyster habitat.

Better late than never, the Department of Natural Resources launched Maryland’s first oyster stock assessment in 2018 and, last year, created a revamped Oyster Advisory Commission to advise on fishery management. The state now has around 500 million market-size oysters, its third largest abundance in the past two decades. Maryland’s 1,239 oystermen hauled in 332,946 bushels last season, with both figures increasing in recent years, though still a shadow of their heyday.

A woman eats her first half-shell, 1938. Photo courtesy of A. Aubrey Bodine.

“We scientists call it shifting baselines,” says Mike Roman, director of the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science’s Horn Point Laboratory. “The natural catch is going up, whether it’s from environmental conditions or all the new oysters being put into the bay.”

That said, another potential factor might be the advent of oyster farms, boosted by 2009 legislation to revive the fading wild industry. More and more farmers are using triploid oysters, which, virtually sterile, don’t waste their energy on a summer spawn, thus eliminating the old adage of only eating oysters in winter “R” months and creating a yearround oyster. “Farming, by its nature, is sustainable, as the more you sell, the more you plant,” says Scott Budden of Orchard Point Oyster Co. in Stevensville, an aquaculture operation since 2015. “It helps take the pressure off the wild stock and create somewhat of an equilibrium. We think the two can coexist.”

“Watermen get a bad rap, that we’re just take, take, take,” says Nick Hargrove of Wild Divers Oyster Co. in Wittman, which hand-harvests wild oysters. “But we’re also stewards. We have more dog in this fight than anyone to see more oysters in the bay. That’s our heritage—and we want it to be our future.”

Both parties have their own battles, with the Hogan administration considering new aquaculture restrictions, and comptroller Peter Franchot suggesting the elimination of the wild fishery in its entirety. And all the while, our hunger is only growing, with at least a half-dozen oyster bars opening in Baltimore in recent years. The farmed oyster has become a sort of farm-to-table luxury, but there are still places where you can find them buck-a-shucked, oyster-shootered, slapped on paper plates, or served en masse at bull-and-oyster roasts—then and now, an everyman’s staple.

“When I was little, I’d go to corner bars in the mornings with my friends’ fathers, who’d get raw oysters on the half shell with a pint of beer—a Chesapeake breakfast,” says chef John Shields, who serves them atop eggs Benedict at his restaurant, Gertrude’s. “What makes our oysters so special is our huge estuary, this brackish water, that mix of salt and sweet. I look at their liquor like culinary gold.”

Weird and wonderful, exotic and quotidian, oysters remain one of the most valuable species on the Chesapeake— ecologically, economically, and as a part of our identity. This is, after all, a place where antique cans have become collector’s items, where white-sailed skipjacks remain a state symbol, and where every autumn, after our last crab feast, we can feel that primal shift in our bones: Onward, to oysters!

“There’s been this beautiful dance going on between one humble resource and people’s lives for thousands of years,” says Livie. “It’s an ongoing story. But it really comes down to this simple appreciation of the bay, encapsulated in one little shell. You have the opportunity to savor the entire history of the Chesapeake every time you eat one.”

A brief BIVALVE education.

What is it that makes the oyster so alluring? To the unknowing eye, they’re unglamorous blobs, but these tiny creatures are full of mystery and magic, in that each one contains both the ability to clean waterways and provide humans with a whole, healthy, ready-to-eat piece of protein—all packed into one little shell. Get to know what you’re working with before you start slurping, beginning with their biology.

