![]() ack when she was in high school at Baltimore City College, a college prep school in northeast Baltimore, Unique Robinson remembers that each year, guidance counselors would ask students what they wanted to be in life. When she wrote “poet” every time, they would respond, “You can’t make money from that.” Robinson’s retort was, “It doesn’t matter. This is what I want to do.”

ack when she was in high school at Baltimore City College, a college prep school in northeast Baltimore, Unique Robinson remembers that each year, guidance counselors would ask students what they wanted to be in life. When she wrote “poet” every time, they would respond, “You can’t make money from that.” Robinson’s retort was, “It doesn’t matter. This is what I want to do.”

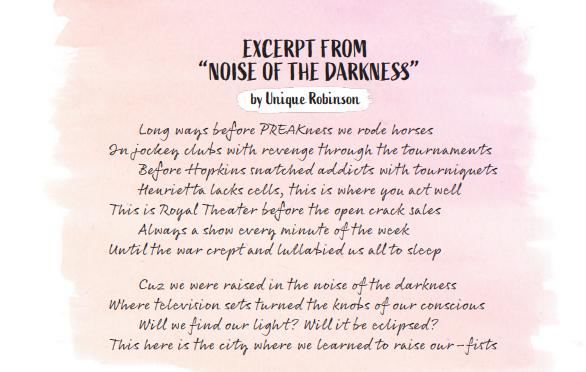

Robinson, 34, officially chose her vocation at age 10 when she was attending Arlington Elementary School. “That’s where I discovered I wanted to be a poet, because we had a funny-titled standardized test called ‘You’re a Poet and You Don’t Know It.’ I can’t make this up,” she says with a laugh. “That’s literally when I started writing poetry, from that point on.”

Luckily for the Pride Center of Maryland, the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA), and the local LGBTQ+ community, Robinson was stubborn and determined to not only be a poet, but to teach poetry to others.

Born in Baltimore City, Robinson lived her first few years at Lexington Terrace, the public housing project that has since been demolished. When she was 3 years old, Robinson moved with her mother, Carla Singletary, to Park Heights.

“I loved growing up going to the corner store and getting frozen cups and eating the local food—cheesesteaks, seafood. I had a really fun childhood overall,” she recalls. But her working-class family also often dealt with a lot of the systemic racism going on at the time. “I wasn’t really a child who opened up about a lot of my emotions. So writing became my outlet to do so,” says Robinson.

At 14, she began doing spoken-word poetry. “I performed my first poem, and I haven’t stopped performing since.” After graduating from Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts, where she studied creative writing and African-American studies, Robinson lived in Brooklyn, New York, where she worked as a community organizer. That work has informed her art as well as her approach to teaching.

Robinson then headed to Oakland, California, to earn her M.F.A. in creative writing and poetry at Mills College. Upon graduation, Robinson returned to Baltimore in 2015. Home, and her life’s work, had come calling.

Teaching was a way for Robinson to give back to the community. She taught poetry at DewMore Baltimore, a nonprofit started by her longtime friend, Kenneth Something. This led to her teaching at MICA for the last six years, where she’s been on the faculty in Humanistic Studies, “essentially all the courses that aren’t studio courses,” she says. “Critical theory, creative writing, academic writing workshops.”

Besides teaching at MICA, Robinson is a teaching artist with Arts Every Day. Teachers in Baltimore City Schools can contact her, and she will do writing workshops with their students—from third to 12th grades. Robinson also conducts arts integration workshops, where she merges poetry with history and visual art. At the nonprofit arts collective Motor House, she teaches a free writing workshop. In the past, Robinson has taught at Towson University, Wide Angle Youth Media, and Leaders of Tomorrow Youth Center.

“I honestly can’t picture my life not being an artist and teacher,” she says.

While she is passionate about her career, Robinson didn’t expect to be a teacher. She was inspired by her grandmother, Virginia Whitehead, who taught for 40 years in Baltimore City Public Schools. Her mother also encouraged her by saying, “Dare to be different,” giving her the name Unique to remind her of that, and supporting her decision to pursue poetry and education.

