More Than A Coach

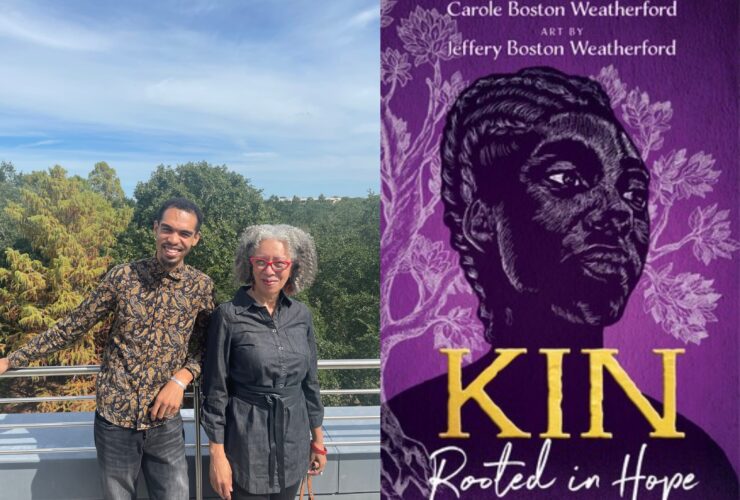

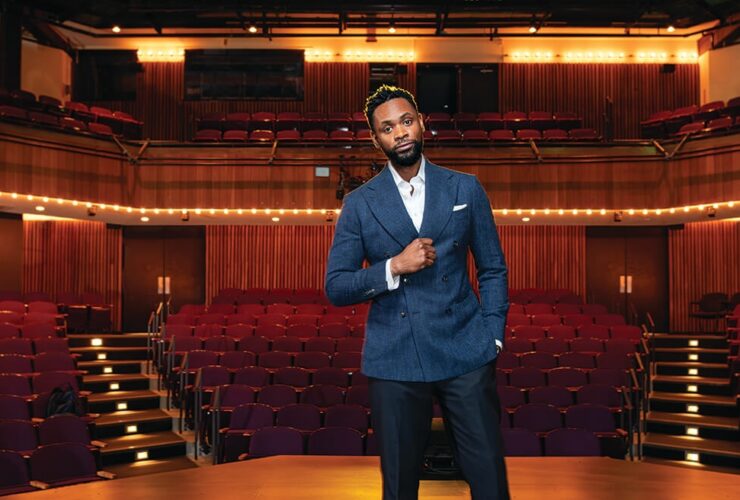

Garrick Williams, the “Mayor of Park Heights,” teaches life lessons through football

GameChangers

More Than A Coach

Garrick Williams, the “Mayor of Park Heights,” teaches life lessons through football

He’s right. When you stand in the center of this football field in Northwest Baltimore, the grass framed by the backs of rowhouses, a pair of field-goal posts, and oak trees with leaves turning shades of yellow, orange, and red on a chilly late fall day, “You can feel the peace,” says Garrick Williams, the 62-year-old founder of the Park Heights Saints youth football program.

Widely known as the “Mayor of Park Heights,” a description he acknowledges with a wisecrack (“It ain’t an easy job,” he says), Williams, a one-time construction worker turned neighborhood do-gooder, is standing near the center of this piece of land in Lucille Park along Reisterstown Road on an early Friday evening in November. Twenty years ago, this was a notorious abandoned lot populated by drug dealers and addicts. And, even more recently, a bar used to operate on the park’s northeast corner, but it was razed seven years ago at Williams’ urging in favor of a parking lot. That’s where kids now get dropped off three nights a week for practices, led by Williams and dozens of other coaches, some of them former players, others former gang members, yet others Baltimore City police officers.

Not a fan of the cold, the “Mayor” is wearing several layers of Under Armour athletic gear, pants, and a knit hat and greets you with the dap of a lifelong friend. “That’s right, brother, that’s right,” he’s soon saying. Practice, for the Saints’ 10 teams made up of about 250 players ages 5 to 13, will start in an hour. So for now, Williams is happy to stroll around the field and soak up the scene, coach’s clipboard in hand.

He’s talking about the year’s worth of Jericho walks—meaning going seven times around the field—that community members did back in 2000 to take control of the field, when he pauses near the 50-yard line, his back to a setting sun, and puts the existence of this refuge in perspective. A quarter of the residents of zip code 21215, the primarily black neighborhood that abuts Pimlico Race Course, live in poverty, making it a breeding ground for violence, gang recruitment, and drug dealing in the surrounding houses and blocks.

“Things still go on in Park Heights, but it won’t go on here,” Williams says of the field. “This is like a sanctuary.”

Williams is a youth football coach with hundreds of children and roughly 45 coaches under his supervision per year but, without any hyperbole, he is much more. “To know him is to love him,” says Kiante Chase, an electrician from Dundalk and a father of three who coaches the Saints’ under-11-year-old team.

Williams has lived in the neighborhood for more than three decades with his wife, Theresa, and has been a community liaison and youth outreach worker for the past 18 years at nearby Sinai Hospital. He’s an evangelical minister, a violence-prevention mentor at area schools, like KIPP Academy, and has won various awards for service and leadership. But a lot of what he does goes unnoticed, like organizing a food drive a few weeks ago at the field, and handing out flyers on the street to promote it.