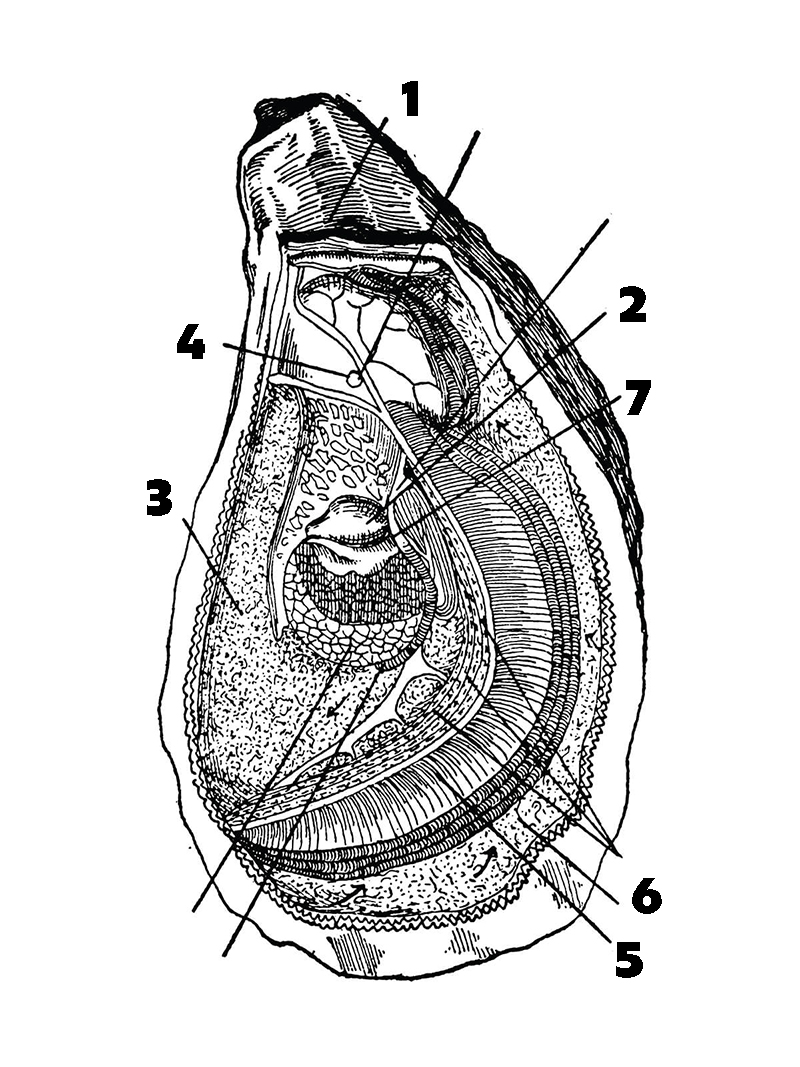

With a hinged shell (1), oysters are a bivalve-type mollusk that begins life as microscopic larvae that attaches to an underwater surface, such as other oyster shells, often forming oyster reefs where they’ll live out their entire lives. There are five oyster species harvested in North America, including the Crassotrea virginica, native to the Chesapeake Bay and Atlantic Coast for at least tens of thousands of years.

Oysters are not just one big muscle. They are full of organs—hearts (2) and stomachs (3) and private parts (4)—and, as filter feeders, their gills (5), through which water is pumped and algae, or phytoplankton, is captured for food, are their largest organ. The gills also trap calcium carbonate to help them grow their shell, which is the main job of the mantle (6), in addition to holding everything together. It is attached to the adductor muscle (7), which allows them to open and shut.

Still one more important fact: More than 95 percent of the oysters we now consume are actually farm-raised. They are grown loose on the creek or river bottom, or, increasingly, in cages, floats, or bags attached to buoys in the open water. Read on for one key difference between wild and farmed oysters.

F.A.Q.

WE ANSWER SOME BURNING QUESTIONS.

Lewis Carroll’s The Walrus & the Carpenter —Creative Commons

Can I only eat oysters in “R”

months?

The short answer is

no, but that wasn’t always the

case. The legal harvest season

for wild oysters in the state of

Maryland runs from October

through March, aka most “R”

months. The old adage refers to

the fact that oysters spawn in

summer, leaving their flesh weak

and undesirable to eat, but also

dates back to the days before

refrigeration, when oysters could

spoil in warm temperatures

before they ever made it to market.

Luckily, we now have air-conditioning,

and many farmed oysters, like many of

the ones you see in restaurants,

have been bred to be virtually

sterile, meaning they don’t waste

energy on reproduction and thus

are edible year-round.

◆

Wait, what do you mean

they’re sterile?

Don’t freak

out. This is not some Frankenstein-like

genetically modified organism,

engineered by the

transplanting of genes from

one place to another, like in

so much corn and soybean

production. Instead, it’s the

same thing as a seedless

watermelon, as well as most

bananas and blueberries.

Like these fruits, farmed

oysters are selectively bred

to be triploids, meaning they

have three sets of chromosomes

instead of two. This

means they don’t reproduce,

which for the above reasons

yields a more desirable food.

An age-old farming practice.

◆

But are they the same

oyster?

Yes, they are the

same species and provide

the same water quality

benefits as their wild counterparts,

while also helping

to meet the global demand

for seafood and encourage a

sustainable fishery.

◆

Are oysters aphrodisiacs?

Sorry, probably not. This

myth dates back to the

Roman Empire, only aided by

Italian adventurer Casanova,

who was said to have credited

his notorious libido to

eating 50 oysters for breakfast.

So far, there is no science

to connect their consumption

with the stimulation of desire.

◆

Do they really make pearls?

Yes! Though rarely in the ones

you eat. Pearls are essentially

a form of self-defense: when

a foreign substance such as a

grain of sand gets stuck inside

the oyster, it covers the irritant

with a protective coating

made out of the same material

used to create its shell.

Eventually this forms that

coveted iridescent treasure.

VINTAGE PLATES CAPTURE THE PAST POSH STATUS OF OYSTERS. Photography by Justin Tsucalas

One MARYLANDER’S path toward LOVING half-shells.

I’ll admit it: Even as a native daughter of the Chesapeake Bay, I didn’t eat an oyster until the 21st year of my life. And in New York City, of all places. Sort of a sacrilege, I know. “You’re from Maryland, and you’ve never had an oyster?” asked the Grand Central Oyster Bar waiter in disbelief. I can’t tell you where the oyster was from, or how much cocktail sauce it was quickly slathered in, but I do know that I shut my eyes and threw it down my gullet and, after surviving, thought: “That wasn’t so bad.” In fact, it was kind of good. Before long, I upgraded to mignonette, and then just a squeeze of lemon, and over time, I came to understand that there are few greater delicacies than a freshly shucked raw oyster. It is simply incredible that nature made this itty bitty piece of perfectly imperfect protein, and that, by some miracle, a human being figured out how to open its rock-like shell (and then actually had the cojones to eat it). Not to mention that when you do, you can literally taste the nuances of the waters it came from, even varying from creek to creek. For all of this, I finally worked my way up to a practice instilled by other purists: Every time I sit down to new oysters, I eat my first plain, naked, straight up. Out of sheer respect. In pursuit of curiosity. In the presence of wonder and awe. Garnishes can come afterwards. But for one beautiful second, it’s like swimming. —LW

A medley of Johnson Bay, Orchard Point, and True Chesapeake oysters, all grown in Maryland. Photography by Christopher Myers

How to Shuck an Oyster

Shucking can be intimidating, but consider it a life skill, whether stranded on a desert island or spending a Saturday afternoon with friends. All you really need are oysters, an oyster knife, and a little courage to begin.

