Food & Drink

How Tulkoff Food Built a Horseradish Empire in Baltimore

Strong, spicy, pungent—and known to clear a sinus or two—Tulkoff's fiery products have local roots that date back 98 years.

With its refrigerated trucks and vast parking lot, the outside of the Tulkoff Food Products plant looks like every other business in the industrial park. But the 98-year-old business is anything but ordinary.

The six-acre site Tulkoff occupies in Holabird was once part of an active Army base during World War II—it’s where they tested the iconic Willys Jeep—and now houses a football-field-sized room filled floor to ceiling and front to back with horseradish.

You might think that a room filled with over two million pounds of horseradish root would make your eyes water, or at least your nose tingle, but instead it smells like the dirt that still clings to the root of the horseradish plants from when they were two feet in the ground. (Horseradish’s signature nasal-clearing kick comes from oils called isothiocyanates that are released once the roots are crushed.) And standing in Tulkoff’s lobby—filled with mementos from nearly a century of business—the strongest scent seems to be fresh ginger wafting from another part of the factory floor.

Phil Tulkoff, the company’s president for the past 19 years, descends the staircase. He’s warm but not overly chatty. There’s not an extra second in his day to spare. Were it not for the speckles of gray in his beard and some laugh lines around his eyes that get activated when he talks about his family, you’d never guess he was in his 60s. A sweet golden retriever named Sofie—Tulkoff is fostering her for the Valor Service Dogs program—trails after him.

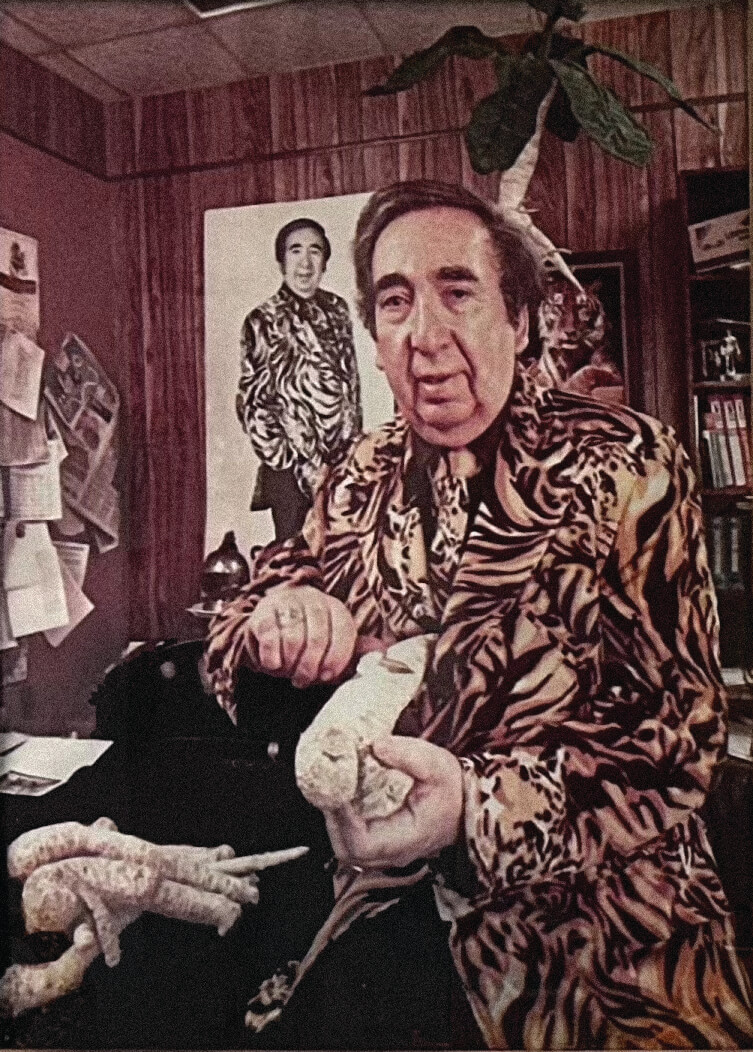

As he walks back up the stairs to his office, he passes a sepia-toned photograph of his Uncle Sol, clad in a tiger-patterned sports coat, peeling horseradish root. Look closer and you’ll see that Sol is standing in front of another black-and-white photograph of himself in the exact same coat.

