Health & Wellness

The City That Cures

From the automatic defibrillator to the first public medical school in the United States, we celebrate the countless contributions Baltimore has made to modern medicine.

By Jane Marion and Christianna McCausland

Illustrations by Alicia Corman

hen Harford County-born John Archer graduated from the inaugural class of Philadelphia’s medical school (which later became the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine) on June 21, 1768, he became the first person in the 13 Colonies to earn a diploma from a medical college. That distinction was purely by dint of his last name—diplomas were given out in alphabetical order. Regardless, it was a red-letter day for the entire graduating class.

From the minutes written by the Board of Trustees it was declared: “This day may be considered as the Birthday of medical honors in America.”

After graduation, Archer returned home to practice in Bel Air. But back then medicine was hardly the prestigious occupation it is today. Even with his medical degree, Archer practiced what many would now consider folk medicine. Reportedly making his rounds on horses slung with saddlebags packed with medical equipment, he favored early practices like bleeding a patient to rid the body of bad spirits and treating smallbox with purging. A popular saying coined by Colonial historian William Smith was that “quacks abound like locusts in Egypt,” and it was just as likely that doctors would maim—or even murder—their patients than heal them. In fact, staying home was often considered safer than heading to the hospital.

In 1799, the Medical & Chirurgical Faculty of Maryland (now MedChi, The Maryland State Medical Society) was founded by a group of concerned physicians “to prevent the citizens [of Maryland] from risking their lives in the hands of ignorant practitioners or pretenders to the healing art.”

From these humble beginnings, The College of Medicine of Maryland (later the University of Maryland School of Medicine) was founded in 1807. It was the nation’s first public medical school and helped Baltimore establish itself as not only a medical town, but a place that would lay the foundation for the future of modern medicine. Into this burgeoning era of medical professionalism hospitals came, went, and even merged. In 1874, six Sisters of Mercy came to Baltimore to take charge of the Baltimore City Hospital health dispensary, a merger between the College of Physicians and Surgeons and the Washington Medical College. The hospital was renamed Mercy Hospital in 1909 and became the Mercy Medical Center we know today in 1988.

When The Johns Hopkins Hospital opened in 1893, it pushed the frontier further, helping to establish and improve standards for the profession and ensuring that all doctors were properly trained. William Osler, one of Johns Hopkins School of Medicine’s “Big Four” founding professors, invented Grand Rounds in 1889, giving students the opportunity to tag along with seasoned physicians as they performed their hospital rounds. And standards of care, including the idea of formal medical residency for specialty training, was instituted and is now the norm in most training hospitals.

The seed of this story was planted when we received a pitch about the history of Medstar Union Memorial’s Curtis National Hand Center, the largest hand center in the world—sending us on a quest to identify other advancements and achievements. It turns out there are more medical milestones in our city and surrounding counties than we could count.

We studied historical timeline walls at The Johns Hopkins Hospital. We visited the rare book library at MedChi and the Gibson Museum at Sheppard Pratt. We held the first surgical rubber glove at The Johns Hopkins Hospital (now embedded in plexiglass) and paged through Samuel Mudd’s dissertation on dysentery at the University of Maryland. (If your history is rusty, Mudd was the one given a life sentence for aiding John Wilkes Booth after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.) We made a field trip to the oldest continuously operating medical school classroom in the country (Davidge Hall). And debated over what should land on our list not wanting to leave anything—or anyone—out.

And while we think this list represents an impressive array of medical innovations and innovators, the reality is that we’ve just skimmed the surface.

So much of global medical practice that now seems standard was born in Baltimore. We’ve come a long way since Archer was paid by his patients in pork and cords of wood. Thanks to all the people listed below, Baltimore continues to lead the way for medical innovation in the 21st century.