Illustrations by Disha Sharma

1.

Place oyster on a bar towel, with cup down and hinge toward you.

2.

With non-dominant hand, hold down oyster shell. With dominant hand, place tip of knife into hinge, parallel with top shell, applying slight pressure to wedge tip inside.

3.

Once in, wiggle knife clockwise or counterclockwise until top shell pops. Slide blade along the side of hinge to bill. Discard top shell.

4.

Slide blade beneath oyster to slice adductor muscle and release from shell. Slurp plain or topped with accoutrements.

TOOLS of the TRADE

If we had our druthers, every party would be equipped with a DIY oyster station. Gather round, crack a few open, and let the world feel like your, well, you know.

- DRINKS. Oysters pair well with Champagne, dry white wines, and a spectrum of beers, from Irish stouts to pale ales. We even once enjoyed them with a “spaghett,” aka the viral Miller High Life and Aperol cocktail invented by Baltimore’s own Wet City. We even like them with a “spaghett,” the Miller High Life and Aperol cocktail by Baltimore’s Wet City.

- KNIFE. A proper oyster knife is essential. No butter knives, no steak knives, no screwdrivers. Order one online, like this “Chesapeake stabber”-style version, and save yourself the injury. R. Murphy makes a beautiful blade.

- SHUCKING BOARD. Oysters can truly be shucked anywhere—benches, tailgates, on top of coolers—but having a sturdy piece of wood beneath you can help reduce the slipperiness of especially tricky shells.

- BAR TOWEL. Any old rag will do. Just use it to secure the oyster and protect your hand.

- LEMON.The acidity of the citrus balances and enhances the seafood’s briny flavor. Add a squeeze before you slurp.

- MIGNONETTE. Move over, cocktail sauce. This French mixture of vinegar, pinched shallot, and black pepper adds a dynamic punch to oysters without masking their natural flavor. Make your own at home with a few sprigs of fresh thyme.

- HOT SAUCE. Always keep a bottle of Woodberry Pantry’s smokey Snake Oil Hot Sauce at the ready, fittingly made with Chesapeake-grown fish peppers.

HOW ELSE WE LOVE TO EAT THEM

Illustrations by Disha Sharma

Rockefeller:

Oysters Rockefeller

is a roasted category

unto itself—a timeless

classic whose

original recipe,

invented in New

Orleans in 1899,

remains somewhat

of a mystery. All we

know is the combination

of spinach,

Pernod, and breadcrumbs

is truly hard

to beat.

TRY THEM AT:

Loch Bar, 240 International

Dr.

Roasted:

There’s

no wrong way to roast

an oyster. Throw

them on a grill,

over a fire, or in the

oven—either plain,

to be eaten with the

likes of garlic-parsley

butter, or topped with

an array of accoutrements,

like parmesan

and bacon. Medium

oysters work best

for a slightly bigger

vessel.

TRY THEM AT:

Woodberry Kitchen,

2010 Clipper Park Rd.

Fried:

We will

always have a soft

spot for fried seafood,

and this Chesapeake

comfort-food staple

is a solid route for

bivalve beginners. A

light, crisp, golden-brown

batter allows

that salty-sweet flavor

to shine through, but

without the slippery

texture that scares so

many off. Trust us and dip ’em in

remoulade.

TRY THEM

AT: Charleston, 1000

Lancaster St.

Stewed:

At least

one cold fall or winter

night, you should treat

yourself to oyster stew.

The old-fashioned soup

is a decadently simple

mix of butter, cream,

celery, and onion with

a few cooked oysters

and usually other family

secrets. Top with a

touch of hot sauce and

a handful of classic

oyster crackers.

TRY IT

AT: Gertrude’s Chesapeake

Kitchen, 10 Art

Museum Dr.

A day in the LIFE of GROWING oysters on the Chesapeake.

Ryan Brown carries oysters at True Chesapeake. Photography by Christopher Myers

AT THE END OF AUGUST, white workboats are an iconic sight of Maryland summer, speckling the waters of the Chesapeake in search of the season’s signature big, fat blue crabs. But not on a quiet cove along the edge of St. Jerome Creek in Southern Maryland, where on this bright blue morning—the mercury already climbing into the nineties—Ryan Brown is forearms deep in something long associated with the winter months: oysters.

Baby oysters, to be exact, with each of these tiny shells arriving like a grain of sand at a mere one millimeter to the True Chesapeake Oyster Company just outside of St. Mary’s. Here, in the shaded outdoor nursery, they will be tended to for weeks to months—fed algae-rich creek water, transitioned into larger tanks, and then, eventually, when they’re big enough, moved out in submerged pods along the shoreline, ultimately ending up in galvanized cages in the open water.

St. Jerome Creek. Photography by Christopher Myers

“A lot more goes into this than people realize,” says Brown, 37, who, as farm manager, oversees the life cycle of every oyster at True Chesapeake, now one of the largest operations of its kind in the state. “It takes two full years to sell an oyster, and it’s pretty neat to stand back and see all the work you’ve done.”