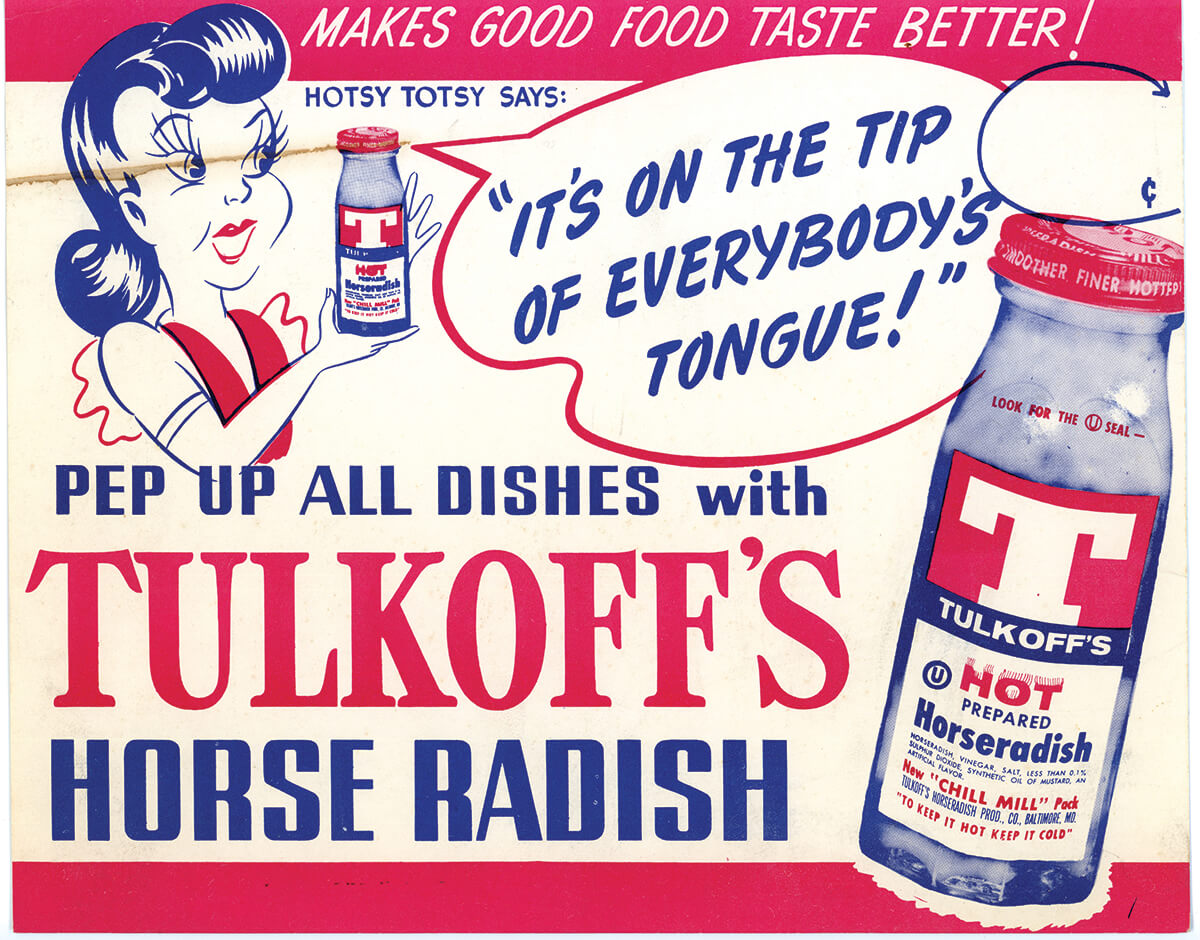

(That tiger pattern is no mere fashion statement. Upon returning home from Europe after WWII, Sol was determined to incorporate the war symbol of a tiger crushing a German tank into the Tulkoff product line and, with that, Tiger Sauce was born.)