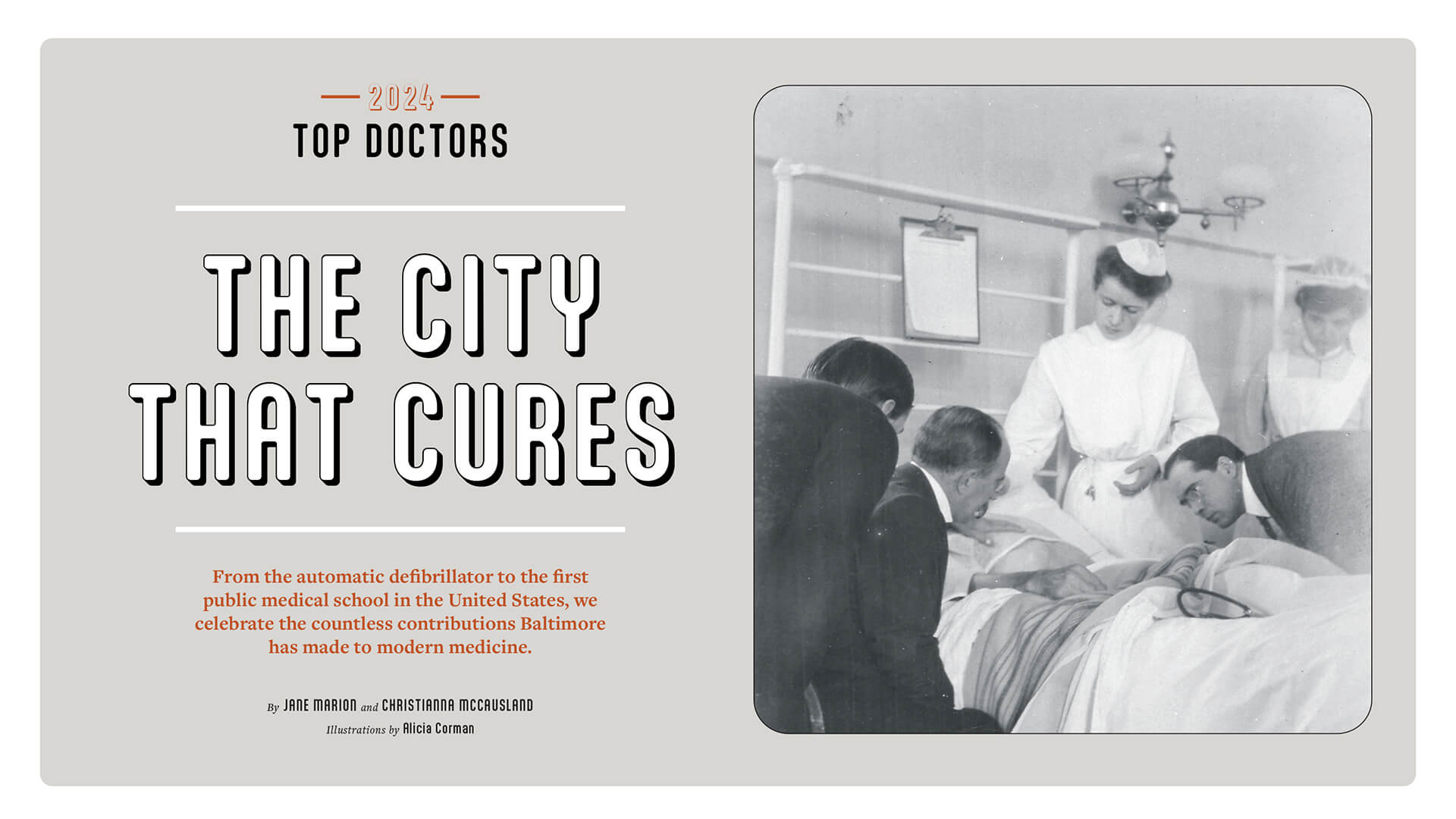

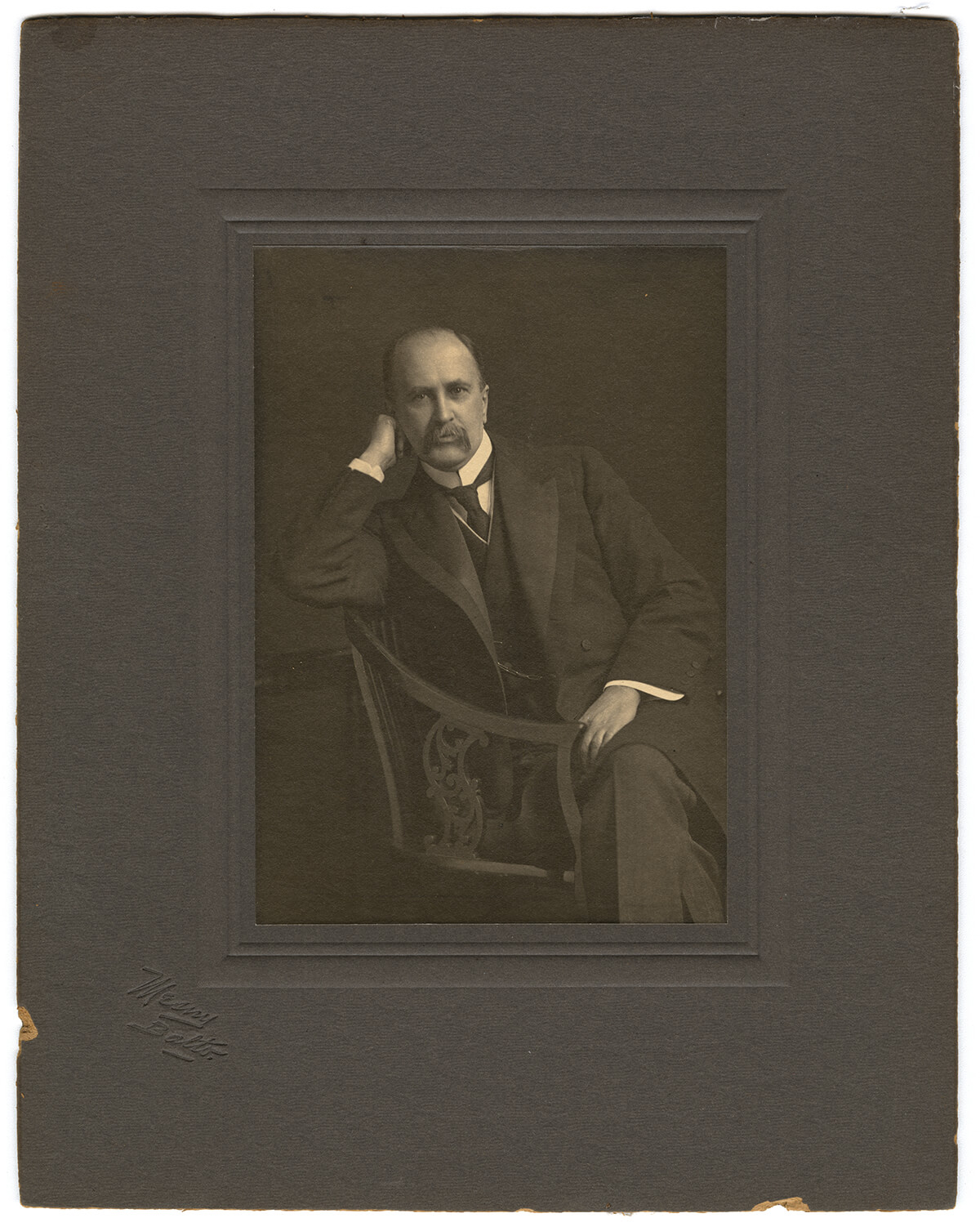

Above: JOHNS HOPKINS HOSPITAL FOUNDING PROFESSOR WILLIAM OSLER (SEATED) EXAMINES A PATIENT. —COURTESY OF THE ALAN MASON CHESNEY MEDICAL ARCHIVES OF THE JOHNS HOPKINS MEDICAL INSTITUTIONS

1. Occupational Therapy Starts Here

Sheppard Pratt is the birthplace of modern occupational therapy, a type of treatment founded by William Rush Dunton Jr. Dunton believed that participation in daily activities, including hobbies and sports, had a therapeutic effect on people struggling with mental illness. The asylum included a building that drew patients from their rooms for pastimes such as bowling, billiards, and basket-weaving, and patients were often tasked with tending to the instituition's gardens and grounds. “Occupation,” wrote Dunton in 1928, “is as necessary as food and drink.” OT is still widely used as a treatment tool.

—COURTESY OF SHEPPARD PRATT

2. The Blue Baby Operation Saves Lives

Helen Taussig is considered the founder of pediatric cardiology in 1944 and is known for her trailblazing work on “blue baby syndrome.” Along with her Hopkins colleagues, surgeon Alfred Blalock and surgical technician Vivien Thomas, Taussig developed a transformative operation to correct the congenital heart defect that prevents the heart from receiving enough oxygen, resulting in the baby turning “blue.”

Since its inception, the operation known as the Blalock-Thomas-Taussig shunt has saved countless lives and ushered in a new era of cardiac surgery that led to the advancement of open-heart surgery in adults.

Hearing-impaired from childhood, Taussig’s innovative work has been attributed to her ability to detect the rhythms of the heart through touch rather than sound. “Learn to listen with your fingers,” she once famously said.

—COURTESY OF JOHNS HOPKINS/PROVIDED BY THE KARSH ESTATE / © YOUSUF KARSH, 1975

3. In 2018, a team of nine plastic surgeons and two urologists performed the world’s first total penis and scrotum transplant at The Johns Hopkins Hospital on a veteran injured by an explosive device in Afghanistan.

4. A Treatment for Rabies

In 1897, Charles Henry Stewart became the first patient in Maryland to receive a life-saving rabies vaccine. Stewart, a Prince George’s County resident who was bitten by a rabid English setter, was treated at the City Hospital, now Mercy Medical Center, at its Pasteur clinic. Named for the French microbiologist Louis Pasteur, who created the rabies vaccine in 1885, it was only the third such clinic in the United States.

5. What Is...Sinai Hospital?

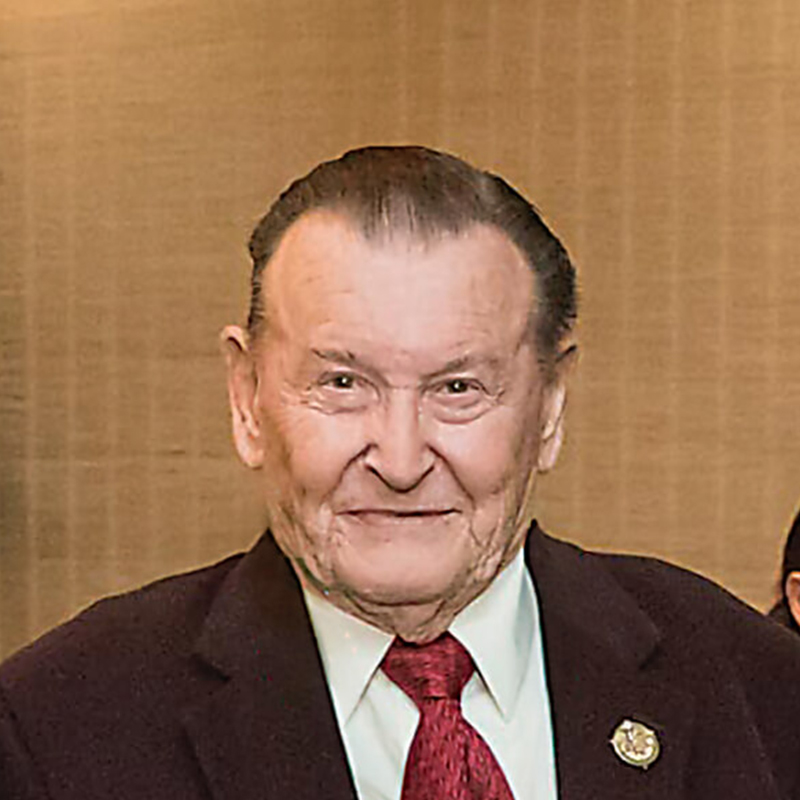

Sinai Hospital physicians Drs. Michel Mirowski and Morton Mower had an unusual idea: Create a battery-operated defibrillator so small it could be implanted in people with arrhythmia and provide a life-saving jolt whenever necessary, rather than waiting to get to an external paddle defibrillator at an emergency room. After years of innovation, Mirowski and Morton’s automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, which was about the size of a deck of cards, was implanted in a human at Johns Hopkins Hospital in 1980. The device is credited with saving many lives. In 2019, Mirowksi, Mower, and their invention appeared as clue on Jeopardy!

6. William Halsted Invents, Well, Everything

William Stewart Halsted was a founding physician at The Johns Hopkins Hospital and the first chief of surgery. He was considered one of the most influential surgeons in the U.S. Along with Department of Medicine chief William Osler, he introduced a formal multitier surgical residency program in 1889 in which students and recent graduates of the new medical school trained—and lived—at the hospital (hence, the term “residents”). At that time, they had to be unmarried. The program, whose motto was, in Halsted’s words, “See one, do one, teach one,” is the model for modern residency training. Halsted’s other accomplishments include perfecting the radical mastectomy (90 percent of breast cancer patients in the U.S. received the procedure until the 1970s). Halsted was also an anesthesia pioneer, though his work led to lifelong addiction issues after experimenting with using cocaine as an anesthetic. Additionally, he invented the idea of using surgical gloves to protect his favorite scrub nurse (and later wife). Gloves were soon serendipitously found to protect patients from infection.