More than 95 percent of the oysters we eat are now farm-raised using aquaculture, aka the centuries-old practice of farming aquatic life. Be they hobbyists or career farmers, there are now 178 oyster leaseholders in Maryland. They total some 7,512 acres, 10 of which are True Chesapeake’s. Each operation is slightly different, from protected coves to the open bay, using cages on the bottom sediment or floats on the water’s surface.

“If we started looking at the bay as an economic engine that can coexist with the ecosystem, we’d have a healthier bay.”

“There’s no book on it—you just learn as you go,” says Brown, steering the boat out toward a network of buoyed lines, each dangling with about 75 cages, which are hauled up using a hydraulic winder and back to the dock to be sorted by size, then redeployed into the creek or harvested for market. It’s physical work, done through hurricanes and winter hail, “like mailmen,” says Brown, whose tanned skin and scruffy beard tell of the many hours spent out on the water.

He first learned about oysters more than 100 miles north of here, at the Nickel Taphouse in Mt. Washington, where he helped shuck oysters behind the raw bar. Through a mutual friend, he was introduced to True Chesapeake owner Patrick Hudson, coming on board full-time not long after a farm visit in 2015.

“He’s now the muscle and brains behind the farm these days,” says Hudson, who founded True Chesapeake in 2012 with his father, Patrick Sr., a bay pilot in nearby Solomons Island. “Oyster farming is tough, but every year is a new opportunity.”

Scenes from True Chesapeake: the nursery, sorting shells. Photography by Christopher Myers

A number of obstacles hold back a booming aquaculture industry, from the cumbersome lease approval process to community protests by neighbors or watermen, to the sizable upfront investment required—not to mention breaking your way into the market and dealing with Mother Nature. Hudson recalls one particular supermoon-fueled nor’easter whose extremely low tides left them with hundreds of thousands of dead oysters. Then, of course, there was the coronavirus, which hammered the hospitality industry—an oyster farm’s bread and butter.

“Overnight, our sales fell 100 percent,” says Hudson, whose Skinny Dipper and Huckleberry varieties are sold at more than 60 regional restaurants—including their own—plus gourmet grocers such as Whole Foods and MOM’s Organic Markets, which helped them weather the pandemic.

Since this spring, when vaccinations allowed restaurants to begin reopening in earnest, demand has rebounded quickly, continuing its upward trend as shown over the past decade. “There are more seafood restaurants and oyster bars and in general a more informed public,” says Hudson. “New demographics are beginning to eat oysters and are also becoming more environmentally aware,” connecting the dots between aquaculture and a healthy ecosystem.

Hauling oysters. Photography by Christopher Myers

Just like their wild counterparts, farm-raised oysters improve their local water quality, while also easing pressure on the estuary’s depleted populations and promoting a sustainable fishery, thanks in part to the advent of the year-round triploid oyster. Hudson hopes a generational shift will continue to push this education, and his industry, forward.

“When young people look out and see these buoys in St. Jerome Creek, they think, something cool is happening here,” he says. “Culturally, we look at the Chesapeake Bay as a luxury—a view. If we started to look at it instead as an economic engine that can coexist with the ecosystem and provide quality food, imagine what things would look like. You’d see more oysters in the market. More Ryans in the industry. And we’d have a healthier Chesapeake Bay.”

When did oyster bars become the coolest places to eat? Over the past few years, these seafood spots have crept their way onto lists of the hippest dining establishments, and for good reason. Like oysters, they’re the just-right mix of no-frills and fancy, encouraging a way of eating that’s steeped in nostalgia, supportive of the farm-to-table movement, and features a central communal dining space around which friends and strangers can come together even in divisive times. It’s a trend we hope is here to stay. Order a dozen—or few—at any of these city favorites.

Ready for service at Dylan’s. Photography by Christopher Myers

DYLAN’S OYSTER CELLAR

Hampden

The perfect oyster bar exists on a quiet corner in Hampden, where a mermaid mural mingles with a half-shell-eating Jesus collage and, in non-COVID times, happy hour includes Natty Boh tallboys and buck-a-shuck specials from their thoughtfully curated selection. Owners Dylan and Irene Salmon live up to their seafoody last name. 3601 Chestnut Ave.