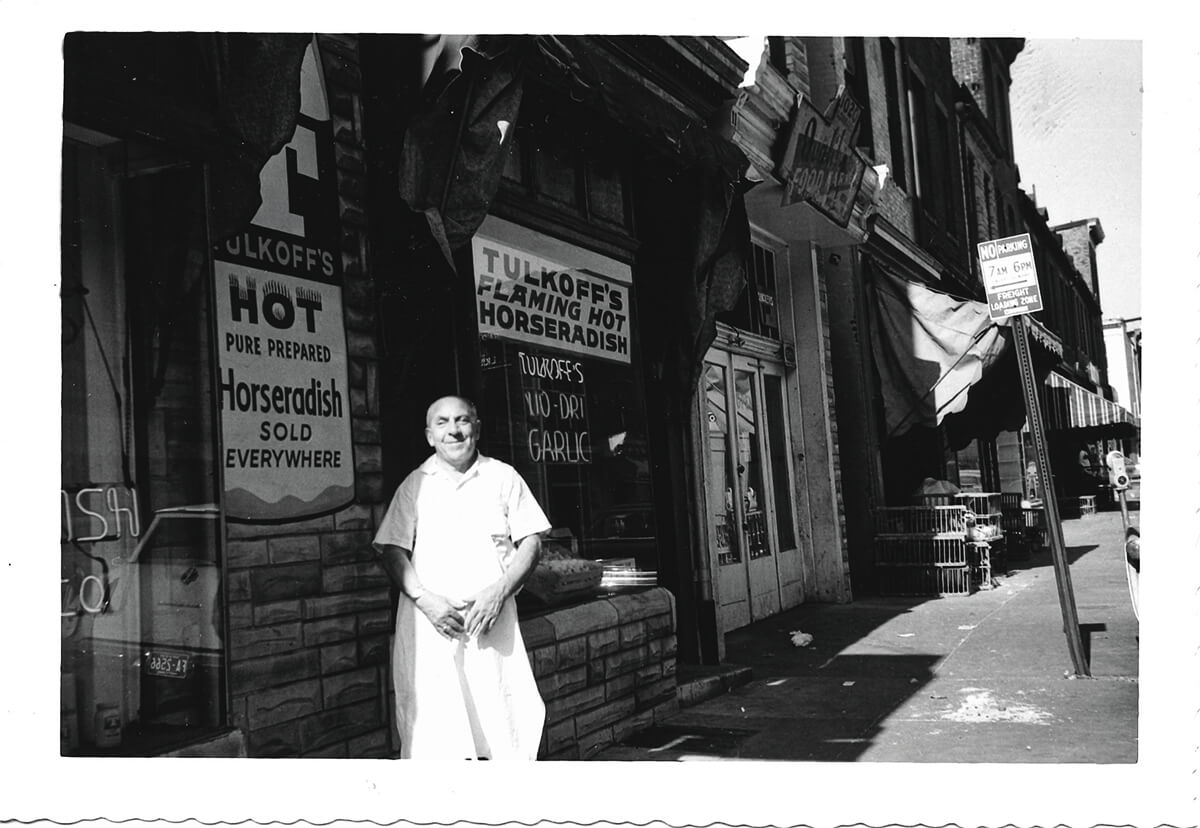

Tulkoff settles into a chair behind his desk. The room is part museum—there’s a big photograph on the wall of the company’s previous headquarters in Brewers Hill (before luxury condos and Target) and some of their original packaging with retro logos of times past—and part central command.

Tulkoff, the third-generation owner of this venerable Baltimore business, doesn’t have a window to the outside world, but instead a bird’s-eye view of his world: the state-of-the-art facility where workers wearing blue factory coats and hairnets sort, package, and fill products.

“I SORT OF HAD TO LEARN THE FAMILY BUSINESS AND FIGURE OUT WHAT WAS GOING ON.”

It took Tulkoff over 22 years to join the family business. He was busy being an aerospace engineer, including for NASA, where he designed and tested thermal control systems for free-flying satellites and space shuttle payloads. But in 2004 he got a call from his father, Marty Tulkoff, who asked if he and a board member could take him to dinner.

“And that was my mistake,” deadpans Tulkoff. “I said yes.”

He never thought he’d be a part of the family-owned company, but he couldn’t deny the timing felt serendipitous—he was ready for a change.

“This opportunity kind of made sense, but I didn’t really know what I was getting into,” he admits. “I had not been involved at all for many, many years. So, I sort of had to learn the family business and figure out what was going on.”

