Food & Drink

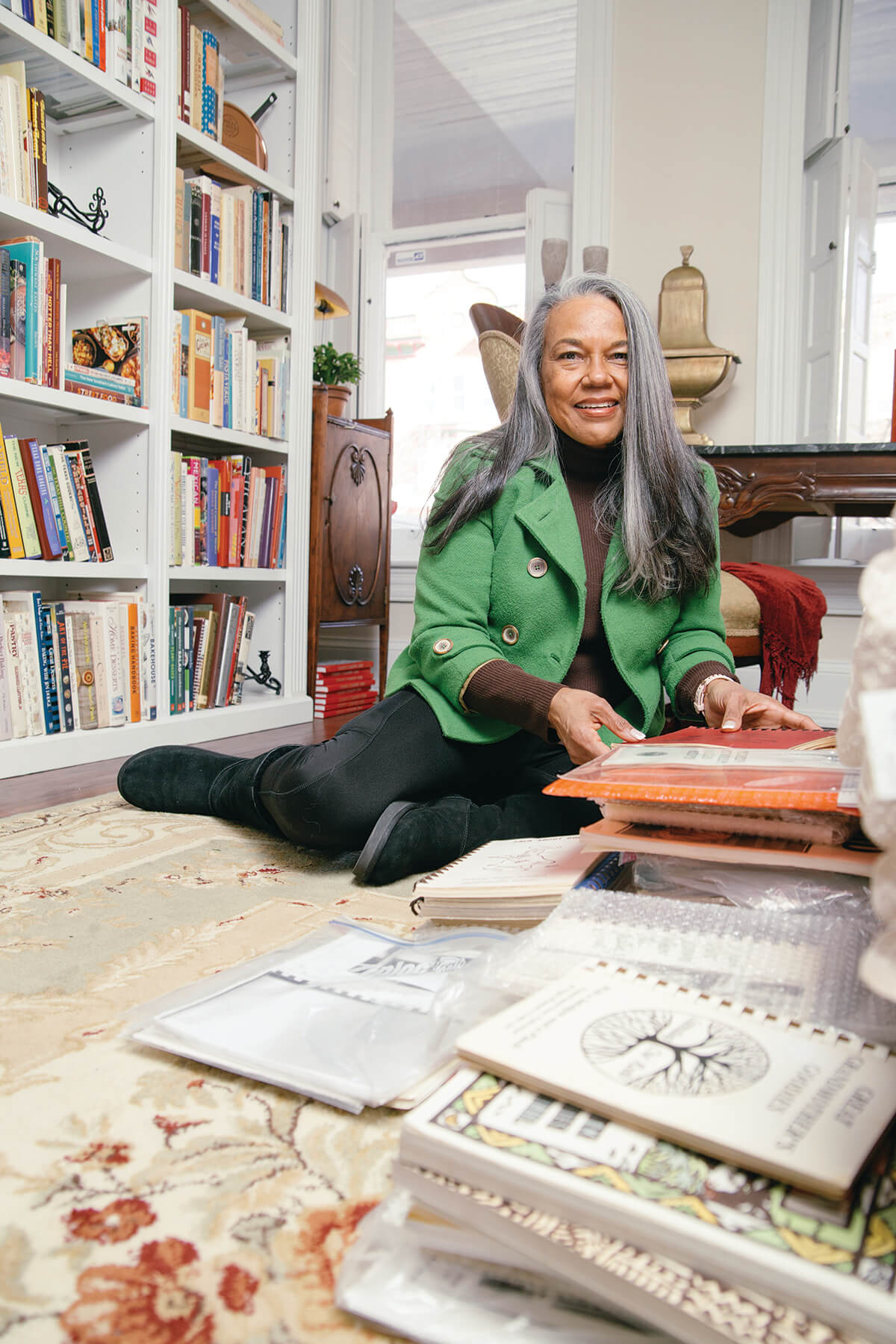

Legendary Food Writer Toni Tipton-Martin Makes Charles Village Her Home

The James Beard Award winner's road to Baltimore—and her life as a writer, archivist, historian, and broadcaster—was hardly a straightforward one.

James Beard Award-winner Toni Tipton-Martin never set out to amass more than 1,450 cookbooks, 450 of which were written by African Americans. It just happened.

