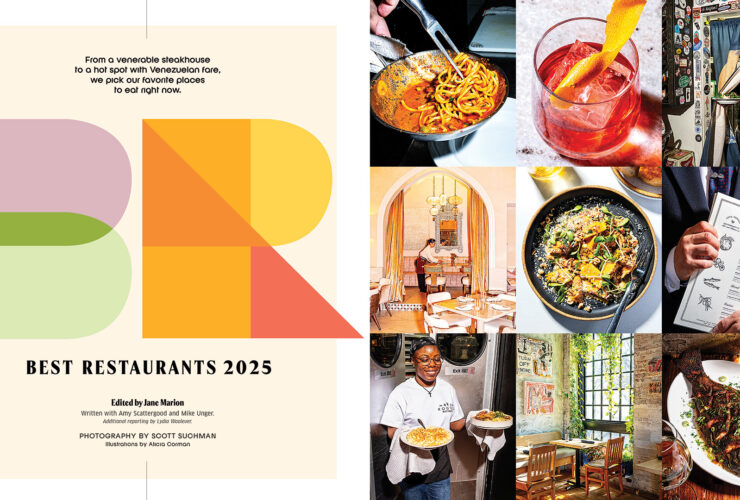

Prime Time

The Prime Rib celebrates 50 years of business in Baltimore.

The Prime Rib owner Buzz Beler.

A minute before five, a dapper man holds open the glass front door for a woman and two teenagers—a lanky boy who doesn’t quite fill out his suit and a girl in heels moving with the grace of a newborn giraffe. Whatever the occasion, it’s clearly a special one, as evidenced by the fact that this group is celebrating at the restaurant where Baltimoreans have marked rites of passage for a half century: The Prime Rib. Five minutes later, Joanne Lindberg and Patti Raley walk through those same doors. They’re promptly greeted with kisses by the tuxedoed staff whose service sets the standard in Charm City. Evening cocktails and dinner at the venerable Mt. Vernon steakhouse isn’t a once-a-year treat for these sisters, but rather a beloved routine. By the time they make their way to their stools, bartender Dan Burks has Lindberg’s Stoli on the rocks and Raley’s whiskey sour waiting. “I’ve been coming here for 40 years,” Lindberg says. “The food is always great, but more than that, I come in and people know me. Even though it’s a fancy restaurant, it’s home. Five years ago, when my husband died, 10 waiters and the general manager and maître d’ came to his viewing—it’s like a family.”

The namesake dish.

