Health & Wellness

Aging Animals at The Maryland Zoo Get Special Care to Help Them Live Longer, Happier Lives

Thanks to new technology, nutrition planning, enrichment activities, and customized wellness programs, animals in zoos are living well past their life expectancies.

Like most of us past our prime, Joice has slowed down through the years and her advancing age requires some vigilance. Though she still walks uphill, her pace is not as fast as it once was. And time has taken a toll on her hip joints, first the left side, and now the right, leading to stiffness, decreased flexibility, and range-of-motion issues. To strengthen the muscles around her hips, she does physical therapy daily and gets ibuprofen when the arthritis is really acting up.

Born on May 17, 1972, in Orange Park, Florida, 52-year-old Joice, a chimpanzee, is The Maryland Zoo’s oldest living mammal. Despite being 12-plus years past her life expectancy, Joice has been an integral part of the “troop” since she first arrived in 1995.

“She has good days and bad days,” says Ellen Bronson, the zoo’s senior director of animal health, conservation, and research. “When animals are aging, the goal is to have the good days far outweigh the bad.”

On this late August afternoon, the sun is shining, the crowds keep coming, and Joice seems to be living her best life. At the sight of her keepers, Erin Dombrowskie and Ruth Collier, she places herself at the center of the high-spirited troop—among them, there’s a young chimp named Lola and her mom, Violet, and a couple of fellow adults, Raven and Louie (at 29, they’re youngsters compared to Joice) and their daughter, Bunny—all of whom vie for a spot on the fence facing the groups of visiting two-legged animals with their own broods in tow.

Today, Dombrowskie is here to do physical therapy with Joice. Holding a dowl rod, she points to an upper part of the fence where she wants Joice to reach with her left leg. Hoisting her leg high in the air, and with her right foot still grasping the fence where it meets the ground, Joice eagerly obliges, extending her long limbs like some simian ballerina.

“Good,” says Dombrowskie, as she presses her training clicker to signal that Joice is about to be rewarded with walnuts and grapes dropped in through the mesh fencing.

A few minutes later, Dombrowskie taps Joice with the dowl in the center of her chest to elicit another behavior. This time Joice thrusts her chest and hips forward. Dombrowskie clicks again and another shower of snacks ensues, as the rest of the troop reaps the perks of the PT session.

These daily stretches, designed specifically for the aging chimp, have made a visible difference.

“The last time she was under anesthesia, we noticed that when she was laying on the table, she was no longer lying flat on her back with her legs up in the air [a sign of loss of range of motion], which is what we previously saw when we had her under anesthesia,” says Bronson. “She looked pretty close to what we see in other chimps. We were amazed by that— it’s having a direct effect.”

Due to a variety of factors, including protection from predators, disease, and weather, animals in “human-managed care” (the term “captivity” is no longer used at zoos) are living longer than their wild counterparts.

“They live longer because they don’t have to work for anything,” says Erin Grimm, curator of mammals at The Maryland Zoo. And within the past decade or so, animals in zoos across the United States are living even longer lives, thanks to new technology, top-quality health care, nutrition planning, enrichment activities, and even customized wellness programs for individual animals across the entirety of their lifespan.

And, much like the ways in which the aging human populace has influenced everything from social security to health care, elderly animals are impacting the zoo’s infrastructure. There are fewer spaces for breeding, because elderly animals are living in them. And all the zoo habitats need to be adaptable to every stage of an animal’s life.

“Animals living longer, healthier, happier lives is a trend we’ve been seeing for a long time, at least as far back as the ’80s,” says Dr. John Sykes, a Bronx Zoo veterinarian, who also serves as chair of the Animal Health Committee for the Association of Zoos & Aquariums (AZA). “We are learning a lot more about how to care for them in their older years and how to keep animals happier and more comfortable for a longer period of time. That’s a great problem to have, but it does present us with new challenges. We have to think about how to care for the individuals and the populations as a whole—and sometimes those needs are synergistic and sometimes they are in conflict.”

