Halethorpe-based nonprofit, Vehicles for Change, transforms lives with car ownership, reentry programs.

GameChangers

Into the Driver’s Seat

Halethorpe-based nonprofit, Vehicles for Change, transforms lives with car ownership, reentry programs.

Receiving the keys to her 2005 Honda Odyssey changed Janell Johnson’s life. “I felt so empowered,” she recalls of the day in 2012.

The community activist and single mother of four no longer had to leave home three hours before work in case of bus delays. And her hard-earned money could go into the gas tank rather than toward taxis.

She had a stable career working for the Department of Social Services in Anne Arundel County, but was limited by a lack of reliable transportation. “I would get these 20-year-old cars with hundreds of thousands of miles on them,” Johnson says. “They would break, and then I would just have to rely on the bus and taxi cabs.”

It’s a familiar challenge for families across the region. In Baltimore, 33 percent of residents lack access to a car. In historically disenfranchised neighborhoods, the number is much higher—around 80 percent.

Vehicles for Change, a Halethorpe-based nonprofit offering car donation and reentry internship programs for ex-prisoners, is dedicated to changing those statistics.

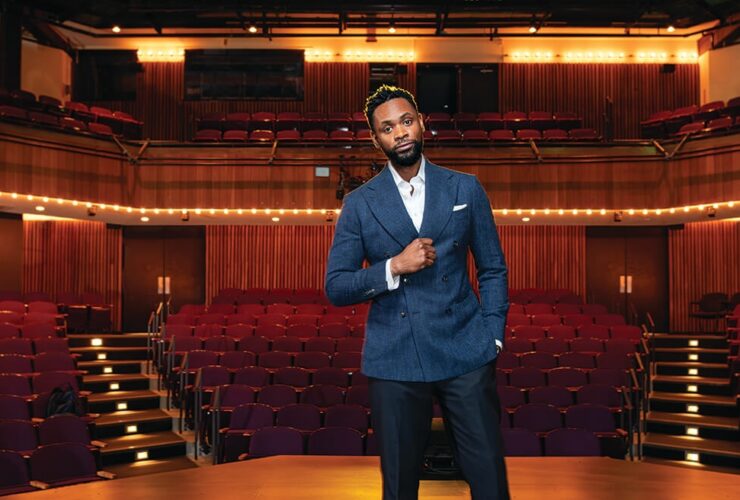

“Car ownership just opens up so many opportunities for folks,” says Marty Schwartz, president of Vehicles for Change. “Now the job market is not just within a mile or two of your house. It’s unlimited.”

He references a 2011 study by the Brookings Institute that found 71 percent of zero-car households in the Baltimore area are low-income, and that more than 6,000 car-free households also lack access to jobs via public transportation.

“People are not getting out of poverty until you get them a vehicle.”

The process works like this: Individuals and companies donate cars to Vehicles for Change, which fixes them up in its shop, then awards them to individuals who have applied to the program through local social service agencies.

“people are not getting out of poverty until you get them a vehicle.”

—marty schwartz

The cars aren’t free, but pretty close: Most vehicles provided to qualifying families cost around $900, come with a six-month, 6,000-mile warranty, and should run reliably for at least 24,000 miles or two years. Low-interest loans keep the monthly car payments around $90 and help awardees build credit.

Donated cars that aren’t great fits are used in other ways. Luxury or newer-model cars are sold through its used-car lot, Freedom Wheels, with proceeds going back to the nonprofit. Total junkers, meanwhile, are sold for scrap or parts.

Since its founding in 1999, the organization has grown from a single small space in a Beltsville warehouse to a network of shops serving communities in greater Baltimore, Washington D.C., Virginia, and even Detroit.

It awards anywhere from 300 to 350 cars per year in the Maryland and Virginia area. While the demand is much higher, they are limited by the number of donations received. “We could be awarding 1,000 cars per year, easily,” Schwartz says. “Our biggest challenge is always getting enough cars.”

Schwartz says he envisions the program expanding nationwide, building on existing relationships with companies like Advance Auto Parts, MileOne Autogroup, and Hunter Engineering. “The goal is to build this public-private partnership that can really make this program available on a national scale.”

And then there’s the nonprofit’s job-training contribution: Its most recent program, Full Circle Auto Repair and Training Center, provides employment opportunities while addressing the lack of certified auto mechanics across the country.

Launched in 2015, the four-month internship for the recently or currently incarcerated provides participants with Automotive Service Excellence (ASE) classroom training and connects them with jobs upon graduation.