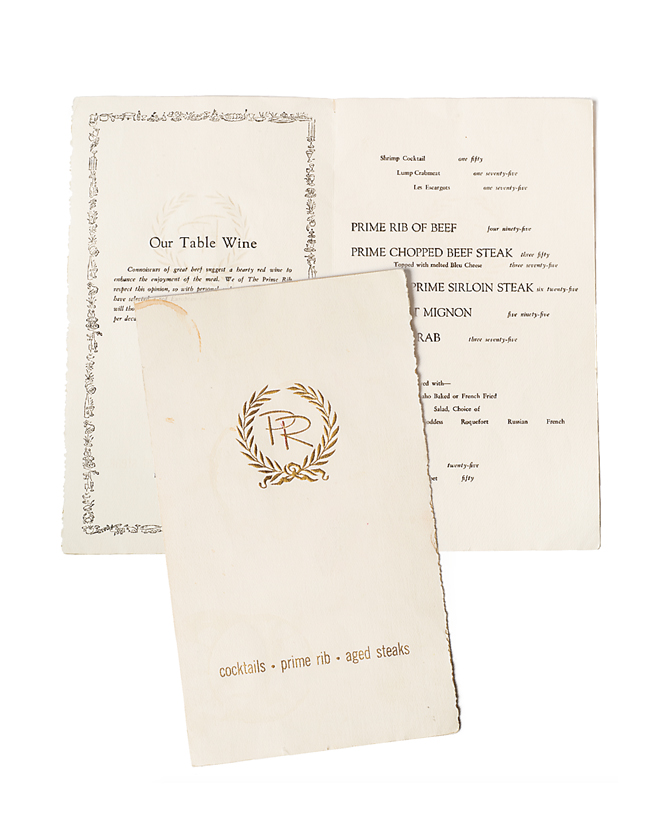

Like our presidents, our dogs (and much to our dismay, even ourselves), restaurants seem to age before our very eyes. What’s trendy today can become tired and stale tomorrow, which makes The Prime Rib’s enduring popularity that much more remarkable. Little has changed here since October 19, 1965, when guests first picked up their steak knives. In its infancy (and for much of its existence), men were required to wear jackets and ties, often smoked cigars, and the menu offered only a smattering of entrees. (The restaurant’s titular dish once went for $4.95.) Today, some diners wear khakis and golf shirts, and the kitchen serves nearly as much seafood as it does steak. Through the years, there have been cosmetic touch-ups, but, at its core, The Prime Rib remains the same swanky Baltimore steakhouse owners Buzz and Nick Beler created a half-century ago. The black lacquered walls with gold trim, the leopard-print carpet, and the piano in the dining room preserve the sense of sophistication that the restaurant has always exuded. As Esquire put it in a 2008 piece on the best steaks in America, “At the Prime Rib, it’s always 1965.”

Diners dig in.

The jazz and standards that play on the sound system or flow from the fingers of the pianist sitting at the Baldwin baby grand are the hits of yesteryear, but take a few moments and watch guests of all ages start to tap their toes to a Sinatra tune. Add to that an expertly made martini and a medium-rare, dry-aged USDA Prime New York strip served by a man whose sole purpose appears to be ensuring that your night out at his restaurant is beyond compare, and you’ll be compelled to agree that some things never get old.

Head Chef Jim Minarik readies the kitchen.

The entrance on Calvert Street.

The timeless décor.

Jackets in waiting.

Firing up the meat.

Waiter Aaron Day gets ready for dinner service.

Crafting libations at the bar.

Preparing the meat.

This spud’s for you.

Vintage menus with original pricing, including a prime rib of beef for $4.95.

Constantine Peter Beler —or is it BeLer?—was born in 1929. Or was it ’28? ’27? He’s not even sure himself. “Somewhere around there,” says The Prime Rib’s co-founder and owner from a corner table at the restaurant’s Washington, D.C., location, which opened on K Street in 1976. With its dark lighting, deep black leather tones, showy art on the walls, and yes, leopard-print carpet, it almost mirrors the original Baltimore location. “We used to spell it B-e-L-e-r, but that became kind of a pain in the ass. It’s a lot easier to write B-e-l-e-r, so we go by that.” Buzz, as virtually everyone has called him since he attended McDonogh School in his native Baltimore, is not just old, but unapologetically old-school. During a cocktail-hour conversation, Beler recounts his successes—and his failures—without bravado. While sipping a glass of Albariño, he curses often, but never without purpose. Spend five minutes with the man and it’s clear why his restaurants have managed to thrive virtually unchanged while the world around them has transformed. The son of restaurateurs, Beler and his only sibling, Nick, grew up in the North Inn, their parents’ 24-hour restaurant in Baltimore. After college—Beler attended the University of Virginia, then Maryland Law, while Nick earned a degree in genetics from The Johns Hopkins University and attended University of Baltimore Law School—each went his own way until the family trade lured them back to the business. “It was boring doing what we were doing,” Beler recounts. “Lawyers are a pain in the ass. I have a name for them: misery brokers. It brings you down.” On a lark, the brothers went to New York, hired a limo, and toured the city’s famous restaurants. They took notes, borrowing ideas liberally for their bistro, which they considered calling Buzz and Nick’s or Constantine and Nicholas’s. “We had a big debate about what the hell to name the restaurant,” Beler says. “I finally said, ‘Nick, if we’re gonna sell prime rib, why don’t we just call it The Prime Rib?’ He agreed. It was a good call.”

Seasoning the meat.

In the mid-1960s, the intersection of Chase and Calvert streets was part of a bustling downtown district, which is why Nick thought the ground floor of the Horizon House apartment building was the perfect spot for the restaurant. The younger brother also took the lead in the kitchen. After enjoying a particularly tasty steak in Chicago, he inquired about the restaurant’s supplier. When told it was a Windy City outfit, he placed an order. To this day, Chicago’s Allen Brothers trucks eight to 10 cases of prime rib to the Baltimore location each week.

