In 2010, Marco Ávila won a quarter million dollars from the Maryland Lottery by playing five winning numbers. Some would call it good luck. Others might call it karma.

You see, when Ávila, who hails from Ecuador, first came to America to go to school in 1981, he had nothing. What’s more, “I didn’t speak a lick of English,” he says.

He immediately enrolled in an ESL school, taking some nine different courses including phonetics, composition, and writing to become fluent before beginning at the New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT).

When his mother told him she was going to get a second job to help pay for his education, he told her he wouldn’t take another penny from her. He chose, instead, to work manual labor jobs on construction sites and in factories, despite his aversion to getting dirty.

He routinely went to the school registrar’s office with cash payments in hand from the jobs he was working. He graduated from NJIT in 1993 without student loans.

“My days would start at 7 a.m. and go to 11 p.m.,” he remembers. “Right out of work, I’d go straight to school.”

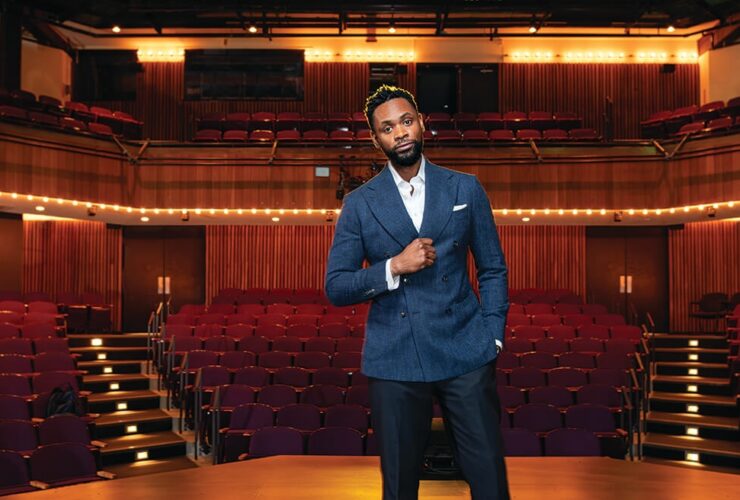

While studying civil engineering, Ávila applied for—and ultimately got—an entry level position to be a draftsman. He eventually worked his way up the ladder to become a highway engineer. With a steady income and a 9-to-5 job, Ávila soon found he had time on his hands.

Ávila started traveling, including a trip back to his home country. On a trip in 1994, he met some traveling doctors returning from a medical mission. Ávila was soon recruited by the group as a translator. In 1995, he traveled to Puyo, Ecuador, for his first medical mission and spent the next decade translating on missions with the team.

In 2005, work moved Ávila with his family from New Jersey to Maryland where his first project was the Interstate 95 (I-95) Express Toll Lanes in White Marsh. Though his career was humming along as smoothly as he hoped to make I-95’s traffic, those years working in medical missions continued to inform Ávila’s philanthropy.

Ávila had remained close friends with a surgeon, Dr. Jaime Flores, whom he met on his first mission to Puyo. The two continued to go on missions together over the years, Ávila as the translator, photographer, videographer, and logistics coordinator, and Flores, a plastic surgeon performing reconstructive surgeries for children such as cleft palate.

“We had this energy together,” describes Flores. “We had the same mission of helping people purely out of the goodness of our hearts. There was a gleam in our eyes, and out of all the volunteers, he and I [after 10 years] were like, ‘We can make medical missions better.’”

So, in 2007, along with pediatric surgeon Dr. Dylan Stewart, and an NICU nurse, Susan Connolly, Ávila and Flores founded The Healing Hands Foundation. Their mission: to expand medical missions beyond Ecuador, to sustainably provide high-quality surgical procedures, and to build long-term relationships with the local community.

“We wanted to do more than a mission in Ecuador,” Flores says. “We wrote duties, bylaws, and 2007 was the first time we did the missions under The Healing Hands Foundation.”

The same year Ávila founded The Healing Hands Foundation, he brought together the engineering community—he was now a civil engineer and director and program manager at WSP, one of the world’s leading engineering and professional services consulting firms—to support his good works through Golfers for Charity.

This annual event, now in its 15th year, is played at the Greystone Golf Course in White Hall and has raised about $750,000 in support of The Healing Hands Foundation and several other charitable organizations such as Ronald McDonald House of Maryland.

“I always think that everything in your life, whether professionally, personally, humanitarian, volunteering—it’s all connected,” Ávila notes.

And connected it was. It was through The Healing Hands Foundation that Ávila became involved with the Maryland Hispanic Chamber of Commerce (MHCC), whose work is to further promote the growth, prosperity, and retention of Hispanic businesses in the state by providing advocacy, resources, and networking. In April 2019, Ávila was named chair of the board and president of the MHCC.

“Marco is well-recognized, connected,” says María Pílar Rodríguez, a longtime member of the MHCC and now the executive director under Ávila’s leadership. “He is the community leader and has their best interest [at heart], unselfishly helping people.”

When Ávila started in his leadership role at the MHCC, membership had dwindled to just 89 members and the organization was near bankruptcy. His first goal as chairman and president was to raise the membership number to 1,000.

“Marco always reinforces this goal to the board—to become the biggest chamber—and we’re working toward that,” says Pílar Rodríguez. “Because of his leadership, we have gotten some great sponsorships from the University of Maryland Medical System and Verizon. They are now repeat sponsors. Before we ask, they’re coming back to us to help fund programs.”

One out of 15 jobs in the region is created by Hispanic businesses. Having a solid chamber supporting those businesses is essential to cultivating positive economic development for this growing demographic.

For example, one of the goals of the MHCC is to educate small businesses on how to obtain certification as a Minority Business Enterprise and bid on government contracts.

“Right now, I have the best of both worlds,” Ávila says. “I work for a big global company, but at the same time, I’m helping the small businesses that typically are trying to be a subcontractor under a big global company, and I can help through this volunteer work [at the MHCC].”

Under Ávila’s leadership, the MHCC set a goal to grow to nearly 800 members in 2022. Ávila notes that when it hits that mark, the MHCC will, indeed, become the biggest chamber in Maryland.

During his term, which the MHCC has already extended for at least another year, he established a scholarship fund to support Hispanic students in high school, college, and trade school. He’s committed to ensuring that the MHCC runs with continuity even when he steps down.

“I want to make sure we finish what we started, to keep it going,” he says. “The greatest gift you can give to others is the example of your own life. I’m excited to continue to grow the next generation of leaders to make a difference in our state.”

Unsurprisingly, when Ávila won that quarter of a million dollars from the Maryland Lottery, he gave away a portion of his winnings to his Healing Hands Foundation.