“The program really started out of a necessity to get our cars fixed,” Schwartz says, adding that when the organization acquired its current warehouse and auto shop in 2012, it couldn’t find enough qualified mechanics to hire. It was a challenge echoed by the local garages they had been working with.

It’s a problem mirrored across the country: There are about 750,000 auto mechanics and technicians nationwide. But with a large percentage nearing retirement and a growing need for skilled workers, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates 76,000 new employees would need to enter the industry each year to meet demands.

When Schwartz learned that the Maryland Department of Labor offered an automotive training program, it sparked an idea.

“...they leave with a job and a renewed sense of hope.”

—Janell johnson

“Why should we train guys from the ground up when we can work with returning citizens and give them opportunities?” Schwartz says. “They weren’t getting jobs when they were coming out, for the most part. Everybody needs an opportunity.”

The program works: Of the more than 130 people who have enrolled in the internship, 100 percent completed the training and were placed in jobs. So far, only one has been reincarcerated.

Finding success at the Halethorpe headquarters, the program has been expanded to a garage on Greenmount Avenue in Baltimore’s Waverly neighborhood and to Vehicles for Change’s office in Detroit. Locations in Richmond, Salisbury, and Prince George’s County are on the drawing board.

The programs, which are open to the public for services like oil changes and diagnostic tests and repairs, offer more than technical training. It’s a safe space for interns during the transition back into society that connects them with resources to help along the way.

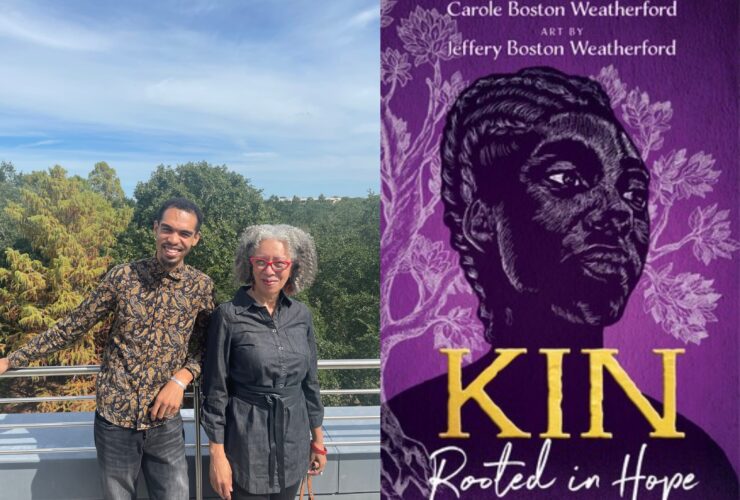

Seven years after getting the keys to her Honda Odyssey, Janell Johnson, pictured with Schwartz, is back at the organization that changed her life—this time as the senior manager of the Full Circle reentry program.

At her office in the auto shop, a photo of the current class of interns hangs beside her desk. On a piece of copy paper taped to the supply room door, Johnson has scrawled her mantra: “Wait until you see why.”

It’s part of her motivation for interns to stick it out through the challenging moments that make them want to throw in the towel, like one former intern who rode the bus two hours each way to get to the shop. When he showed up drenched from rain and especially disheartened on a stormy day, she reminded him that his hard work would pay off down the road.

After completing the program, he was hired by a local mechanic shop and returned to pay a visit. “That day that he came in here with that uniform on—oh, man,” she recalls with emotion. “I didn’t say a word. We just hugged each other.”

Johnson, who joined Vehicles for Change in early 2019 from a career in healthcare and social services, says her job often includes “being their mama bear.”

“There is an element of case management, but I’m really their accountability partner,” she explains. “We have individuals who come in here from years and years of incarceration. And while being trained to repair vehicles is all fine and dandy, they should also have access to resources. So that’s what my priority is.”

The internship also provides critical real-world experience for their resumes, and an employer who can vouch for them in a job interview.

“By the time they complete the program in four months, they leave with a job and a renewed sense of hope,” Johnson says.

It also really does come full circle: If a graduate of the training program has a job and no access to a car, Vehicles for Change will help with that, too.

Whether through the training program or by awarding cars, Schwartz says the life-changing opportunities the nonprofit provides to the community keep him motivated to show up to work each day.

“We get to see these people come back when they’re buying homes and having kids. It’s just amazing to be part of that.”