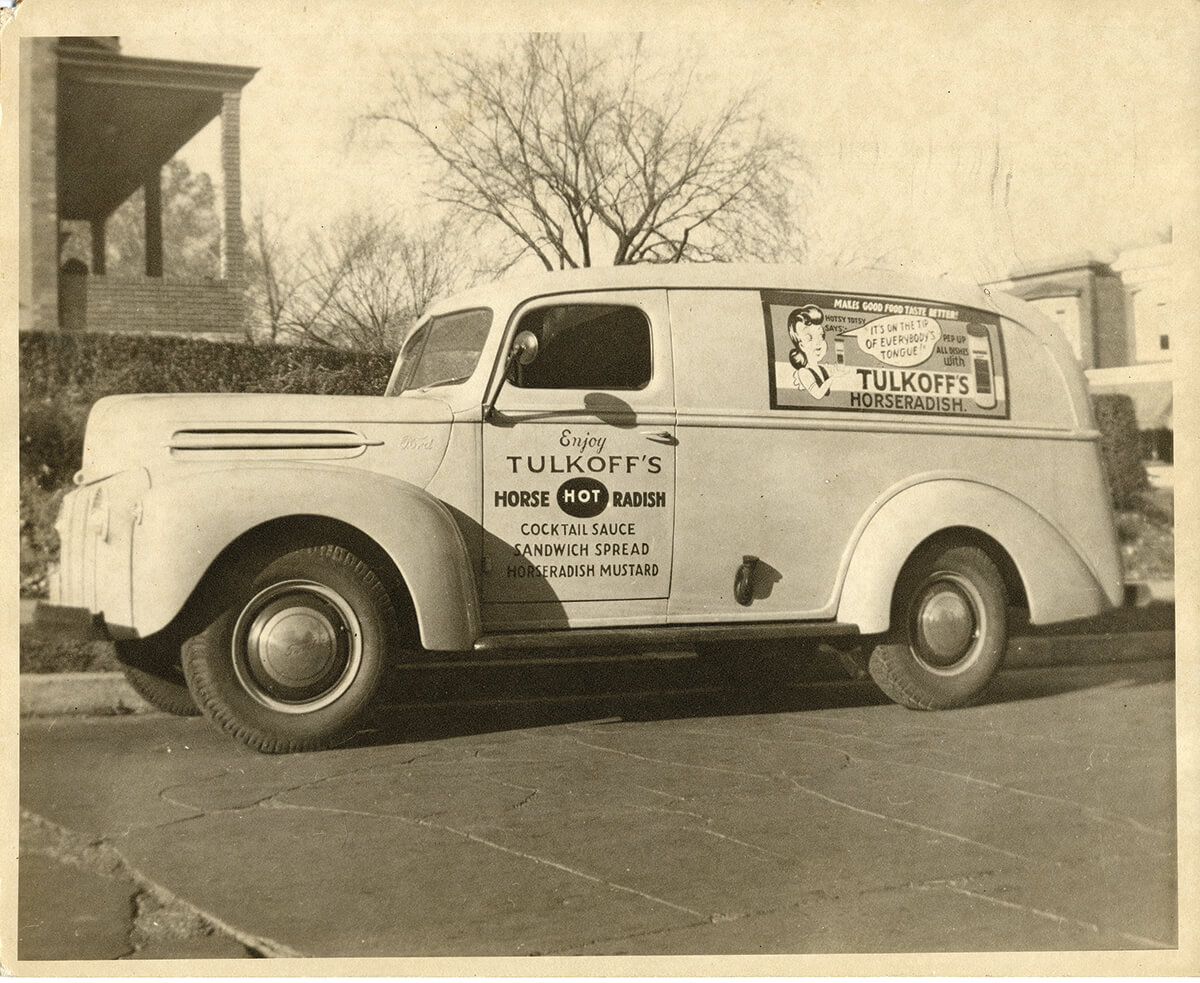

The business was horseradish. Although today, a lot of the company’s revenue comes from manufacturing, packaging, and labeling products for other condiment companies, back in the day, it was all horseradish all the time. Starting in a small shop run by Harry and Lena Tulkoff, it grew it into a company that, at its height, claimed 75 percent of the market share for horseradish products in the United States.

Unlike other horseradish companies that focused on sitting on individual grocery store shelves, Tulkoff concentrated on wholesalers and restaurant chains. Which means you’re less likely to see them in the condiment aisle at Graul’s or Eddie’s, and more likely to see them spicing up a Bloody Mary at your cousin’s California wedding.

Like his predecessors, Phil Tulkoff has found ways to keep the business afloat, even if it occasionally means upsetting some customers. (For the first time ever this year, they didn’t produce horseradish that was Kosher for Passover.) But survival is something his family, starting with his immigrant grandparents, knows more than a little something about.