—COURTESY OF THE ALAN MASON CHESNEY MEDICAL ARCHIVES OF THE JOHNS HOPKINS MEDICAL INSTITUTIONS

7. An Historical Heart Transplant

In December 2021, Bartley Griffith, MD, and Muhammad Mohiuddin, MBBS, of University of Maryland Medicine asked the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for an emergency provision to conduct a xenotransplant of a genetically modified pig’s heart into a human patient. Much to their surprise, the request was granted. In January, 57-year-old David Bennett, a Maryland resident with terminal heart disease, became the first person to successfully receive this form of transplant.

Although pig heart valves have been used in humans for years, the concept of whole-heart transplants was largely abandoned after the death in the 1980s of “Baby Fae.” The difference with this procedure is that changes could be made to the pig’s complex genome to reduce the likelihood of organ rejection. Bennett, who was severely medically compromised prior to surgery, died two months after the procedure. But for the nearly 110,000 Americans waiting for an organ transplant, his story brings hope for a new era in transplant surgery.

Planes, Trains, Automobiles, Spaceships

Dramamine was being tested as a treatment for allergies at Johns Hopkins Hospital in 1947, when a woman who had broken out into hives found that taking the antihistamine also cured her chronic motion sickness. Since then, the drug has staved off nausea for people on the go—and even been taken to outer space as a cure for space motion sickness.

Organs Take Flight

For the first time ever, an unmanned drone delivered an organ to University of Maryland Medical Center in 2019, potentially changing the speed and efficiency with which donor organs can now be dispersed. The kidney was successfully transplanted into a 44-year-old patient.

Tooting Their Own Horn

In the 1880s, the Sisters of Mercy managed to book John Philip Sousa (the Taylor Swift of his time) to play a fundraiser for their new hospital. The concert netted a whopping $20,000—over half a million in today’s dollars.

A Hospital for Everyone

In the 19th century, Baltimore’s Jewish population faced antisemitism at area hospitals. Jewish doctors were excluded from instruction and employment and Jewish patients struggled to receive equitable care. Undaunted, Baltimore’s Jewish citizens rallied to open Sinai Hospital of Baltimore in 1866 to serve anyone regardless of age, race, or gender.

8. Facing the Future

In 2012, a team of plastic, reconstructive, and maxillofacial surgeons, along with over 150 nurses and support staff, completed the world’s most comprehensive full-face transplant. Although the year prior a face transplant was completed at Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital, the transplant at R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center included the jaw, teeth, and tongue as well as all the muscles needed for the recipient to both feel and use his new face.

—COURTESY OF THE ALAN MASON CHESNEY MEDICAL ARCHIVES OF THE JOHNS HOPKINS MEDICAL INSTITUTIONS

9. The electronic defibrillator is invented by William Kouwenhoven and his team at JHU in 1957 leading to another breakthrough: modern-day CPR.

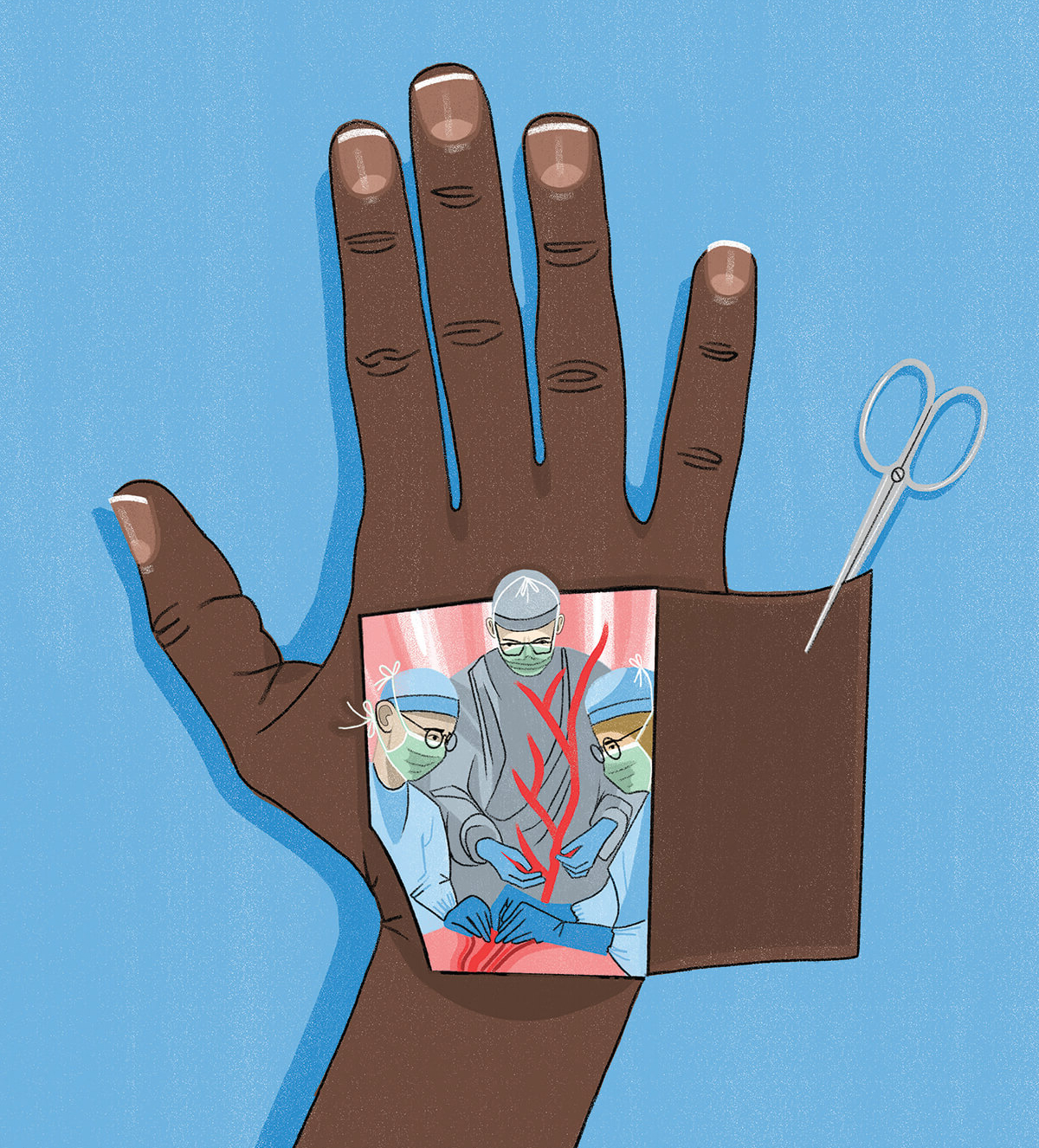

10. Landmark Hand Surgery

In 2016, the Curtis National Hand Center performed the first-of-its-kind surgery in the U.S. for radial club hand. The patient, a 7-year-old boy, was born with a shortened forearm, a bent hand, and no thumb. Surgeons used bones, a joint, a toe, and growth plates from the patient’s foot to form a functioning right arm and thumb, and to construct a full-length radius to restore the child’s forearm. Today, the boy, now a teen, is continuing to grow and has improved dexterity in his fingers and hand function that he wouldn’t otherwise have had without the surgery.

—COURTESY OF THE ALAN MASON CHESNEY MEDICAL ARCHIVES OF THE JOHNS HOPKINS MEDICAL INSTITUTIONS

11. Rounds and Residencies

In the late 19th century, Sir William Osler, the first physician-in-chief at the Johns Hopkins Department of Medicine, forever changed the course of medical training when he devised the concept of “rounds.” At that time, medical school education consisted of classes in basic science and lectures in which a physician examined patients in an amphitheater while students looked on. It was Osler who moved the mentoring to the hospital wards (which were then octagonal) where visits to the patient’s bedside with a team of physicians—known as “rounding”—became a critical component of clinical training. This allowed aspiring doctors to learn from physicians, patients—and each other. (Osler once famously said that he hoped his tombstone would read: “He brought medical students into the wards for bedside teaching.”)

