Nneka N’Namdi wants Baltimore to see the bigger picture.

By Grace Hebron

Photography by Schaun Champion

Five years ago, Nneka N’Namdi watched as children rode their bikes along a demolition site. As they crossed Fremont Avenue to Lafayette Street, where four large brownstones were being razed, the bikers rode past hazardous debris and gaping, six-foot holes in the ground.

The urban decay she witnessed that day—it happened to be Mother’s Day weekend—inspired N’namdi to launch Fight Blight Bmore (FBB), an advocacy group aimed at eradicating blight by creating safer spaces for Baltimore residents. More recently, these efforts have included a push for more equitable housing practices, with focuses on community development, estate planning advocacy, and dismantling the city’s ties to systemic racism.

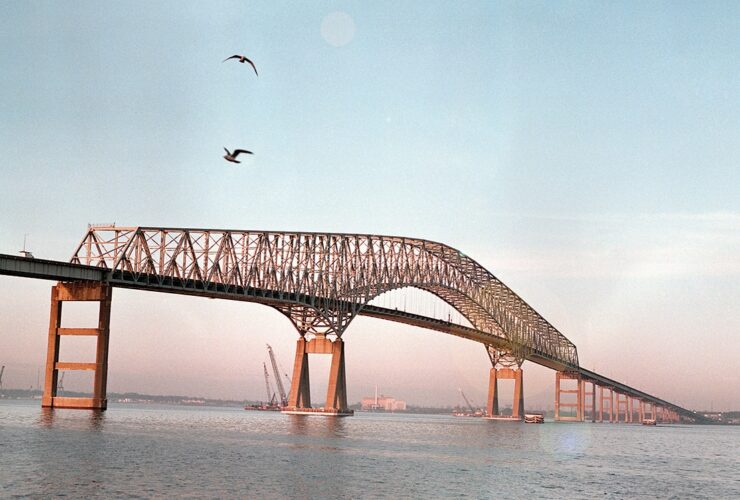

“Being a port city where you have all the different geographical types—except for frozen tundra—Baltimore could really live up to its natural promise,” says N’namdi, who lives in old West Baltimore, one of Baltimore City’s most run-down areas. “But it will never be what it could be, due to the displacement and the genocide of indigenous Americans, and the enslavement and oppression of Africa-descended people. Until those things are dealt with, we can forget it.”

Her first goal on this quest was just wrapping her head around the scope of the problem. And her track record in multiple fields helped: She’s COO of systems engineering firm N’namdi Consulting, an entrepreneur with more than 15 years of experience in community arts and wellness program development, and also a licensed real estate agent.

“In 2019, I estimated that Baltimore City had three times the reported number of blighted properties,” she says. “Things are much the same today as they were two years ago. I think the most significant change has been the ramping up of the governor’s program, Project CORE, which really seeks to use demolition as a primary strategy for remediation. Unfortunately, this doesn’t really fix the problem. It just creates a new version of it. What needs to change is that there has to be a more holistic focus on community development, which effectively means investing in people and community in ways that will enable them to create the community that they want.”

The pandemic certainly didn’t help, either, upending the priorities and finances of the city. But N’Namdi has a few strategies in mind.

“Being a port city where you have all the different geographical types—except for frozen tundra—Baltimore could really live up to its natural promise.

“But it will never be what it could be, due to the displacement and the genocide of indigenous Americans, and the enslavement and oppression of Africa-descended people. Until those things are dealt with, we can forget it.”

“One of the things that we’re really focused on is continuing the call to the mayor and local elected officials, as well as state elected officials, to do away with the tax sale [the forced sale of property for unpaid taxes], and to create a more equitable collection system for property taxes,” she says. “This will help to stabilize the community, stabilize families, and make people less housing-insecure.”

Equitable appraisals would help, too, she says.

“We’ve seen the devaluing of property, which makes people housing insecure.” Low appraisals also make it hard for developers to borrow rehab money against the value of a property, she says.

But she’s seeing some progress, especially when it comes to public awareness of the long-term negative consequences of urban decay and neglect.

“People are really starting to make the connection between what a neighborhood looks like, and public policy priorities,” she says. “More people are reaching out to us. And some of the language that we are hearing folks use really focuses on blight in the same realm as other social determinants of health.”

The radical inequalities between neighborhoods also affects things like life expectancy: In neighborhoods like Sandtown-Winchester, it’s 10-20 years less than in some of the city’s stable neighborhoods, according to FBB.

“Let’s start with water,” she says. “Because Baltimore is under consent decree with the EPA, the cost of water is high,” she says. “That’s limiting folks’ access to this resource that we all need to live. But if you look at Sandtown-Winchester, people live under food apartheid, meaning that there’s no accessible grocery store within a quarter mile of that neighborhood.

Your water costs are high. Your access to nutritious food is low. And then, because of poor transportation infrastructure, you have to travel farther for school. If you can’t bathe or drink water, if you can’t eat nutritious food, if you have challenges getting to school and work, what quality of life are you going to have?”

And the list goes on: “Many of these blighted neighborhoods are also heat islands,” N’Namdi says, “which means because there’s a lack of tree canopy, and because we have tar roofs, these neighborhoods have temperatures that are six degrees higher. So when you compare Sandtown-Winchester to Roland Park, you see starkly different physical conditions. The outcome is lower life expectancies.”

All of those obstacles can also contribute to mental-health problems, she says.

“Your community is a reflection, oftentimes, of how you see yourself. By allowing these communities to look this way, we’re teaching people that there’s something wrong with them, and that is not correct. There’s some- thing wrong instead with the conditions in which people find themselves living. And it is extremely traumatic to have to navigate these spaces, to walk past buildings that look like they might fall down if the wind blows too hard. Or to walk past grass that’s taller than you in a city where we have three times the national average of childhood asthma. That makes navigating the school, navigating home, and going outside traumatic. It damages people’s ability to feel and to think, and therefore, to have a good, healthy and whole life.”

Despite all the challenges, N’Namdi has remained remarkably hopeful there will be progress.

“My hope is that Baltimore takes a good, hard look. This is an opportunity for Baltimore, to be one of the first major American cities to come out of that process with some reparative policy so that we don’t continue taking these complex and compound traumas forward. I do hope that we begin to see this come to fruition in the next several years. It can be done.”