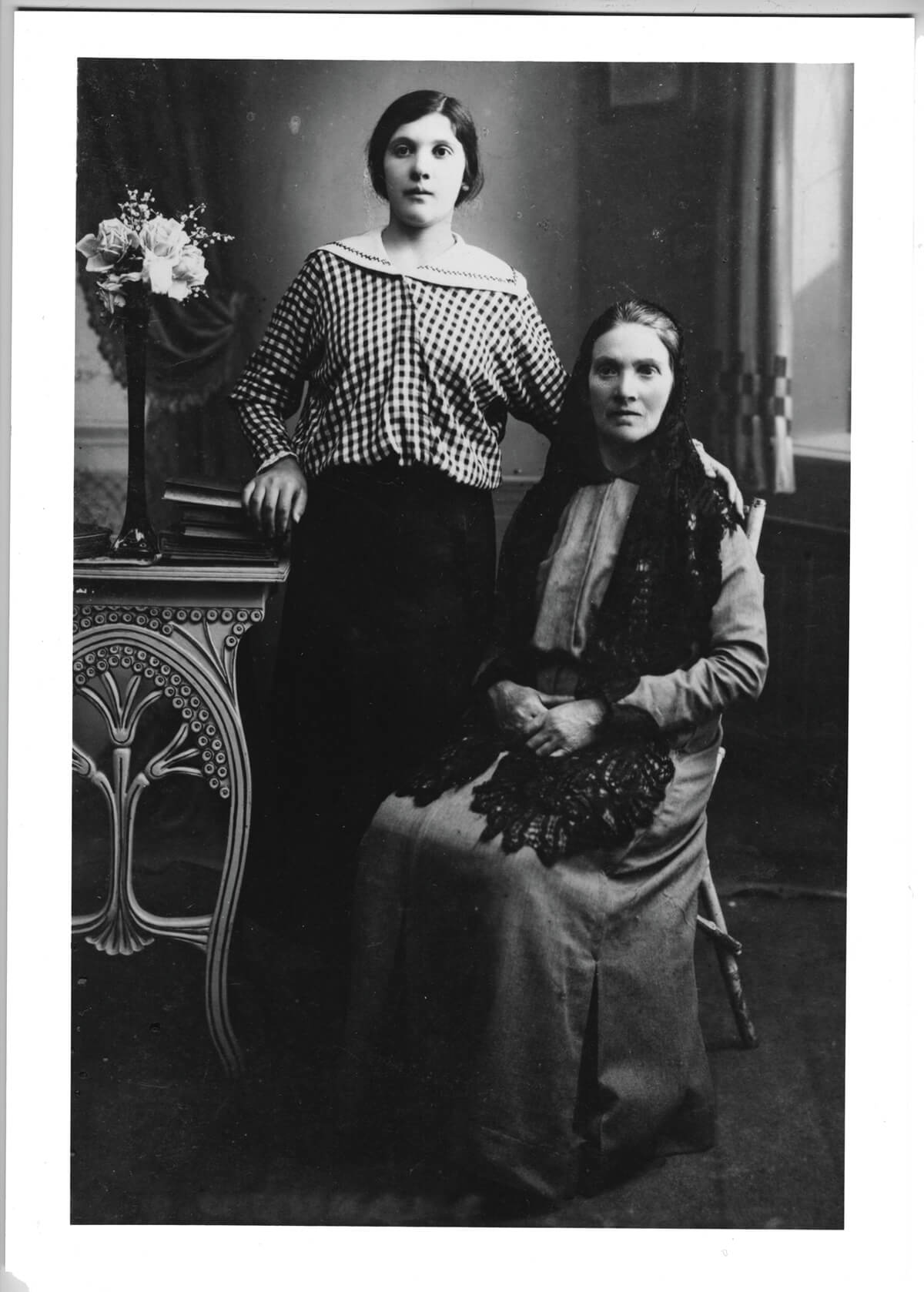

In 1917, Lena Pollock and her mother, Hannah, boarded the Trans-Siberian Railroad to start a 15,000-mile voyage toward a better life, eventually landing in Montreal. A year later, Lena moved to New York City and met Harry, who had emigrated to the United States as a teenager from Russia. The two married on Oct. 9, 1920, and together owned a dairy store in the Bronx they were able to quickly sell for an “alleged five-fold profit.”

At the same time, a family member from Baltimore asked for a loan but never paid it back. And, as the story goes, after repeated calls and attempts at contacting the borrower, Harry traveled to find them in person. Baltimore was like Manhattan, with its storefronts and bustling streets, but it also felt less competitive and more livable. It felt like home. And so, on that same trip, Harry found a storefront he could rent for $75 a month and secured 1103 East Lombard Street on Corned Beef Row. His family soon followed.

It took a while to find their footing. They operated several businesses out of the Lombard Street locale, including wholesale ice cream from the Jersey Ice Cream Company, with Harry claiming to have employed “as many as 200 people selling ice cream from carts fanned out all over Baltimore City.”

Over 10 years, they expanded their company—concentrating on produce, moving to a larger-scale manufacturing facility one block away at 1014 East Lombard—and their family. (The four Tulkoff children, Solomon, Essie, Bernice, and Martin, were all born between 1921 and 1934.)