On the days that Osler, known for his encyclopedic knowledge, arrived unannounced to test the residents’ understanding, the sessions were dubbed “grand rounds.” The legendary physician also instituted the idea of a medical “residency” (along with colleague William Halsted) in which staff physicians lived in the administration building of the hospital, often for many years. To this day, rounds and residencies are an essential part of medical training at teaching hospitals.

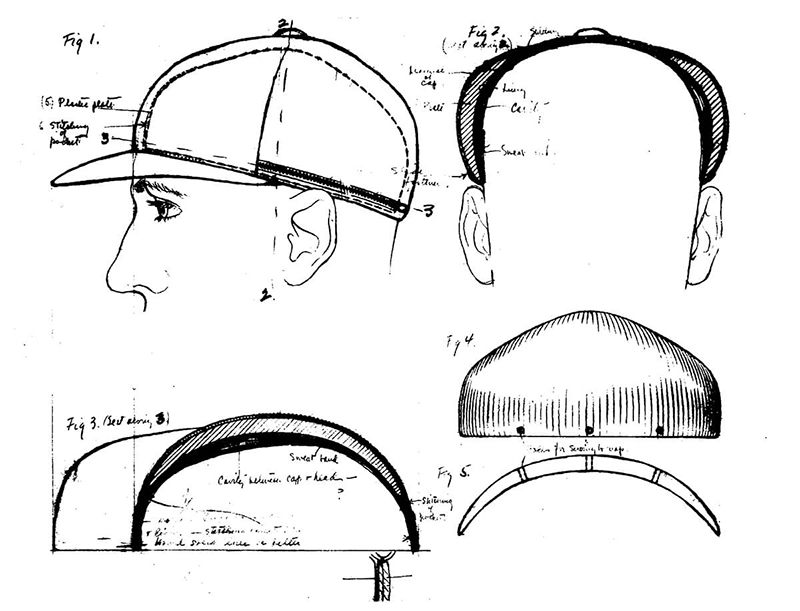

12. Safety Cap Changes Baseball

Johns Hopkins neurosurgeon (and avid baseball fan) Walter Dandy, along with orthopedic surgeon George Bennett (see below), is credited with developing a cap to protect batters from “bean balls”—a pitch thrown directly at a batter’s head. The invention—a plastic protective shield that slides into a zippered pocket of a baseball cap—was inspired by a jockey’s helmet and commissioned by Brooklyn Dodgers’ general manager Larry MacPhail, who’d witnessed a few too many injuries on the job.

It was invented in 1940 and first donned the following year by future Hall of Famers Joe Medwick and Pee Wee Reese—both of whom had suffered injuries—during Dodgers’ Spring Training in a game against the Cleveland Indians. It became the prototype for the modern baseball batter’s helmet. When the game was over, MacPhail told the media that they had just witnessed “the biggest thing that has happened to the game since night baseball.” By 1971, all players were required to wear batting helmets and the national pastime was changed forever.

—COURTESY OF THE ALAN MASON CHESNEY MEDICAL ARCHIVES OF THE JOHNS HOPKINS MEDICAL INSTITUTIONS / WALTER DANDY PAPERS, C.1941

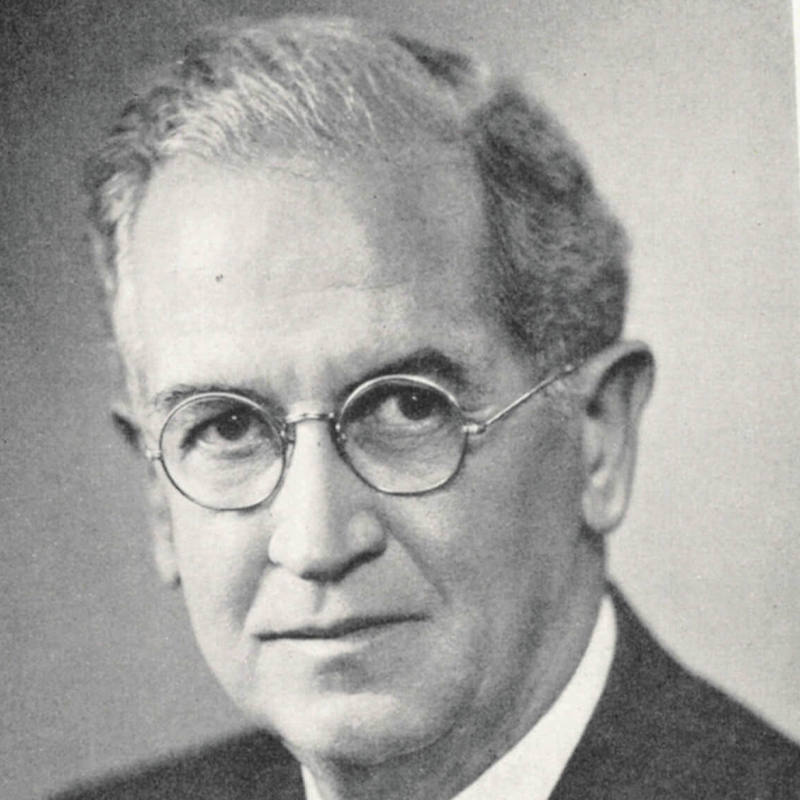

GEORGE BENNETT

If you ever suffered a shoulder injury playing baseball and received treatment, you may want to thank the memory of orthopedic pioneer George Bennett. Bennett trained at University of Maryland School of Medicine (graduating in 1908) and went to work at Johns Hopkins University. Although he had many orthopedic achievements, he is best known as the father of sports medicine, not surprising given his own love of athletics. (He played semi-pro baseball as a teen.) Bennett garnered a national reputation and treated world famous athletes including Joe DiMaggio. At the time, he was one of a very few physicians to make a correlation between sports and medicine.

JOHN SHAW BILLINGS

John Shaw Billings, a battlefield surgeon during the Civil War, made many contributions to The Johns Hopkins Hospital and medical school, including overseeing the planning and 11-year construction of the hospital and integrating teaching and research at the institution. After supervising the dismantling of dozens of military hospitals during the war, Billings became a leading expert on hospital construction in the U.S. But his most important contribution was the indexing, storage, and retrieval of information at the Office of the Surgeon General in Washington, D.C., which laid the groundwork for the National Library of Medicine. Under Billing’s directorship, it became the largest and most complete library of medical literature in the world.

RUDIGER BREITENECKER

It’s not an overstatement to say that Breitenecker changed the landscape for how rape victims are treated in Maryland. A pathologist who studied in his native Vienna, he was the assistant state medical examiner until he joined GBMC Healthcare in 1967. Breitenecker was appalled by how rape victims were treated and in 1975 he founded the Rape Care Center at GBMC, now its Sexual Assault Forensic Evidence (SAFE) Program. He ensured women did not wait hours to be seen and that they were given compassionate care. Most notably, he made rape kits more uniform and kept DNA samples from cases, believing that someday the technology would exist to analyze those samples to identify perpetrators. He was correct. The more than 2,000 samples he preserved have been used to exonerate the innocent and prosecute the guilty and the SAFE program he created is considered one of the most notable in the country.