![]() oday, Robinson pays that inspiration forward through her work with students of all ages. Being encouraging is crucial in teaching, Robinson says. “I remember what it was like when people put my fire out, and I didn’t like that feeling,” she recalls. “This is a time to inspire people to do the things that scare them, but not scare them away from it. Critique is a natural part of being an artist, but there’s a way to do it that’s empowering. I always do the sandwich method: You start off with something that’s positive, then move to something they might need to work on, and then continue with something that’s positive again.”

oday, Robinson pays that inspiration forward through her work with students of all ages. Being encouraging is crucial in teaching, Robinson says. “I remember what it was like when people put my fire out, and I didn’t like that feeling,” she recalls. “This is a time to inspire people to do the things that scare them, but not scare them away from it. Critique is a natural part of being an artist, but there’s a way to do it that’s empowering. I always do the sandwich method: You start off with something that’s positive, then move to something they might need to work on, and then continue with something that’s positive again.”

Through this work, she’s sometimes saved lives. “There are students I worked with that I met at a particular junction of their lives, when they were thinking, ‘I don’t want to be here. I don’t want to live. I’m done.’ Through writing, I’ve essentially helped talk people off their own cliffs,” says Robinson. “I don’t take that lightly. I think of that as the power of what that work can do. It opens them up to another side of themselves, and it can spark and inspire someone else to continue on. I can’t believe that I get to have that kind of influence on people. It’s still mind-blowing to me.”

That kind of power and influence doesn’t end in the classroom or during a workshop. Robinson continues to be an inspiration for the LGBTQ+ community at large, as an unapologetically and openly gay woman of color.

“As a Black queer person, I think that we spend a lot of time in hiding. As someone who has been out since I was about 16 years old, once I was out, that was it,” says Robinson.

Robinson’s combined background in advocacy, arts, and education made her the perfect pick when, in 2016, her friend Something was co-executive director at the Pride Center of Maryland (PCOM) and needed a host for an open-mic night called Giovanni’s Room. (The name comes from the James Baldwin novel that reflects on homosexuality and bisexuality.) Lasting for two years, it was the longest-running LGBTQ+ open-mic series.

Something, who is now the director of programs with the Black Arts District and the director of partnerships and special events for PCOM, says that he likes Robinson most because of “her brilliance, while at the same time her humility.” She never loses sight of the purpose behind her work.

“It’s never about her,” he says. “It’s always about doing phenomenal work in the community. She’s just genuinely, authentically humble.”

As part of the other programs PCOM started, Robinson ran a writing workshop for LGBTQ+ folks in the community. Also called Giovanni’s Room, the group gave people a space to write and workshop their writing that they would otherwise have lacked. “Writing workshops are few and far between unless you’re in a school program,” says Robinson.

In June 2021, Robinson was asked to chair Baltimore Black Pride, which was held in October of that year and sponsored by the Black Arts District and Black Equity Baltimore. “Baltimore has a huge population of Black LGBTQ+ folks. We just wanted a space for them to celebrate,” she says.

Robinson and her team had events, workshops, a karaoke night, and concerts, featuring local acts such as Kotic Couture, DDm, and RoVo Monty. They even were able to connect with Stonewall International Poetry Slam, the world-renowned poetry festival that was coming to Baltimore during the same week as Baltimore Black Pride.

“I felt a personal sense of pride in bringing amazing and high-quality events to Baltimore, as well as to the folks who were visiting Baltimore—to give them a different side of what Baltimore is and what they could expect out of the city,” Robinson says. “We highlighted and showcased how Baltimore is an arts and cultural beacon around the world.”

After folks at PCOM saw what she had done, Robinson was hired part-time as assistant Pride coordinator for Baltimore’s celebration of Pride Month held each June. This year’s theme was “Together Again for Pride.” Robinson says that she especially enjoyed discovering all the ins and outs that go into creating a festival for more than 60,000 people, gathering the expertise of LGBTQ+ folks citywide, and for being back in person. Most in-person Pride events, such as the parade, have not been held since 2019 due to the pandemic.

“Pride is all about giving people space to celebrate who they truly are, and Unique creates that same experience for everyone that she encounters on a daily basis,” says Mary Miles, a friend and volunteer on the Pride committee. “Pride is not simply a day or weekend recognition—she lives those values every day.”

“Pride has always represented a time for LGBTQ+ folks to be their freest, most authentic selves, and even still, carries a legacy of resistance to silencing of our voices, our bodies, and our expressions,” says Robinson. “It was intentional for me to be openly queer, but it just sort of came together to be an inspiration that way, not just for myself, but for other young people who might come up behind me. As a person, as a professional, it is a huge part of my identity. So to be able to utilize it for the greater good of other LGBTQ+ folks in the city is, I think, the biggest part of Pride for me.”

Whether she’s writing poetry or performing it, making a difference with students through teaching, or bringing Pride to Baltimore, Robinson is doing exactly what she’s always wanted to do, and the community reaps the rewards.