For his part, Beler concentrated on the ambiance, working with local designer James Peterson on the décor and selecting art for the dining room. Many of the Louis Icart prints Beler purchased still hang on the walls today. When the steakhouse opened, success was immediate. “October marks the first anniversary of a restaurant I’ve found to be delightful,” food critic Gertrude Wilkinson wrote in a 1966 Baltimore review. “The food and drink are of the first rank, and the room is intimate, chic, sophisticated.”

Here’s a who’s who list of the well-knowns who’ve broken bread—or cut into steak—here.

Muhammad Ali

Maya Angelou

Rex Barney

Harry Belafonte

David Carradine

Tony Curtis

John Denver

Johnny Depp

Julius Erving

Bobby Flay

Joe Frazier

Zsa Zsa Gabor

Danny Glover

Lou Gossett Jr.

Peter Graves

Mark Harmon

Felix Hernandez

Bert Jones

James Earl Jones

Don King

King Abdullah II of Jordan

Ricki Lake

Ray Lewis

Liberace

Traci Lords

Heather Locklear

Bernie Mac

Kweisi Mfume

Lenny Moore

Jim Palmer

Rosa Parks

Maury Povich

Boog Powell

Ray Rice

Cal Ripken Jr.

Brooks Robinson

Pat Sajak

Arnold Schwarzenegger

Smothers Brothers

Bart Starr

Ichiro Suzuki

Kathleen Turner

Ted Turner

Desmond Tutu

Johnny Unitas

John Waters

Dr. Levi Watkins

Billy Dee Williams

Montel Williams

“Local people, particularly ones that were well-known and affluent, started coming,” Beler says. “And then we started getting people like Muhammad Ali. He could play the piano a bit. Liberace was a great guy. He would always come in after his shows. We’d keep it open until four o’clock in the morning for him, [although] he would never play the piano.” From Arnold Schwarzenegger to Zsa Zsa Gabor, a laundry list of luminaries spanning eras has dined at the Baltimore location. And even after the death of Beler’s baby brother and partner, Nick, who succumbed to cancer 20 years ago at the age of 63, The Prime Rib continued to thrive. The ensuing years brought more expansion—Beler opened a third Prime Rib in Philadelphia in 1997, and in 2012 he licensed the name to the Cordish Companies for a location in the Maryland Live Casino. While the dress code has loosened somewhat in Baltimore, where jackets are requested for men on Saturday nights, the D.C. location still requires a jacket during every dinner service and keeps 60 of all sizes on hand for those who need to borrow one. “The world’s changing,” says Beler, who most decidedly has not, as evidenced by his immaculately pressed black suit complete with a purple handkerchief in his breast pocket. “It’s not like it used to be. People were more intellectual. They enjoyed dressing up. Now they all dress like hobos.”

Like any successful businessman, Beler is, however grudgingly, amenable to change. But he won’t abandon his core principles. Thus, he’ll never fundamentally alter the look or feel of his dining rooms or lower the standards of service he demands from his waiters, whom he calls “friends.” Beler, who lives in the Watergate South in D.C. and spends most of his time in D.C., remains engaged in the business. “He’s still a driving force,” says Jim Minarik, the head chef in Baltimore. “He calls every day. He leaves us alone unless something’s not right, and then we hear from him.” Over the past two years, the Baltimore and D.C. locations closed briefly for renovations to the infrastructures of the buildings. “We got hundreds of [concerned]calls, ‘Are you changing that beautiful interior?’” Beler says. “We had to send an e-blast out saying it only related to the kitchen. We recognized, if you’ve got it, don’t [mess] with it.”

