Baltimore-based tech company Catalyte shows how investing in people works for everyone in the long run.

By Corey McLaughlin

Photography by Erin Douglas

Tim Reed didn’t believe it. He had just dropped out of college at Morgan State after five years, in part because he couldn’t afford to pay tuition anymore, when he saw an online job advertisement that looked fake.

“You’re going to train me for free, then set me up with a job?” he says, recalling his first impression when he saw a vague Craigslist ad from a software development company in Baltimore called Catalyte. “I thought it was a scam.”

The promise might have sounded too good to be true, but it wasn’t. Roughly six years later, Reed—a City College graduate—is now a quality-assurance manager at the relatively little-known but far-reaching downtown-based company that did everything it promised.

After he finished a two-hour online screening—only about 15 percent pass—Reed (who had previously been pursuing an electrical engineering degree) was trained by Catalyte managers in software development for six months at no cost.

After that, the company offered the 30-year-old a full-time job, an opportunity that on average pays employees close to $100,000 a year within five years of them completing Catalyte’s signature training program. That’s an annual salary higher than 80 percent of Americans and five times greater than what the average Baltimore City public high-school graduate with a four-year college degree is earning six years out of school, according to Catalyte CEO Jacob Hsu.

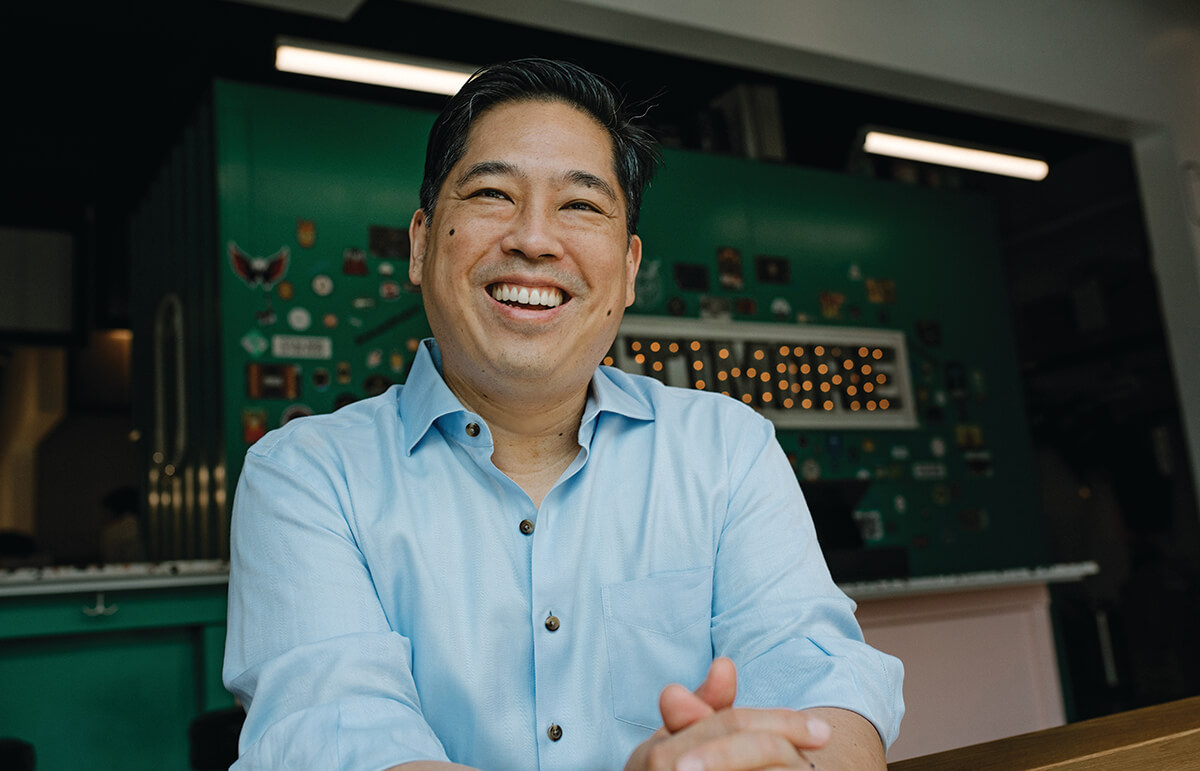

“I hate to overstate this,” says Hsu, a successful 20-year Silicon Valley executive who Catalyte founder Michael Rosenbaum essentially recruited to run the company in 2016, “but it is kind of a unique situation when you can truly say that every employee that you hire in a company is a potential game changer.”

Despite its seemingly too-good-to-be-true job ads, Catalyte, a 700-plus employee company headquartered in the Federal Reserve Bank building downtown, has trained over 1,000 software developers from non-traditional backgrounds and has offices in eight cities across the U.S., though it’s been an almost exclusively remote operation during the pandemic.

Practically, it’s a global staffing company assigning its employees to clients’ needs. Catalyte employees hold some of the most in-demand jobs in America: the people who write mobile apps, design websites, and other digital programs and platforms that tens of millions of people use every day. More relevant to people like Reed, however, is how Catalyte uses an artificial intelligence-based screening process that sees no color or pedigree, only the potential of people who take the screening.