There they reestablished themselves as The New York Fruit Company, specializing in supplying caterers with fresh fruits and vegetables.

There are many versions of how Harry and Lena ended up in the horseradish business. Sol would tell the story that, in the mid-to-late 1930s, a man entered the store and asked Harry if he was interested in a heap of horseradish root that someone had decided not to purchase.

Ever the entrepreneur, Harry went to look at the roots, which were sitting in a rail car at the end of Central Avenue. He purchased the whole lot, according to family lore, and grabbed some hay from a local stable.

Then he “methodically layered hay and roots in their backyard, keeping the roots fresh until they were needed.”

He had no idea that he was literally laying the foundation of a family business.

When Harry first acquired that haul, horseradish was mostly being prepared at home. Roots were ground by hand, then mixed with salt, vinegar, and water. However, the idea that it could be prepared elsewhere was catching on, as other family horseradish business were emerging in heavily populated Jewish areas, including Kelchner’s in Pennsylvania (established in 1938) and the popular Gold’s, founded in 1932 by Tillie and Hyman Gold in their Brooklyn kitchen.

(“I’m actually good friends with Steve Gold,” says Phil Tulkoff, referring to Tillie and Hyman’s grandson, who was a third-generation horseradish proprietor before selling the company in 2015. “He literally texted me a month ago and wished me a Happy Passover.”)

“BALTIMORE HAD A READY HORSERADISH MARKET WITH THE EASTERN EUROPEAN AND JEWISH POPULATION, OFTEN ONE AND THE SAME.”

In 1907 there were 40,000 Jews living in Baltimore, according to the Jewish Museum of Maryland. By the ’20s that number had swelled to 65,000, and due to the turbulence in Germany, another 3,000 Jewish refugees settled in Baltimore between 1933 and 1941.

And they loved horseradish.

“These products were a huge time-saver for people—women, servants, even restaurants,” says Kara Mae Harris, author of Festive Maryland Recipes, a holiday recipe and history book, and the Old Line Plate blog. “Baltimore had a ready horseradish market with the Eastern European and Jewish population, often one and the same,” she says.

As his business grew, Harry invested in motorized equipment, which is now on display in the Baltimore Museum of Industry’s “Food Processing” gallery. (He was also awarded proclamations from Baltimore Mayor Theodore R. McKeldin and Gov. J. Millard Tawes, declaring the week of Nov. 1-8, 1966, to be Horseradish Week.)

“This fiery condiment offers more pre-possessing foods a gentle kick in the pants. The perfect answer to the mildness of gefilte fish, chrain—as it’s also called—comes in a more bitter, white version as well as in a sweeter ruby-red one,” wrote Daphne Merkin in Tablet magazine’s “100 Most Jewish Foods.” (“This is not a list of good food,” the feature starts. “The point, instead, was to think about which foods contain the deepest Jewish significance—the ones that, through the history of our people—however you date it—have been most profoundly inspired by the rhythms of the Jewish calendar and the contingencies of the Jewish experience.”)

It is sometimes used as an ingredient in cocktail sauce, but its real claim to fame is the heat it brings to Jewish delicacies, her ode continues. “Let the WASPs have their Worcestershire; leave it to the Jews to turn suffering into a craving. For those who are charmed by this condiment, as I am, it is possibly most gratifying eaten on its own, directly out of the jar.”

Horseradish is the funny sounding, hardy perennial plant of the family Brassicaceae (which also includes mustard, wasabi, cabbage, and radish). Legend has it the Delphic oracle told Apollo, “The radish is worth its weight in lead, the beet its weight in silver, the horseradish its weight in gold.” According to the Horseradish Information Council, Egyptians used horseradish as far back as 1500 B.C. The Greeks used it as a rub for lower back pain and an aphrodisiac.

But why horseradish? In German, it’s called “meerrettich” (sea radish) because it grows by the sea. Many believe the English mispronounced the word meer and began calling it mareradish. And that eventually morphed into horseradish. Now the root vegetable is cultivated and used worldwide as a spice and condiment, popular on both ends of the spectrum: from oyster platters to Passover Seder plates.

It has a strong, spicy, and pungent flavor—like an American version of wasabi. It adds kick and punch and has been known to clear a sinus or two. It does well when added to something banal—like a roast beef sandwich or sweet charoset. It’s like hitting the gas pedal on your palate.

“It adds a really unique and spicy flavor that disproves the idea that people in the past ate primarily bland foods,” says Harris.