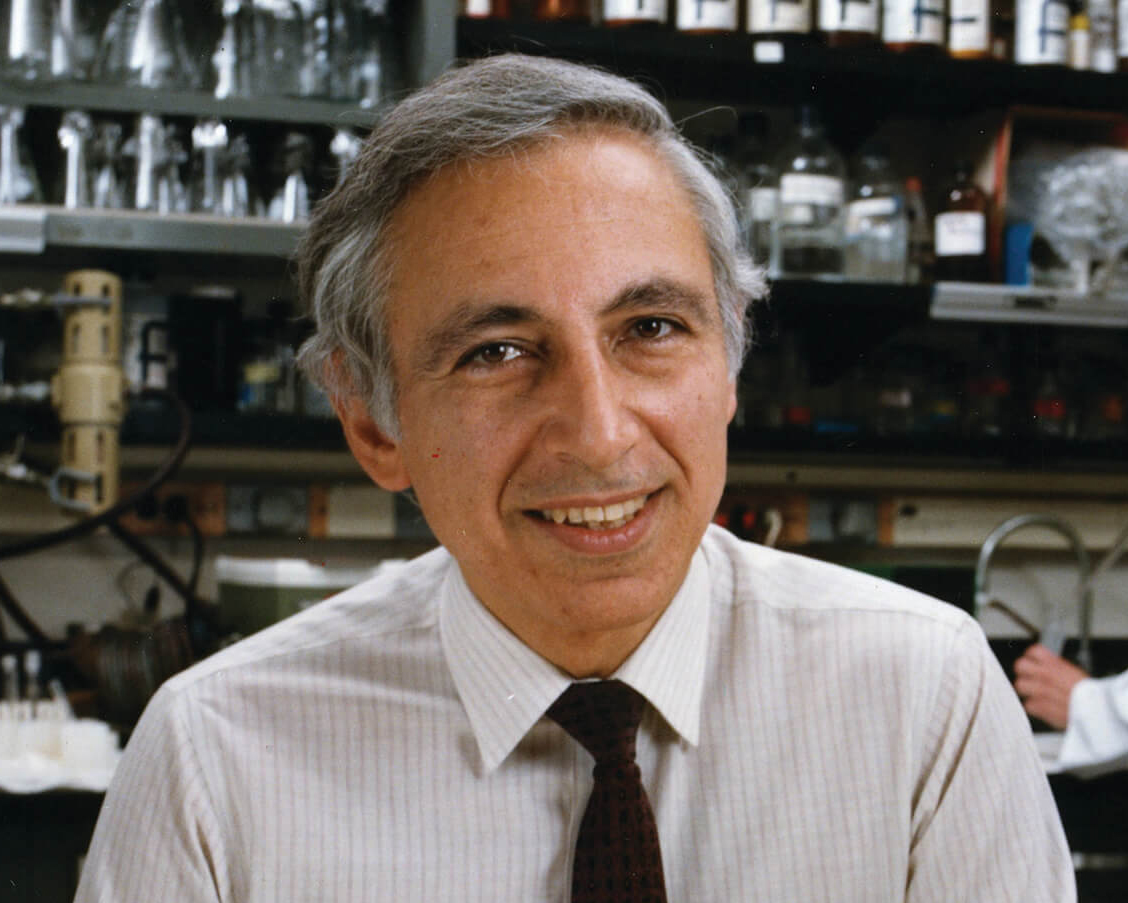

ANGELA BRODIE

Angela Brodie not only opened the door to a new way to treat breast cancer, she built the door from scratch where no one even felt a door needed to exist. The British-born scientist, who spent 37 years at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, pioneered the research that led to the creation of the first selective aromatase inhibitor, Formestane, to treat breast cancer. But when she was in the early stages of research, she struggled to get backing. Knowing her science was sound, she took matters into her own hands, using materials donated by a supply house and working with several post-doctoral students to synthesize the aromatase compound herself. “One needs to be tenacious if you think what you’re doing is going to work,” she said in a 2006 interview with Baltimore. Her research is the basis of a class of drugs that prevents the recurrence of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. While most of the cancer survivors who are alive today thanks to Brodie’s efforts would not even recognize her name, in the world of science, the physician, who died in 2017, is a star.

CAROL GREIDER

In 1984, molecular biologist Carol Greider discovered telomerase, an enzyme that is critical for the health and survival of all living organisms found at the end of chromosome strands (known as telomeres). Greider found that when telomeres are too short or too long, they contribute to disease. Her research now focuses on discovering how to keep the cells the right length to maintain chromosomes and mitigate disease. Her finding has deepened our understanding of cancer, lung, and bone marrow conditions, and other age-related diseases. Greider, now director of the Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, won the 2009 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her work.

ALAN GUTTMACHER

Alan Guttmacher was a pioneer and international leader in reproductive rights. While practicing as an ob-gyn at The Johns Hopkins Hospital, he observed a disparity in fertility rates among his patients with different socioeconomic backgrounds. One of his findings was that women who lacked access to private physicians also lacked access to contraceptive information and services. In 1933, he published the first of a controversial series of books which gave ordinary citizens access to information about pregnancy, delivery, contraception, abortion, and infertility. Guttmacher, who later served as president of Planned Parenthood, joined the birth control movement and promoted family planning, which he called, “an urgent, democratic form of medicine.”

JANET HARDY

Janet Hardy, a pediatrics professor at The Johns Hopkins Hospital, led a landmark study that provided information on teen pregnancy and medical and social issues. In 1957, Hardy help design a federal study of 60,000 expectant mothers and their children that lasted for 20 years. She served as the lead researcher for the Baltimore portion of the 12-city project, which focused on inner-city mothers and the development of their children. Hardy was the first researcher to document the dangers of rubella during pregnancy. She also showed that the children of girls younger than 18 had lower IQs and other physical and developmental issues later in life. Her studies helped establish public programs for the economically disadvantaged and inspired investigation into the effect of environment on children’s health.

WILLIAM ALEXANDER HAMMOND

Battlefield medicine has come a long way since Hammond’s day, but today’s modern military hospitals are a credit to his contributions. Briefly a professor of anatomy and physiology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Hammond became surgeon general of the U.S. Army during the Civil War. There he created a system of ambulance wagons and hospitals that significantly decreased mortality while increasing the efficiency of moving the wounded. He instituted sanitary measures, and improved record keeping, eventually founding what is today known as the National Museum of Health and Medicine. Though his tenure in Baltimore was brief, he found time to introduce microscopy to the medical school, eventually creating one of America’s largest microscopic collections.

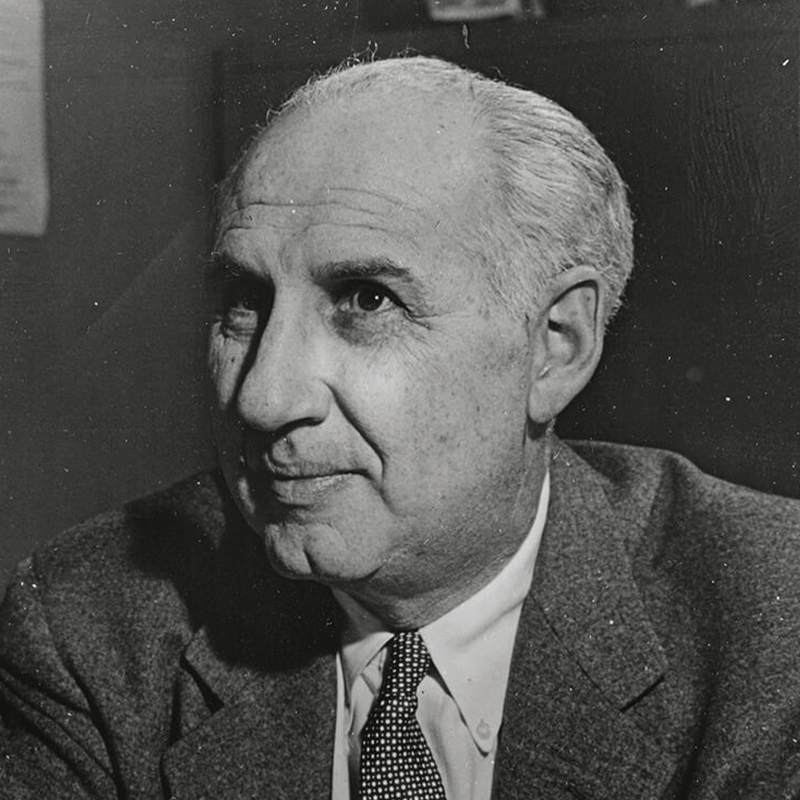

LEO KANNER

Known as “the Father of Child Psychiatry,” Leo Kanner founded the first pediatric psychiatry clinic in the United States at The Johns Hopkins Hospital’s Harriet Lane Home for Invalid Children in 1930. He also published the first English-language textbook on child psychiatry in 1935. In a landmark paper written in 1943, Kanner was the first to define and coin the phrase “infantile autism” (aka “Kanner syndrome”). He was also a devoted social activist who fought for the rights of children with autism and other disorders and is one of the co-founders of The Children’s Guild.