“Extraordinary tech talent from unexpected places,” reads the tagline on Catalyte’s website.

The reach of their work is remarkable. Once the company hires someone, they may go to work on contract or full-time for clients that have ranged from sportswear giants to digital payment firms and large health insurers.

This year, Hsu launched a software training partnership with Baltimore City’s new Chief Information Officer Todd Carter, the city’s health department, and Baltimore Corps.

The effort has already trained more than a dozen Baltimore residents to be developers and work directly for the city to modernize its IT infrastructure, a long overdue need and a job-creation vehicle.

“The city was never able to hire engineers, they couldn’t afford them,” says Hsu, whose last company, San Jose-based Symbio, a research and development outsourcing firm, employed 23,000 employees worldwide. “Now we’re actually building this great pipeline of Baltimore residents that we’ve retrained to be developers and go work in the city.”

The program started with helping the city recover from 2019’s crippling ransomware attack. This year, members of this same software team helped create COVID-19 vaccine appointment and testing-result processing software, which went beyond the scope of their original assignment.

Reed’s tale of employment is one of hundreds. Alicia Waide, a Black mother of two who went to Coppin State on a full academic scholarship two decades ago, was a Baltimore City public school science teacher for 16 years when she decided to switch careers a few years ago. She had never heard of Catalyte until she had a guest speaker in class one day who spoke about the software development field and mentioned the company’s name.

“I HATE TO OVERSTATE THIS, BUT IT IS KIND OF A UNIQUE SITUATION WHEN YOU CAN TRULY SAY THAT EVERY EMPLOYEE THAT YOU HIRE IN A COMPANY IS A POTENTIAL GAME CHANGER.”

While on a summer break, she researched the company a bit more deeply, and decided to take the screening. In late 2017, she entered training. Today she says, “I’m a very happy person,” and has been working remotely at home for the last year building cloud-based applications in Java and Python coding languages.

Another example was Chris Crosby, who was a senior at Severna Park High School in 2015 when he first saw an ad for Catalyte while he was looking for a job that could help him pay for college. Like Reed, he found it on Craigslist and also “thought this has to be fake,” he says, especially given the guarantees.

The only thing that gave him confidence it was real was that the ad said the office was located in the Federal Reserve building, a bold lie if it were one. Eventually, Crosby decided to eschew attending college and work for Catalyte instead. He’s now 24 years old, debt-free, and working as a front-end website developer.

What Catalyte is doing is showing how education and employment can really work for everyone involved, meeting a demand (about 1 million software development jobs available today) with talent, and proving an academic theory that Rosenbaum, Catalyte’s founder, hypothesized two decades ago as a Harvard fellow and while working as an economic advisor in the Clinton White House.

His argument? That underserved, largely minority urban communities weren’t just places to build retail stores to generate spending, as was the prevailing thought. He saw greater opportunity in these areas because of the many people with individual talent who could contribute to an innovative labor force as much as anyone with an expensive college degree.

So, Rosenbaum decided to move to nearby Baltimore to test his thesis with a real-world experiment, and founded what was then called Catalyst IT Services.

He was right: Two decades later, nearly three-quarters of the roughly 1,000 people who have finished the company’s training program had no previous technology background; roughly 50 percent didn’t have a four-year college degree, which many think is a requirement for an in-demand sector such as software engineering; and 23 percent of Catalyte’s roughly 700 developers are women and 10 percent are Black.

“WE COULD TAKE PEOPLE FROM ALL WALKS OF LIFE AND TURN THEM INTO HIGH-PERFORMING ENGINEERS.”

“At first, I actually thought I was being sold a story,” says Hsu. He was ready to retire early with his wife and children to Sweden, with designs on publishing an architecture magazine for fun, but was stopped in his tracks after meeting Rosenbaum while looking at potential “retirement” investments and then visiting Catalyte’s offices.

The scenes—and the employees’ stories he learned—reminded him of his dad, an economist who immigrated from Taiwan with Hsu’s mother in the early 1970s when Hsu was just a 1-year-old.

Back then, his father took an entry-level job at Ford Motor Company, which then trained him to be an engineer and led the family to Silicon Valley.

“Within minutes of walking in the door at Catalyte, I was blown away by what I saw,” Hsu says. “Software engineering teams are mostly white and Asian men. I was just shocked and when I started digging into the data behind it, what they were doing was every bit as sophisticated and complex as the work that my old company was doing.”

Hsu also saw that Catalyte was providing a solution for hiring, which at the time, was “the biggest impediment in my old business.”

At Catalyte, hiring means using no human recruiters and instead is based on that digital screening process which Rosenbaum developed, taking bias out of the process.

“I couldn’t let go of that idea,” Hsu says. “Here’s a model that could really scale the whole way companies build and acquire their entire workforce. Then, of course, there’s the incredible social outcomes that continue to happen.”

“The opportunity gap is the sort of root cause of so many of the social issues we’re facing as a country today,” says Hsu. “We could take people from all walks of life and turn them into high-performing engineers. It’s a business model that you can truly say that you can do very well by doing good. The more we do the right thing, the better the business becomes.”