“He’s always saying, ‘It ain’t about me, it’s about these kids,’” says Sirena Alford, the Baltimore City representative for the nonprofit organization Fellowship of Christian Athletes, which administers the Saints’ program. “But he still is the voice for them.”

In high school, Williams played football, baseball, and basketball at Carver Vocational-Technical High School, but had no intentions of coaching any sports until his son started playing football in the late 1990s. By that time, Williams had already started to cultivate his faith through the Agape Miracle Church in Park Heights, after being recruited while walking past one day on the sidewalk. He put two and two together, realizing football could be a vehicle to spread the good word. He started going by the name “Coach G” or “Brother G.”

“The kids are going to follow the coaches,” Williams says. “I thought I could use this as a ministry. They want to know football, I want them to know Christ and life.”

Importantly, the “Home of the Saints,” as the banner says near its entrance, is by no coincidence located right near the site of the church that Williams joined 30 years ago. It’s also close to his own house, where he and his wife raised their three children.

Most notably, though, a two-minute walk will bring you to 4804 Reisterstown Road. The 2,000-square-foot home is essentially a brand new three-story gathering place for all the kids in the Park Heights youth football program. It’s open every Wednesday after school, and functions as another sanctuary for kids growing up in an area where the life expectancy is more than 10 years shorter than for those living in upper-middle-class Mount Washington a mile away.

The home was once the site of a nondenominational ministry and food pantry, where Williams and many others were discipled by the late Rev. Eleanor Bryant, but the building had fallen into disrepair in recent years, like many others in the neighborhood. One night four years ago, Williams had a dream to remodel the house into a place Saints’ players could feel safe in.

“On September 30, 2015, at 1 in the morning, the Lord allowed me to dream,” Williams typed on a computer the next morning. “This is what he showed me.”

A living room with a white leather sofa and chairs. A big TV. A nice kitchen. Upstairs, a computer room and a bedroom, should it be needed. And a weight room in the basement and a deck out back. It’s now a reality, thanks to private donors and volunteers and an effort led by local businessman Frank Kelly III and the Fellowship of Christian Athletes: The roughly $250,000 Park Heights Saints Community Center opened its front door in March.

William typically repeats what sound like Bible verses every day, but they’re not: “Your first name is choices, your last name is consequences;” “The world doesn’t owe you anything. You owe yourself everything;” “The two words that make a real man? Responsibility and commitment.”

He repeats “Brother G’s Pledges” before every practice, when he gathers kids beneath a tree for a sermon of sorts. He conveys wisdom with almost every sentence he delivers, about big broad themes like right and wrong, joy and pain, life and death.

“Group talks, he calls them,” says 13-year-old Kylan Duppins, who attends KIPP Academy, is a lineman for the Saints, and lives around the corner. “He talks about things like, don’t take life for granted because some people didn’t wake up this morning. Love your family because one day you might not have them.”

Williams knows. As a toddler, his father was shot and killed during an argument at a party, and his stepfather and mother separated when he was a teenager. It’s an all-too-familiar tale around here.

“A lot of the kids don’t have both parents. Sometimes they don’t have one,” Chase says. “It’s a bad area. We got kids from all over, but the majority of the kids come from broken homes.”

Others involved in the program share their stories, too. Antonio DeShields, 39, a former Division I football recruit at Cardinal Gibbons who grew up on Virginia Avenue in Park Heights, nearly died as a high school senior. Hospital workers ruptured an artery in his leg while popping a knee injured during a football game back into place. With his scholarship offers gone, he spiraled into a suicidal depression before Williams asked him to come to a practice 19 years ago to talk to the kids.

Raymond Queen, who lost his father at age 7 to murder, became a police officer. Former player Brian Ford did, too. Several other coaches are former gang members, like Gerald Butler, the Saints’ vice president, who now manages a few real estate properties. “You got a lot of coaches that have a past, too,” he says.

Val Knight, 31, another coach, grew up in Greenmount and flunked out of Cornell University as a freshman after earning a football and lacrosse scholarship there. “I see a lot of me in a lot of these kids,” he says, “and I’m trying to get them to not make the same mistake I made.”

Tonight, though, in a rare occasion, there’s no such pre-practice huddle under the wisdom tree. It’s getting close to 6 p.m., it’s already dark, and starting at 9 tomorrow morning, all of the Saints’ teams will play in a series of local championship games at Frederick Douglass High School. In other words, time is short. But the lessons aren’t. As dozens of kids arrive, from tiny tots to teenagers with who-knows-what on their minds, we ask Coach G a simple question: Isn’t all this hard?

“Hard?” he says, “Everything’s hard, but it’s about having a purpose. If you don’t have a purpose to live, you’ll just die of not doing anything. I love people. I don’t do this for my own accolades. I do it because I want to change the community. I want to change lifestyles, and this is how you get the message across. That’s my purpose. And, alongside all that, we’re winners.”