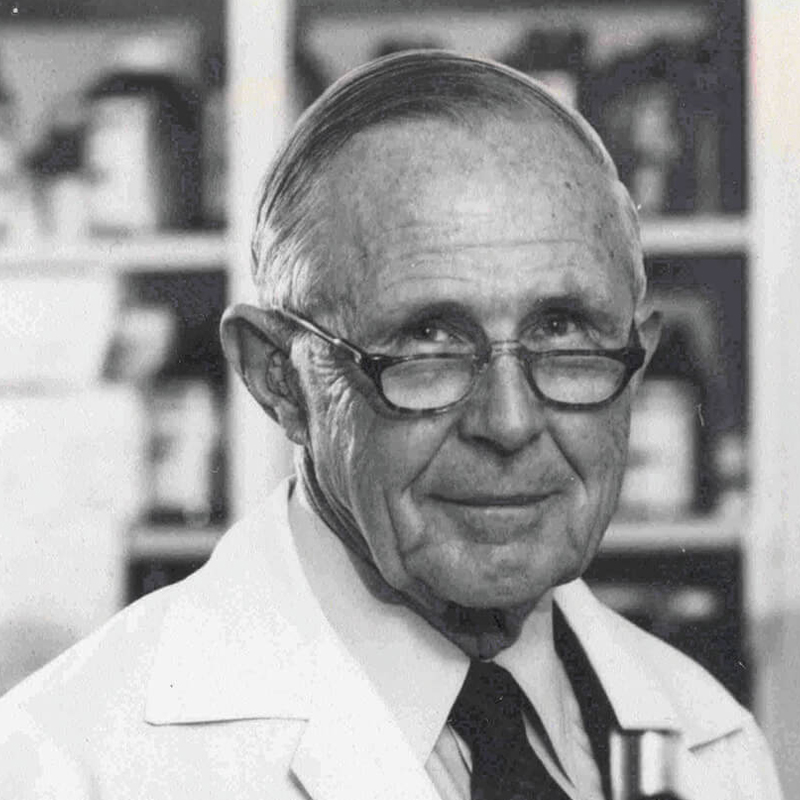

THEODORE WOODWARD

When Woodward graduated from the UM School of Medicine in 1938, he intended to open his own practice. World War II intervened. Woodward found himself studying infectious diseases like dengue fever in Bermuda. As part of the U.S. Army Typhus Commission, he helped combat major breakouts of that disease among Allied soldiers, work for which he received numerous awards, including from President Roosevelt. After the war he studied antibiotics and other treatments, including one that he and his colleagues found beneficial in curing typhoid fever. That work netted him a Nobel Prize nomination. Now considered a father of infectious disease study, Woodward founded one of the world’s first Divisions of Infectious Diseases (at UMB) and helped found the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

13. The Modern Birthing Room Is Born

In 1978, a time when women labored alone and dads were excluded from the delivery room, Alan Tapper, a founder of GBMC HealthCare’s ob-gyn department, established the first birthing room in Maryland. It was an appropriate step for a hospital that’s been called “the Baby Factory,” as it delivers more babies than any other facility in the Baltimore area (3,462 in the last fiscal year). GBMC’s birthing room allowed fathers and other loved ones in the room to offer support as a woman gave birth. Rooms had a homey décor—with wallpaper, paintings, and drapery—and medical equipment was largely out of sight. GBMC has other claims to ob-gyn fame, including the first perinatal center in Baltimore County (1985), establishment of the first Lactation Department in the Baltimore area (1989), and the first robot-assisted gynecologic surgery at a community hospital in the mid-Atlantic (2006).

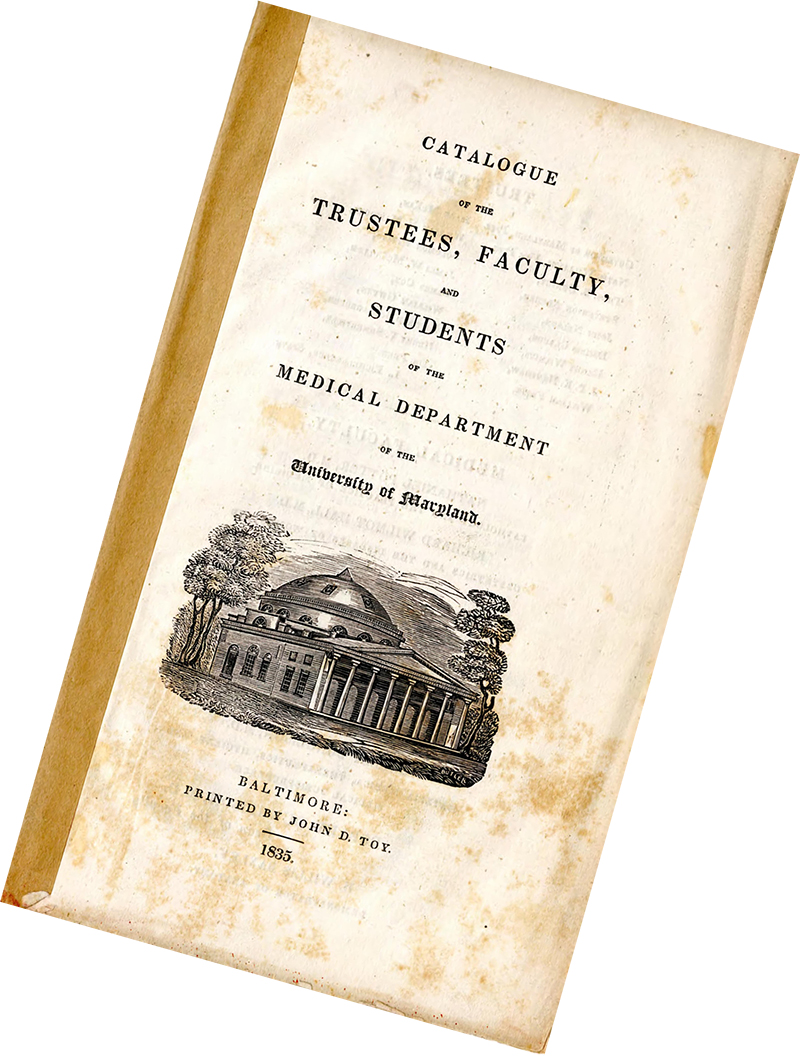

14. The University of Maryland School of Medicine launched a preventive medicine course in 1833, the first of its kind in the U.S.

—SCHOOL OF MEDICINE CATALOG, 1835. HISTORICAL COLLECTIONS, HEALTH SCIENCES AND HUMAN SERVICES LIBRARY. UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND, BALTIMORE

15. First Program for IVF in the U.S.

Georgeanna Seegar Jones was one of the country’s first reproductive endocrinologists in 1939. Her groundbreaking research on the pregnancy hormone (human chorionic gonadotropin) led to the finding that hCG was produced by the placenta, not the pituitary gland, as had been previously thought, making way for the development of the pregnancy tests that are currently on the market. Decades later, in 1981, she became one half of Hopkin’s husband-wife team that created the first program for in-vitro fertilization in the U.S. The work led to the birth of the first “testtube” baby here. Thanks to Jones, IVF flourished and gave hope to countless couples struggling with infertility.

—COURTESY OF THE ALAN MASON CHESNEY MEDICAL ARCHIVES OF THE JOHNS HOPKINS MEDICAL INSTITUTIONS

16. First Sex Reassignment Surgery in the U.S.

Way ahead of its time, The Johns Hopkins Hospital established The Gender Identity Clinic in 1966. The clinic was the first academic institution in the U.S. to perform gender reassignment surgery at a time when many hospital boards banned it. The clinic became a model for other such centers across the country, but bias and stigma led to its closure in 1979. By 2017, thanks to societal shifts leading to increased acceptance of LGBTQ+ individuals, the hospital opened the Center for Transgender and Gender Expansive Health. Since then, the center’s services have included vaginoplasty, penile construction, as well as hormone and voice therapy.

A Golden Idea

For most of the era of modern medicine, a severe accident meant almost certain death. Enter R Adams Cowley who, while serving as chief of surgery for the United States Army in Europe in the years immediately after WWII, saw how quickly European surgeons responded to trauma and the successful survival rate of their patients. Cowley, a heart surgeon and graduate of University of Maryland School of Medicine, formulated from this his theory of the “Golden Hour,” the brief span of time during which trauma patients either get to help at a specialized facility—or die. Cowley overturned the long-held belief that trauma patients should go to the nearest hospital, noting that the teams there likely lacked the necessary training. Instead, he advocated for rapid transit via helicopter to a shock trauma center.

Cowley grew his brainchild from a two-bed center to one that today sees more than 6,500 critically ill and severely injured people annually. Its patients have a 95-percent survival rate. The R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center at University of Maryland became a model for how trauma centers were designed around the world. Oh, and when he wasn’t becoming the father of trauma medicine, Cowley was “among the first to perform open-heart surgery, devised a surgical clamp named after him, and helped design a prototype pacemaker used by President Dwight D. Eisenhower,” according to his obituary in The New York Times published in 1991.