At The Maryland Zoo, founded in 1876 and the third oldest zoological park in the United States, a significant number of the mega-fauna—that’s the term for large animals—are living well above the life expectancy for their species. Though zoo employees like to joke that the oldest living mammal is an animal specialist named Bill who has worked there since the 1960s, when it comes to the non-human mammals, there are quite a few geriatrics in their charge.

In addition to Joice, there’s Anna the African elephant, 49, and Caesar the reticulated giraffe, 18. (The median life expectancy for a female African elephant is 39.4 years, while the median age for a male giraffe is 15.1.) Other seniors include African elephants Felix and Tuffy, both born in the wild and estimated to be 41. There’s also Clyde, an elderly stork who is an estimated 36 years old (AZA lists the median life expectancy of a stork at 13.1 years), and a 64-pound spurred tortoise named Buttercup, who is estimated to be 58, thus earning her the title of the oldest animal at the zoo out of a population of some 1,300.

Although every animal—from macaws to millipedes—receives ongoing assessments, with so much of the zoo’s population living longer, geriatric care has become a big part of animal care. In that sense, it mimics human health care.

“We are trying to push the envelope on zoo medicine,” says associate veterinarian Andrea Aplasca, while standing in the zoo’s surgical suite in the on site animal hospital. “We have individualized plans for each animal. It’s a cool time in medicine, as we think about more advanced treatments or diagnostics.”

Following a trend in human medicine, veterinary medicine has become more specialized, too, allowing for more case-specific management as animals age.

“We are ready to take on almost anything, but there are board-certified specialists in zoological medicine now,” says Aplasca. “There are vets in cardiology, ophthalmology, internal medicine, surgery, similar to human fields—they’re an amazing resource.”

Zoo vets have reached out to human physicians to brainstorm on certain cases, too.

“We consult regularly with [Dr. Donna Magid,] a radiologist at Johns Hopkins,” says Bronson. “She’s worked with vets at the zoo for over three decades. Her expertise is helpful for assessing chimpanzee and other primate X-rays.”

“WE ARE BASICALLY THE JOHNS HOPKINS OF ANIMAL CARE.”

New advances include using on-site diagnostic tools such as ultrasounds and echocardiograms. For advanced diagnostics such as CT and MRI scans, the zoo partners with local medical facilities. (If an animal is small enough, it is taken off-site; if not, the scans are brought in.)

“We are basically the Johns Hopkins of animal care,” sums up Mike Evitts, the zoo’s senior director of marketing and communications.