She recently made a historic sauce from the 1800s that has green tomatoes, onions, and horseradish in it, seasoned with cinnamon and cloves. “I don’t go out to a lot of restaurants, but I don’t think I really find a lot of horseradish being used creatively except for wasabi. Instead, the need for horseradish is kept alive in tiger sauce or as something we have to have with shrimp cocktail, oysters, or a pit beef sandwich. There are certain situations where we expect that flavor.”

All Tulkoff Food Products’ horseradish now comes from Collinsville, IL, just east of St. Louis. The harvest is generally from November to June. “But we have to store enough to get us through the rest of the year, because we grind horseradish almost every day,” says Tulkoff.

It’s a very labor-intensive crop, there are no seeds, and you have to cut a piece of the root, save it for the next planting season, and put it in the ground. And there are only about five or six farmers left in the country who are doing that. One of Tulkoff’s biggest horseradish purveyors was out of Canada, but they recently sold the farm and stopped producing the root.

“That hurt because I had to make up a million pounds,” he says.

“THE NEED FOR HORSERADISH IS KEPT ALIVE AS SOMETHING WE HAVE TO HAVE WITH SHRIMP COCKTAIL, OYSTERS, OR A PIT BEEF SANDWICH.”

The horseradish storage room at Tulkoff casts a blue aura, thanks to the cube-like horseradish bales stretch-wrapped in blue plastic casing to keep them bound. Tulkoff is fond of pointing out that what you see—though impressive—is only the surface.

“Notice that we’re four deep and six high. So, when you look across to that other wall, you’re just seeing one of the four bales that goes all the way back to the wall.”

And it’s 1,200 pounds for each one.

The room is kept at an exact 28 degrees. “Kind of an odd duck temperature, right?” says Tulkoff playfully. He explains: If you want something frozen, you’d set the temperature somewhere between zero to minus 10; if you want it refrigerated, it would be around 38 degrees. But if horseradish is frozen, you’d damage the root, and if it’s refrigerated, it’s such a hardy root it’ll try to start to grow.

“So, way before me, somebody figured out that 28 is that optimum temperature,” says Tulkoff. It’s the universal horseradish temperature. Not too hot and not too cold.

At that perfect temperature, horseradish root will keep for a long time. “Believe it or not, climate change is hurting us in a way I never would have thought,” says Tulkoff. “This suddenly started about three years ago; the farms would either get snow or it would turn really cold during parts of the year, which meant that they couldn’t harvest.”

That’s when Tulkoff would work through his inventory. Now the weather has been so perfect, they never stop. It’s feast or famine.

“So, I never get a break. And therefore, I’m like, half a million to a million pounds overstocked because it just keeps coming. It’s killing my storage capabilities.”

Next door to the storage room is the washing and grinding room. “We won’t let people take pictures of this,” says Tulkoff of the specialized washer. “It’s one-of-a-kind that we designed and had built for us.”

The staff can load three to four of the horseradish bales into it and it rotates and bounces around with just water and friction (no soap, no solvent) to clean the horseradish. After 40 minutes, they reverse the cycle and it comes back out onto a conveyer.

Before it gets ground, it passes through a little tunnel that acts as a metal detector.

“This is coming from a farmer’s field, so we find shotgun shells, tools, knives, pieces of equipment, you name it,” says Tulkoff. “We’re trying to protect the equipment, so we don’t put metal through the grinder.”