A Strong Vision

In 1944, Valley Forge Army Hospital was the epicenter of the treatment of blinding eye injuries sustained by military personnel in WWII. It was here, working with soldier patients, that Richard E. Hoover became interested in helping the blind become more independent. It was not his first experience assisting people who were blind; prior to the war, Hoover was a math and physical education teacher at the Maryland School for the Blind (MSB). For decades, white canes had been used by the blind to help them navigate obstacles but also to alert people—namely motorists—that the person holding the bright white stick was blind. While at Valley Forge, Hoover, along with MSB colleague Warren Bledsoe, devised a new way of using the conventional short, white, wooden cane for greater independence. His idea was to lengthen the cane to match the size and stride of the user and make it of a lighter weight material. He conceived of the “Hoover method” of swinging the cane back in forth to identify obstacles.

At Valley Forge, he trained others who then trained soldiers in the technique. After the war he attended medical school at Johns Hopkins, became assistant professor of ophthalmology at Johns Hopkins Hospital, and founded the Dr. Richard E. Hoover Rehabilitation Services for Low Vision and Blindness at GBMC Healthcare. He shared his teachings with MSB students and created university training programs that launched the Hoover method all over the globe..

Lending a Hand

Today we take hand surgery as a specialty for granted, but prior to WWII there was no such thing. Hand casualties in battle were treated much like any other wounded. A group of pioneering surgeons, however, saw the need for a special expertise—one that tapped into orthopedics and neurosurgery as well as plastic surgery—to treat these specific injuries. Among those surgeons was Dr. Raymond Curtis. Curtis completed a general surgery residency in Baltimore and during WWII was chief of hand service in the Army Medical Corps. Upon his discharge in 1947, he returned to Union Memorial Hospital and started a hand-focused practice. Even in the aftermath of war, the specialty was relevant, with industrial accidents and other injuries taking a great toll on patients’ finances and quality of life. Although it would not be named the Curtis National Hand Institute until 1975, by the ’60s, Curtis’ hand program had a reputation for excellence in treating injuries of the hand, wrist, arm, elbow, and shoulder.

The Curtis National Hand Center is now the largest in the world and is designated as a Level 1 Hand and Upper Extremity Trauma Center—the only such center in the U.S. Curtis began training Army surgeons during the war and true to its roots, every Army hand surgeon since 1963 has completed the hand fellowship training at Union Memorial. And Union Memorial continues to send surgeons to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center to care for injured soldiers.

17. America’s First Teaching Hospital

In 1807, the College of Medicine of Maryland opened its doors in west Baltimore, becoming the nation’s first teaching hospital. (It was re-chartered in 1812 as the University of Maryland.) Davidge Hall still stands today at Lombard and Greene Streets, the oldest continuously operating medical school building still in use in the Western Hemisphere. No surprise, it has a storied history. It was built to replicate the Pantheon in Rome and features two semi-circular theaters used for instruction including Anatomical Hall, where a plaque still stands commemorating the spot where Revolutionary War hero General LaFayette received an honorary diploma in 1824.

Its early graduates range from the famous—like Archibald “Moonlight” Graham, who was depicted in Field of Dreams—to the infamous, like Samuel Mudd who notoriously treated John Wilkes Booth after he assassinated President Lincoln. Speaking of notoriety, the school practiced the dissection of corpses and was the first school in the country to make anatomical dissection compulsory, in 1848. (That lab is now home to the alumni association offices.) While considered a normal part of anatomy instruction today, two hundred years ago dissection was thought so reprehensible that a wall was erected around the hall to keep out angry mobs that would’ve burned the building down. (In fairness, the school did sometimes obtain bodies for study through illegal means.) Since 1997, Davidge Hall has been recognized as a National Historic Landmark.

—COURTESY OF MARYLAND CENTER FOR HISTORY AND CULTURE / JULIUS ANDERSON PHOTOGRAPH COLLECTION, 1925

18. Cutting-Edge Treatment for Depression

In 2017, Sheppard Pratt conducted the largest study ever done on patients suffering from severe treatment-resistant depression. (Roughly 30 percent of those currently treated with medications for depression are drug-resistant, according to the NIH.) The results found that an implantable vagus nerve stimulation device (aka “a pacemaker for the brain”) paired with antidepressant treatment (including medication, psychotherapy, and electroconvulsive therapy) can alleviate symptoms. The study represents 10 years of research and is a new potential treatment for millions of people who do not respond solely to medication.

19. A University of Maryland professor, Dr. John Crawford, discovered germ theory in about 1790, and also determined that insects were related to human illness. Colleagues of the time dismissed his theories, but history has had the last word.

20. Understanding Lead Paint Poisoning

In 1958, J. Edmund Bradley, chief of pediatrics at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, co-wrote a paper with Samuel Bessman, Poverty, Pica, and Poisoning. In it, he reported that of a random sampling of 333 children that came through his clinic, nearly half had abnormally high levels of lead in their blood. The study collected paint samples from the homes of low-income families and found extremely high levels of lead. Through this study, Bradley correlated poor living conditions with childhood lead poisoning and called for “the cooperative effort of physicians, nurses, and social workers of municipal health and welfare departments” to combat the environmental public health issue.

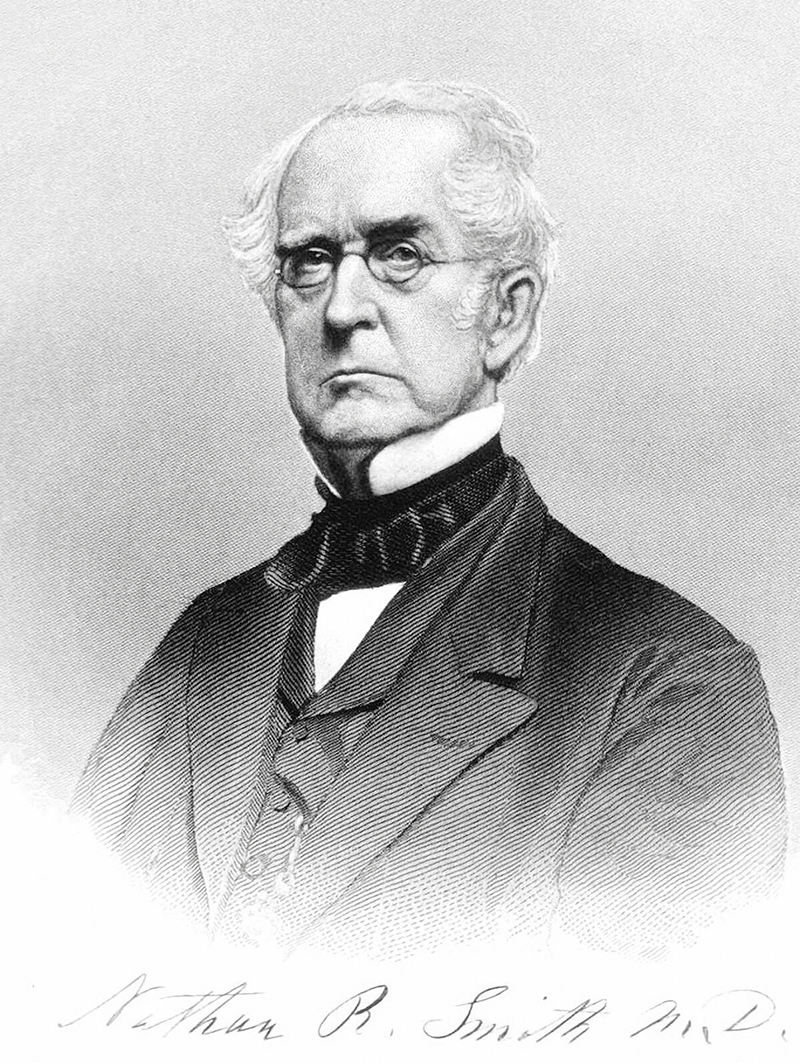

21. Better Fracture Care

Dr. Nathan Ryno Smith was a chair of surgery at UMD for 50 years beginning in 1827. He is credited with inventing a better way to set leg fractures to decrease deformity. His “anterior splint” involved suspending the limb, once made rigid, so it didn’t rest on the bed. Smith’s invention was perfected just in time to be widely used during the Civil War. As the treatment record of one patient, Theodore Pease, who took a musket ball to the right thigh at Gettysburg stated: Smith’s anterior splint continued in its use. The wounds are discharging freely and bone is practically united.