Like baseball players strolling into the clubhouse hours before first pitch, the all-male waitstaff wears their civvies as they trickle into the dark, empty restaurant well before it opens at 5 p.m. As they sit at the bar snacking and folding napkins, conversation ranges from politics to chicken farming to the Orioles. They trade war stories as, one by one, they disappear and reemerge wearing tuxedoes. Co-manager John Klaus recalls when a brawl broke out in the men’s room. The participants—“two old dudes who shouldn’t have been fighting”—crashed into the glass wall separating the dining rooms, shattering it. “They could have killed somebody,” says Klaus, an English major in college who came to work at the restaurant 30 years ago and never left. “We took $500 from each of them to pay for it.” From men with their mistresses to engagements to rejected marriage proposals—these guys have seen it all. But mayhem and bad behavior are rare exceptions, which partially explains why, in stark contrast to the rest of the industry, people who work at The Prime Rib tend to stay. (Another is this: On a busy night, servers can earn $400 in tips alone.)

Aaron Day’s first shift bussing tables was September 10, 1973. Seven years later, he was promoted to waiter, a position he still relishes today. “I’ve missed two days of work since I’ve been employed here,” says Day, 57. “One day, my father passed away, another I had to get my mother to the hospital.” Oprah Winfrey, Montel Williams, Maury Povich—the boldface names Day has served could fill the pages of People. When Rosa Parks came to dine, she would invite him to sit at her table. But Day treats all his guests like celebrities, providing The Prime Rib’s signature service—courteous and attentive, but not obtrusive.

“I [approach] every day like I’m fresh out of the blocks,” says Day, who even after 42 years, has no plans to retire. “As soon as the customer sits, within about 30 seconds we’re at the table. I use their body language to detect whether they want to [order] or relax. It’s a skill. We don’t change.” Minarik arrived shortly after Day. The head chef for 39 years, he gets in around 1 p.m. to begin prep work. Wearing a white apron with red stains and a Babe Ruth Birthplace Museum baseball hat, he directs a staff of about eight. “When I started, we had about six entrees,” he recalls. He seasons several whole prime ribs (each weighs 18 to 20 pounds) and feeds them into a custom Alto-Shaam oven for roasting. They’re ready after four hours, but in order to preserve their natural juices, aren’t sliced until someone orders one. On a typical Saturday, about a third of all entrees served are prime rib. “When you have the same chef for 40 years, when you have guys who have been here for 20 to 30 years, there’s a level of consistency that is important,” says co-manager Brad Black, a 13-year veteran. “Beler always says he can make a waiter out of anybody, but he can’t make a gentleman out of someone. Our guys are gentlemen. It’s hard to find these days.”

Dinner is served.

Around 7 p.m., Ernie and Donna DiPalo take seats at the bar, where their Beefeater martinis magically appear. A few minutes later, their 46-year-old daughter, Dina, shows up and is welcomed with a glass of Basil Hayden’s on the rocks. “We started coming here in ’66, and Dina has been coming to this restaurant since she was born,” says Ernie, who’s tieless, but “would not come in here without a jacket.” There’s nothing particularly significant about this evening for the DiPalos. They aren’t celebrating their 50th anniversary—that’s next year—or a landmark birthday. They’re just a couple of lovebirds sharing a nightly martini, then a lovely meal with their daughter at a treasured restaurant all of them have been dining at for more years than they haven’t. Come to think of it, this is a special night.

Here’s a who’s who list of the well-knowns who’ve broken bread—or cut into steak—here.

Muhammad Ali

Maya Angelou

Rex Barney

Harry Belafonte

David Carradine

Tony Curtis

John Denver

Johnny Depp

Julius Erving

Bobby Flay

Joe Frazier

Zsa Zsa Gabor

Danny Glover

Lou Gossett Jr.

Peter Graves

Mark Harmon

Felix Hernandez

Bert Jones

James Earl Jones

Don King

King Abdullah II of Jordan

Ricki Lake

Ray Lewis

Liberace

Traci Lords

Heather Locklear

Bernie Mac

Kweisi Mfume

Lenny Moore

Jim Palmer

Rosa Parks

Maury Povich

Boog Powell

Ray Rice

Cal Ripken Jr.

Brooks Robinson

Pat Sajak

Arnold Schwarzenegger

Smothers Brothers

Bart Starr

Ichiro Suzuki

Kathleen Turner

Ted Turner

Desmond Tutu

Johnny Unitas

John Waters

Dr. Levi Watkins

Billy Dee Williams

Montel Williams