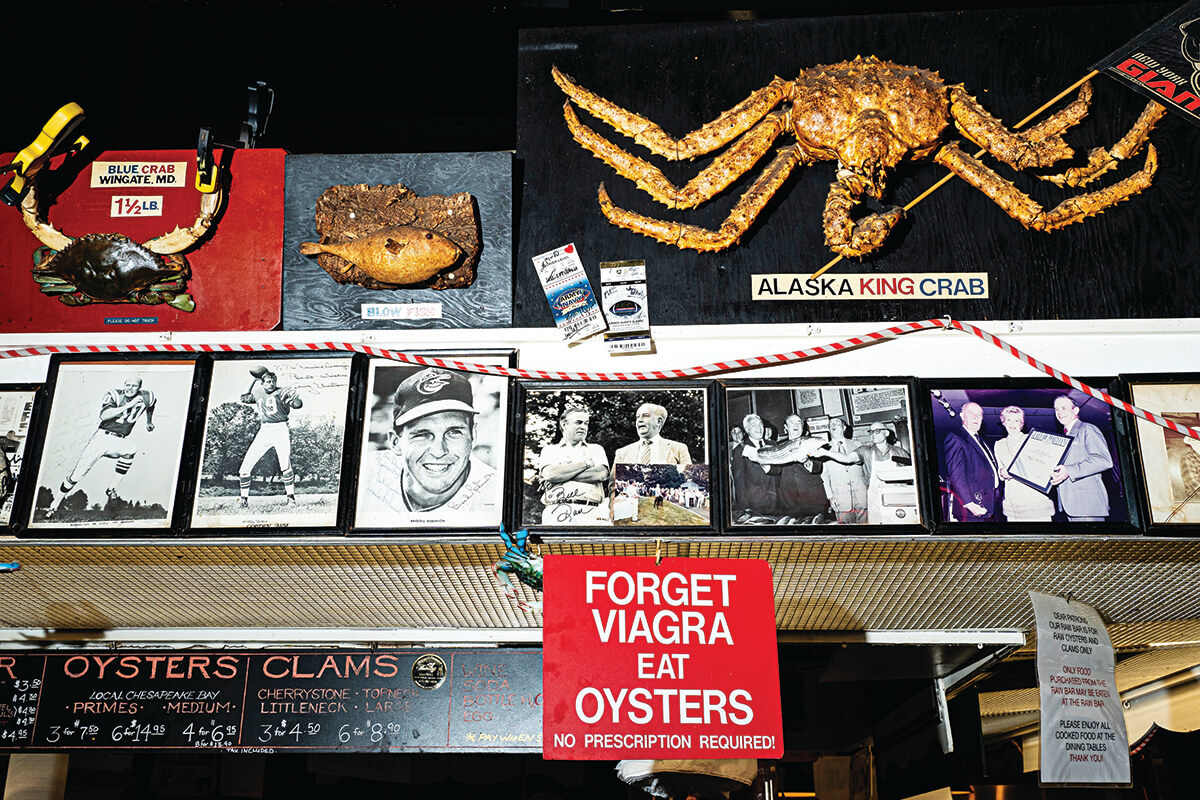

FAIDLEY SEAFOOD

Downtown

It is a rite of passage to sit down to a paper plate of fat half-shells at the central raw bar of this O.G. seafood establishment in Lexington Market. In ole Bawlmer fashion, they serve them on the “flats,” or top shell, with lemon and a pack of Saltines. Order a beer, and be sure to chat up Lou if he’s your shucker. 203 N. Paca St.

THE LOCAL OYSTER

Mt. Vernon

From shucking on the city streets to a brick-and-mortar at Mount Vernon Marketplace (plus a new location coming soon), the L.O.’s beloved bivalve slinger Nick Schauman has played a vital part in making oysters cool again in Baltimore, with his casual bar being one of the best hangouts in town. 520 Park Ave.

MAMA’S ON THE HALF SHELL

Canton

Now in its 18th year, this Canton corner bar has become a Baltimore classic, with weekend afternoons usually overflowing with locals who have flocked for oysters nearly every way you can eat them, alongside freshly squeezed orange crushes and Orioles and Ravens games on the TV. An ideal Saturday afternoon. 2901 O’Donnell St.

THAMES STREET OYSTER HOUSE

Fells Point

For a while, this Fells Point seafood haven was the only game in town serving up fine-dining flights of oysters, but even as new spots have come onto the scene, theirs remain some of the cleanest shucks around. Their impressive oyster list includes top varieties from Canada to the West Coast. 1728 Thames St.

TRUE CHESAPEAKE OYSTER CO.

Hampden

The only oyster farm-owned restaurant in the state, this Whitehall Mill pillar is the outpost of its namesake aquaculture operation. Their Southern Maryland-raised Skinny Dipper and Huckleberry oysters are always hawked at their sleek bar, alongside elevated Chesapeake cuisine by locally loved chef Zack Mills. 3300 Clipper Mill Rd.

THE URBAN OYSTER

Mobile Pop-Up

Currently operating on a mobile basis, this Blackowned oyster pop-up can be found at the Baltimore Farmers Market on Sundays. It’s always worth waiting in line for chef Jasmine Norton’s fan-favorite chargrilled oysters, featuring flavor variations like barbecue-bacon-cheddar and teriyaki. Holliday & Saratoga Sts.

FARTHER AFIELD: Ryleigh’s Oyster, Lutherville-Timonium; The Curious Oyster, Nottingham; Sailor Oyster Bar, Annapolis; Old Ebbitt Grill, Washington, D.C.; Pearl Dive, Washington, D.C.; Ruse, St. Michaels.

In action at the raw bar at Thames Street Oyster House, and classic signage at Faidley Seafood. Photography by Christopher Myers and Scott Suchman, respectively