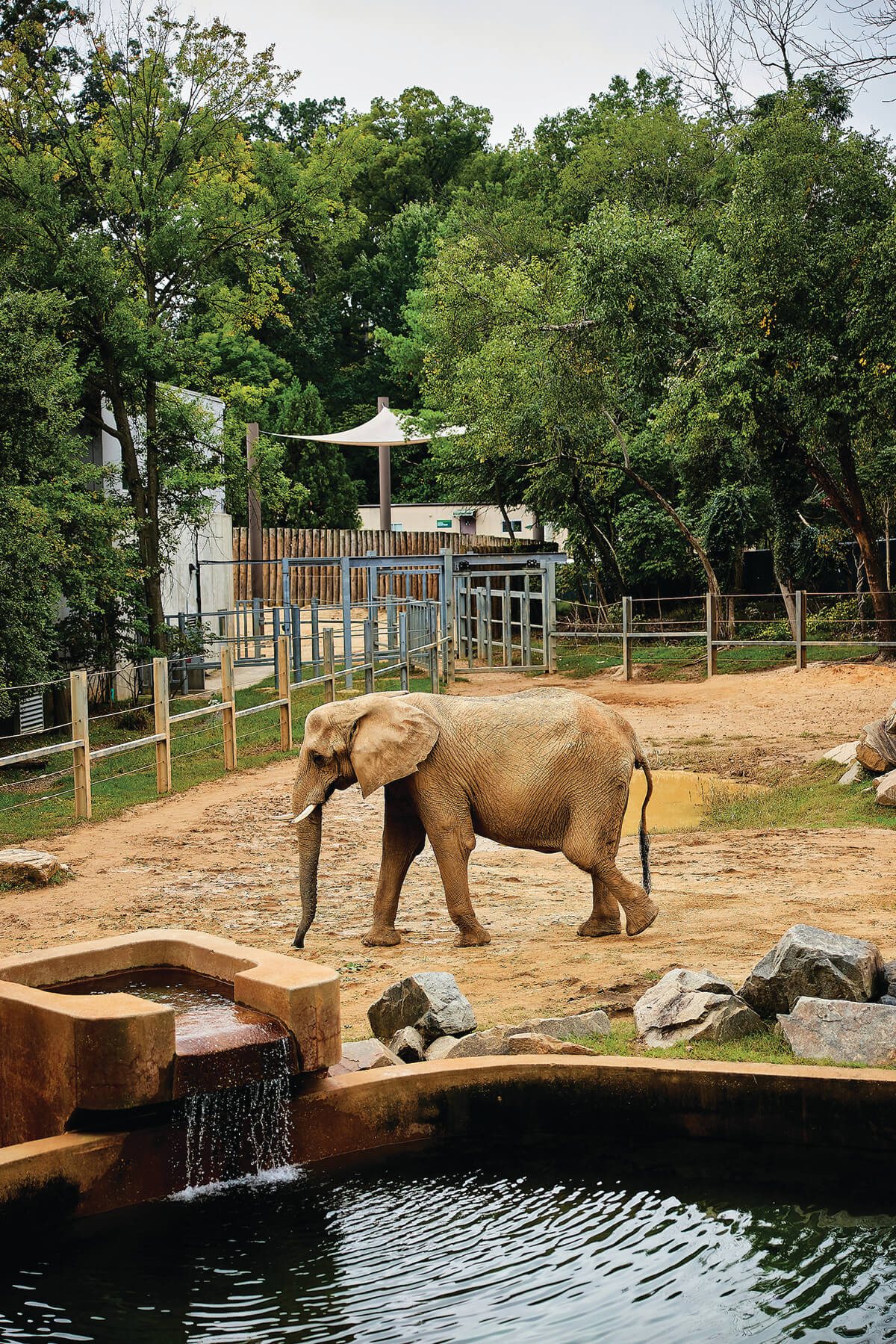

On another August day, Joey Golden, the zoo’s curator of animal behavior programs, peers out over the newly expanded elephant area known as the Savanna Overlook, where Anna the African savanna elephant is relaxing and middle-aged Tuffy shows his trainers various parts of his body, including his mouth and feet, as part of a daily check-in.

Golden’s primary job is to observe—and monitor—the animals and their interactions with their environment. Golden, along with the zoo staff, tracks the behaviors of many of the animals in the zoo’s collection, from waste output to hours of sleep to where in their habitat they hang out. Organizing his observations into graphs and heat maps, everything becomes a data point.

“I try to track everything from the temperature to the number of tickets we sell every day,” says Golden, who shares his data with animal care teams. “I look at where the grizzlies spend their time when we are closed to the public versus on a day we sell 2,000 tickets, for example. The nice thing about behavior is that it’s the common language.”

For certain animals, remote cameras operating at night give additional information. Margaret Rose-Innes, the zoo’s general curator, says that 24-hour monitoring is a relatively new tool that has proven to be very useful.

“Having all this historical data that we can then go back to and look at is so helpful. Their behavior lets us know what direction to take.”

Like other large mammals, including giraffes, Anna’s size—at last weigh-in she was 7,830 pounds—makes her prone to joint and hoof or foot issues, especially as she loses muscle density with age. As part of Anna’s care in her advancing years, with the help of video, the elephant team might look at the quality of her sleep from the night before.

“If she had a rough night and she’s stiff, or if it’s muddy and it has rained, they might scale back on activities or they might not take her up to the marsh yard,” says Golden. “They’re constantly planning.”

The video might also help inform an exercise plan. “I can pull up video of Anna walking a decade ago,” says Golden, “and then we can compare it to a video of her walking today and we can say, ‘There seems to be a bit more stiffness in that front right leg, maybe we can talk to hospital staff about adding physical therapy components.’ That baseline data is important because they allow us to see change over the course of the lifetime.”