“I never intended to be a collector,” she says. “But the African-American cookbook collecting began dominating my life when I started to hear stories that validated what I knew in my heart and soul but couldn’t prove: that African-American cooks had been knowledgeable and skilled. Those were stories that were not being reported.”

She found a veritable treasure trove of such books and recipes through her research and just kept going. She now stores many of those cookbooks in her recently purchased Charles Village home, a 120-year-old fixer-upper that she shares with her husband, Bruce Martin, a Naval Academy grad.

Her road to Baltimore—and her life as a writer, archivist, historian, and broadcaster—was hardly a straightforward one. She started out as a food writer in Los Angeles; accepted a job in Cleveland, becoming the first Black food editor of an American newspaper; took a two-decade hiatus to raise her four children; and spent 10 years researching a groundbreaking project.

And that doesn’t include the most recent highlight on her C.V., as a recipient of the annual Julia Child Award that came with a $50,000 grant she’s using to expand her current nonprofit to help aspiring food writers. Oh, and she’s also editor-in-chief of the folksy Cook’s Country magazine and hosts segments for its public television show as part of the America’s Test Kitchen franchise in her renovated parlor, or library as she calls it.

It’s safe to say that Tipton-Martin, 63, has managed to stretch a 24-hour day in awe-inspiring ways. “There’s an old saying that you can sleep when your time is up,” she shares during a Zoom call from her home office. “I’m really excited by the work.”

On this particular day, she was especially thrilled to find out Target was promoting her 2019 award-winning book, Jubilee: Recipes from Two Centuries of African American Cooking, for Black History Month. “I’m so proud my two-year-old book is worthy of inclusion,” she says.

Tipton-Martin also wrote The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks (2015), a revolutionary, James Beard Award-winning compendium that took a decade to research and write. But her interest in cookbooks started much earlier, when she was a food and nutrition writer for the Los Angeles Times in the ’80s and early ’90s, and continues to this day. The oldest book in her collection, The House Servant’s Directory, dates back to 1827.

As Tipton-Martin’s African-American collection grew, she realized the books could be organized into chronological sections and social themes—from the early 19th century through 2011—which led to The Jemima Code. She included original recipes, menus, and household tips along with her critiques of the various books, but The Jemima Code is more a reference book than a cooking guide.

Her goal, as she set out to prove there was know-how behind the jolly Aunt Jemima caricature, was to show that the African-American authors understood the constructs of cooking and home management and weren’t just relying on natural instinct.

When she finished writing The Jemima Code, Tipton-Martin wanted to continue honoring the little-known authors and began translating their recipes for today’s kitchens in her book Jubilee. To decide which recipes to include, she cooked several versions of a dish, settling on one that would work for a modern cook. Sometimes, she would adapt or create a new recipe, based on the original. The result was a collection of comfort-food recipes, including main dishes like barbecued pork shoulder, buttermilk fried chicken, and shrimp Creole.

Tipton-Martin doesn’t know the exact number of cookbooks she has. A dozen boxes of books are still unpacked in her basement. But she keeps the modern-day cookbooks on shelves in the library and in her office. The rare editions are stored in a climate-controlled facility. As she talks about her books and accomplishments, it’s evening now, and she’s winding down from her busy schedule, settling into a desk chair, wearing a blue-gray, crewneck pullover and thick-rimmed glasses, her silver-streaked mane pulled into a long ponytail. She has a calm, thoughtful demeanor.

“I can’t imagine how she’s juggling all of it,” says Nathalie Dupree, a Southern doyenne, chef, and award-winning cookbook author based in Raleigh, North Carolina. “She has so many people reporting to her now.”

Dupree, who was a speaker during Tipton-Martin’s virtual Julia Child Award presentation in November in Washington, D.C., praises the journalist for her contributions. “She really was the forerunner of so much of the writing about African Americans and about doing research on their contribution to the food world,” says Dupree during a phone conversation. “And I can’t say it enough, she was the only Black woman in the industry of food editors for a long time.”

Tipton-Martin considers Dupree a mentor. She credits her with helping her understand the synergy between Black and white women in American kitchens. “The story isn’t as one-sided or as mean-spirited as it is often portrayed,” she says.