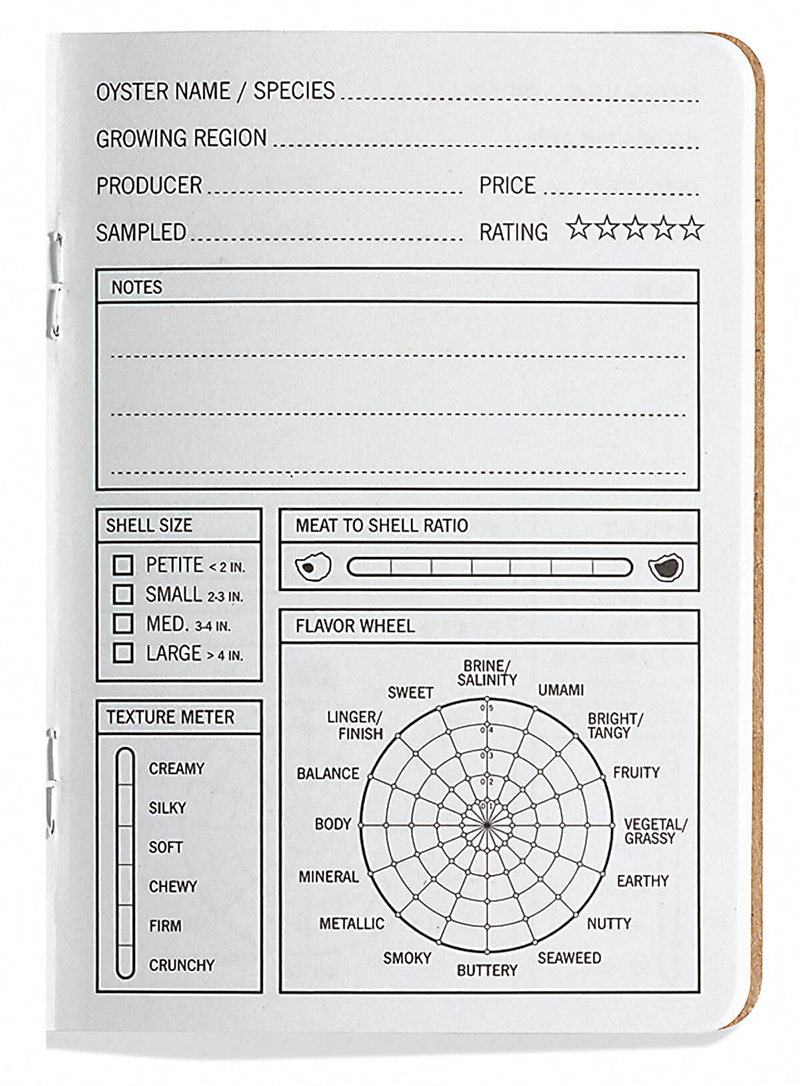

Tasting Notes

CREATE A CATALOGUE OF YOUR BEST-LOVED BIVALVES.

Oysters are like snowflakes. Every variety is different, with a vast range of flavor profiles dependent upon where each hails from, be it West Coast sweets or East Coast salties, with distinct nuances even noticed up and down the individual tributaries of the Chesapeake Bay. Much like a wine’s terroir, the “merroir,” inspired by the French mer for sea, is the many ways in which an oyster’s sense of place—the climate, the currents, the water quality—contribute to its unique taste. We like to keep tabs on our favorites with this handy chart by In A Half Shell’s oyster guru Julie Qiu, in collaboration with 33 Books Co.

PRO TIP: The farther south you go down the bay, the brinier the bivalve. Photography by Steve Temple

GameChanger:

Imani Black

We catch up with the founder of Minorities in Aquaculture.

Photography by Mike Morgan

Thanks to global demand, aquaculture, aka the farming of seafood, has quickly become the world’s fastest growing food system, and Eastern Shore native Imani Black is working to ensure that more minorities are included in the conversation. An alum of the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF), Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS), and currently a faculty research assistant at the University of Maryland’s Horn Point Laboratory, the 26-year-old oyster farmer has launched a nonprofit aimed at nurturing a more diverse and inclusive industry, while also honoring the historic contributions of African Americans on the Chesapeake Bay.

What was your first connection to the water?

Since childhood, my family and I would always go down to the Chestertown wharf [on the Eastern Shore] and fish on Sundays after church. When I was seven, I went to an overnight environmental science camp at the Horn Point Laboratory [of the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science in Cambridge]. We learned all about striped bass, blue crabs, oysters, submerged aquatic vegetation. I was an active kid who loved being outside and on the water. I just understood it. From there, I got into 4-H and community cleanups and volunteering, and it just stuck with me.

You graduated with a degree in marine biology at the Old Dominion University in Virginia before pursuing a career in aquaculture, working with two strong women-led teams at CBF and VIMS. When did you connect that there were still not enough women, let alone women of color, in this industry?

After college, I worked at an oyster farm in Virginia and got smacked in the face being the only woman. I was coming out of playing Division 1 lacrosse, but I’d be carrying totes from one end of the dock to the other and three guys would be like, “Oh no, no, that’s too heavy.” The owner would say, all hands on deck, but not you, this is a man’s job.

It was frustrating. The only other people of color I saw were Hispanic and African-American men who were laborers on the farm. I had just one girl of color in my marine classes in college. But growing up on the Eastern Shore, I was the token Black girl most of the times. My lacrosse team was white. My coaches were white. My teachers were white. I was comfortable in that role. It didn’t affect me until later on.

What made you start to see it differently?

Because I’d been the token, I never really wanted to call things racist. If somebody was being a certain way, I’d be like, maybe they’re just having a bad day. But eventually I got to the place [in my career] where I’d done all I could do, been a great employee, showed up my best, worked on myself, and still kept hitting walls. That’s when I really had to be like, okay, maybe…

When did the idea for Minorities in Aquaculture come about?