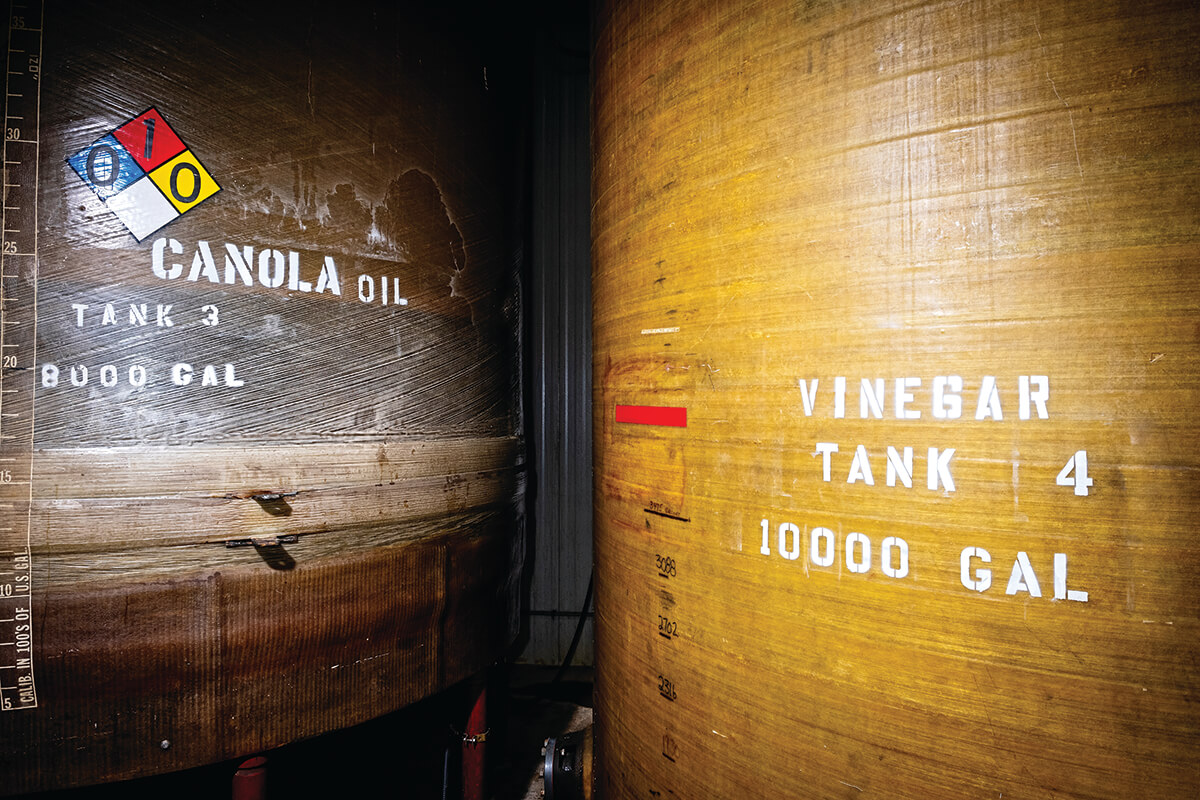

That ruins not just the machine but obviously spoils the batch as well. After getting ground it travels to a ribbon blender, which automatically adds the other ingredients—including water and distilled vinegar—and then it goes into one of three holding tanks, each one capable of holding 2,000 gallons of horseradish.

Oh, and Tulkoff answers the age-old question: Yes, red and white horseradish are exactly the same, except for some concentrated beet juice to make one version red.

“I think the red could technically be a little bit weaker because it has an ingredient that doesn’t have heat to it,” says Tulkoff. “But it’s not.” (See, mom!) There’s also folklore that in a Jewish neighborhood when someone asks if you prefer red or white—they don’t mean the wine.

After the storage and the washing and the blending of the horseradish, it’s a choose-your-own-adventure on what Tulkoff refers to as the “wet side” of the factory. From the tanks, the horseradish gets pumped to whichever production line it’s needed for.

Sometimes that means being bottled simply as horseradish, or other times it’s an ingredient added to another product like cocktail sauce, or their popular Tiger Sauce, now called “creamy horseradish sauce.”

“One of the coolest things about Baltimore’s food culture is the way that it reflects the city’s history of international roots,” says Kit Pollard, co-author of The Lost Restaurants of Baltimore. “You see it on menus in dishes like sour beef and dumplings, which celebrates the German community, and in communities like Greektown, where old-school Greek restaurants coexist with Latin American spots, telling a story about shifting demographics in the neighborhood.

“The same is true of Baltimore’s longstanding food companies,” she says. “The Tulkoff story starts in Russia and makes its way to Baltimore, where those Russian roots became part of the city’s food story thanks to bottles of horseradish. And in kitchens around town, Tulkoff is sharing counter and fridge space with other old-school Baltimore brands that rep their global heritage: Pompeian Olive Oil, Sun of Italy seasonings and sauces, Binkert’s sausages.”

Even Old Bay, she reminds us, “which is quintessentially Baltimore, is the creation of a German immigrant.” (Spice maker Gustav Brunn and his family were among the post-Kristallnacht refugees to arrive in Baltimore in 1938.)

It’s a legacy Tulkoff knows well, and while he tries not to dwell on it, it’s hard not to when your name is literally on the door.

“You don’t want to do anything that embarrasses you or the family or the business,” he says. “Being able to get it to the next level has been very rewarding. We’re almost five times bigger than when I started.”

He knows his grandparents would be proud—even prickly Harry. “He was not your lovable softy grandfather. He was pretty much the opposite,” says Tulkoff.

He remembers calling his grandfather to tell him he was heading to Bucknell University to study mechanical engineering. “His first response was, ‘What the hell do you want to do that for? I built a business for you. Never forget that.’”

All these years later, Grandpa Harry was right.