She also subscribes to Dupree’s pork-chop theory, which uses a cooking method as an analogy for people, mostly women, supporting each other. Dupree and food scientist Shirley O. Corriher developed the premise when both were carving out careers in Atlanta in the mid-1970s. Dupree explains, “If you have one pork chop in the pan, it goes dry. If you have two pork chops in the pan, the fat from one feeds the other. If you face the fact there is going to be room in the pan, you make room in the pan. All the women I have mentored understand this.”

“…SHE WAS THE ONLY BLACK WOMAN IN THE INDUSTRY OF FOOD EDITORS FOR A LONG TIME.”

Tipton-Martin and Dupree met at the Southern Foodways Alliance, an organization focused on the food cultures of the South, while Tipton-Martin was the group’s acting president and Dupree was on the board. “I’m one of her mothers,” Dupree says with a laugh. “She wasn’t from the South, and we would talk about the South a lot.”

Tipton-Martin’s work at the Alliance helped her to re-enter corporate America after taking off 22 years to care for her family, though she kept a hand in the business as a freelance writer and editor, mostly to pay for the books she was seeking. The first obscure tome she acquired was Eliza’s Cook Book (1936), which she purchased in an online bidding war for $400.

Her children are grown now—Brandon, 40; Jade, 39; Christian, 29; and Austin, 25. They are scattered around the country, but she works closely with Brandon, a graphic designer, who is partnering with her on her next venture, an African-American cocktail book.

There’s no pub date yet for the book or for a memoir she’s penning. “I write a couple of sentences of each one every day,” she says. Tipton-Martin says she’s gotten bogged down with contractor issues at her five-bedroom, 2 1⁄2-bath rowhome, which is one of the colorful 19th-century “painted ladies” in North Baltimore.

The house had been abandoned when she and her husband bought it at auction, but they were seduced by its original character and details like pocket doors, transom windows, a back staircase, servants bells, and retrofitted gas lights. “We’re historic preservationists,” she says. “We salvaged everything we could.” She’s also become a regular shopper at Second Chance, the South Baltimore salvage warehouse. “If I need something, it’s the first place I go,” she says.

While the couple bought the house in 2018, Tipton-Martin didn’t move in permanently until last year due to contractor issues. Her husband’s job in sales brought them to the area. “We could have lived anywhere in the region,” she says. “We settled in Baltimore by choice.”

One of the favorite parts of her neighborhood is the 32nd Street Farmers Market in Waverly. “It’s carnival-like, people having such a good time together, gathering, and reuniting,” she says. “It’s more than a place you go shopping for food. It’s a marvelous example of the potential of the city. I really like that.”

Her wanderings have also taken her to Soldiers Delight Natural Environment Area in Baltimore County, where she and her husband like to hike; La Cuchara restaurant in Woodberry; Whitehall Market in Hampden; and, to satisfy her “taco-junkie” cravings, Tortilleria Sinaloa in Fells Point.

Along the way, Tipton-Martin and her husband became fans of David and Tonya Thomas, first at Ida B’s Table, the soul-food restaurant they operated in Baltimore, and now at their event space and catering business, H3irloom Food Group. When the Thomases invited Tipton-Martin to a Valentine’s Day dinner, she didn’t hesitate, even though she was working on deadline.

“I turned off the computer, grabbed my boo, and went,” Tipton-Martin wrote on Facebook. “Great ambiance, delicious food, and special friends.”

The Thomases, who also are exploring African-American foodways, cherish the friendship. “Toni Tipton-Martin is one of the greatest food writers and archivists of our time,” says David Thomas. “She is considered one of the pioneers in the food world,” adds Tonya Thomas.

The couple look forward to what Tipton-Martin will contribute to the city’s food scene. “Toni will bring credibility and legacy to Baltimore,” David Thomas predicts. “It’s really having this firebrand, this legend, who descends on Baltimore and understands the work that needs to be done.”

As a teenager, Tipton-Martin, who grew up in Southern California, briefly thought about living abroad to take advantage of her fluent French, but instead decided to major in journalism at the University of Southern California, graduating in 1981. She worked part-time at a community paper, The Wave Newspapers, where she was assigned to the recipe section.