Meanwhile, across the zoo in the giraffe area, the sleep cycle of 16-foot-tall Caesar, who has arthritis in his joints, is monitored every night.

“The keepers log what side of his body he’s resting on,” says Golden. “They log how many times he lies down or the duration of the rest. I’m able to pull up a graph that will show how much he slept on, say, July 9, 2023, and how that compares to July 9, 2024.”

To keep his joints well-lubricated, Caesar is regularly injected with anti-inflammatory medications and takes joint supplements orally to help with mobility. He gets pain medication as needed and sometimes the staff needs to alter his habitat.

“Just like people with arthritis, there are medications you can give to make him more comfortable,” says Rose-Innes. “If he’s not lying down much, do we want to give him logs to lie against so he can prop himself up? As giraffes get older, they might lie down for shorter periods of time and they might sleep standing up, so we need to change the kind of surfaces we are giving him. We are looking at installing a new soft surface inside of the giraffe pens to help with that.”

Having aging animals as part of the population presents a new set of creative challenges for the zoo staff. Exhibit A, giving injections. Not all animals submit to injections, but it’s the preferred method, the animal version of “consent.” If that’s impossible, the animal is sedated. To avoid sedation, Caesar has been trained to voluntarily come to the fence and lean in for his injections.

“He doesn’t travel around his space as much as he used to, but otherwise his mental clarity and acuity is normal,” says Amy Botke, who has worked with Caesar for 13 years and says she “loves everything about him.” “We give him toys that he enjoys and he wants to immediately bop them with his face.”

Caesar does injection training even on days he’s not getting an injection. On this day, Caesar is in fine form as he struts toward the fence, where Botke dons a bucket on her hip that’s brimming with lettuce leaves and chunks of apples. She holds a long stick with a blue rubber ball affixed to the end. She also wears a whistle.

From time to time, another trainer rubs Caesar’s hindquarter with a bristly brush in the spot where the injection will go to desensitize him from being touched in that area.

“He knows he has to keep his nose on that ball, so he has learned a hold-still behavior,” explains curator Grimm. “The whistle tells him he did what she asked him to do. He understands that every time that whistle blows, it’s paired with a snack.”

Caesar has also been assessed by a physical therapist who has recommended strength- and mobility-enhancing exercises. “Basically, he needs to learn to walk in a serpentine pattern so his hips can move across the exhibit to help him turn and use those back legs,” says Grimm.

In this case, you can teach an old giraffe new tricks. “Despite his age, he’s still willing to learn a new behavior,” Botke says. “He’s up for anything.”

For all the interventions to improve and extend life, end-of-life discussions are also a part of the planning.

“Euthanasia is one of the hardest things we have to do,” says Bronson, “but it’s also one of the best things we can do. I’m so grateful I can do that for animals, because we don’t allow animals to go through the suffering that humans have to go through at the end. Vets don’t have an easier time with that than animal owners.”

While many animals at the zoo die a natural death, knowing the right time to euthanize weighs heavily on the staff, many of whom have worked with the animals for years. And once an animal hits a certain age, the vets set up quality-of-life checks and touch base with keepers and curators.

With Anna, for example, there have been instances where she has slipped and fallen.

“If she can’t get back up, she’s in a tough position,” says Bronson of the nearly four-ton elephant. “We have teams here who can pick her back up, then we watch her carefully to see if she’s healing or has any internal stuff going on. We’re not saying we would choose to end her life, but we want to make sure that everyone is prepared for those conversations.” (Sadly, two months after we visited the zoo, Anna, who had multiple medical issues, was, in fact, euthanized after a fall.)

Bronson says caring for the zoo’s animals from beginning to end is one of the many perks of the profession.

“I’ve known so many of them as babies,” she says. “When they took their first tumbles, I patched them up. I’ve been there when they’ve had their own offspring, and then I’ve been there with them at the very end. It’s very hard, but it’s also a wonderful thing to be able to do, accompanying the animal through its entire life.”