—COURTESY OF WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

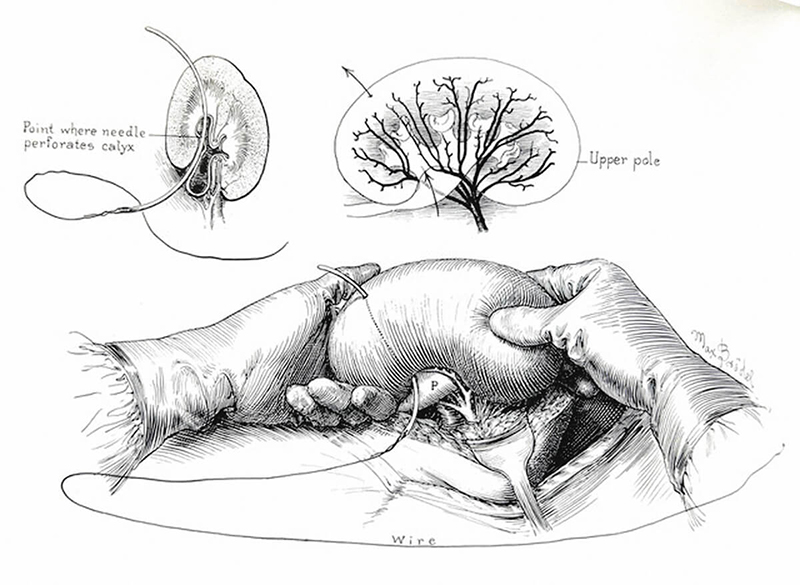

22. World’s First Medical Illustration School

Johns Hopkins’ Department of Art as Applied to Medicine trained illustrators in scientific illustration to help practitioners understand the workings of the human body. Established in 1911 under the direction of Max Brödel (and teaching continuously ever since), it was the first program of its kind in the world. Brödel is world-renowned for his life-like renderings based on observation of surgeries and autopsies. He single-handedly created the profession, which led to the founding of other programs across the country and remains pivotal to medical education today. “Leave paper and pencil alone until the mind has grasped the meaning of the object,” Brödel said. “Medical illustration is not drawing a pretty picture. It’s not just knowing the science. It’s being able to take science and the art and combine them to communicate.”

—ORIGINAL ILLUSTRATIONS FROM THE MAX BRÖDEL ARCHIVES IN THE DEPARTMENT OF ART AS APPLIED TO MEDICINE, JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MEDICINE. USED WITH PERMISSION

23. Advances In Limb Lengthening

For years, the best method of treating limb length discrepancies was to use painful external fixators, metal devices that are attached to the bones. (Amputation was another possible solution.) Sinai Hospital physicians John Herzenberg and Shawn Standard innovated a better way. The two co-developed with another physician the Precice internal limb-lengthening nail. Introduced in 2012, the nail is a metal rod with a magnetic motor inside of it. Using an external remote control, the nail slowly lengthens the limb with less pain and scarring. As one patient stated, “Before, I had a limp in my walk; now I have a spring in my step.”

24. In the 1930s, Baltimore psychiatrist Dr. Jacob Conn developed the “play interview” (i.e., the use of dolls to act out scenarios and emotions) for the treatment of phobia in children still widely used today.

25. Identifiying HIV

Dr. Robert Gallo was in an NIH lab researching tumor cell biology when, in 1975, he was the first person to identify a leukemia virus that caused cancer. This was the same era that AIDS was claiming hundreds of thousands of lives and Gallo's NIH work proved fortuitous in the fight against that disease. In 1984, Gallo and French virologist Luc Montagnier co-discovered that AIDS was caused by a virus, which they named human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). It was a breakthrough in understanding the disease. In 1996, Gallo co-founded the Institute for Human Virology at UMB and went on to develop the HIV blood test to screen for the virus and therapies that have enabled those infected with HIV to live longer.

—COURTESY OF WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

MARY ELIZABETH GARRETT

Mary Elizabeth Garrett, daughter of B & O Railroad tycoon John Work Garrett, was one of the wealthiest women in the U.S. and used her fortune to advance higher education for women. Between fundraising and personal donations, she and her friends (known as the “Friday Evening” group, inspired by their biweekly meetings at each other’s homes) raised nearly all the $500,000 needed for the opening of the financially strapped Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. But there were a few stipulations: They had to accept qualified women and the medical school should be a full graduate school whose applicants had to have a bachelor’s degree in science (which was not the norm at the time). After much consternation, the all-male founders agreed to the terms. When the school opened in 1893, three of the 18 students admitted were women—making it the first major medical school to do so. Thanks to her insistence, Garrett is sometimes called America’s greatest “coercive philanthropist.” William Osler, one of the school’s founding physicians, famously replied, “It was a pleasure to be bought.”

DORTHEA DIX

Dorothea Dix was a pioneering nurse and activist who was dedicated to improving conditions in jailhouses and asylums. Dix’s advocacy helped establish new institutions in the U.S. and Europe and led to widespread reform and changing perceptions at a time when people struggling with mental illness were housed alongside violent prisoners. After documenting the shocking conditions she observed in a Massachusetts prison in 1841, she spent four decades lobbying U.S. and Canadian legislators to establish humane asylums for the mentally ill.

Dix came to Maryland in 1852 to observe the state of affairs in its jails and almshouses, which is when she met Moses Sheppard. Although Sheppard did not take her up on her request that he fund a state asylum, she proved an enormous influence on him and his perception of treatment of the mentally ill, resulting in his ultimate decision to endow Sheppard Pratt. Dix was also instrumental in recruiting nurses for the Union army during the Civil War, appointing more than 3,000—or about 15 percent—of them. She was known for markedly improving care, even insisting that rebel soldiers get the same treatment as other soldiers. When there were shortages, she often obtained medical supplies, linens, and bedclothes through private sources and never took a single day off, working for four years straight through the war.

HORTENSE KAHN ELIASBERG

In the 1920s, rheumatic fever and tuberculosis were significant killers of children. In crowded, dirty cities like Baltimore, opportunities for respite were nil. In a world without antibiotics, ill children were often sent to convalesce somewhere with fresh air, good food, and rest in order to heal. Yet Baltimore had no such home. Enter Hortense Kahn Eliasberg. A resident of Reservoir Hill, Eliasberg graduated from Goucher College and Johns Hopkins University in an era when fewer than 40 percent of college degrees in the nation were awarded to women. While researching her thesis, Standards of Care for Convalescent Children, Eliasberg grew interested in respite care. At just 22 years old, the formidable Eliasberg got Dr. William Welch, chief physician at Johns Hopkins Hospital School of Hygiene and Public Health, onboard and, leveraging her personal connections, funded the creation of Happy Hills Convalescent Home, which opened in 1922. Notably, children were admitted regardless of their family’s ability to pay. Today the home has evolved into Mt. Washington Pediatric Hospital, a leader in pediatric care.

MARCIA CROCKER NOYES

When Noyes became the chief medical librarian of the Medical and Chirurgical Faculty of the State of Maryland (now the Maryland State Medical Society or, simply, MedChi) in 1896, it was at a time of robust growth for medicine and medical literature. Far from being a sleepy librarian stacking books, Noyes’ position was so demanding that she took up residence in the same building as the library, the “Faculty” building. According to MedChi, “At that time, librarians were expected to be on call 24/7. A physician could ring up at any time. . . . The physician would arrive shortly thereafter, consult the medical book, and hurry back to his ailing patient.”

Although not medically trained, Noyes learned under the tutelage of William Osler (of Johns Hopkins renown) and was by all accounts a dynamic leader. During her 50-year tenure she devised a new system of literature classification, served as the society’s executive secretary, and was the chief museum curator. The library collection grew from a few thousand volumes to 65,000. She also helped establish the Medical Library Association—where she was the first non-medical president—which continues to give an award in her honor. Noyes died the year of her 50th anniversary celebration, which was attended by more than 250 physicians. Her funeral was held in the Faculty building where she lived until her death and where staff and volunteers say her spirit still walks the halls to this day.

NELLIE LOUISE YOUNG

Dr. Nellie Louise Young was Maryland’s first Black female physician. After graduating from Howard University’s School of Medicine in 1930, she soon opened her obstetrics-gynecology practice above her father’s drugstore in West Baltimore. (Her father, Dr. Howard Young, was the state’s first Black pharmacist.) In 1938, Young opened a Planned Parenthood Clinic. In her 52 years of practice, she held numerous posts, including working as chief of obstetrics at Provident Hospital, serving as the women’s physician at the former Morgan State College, the girls’ physician at Frederick Douglass High (from which she had graduated in 1924, when it was known as the Colored High School), and staff physician at the Maryland Training School for Colored Girls. Young once said the “most wonderful thing in the world was to deliver a healthy baby, and to see the expression on the mother’s face and the father’s face.” She delivered thousands of babies before retiring in 1984.