I actually had the semi-idea last January. I had seen this Netflix show, Chef’s Table, with Mashama Bailey, a Black chef in Savannah, Georgia, who converted a once-segregated Greyhound bus station into a five-star gourmet restaurant. In her episode, there are two Black oyster farmers, which was the first time I’d ever seen a Black-owned oyster farm. I asked myself when the last time was that I saw a person of color in a leadership role in aquaculture.

Then May came. Ahmaud Arbery was probably the one that really shifted my view, because when I found out, I had just gotten back from a jog. It became so real. The few in our industry who put out statements [following the death of George Floyd] talked about conferences and forums to make aquaculture more diverse. I thought, what are people who don’t even look like me going to do? A lot of Black scientists had the same thought at the same time, with like 12 organizations being formed last summer. Black By Nature. Black Birders. Black in Marine Science. I knew when I started MIA that it was a lot bigger than me. And if you don’t do it, who’s going to?

What are some of the biggest obstacles for minorities entering marine sciences?

Exposure. A lot of people, let alone people of color, don’t know what aquaculture is. They don’t know that more than 50 percent of the seafood that we eat is farm raised. And when you’re not from an area that has a connection to the water, how can we ever expect you to? We can’t ask people to be biologists or conservationists if they don’t understand their environment.

Also, representation. I had an interview at the Hudson Valley Steelhead Trout Farm facility in upstate New York and saw one Black lady who worked there. When I got the job, I took every chance I could get to talk to her. I can only imagine what more experiences like that would mean for the industry.

What has it been like to find resources and even members for MIA?

Super hard. People generally think there’s some list of Black women that I have in my back pocket. I’m like, do you know any black women? Please, give them my name! We’re starting from the ground up with a few PhD students. We can support their research and be a soundboard. Right now, we’re looking at battling some of the obstacles they face in this industry.

You’ve also been diving into the history of Black watermen on the Chesapeake, which includes your own family. How have you gone about your research?

I first learned about Kermit Travers—this highly respected Black skipjack captain from Blackwater, where I had been driving every single day for work. Then I came across Vincent Leggett and his Blacks of the Chesapeake organization, where I really learned from his writing about where we had been and what we had done.

I’m not doing something new; I’m doing something that was a part of my family and so many other people’s families for centuries. There are 12 active Black captains on the Chesapeake today, all over the age of 60, and we used to have 900. This is a part of our history that’s actively dying, and there have been thousands of stories of Black watermen that have never been written. It’s about getting more people of color involved, but also preserving this history.

Inside Maryland’s MAD-SCIENCE oyster hatchery.

Oyster “spat.” Photography by Christopher Myers

DOWN A LONG, TREE-LINED drive along the Choptank River on Maryland’s Eastern Shore stands one of the nation’s leading experts in all things aquatic science. Across its 800-acre campus in Cambridge, the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science’s Horn Point Laboratory produces renowned research on the organisms of the Chesapeake—perhaps none more than its native oyster, which once thrived along these shorelines.

“It’s said that once upon a time, there were enough oysters to filter the entire bay in three days,” says Mike Roman, Horn Point’s director. “Today, we have less than one percent of what we used to.”

Which is why they’re here. Inside the teal-tinged central building, hallways lead past some of the lab’s 125-person staff—research scientists, professors, and students all with different projects underway, from measuring the impact of low water salinities on oyster mortality, a concern amplified by the wetter springs of climate change, to prototyping manmade reefs to combat the eroding shorelines of sea-level rise. Eventually you reach its pièce de résistance in the northwest corner, in a series of rooms that make up the oyster hatchery.

“Once upon a time, there were enough oysters to filter the entire bay in three days.”

“It looks like a microbrewery, doesn’t it?,” says Roman, standing amidst tanks and whiteboards and below a ceiling crisscrossed with some six miles of pipe carrying several kinds of water.

This is where the magic happens. One of the largest of its kind on the East Coast, the state-of-the-art facility is essentially an oyster factory, where, every year, they raise billions of oyster larvae, all of which will eventually end up back in the bay, with a goal of restoring its historic reefs and stabilizing its depleted wild oysters.

Algae starters Photography by Christopher Myers

It all begins in one otherwise ordinary lab room. Here, the broodstock—aka parent oysters pulled from the wild during the winter months—are kept in temperature-controlled water that encourages them to reproduce. A controlled environment is key for the scientists, because oysters spawn externally, meaning that both eggs and sperm are released and fertilized in the open water. Just before the big moment, staff separate the oysters by sex, catch their respective reproductive cells, mix them in a plastic bucket, and, however unromantically—voilà— conception. Before long, the fertilized eggs will develop into larvae.

“We have an entire cafeteria kitchen where we’re growing food to feed them,” says hatchery manager Stephanie Alexander, walking into a small side lab equipped with bright lights, computer screens, and dozens of 20-liter carboys full of colorful shades of algae. Like a beer or sourdough starter, it will eventually be inoculated into larger quantities, filling chambers the size of spacious hot tubs in the outdoor greenhouse.

Multiple times a day, algae is piped back into the building through an automated system that will feed the larvae that now reside inside 10,000-gallon tanks in the main nursery, where they’ll develop for about two weeks. Around this time, they are ready to become juveniles, or “spat,” which they do by attaching to a hard surface, such as other oyster shells. “There’s a lot that goes into it,” says Alexander. “All we’re really trying to do is make more oysters, and then get them out into the water.”

Organizing broodstock Photography by Christopher Myers

A short golf cart ride to the water’s edge, the hatchery’s pier protrudes out into the brackish Choptank, seemingly a world away from the Route 50 bridge right up the river that brims with cars bound for Ocean City.

