Weaving new relationships by connecting people from different communities

GameChangers

Thread

Weaving new relationships by connecting people from different communities

When Steven Clapp was in Ninth grade at Dunbar High School, a woman came into band class and read off a list of students’ names. “I was playing snare drum and minding my own business,” Clapp, now 20, says. “She told us to follow her. I thought I was in trouble.”

The woman, who, it turns out, was employed by a nonprofit, led them to another room, where she said, “You’re gonna take this quiz, you’re gonna eat this pizza, and you’re gonna like it,” Clapp recalls.

The chosen students, identified as “high potential, low performers,” he says, had been selected to participate in Thread, an organization that provides a network of support to each student, committing to the student in various ways for 10 years.

Clapp, pictured, who didn’t have money for food that day, did as he was told and liked it. Not just the pizza, though that seems to have been a valued perk. “Thread drowned us in pizza,” he says. “Plus, we got Chipotle at midterms and finals.”

But the relationship didn’t end with a free lunch: Over the years that he’s been involved with Thread, he’s received all sorts of support—everything from a lift from Dunbar (in East Baltimore) to his brother’s house in Pikesville, to help with homework, to just having someone to hang out with on a summer afternoon. “If it weren’t for Thread, I’d be working at Wendy’s,” says Clapp, who currently freelances as a music producer and helps market a new app affiliated with Thread.

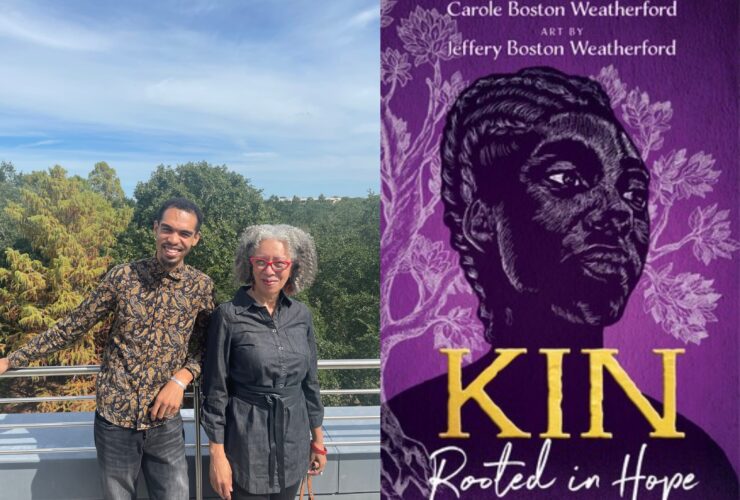

Today, more than two years after graduating from high school, he sits in a small meeting room at the Thread headquarters in Mondawmin Mall with Vince Talbert, one of his mentors—Thread calls them “volunteers”—to talk about the program. This time, there are donuts.

The two met in 2018 when Talbert, a tech entrepreneur who started the company Bill Me Later (which he later sold to PayPal) began developing an app to support Thread. The platform, called Thrive, is designed to help scale Thread’s activities by connecting its participants.

Talbert began his relationship with Thread as a “collaborator,” one of the three legs, along with the students and volunteers, of the Thread system. Collaborators donate their unique professional expertise—in Talbert’s case, software development. Other collaborators might include tutors or experts in law, college admissions, or job readiness. Talbert soon transitioned to volunteering with students and is now a “head of family” in Thread parlance. “Steven kind of recruited me,” Talbert explains. “We were working on the app research and he said, ‘You should be my volunteer.’” Talbert later hired Clapp to introduce students to the app.

Clapp is just one of Thread’s success stories: Founded in 2004 by wife and husband Sarah and Ryan Hemminger, when Sarah was a graduate student in biomedical engineering at the Johns Hopkins medical campus—a neighbor to Dunbar High School—they recruited volunteers from the School of Medicine to work with 15 at-risk students, helping them with whatever they needed. “We started with 15 students, two volunteers, and one high school,” she says. Initially, Thread took on new students every three years, and eventually graduated a class after three years. In 2019, 112 ninth graders entered the program.

This year, the organization will serve 735 students from six high schools with about 2,000 volunteers, says Sarah Hemminger.

“We’re trying to knit together an entirely new social fabric in the city.” By remaining alongside students through graduation and into adulthood, Thread establishes trust, she says. “We’re focused on building relationships gradually and intentionally.” Volunteers commit to at least one year, but a large number remain for two years and beyond.

Part of the nonprofit’s mission stems from Ryan, who struggled in high school after his home life took a dramatic turn. A handful of his teachers rallied around him, providing clothing, food, and even bus fare. He eventually became an A student, a varsity athlete, and a graduate of the Naval Academy.

What sets Thread apart from most mentoring programs is the concentrated and long-term involvement: four volunteers, one student, 10 years. Another critical difference, according to Allison Buchalter, Thread’s vice president of involvement: “We never call them mentors. That implies a power structure.”

Hemminger’s vision takes it a step further, seeing the relationship as a give and take. She strongly believes that volunteers benefit from their Thread families as much as the students do. Baltimore, she says, “historically has had a lot of policies that intentionally segregated us. It has created isolation—not just by race, but by class,” she says. “Thread helps to bring people together across those lines in a way that is transformational for everyone.”

“The way the narrative is usually told is there’s a group of haves who need to save the have-nots,” she continues. “But if you define the problem as social isolation, it repositions all of us to be in need and have the capacity to provide help.”

Indeed, observing Clapp, a young adult with a challenging Baltimore City childhood, and Talbert, who lives in a big house in Lutherville and drives a Tesla, it’s difficult to determine for certain who’s helping whom. Talbert recalls once complaining to Clapp that he was having a bad day: “His answer was, put on something snazzy, get out the Tesla, we’re going down to Baltimore Street.” Talbert says he passed on the night out, but was touched nonetheless. The father of two says, “You get to a point where you’ve done your job with your kids and they’re on their way. You become less important.” Of his relationship with Clapp, he says, “It’s great to matter in his life, and he matters in my life. He makes me smile every day.”

In turn, Talbert has helped Clapp reach specific goals. One was getting a driver’s license so he had more access to employment. To work in Mount Washington, five miles from his home in Park Heights, Talbert says, Clapp would have had to take buses all the way into the city and back north again. “We decided the best way to get the best job opportunities was to work on getting a license and a car,” says Talbert, who lent Clapp money for a Nissan Altima soon after the younger man passed his driving test.

Hemminger, who in 2010 passed on a position at the National Institutes of Health to work on Thread full-time, says the organization’s current goal is to change the culture of the city. “The ultimate intention is to serve 7.5 percent of all students in Baltimore City public schools,” she says. That would mean working with about 3,000 young people and about 8,000 volunteers. Once you add board members, collaborators, staff, and relatives, she says, “We’d be a community of about 20,000 Baltimoreans—or roughly 5 percent of the adult population in the city.”

In the meantime, Talbert is helping Clapp to set career goals. “I know nothing about music,” says Talbert, “but I play squash with a professor at Peabody.” After meeting with Clapp, Talbert’s squash buddy confirmed the student’s potential on the drums. “He immediately said, ‘He’s really talented,’ and he’s suggesting schools Steven could go to and professors he could work with,” Talbert says. “Now we just have to figure out the right game plan.”

“That’s really the magic of Thread,” Talbert continues. “It’s connecting people who wouldn’t otherwise be connected. Creating pathways that didn’t exist.”