“I started watching more food television, which is how I became enchanted with Julia [Child],” she says. “Julia was talking about doing stories on food that were close to her heart.”

Tipton-Martin began to see how personal food could be, how wrapped up it was in identity and culture. She landed at the Los Angeles Times in 1983 as a nutrition writer. But it wasn’t until Ruth Reichl became food editor in 1990 that she was able to stretch her skills as a writer.

“I saw some of her copy, and I went to her and said, ‘Do you really want to be writing about nutrition? You’re too good,’” says Reichl, a former restaurant critic for The New York Times and editor of Gourmet magazine, who now writes a newsletter, La Briffe, for the online platform Substack. “We finally had some diversity [at the Los Angeles Times]. It was such an opportunity to be able to be covering food, not from a middle-class, white perspective, but from a much larger perspective.”

Tipton-Martin remembers the nudge well. “When Ruth came on, she was so generous of spirit and encouragement, and essentially asked me what I wanted to do with my work,” she says. “I said I didn’t know. She said, ‘Go out to the streets of L.A. and don’t come back until you know.’”

After three days, Tipton-Martin came back with story ideas, specifically ones that did not contain recipes, a watershed moment for the Los Angeles Times. Reichl wasn’t surprised. “I had this great resource in this really bright, really good writer who was very ambitious to do other things,” she says. “And for an editor, what more can you ask?”

“TIPTON-MARTIN BEGAN TO SEE HOW PERSONAL FOOD COULD BE, HOW WRAPPED UP IT WAS IN CULTURE.”

Opportunity soon came knocking for Tipton-Martin in the form of a food editor position at The Plain Dealer in Cleveland. “I was very proud of her,” Reichl says. “I thought it was sad for us. But I always wanted my people to go on and do bigger things.”

After five years at The Plain Dealer, Tipton-Martin left the industry until her youngest child graduated from high school. When she returned to the workforce, she knew her calling was in a different type of food journalism, though she’s thankful for her experience. “If it hadn’t been for my journalism skills, The Jemima Code wouldn’t exist, and those stories wouldn’t have been told,” she says. “It was very much like putting together an investigative piece.”

She realized that the information she sought about African-American cooks could be found in cookbooks, where she could glean their cooking techniques and also gain insight into their lives. “At the Southern Foodways Alliance, I encountered more and more scholars who were exploring that work,” she says. “It piqued my interest and caused me to start looking for sources of my own.”

Tipton-Martin turned to scholarly works like Eat My Words: Reading Women’s Lives through the Cookbooks They Wrote (2002) by Janet Theophano and Black Hunger: Soul Food and America (1999) by Doris Witt, and took a seminar at Radcliffe College about the methodology of interpreting a cookbook author’s words and meanings. By the time The Jemima Code went to the publisher, she had compiled 160 essays about Black cookbooks.

Perhaps there has been no bigger impact on her career path than the death of her father, Charles Hamilton, who was 56 at the time, in 1995. He died from injuries sustained in a car accident. “My dad was, I use the word murdered because I mean that, killed in Los Angeles in a hospital by an unsupervised intern,” she says. “His life was disregarded by the hospital. It became important to me to find a way to speak on behalf of the voiceless.”

She formed a nonprofit, the SANDE Youth Project, to fulfill her vision of improving community health. “Pain and grief gave me purpose,” she says. “A good reporter, someone delivering good news, can bring healing to a community.”

Southern writer Dupree has watched her mentee become a mentor over the 20 years she has known her. “I don’t think a lot of the young women who have moved into prominence would be there if Toni hadn’t been paving the way,” she says. “She made it look easy.”

Jamila Robinson, who became food editor of The Philadelphia Inquirer in 2020, credits Tipton-Martin with having an impact on a career that has led her to become a Black leader in a newsroom. She also sees Tipton-Martin’s trailblazing path as encouraging for the future.

“I find that to be inspiring because we can find opportunities to make sure that other Black journalists see food as a pathway in journalism,” say Robinson, who is also the committee chair of the James Beard Foundation Journalism Awards. “Toni Tipton-Martin created a pathway for others to stand on. I stand on her shoulders.”