GameChangers

Diets of Debris

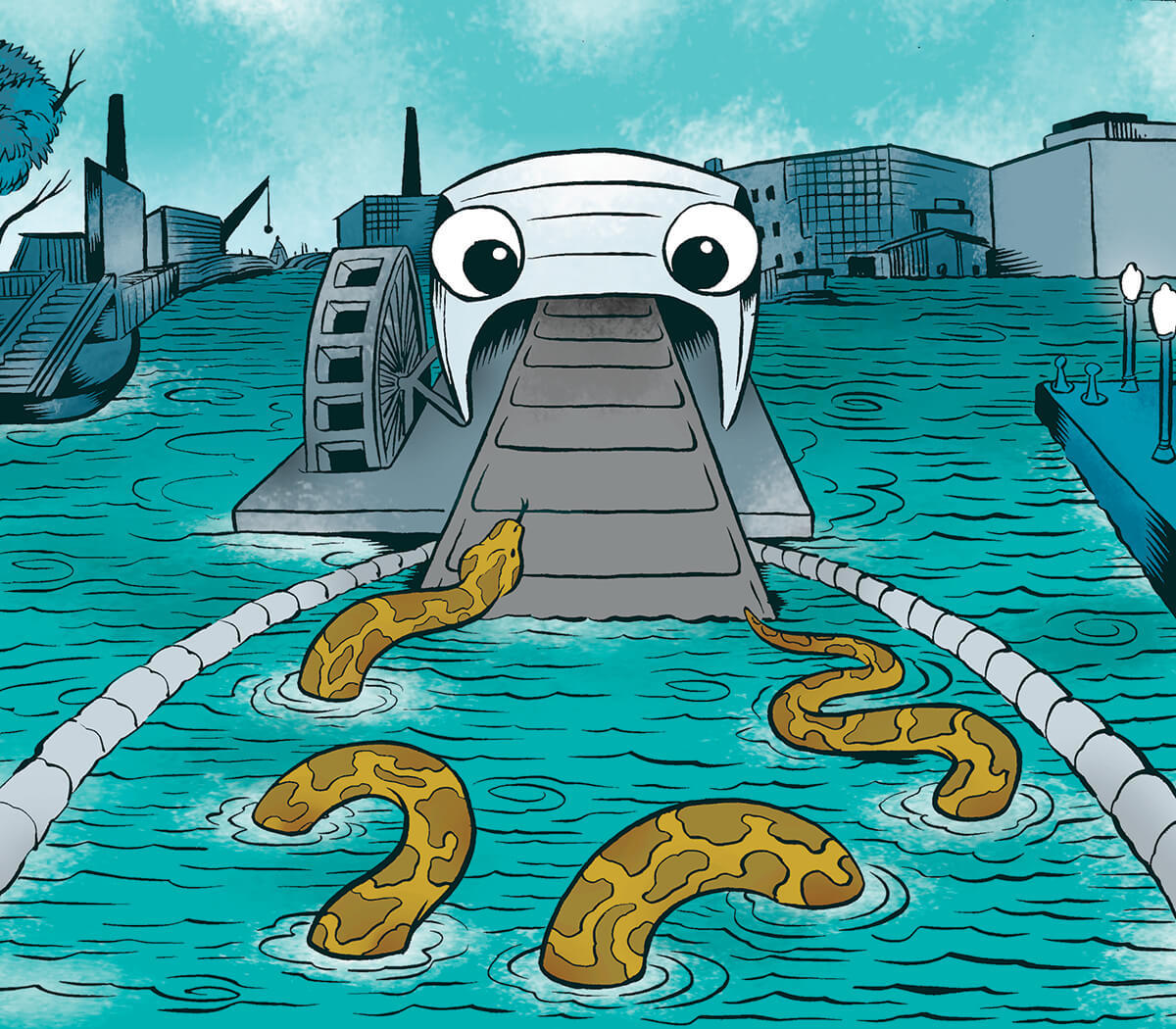

Thanks to its steady refuse-noshing, Mr. Trash Wheel makes the harbor cleaner.

Adam Lindquist remembers the time Mr. Trash Wheel picked up a

ball python. The West African snake, presumably someone’s escaped pet, had found its way to the Inner Harbor and was scooped up by the animated machine that labors where the Jones Falls meets the Chesapeake Bay. And that turned into a marketing moment: The interloper inspired Peabody Heights Brewery’s Lost Python Indian Pale Ale.

The 50-ton googly-eyed anthropomorphic water wheel annually intercepts some 200 tons of garbage—including all manner of plastics, tires, and even the occasional mattress. He’s just one project from the Healthy Harbor Initiative, designed to protect the Baltimore shoreline. The organization also runs the Great Baltimore Oyster Partnership, which planted its millionth bivalve in summer 2019—though the filter feeders are not for human consumption. Then there’s the nonprofit’s Harbor Scholars program, launched this school year with funding from the Chesapeake Bay Trust, which educates some 700 Baltimore fifth-graders about environmental issues and practices.

But with about 60,000 social media followers and counting,

Mr. Trash Wheel—one of three contraptions at work on Baltimore’s waterways, and there’s a fourth on the way—remains the most visible part of the campaign, says Lindquist. “Mr. Trash Wheel is a mascot for environmentalists around Baltimore.”

Launched in 2010 by economic development group Waterfront Partnership, Healthy Harbor has the target of “Swimmable by 2020” and that goal now looks achievable. Baltimore City’s $1 billion in infrastructure funding, including a $200-million loan from the Environmental Protection Agency, will fund upgrades to reduce sewage over flows and rainwater runoff, Lindquist says. “But there’s always more work to be done.” Even if the harbor is safe for humans, the levels of phosphorous, nitrogen, and sediment continue to put plants and animals at risk.

Healthy Harbor’s next goals include a focus on “green” solutions, such

as more green spaces and fewer impermeable surfaces, like sidewalks and parking lots.

The lumbering amphibian was invented by John Kellett of Clearwater Mills in Pasadena, but a marketing rm suggested the personality, Lindquist says. He himself created the prototype. “I made the first googly eyes in my basement out of insulation board,” he says. “Then we found a company to make them out of metal.”