“Welcome to Jellyfish Acres,” she says, gesturing toward the demonstration aquaculture farm below that has recently been riddled with late-summer sea nettles. All around her, 52 setting tanks sit like above-ground swimming pools, some 12 feet in diameter. Each can hold about 100,000 shells—recycled from residents, restaurants, and shucking houses around the bay by the Oyster Recovery Partnership—onto which the spat will be set. In one week, the connected “spat-on-shell” will be hauled into a conveyor belt, onto a buyboat, and then down the bay to public and protected oyster reefs. The hope is that they will grow into adult oysters that eventually reproduce themselves.

Alexander has been involved in these efforts since arriving at Horn Point in 1996, just as oyster restoration began in earnest on the Chesapeake. Three years prior, after decades of wild population decline, the state of Maryland convened an Oyster Roundtable, with 40 stakeholders devising an action plan that would jumpstart both the hatchery and ORP, which houses its massive mountain of shell on site. “Our job is to help Mother Nature get to a place where she can stabilize and sustain on her own,” says Alexander. “I don’t think we’re ever going to get back to where we were—the world has just changed too much, there’s too much human interaction with the water, the sediment, habitat loss, harvesting. But I like to be optimistic. It’s really going to take all of us working together to solve this.”

The waterfront setting tanks. Photography by Christopher Myers

One especially notable project has been in the works since 2010, when President Obama issued an executive order that would include restoring oysters in 10 bay tributaries by 2025, five of which are in Maryland. With the help of partners such as the Department of Natural Resources, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, restoration projects have since been completed in nearby Harris Creek and the Little Choptank River, with the Tred Avon River wrapping up this year and plans now finalized for the St. Mary’s and Manokin rivers. There’s a chance, says Roman, that without this work, the wild oyster harvest would’ve been shut down long ago.

“Oysters are the vital keystone species—historically, they were the kidneys of the Chesapeake,” says Alexander. “I want them to exist into the future. I want my kids to see them. And I can honestly say, when I go home at the end of the day, that I make a difference. ‘Save The Bay,’ you know?”

Shell Scholar

FIVE MINUTES WITH KATE LIVIE, BONA FIDE BIVALVE EXPERT AND BAY HISTORIAN.

First oyster memory?

On Thanksgiving, my

pop-pop would set a

bushel of oysters on

the picnic table out

back. When you’re

young, you don’t have

a sense of squeamishness.

He’d shuck them

with an old iron shucking

knife, lay them out, and

you’d just get baby

birded, having oysters

thrown down your

throat. It was the best.

Favorite way to eat

them?

Shucking them

on the half shell at

home, with mignonette

because it perfectly

complements the natural

briny flavor. It’s an

old way of enjoying

them—even in Lewis

Carroll’s Through the

Looking-Glass, the oysters

are dancing with

vinegar and pepper.

Biggest slurping pet

peeve?

When people

treat it like it’s a loogie

they have to swallow—like it’s a dare. You’ll

never really taste it

unless you chew it.

Most frequently asked

question?

“How can we

eat them if they’re filter

feeders?” There’s

concern that eating

oysters is like licking

your A.C. They don’t

really have an organ

like a liver; they’re

essentially one tiny

intestine attached

to a mouth and anus.

Oysters can’t digest

sediment, which is a

carrier for pollutants

like phosphorous and

nitrogen, so they ultimately

spit it out as

pseudofeces. What

you’re consuming

is nominal.

Favorite fun fact?

I like to tell students

that oysters have the

ability to change sex

based on their density

and probability of

reproduction. They’re

fluid, so if there are

more female oysters,

some will decide to

become males, and

vice versa, then

back again.

What else makes them

special?

Oysters can

also live up to 20

years in the wild. They

grow about an inch a

year, so early explorers

documented some

that were as long as

your foot. That’s why

they were preferred

for a survival food.

One will fill you up,

and you didn’t even

have to chase it.

Citizen Science

YOU, TOO, CAN SAVE THE BAY—ONE OYSTER AT A TIME.

SAVE YOUR SHELL

ORP has created a Shell Recycling Alliance, with discarded shells from 300-plus restaurants throughout the watershed, including 45 in Baltimore, redeployed onto Chesapeake oyster reefs. Home shuckers can also utilize some 70 public drop-off sites for the remnants of their feasts.

GROW YOUR OWN

Own a waterfront home? Want to feel like an oyster farmer without all the hassle? There are multiple ways to get involved, thanks to “oyster garden” programs through ORP and Chesapeake Bay Foundation, through which citizens can grow their own spat-stocked cages that will then be emptied onto sanctuaries throughout the state.

VOLUNTEER

A collaboration between CBF and the Waterfront Partnership’s Healthy Harbor Initiative, the Great Baltimore Oyster Partnership offers regular volunteer opportunities in Baltimore City, like building, filling, and planting oyster cages at Canton’s Lighthouse Point Marina on October 2. Masks are required. Ages 10 and up.

CLEAN WATER

The future of oysters begins with the water, and there are everyday ways to help protect the estuary. Pick up trash, in your own neighborhood or through stream cleanups. Limit pollutants by skipping lawn fertilizer or supporting local farms that use fewer chemicals. Reduce runoff by installing rain barrels or planting native gardens. And best of all, get out on the bay and appreciate it.