Health & Wellness

Beyond Band-Aids

School nurses navigate the new normal.

O ne day, she talks to a teenager about headache triggers, diagnoses a cluster of COVID-19 cases, and quells a panic attack. The next, she troubleshoots a glitch on an insulin pump, leads a training session on asthma inhalers, and counsels a parent on the protocols of EpiPens.

For Maggie Singleton, a nurse at REACH! Partnership School, a public charter high school on the eastside of Baltimore, no two days ever look the same, and her responsibilities are constantly evolving. “School nurses no longer just apply Band-Aids and give out Tylenol,” Singleton says about her role as the main health ambassador of the urban school with roughly 700 students. Made more difficult by a global pandemic, rising rates of food allergies, and an uptick in chronic conditions like Type 1 diabetes, Singleton’s position and that of other school nurses across Baltimore involves juggling myriad demands, from reporting metrics on COVID-19 to keeping up with ever-changing medical technology.

“I used to flip through the big book, the Physicians’ Desk Reference, to figure out how to treat various conditions,” Singleton says. Now, she uses online health portals to look up symptoms and electronic medical records to enter and store patient information. “Electronic records enable me to track, say, whether the student who shows up with a tummy ache has a history of belly pain—and what that might mean,” she says.

Like many school nurses, Singleton started her career in a hospital— in her case, more than three decades ago as a surgical nurse, and then a cardiac nurse, at the University of Maryland St. Joseph’s Medical Center. She transitioned to school nursing for two reasons: She wanted a schedule matching that of her three children, and she wanted to make a difference in her community.

“I’ve never once regretted my decision to become a school nurse,” Singleton says. “It’s different and more autonomous, but it’s incredibly rewarding.”

The autonomy of school nursing took getting used to. Instead of turning to the dozens of doctors, nurses, respiratory therapists, and other specialists available in a hospital, school nurses operate largely on their own. “In a critical situation, I’m the primary decision-maker and have to rely on my training and experience in medicine,” Singleton says. “It can feel scary to have the lives of other people’s children in your hands.”

“WE SEE ALL THE ILLS OF POVERTY, AND OUR NURSES ARE JUST AS IMPORTANT AS OUR CLASSROOM TEACHERS AND VITAL TO OUR SUCCESS...”

Kelly Klug, a school nurse at Loyola Blakefield, an all-boys Jesuit school in Towson, relates. “There are slower days that involve treating mostly the sniffles, but emergencies can happen out of nowhere,” Klug says. “I’m typically the school’s first responder, which means I have to show up every day clear-headed and ready to make and act on my own decision in the event of an emergency.”

Those emergencies can range from a concussion in gym class to a seizure in the auditorium or a case of anaphylactic shock in the cafeteria, but school nurses spend much of their time helping students manage chronic conditions like asthma, food allergies, migraine headaches, and diabetes.

“When I first started working in schools, asthma was a big problem in Baltimore because of the smog and pollution from factories,” Singleton shares. “Add poverty to the mix, with students breathing in dirt and dust, and [although the pollution has improved], asthma continues, but in a less severe fashion.”

At REACH!, where Singleton works, approximately 70 percent of students live in poverty, making the school eligible for state and federal funding to pay for added support. A nurse practitioner, Vivian Soneye, spends two days a week on campus, treating students registered to receive health services and prescribing medications like birth control, allergy shots, and antibiotics (which most school nurses cannot do). James Gresham, the school’s principal, considers supports like this critical to keeping kids in the classroom. “We see all the ills of poverty, and our nurses are just as important as our classroom teachers and vital to our success,” he says.

Like asthma, food allergies remain prominent in schools, with as many as one in 13 children in the United States living with an allergy. Another health condition seen increasingly by school nurses is Type 1 diabetes. Unlike Type 2 diabetes, which can be triggered by lifestyle factors, Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease brought on by an immune reaction, typically seen during childhood or adolescence. The surge in cases, studies say, may stem from COVID-19.

“Children are often diagnosed with Type 1 at eight or nine years old, and school nurses are at the center of coordinating with both the parents and the child’s endocrinology team to help manage and stabilize the condition,” explains Courtney Pate, the director of the Home and Hospital Program at Baltimore City Public Schools, who previously worked as a school nurse. “But caring for kids with diabetes takes time and training to do effectively.” Often, it involves the near-constant scrutiny of blood glucose levels, carbohydrates, insulin doses, and exercise, with the aid of complex and ever-evolving medical device technology.

This year, Singleton helps manage 11 students, most with Type 1 diabetes. “In my entire 16 years of working [as a school nurse] at Harford Heights Elementary School, I only had one student with Type 1,” she says about her previous job. Now, however, she sees multiple teens with diabetes every day, guiding them as they adjust insulin rates and treat low or high blood sugars. “They use insulin pens and pumps and continuous glucose monitors with all kinds of bells and whistles, which I’ve learned to use, too,” Singleton says.

At Loyola Blakefield, Klug treats four students with Type 1 diabetes, monitoring their fluctuating blood sugars on her smartphone minute-by-minute and receiving alerts when levels stray too high or low. “The technology is fabulous and makes the communication seamless,” Klug says. Her goal, though, and the goal of Singleton and other school nurses in Baltimore, is to teach older kids and teens to manage the condition largely on their own.

“Students with diabetes may start out in middle school seeing me a few times every day, but we work on gaining independence throughout their time here so they can make decisions on their own as they move through and finish high school,” Klug says.

Pate takes a similar approach with public school nurses across Baltimore. “Diabetes isn’t something students will outgrow,” says Pate. “That’s why I tell our team: ‘Your primary goal is to empower children to manage their own care because their quality of life will depend on it.’”

Nudging kids to take proactive steps in managing their own medical conditions is a big part of school nursing, showing up not only in diabetes care but in practically every health-related predicament. “When a teenager comes to me and says, ‘I don’t know the name of my medication—I just know that my mom gives it to me,’ I say, ‘That’s not good,’” shares Suzanne Worthington, a pediatric gastroenterology nurse at Johns Hopkins Children’s Center, who worked for seven years as a nurse at Perry Hall Christian School, treating kids from preschool to 12th grade. “Instead of just telling kids what to do, I do my best to give them agency to start taking ownership and thinking through the consequences of their actions.”

Another way nurses prompt students to take charge of their health is by encouraging nutritious eating. At times, this can feel like an uphill battle. “Nutrition is the single greatest challenge of my job and, I would say, of our time period,” says Klug. “Big cans of sweetened iced teas, coffee drinks like Frappuccino, juices, sodas—these are all so popular among kids and add tons of sugar to their diet.” Klug considers healthy eating a key to overcoming common and chronic ailments. “If you look at many of the symptoms we see kids for—headaches, fatigue, stomach aches, digestive issues, rashes, and itchy skin—a lot of these can be traced back to what kids are eating,” she says.

Singleton agrees. At REACH!, she tallies how often nutrition comes up in conversations with students. On average, it happens twice every day. “I see students coming in with two or three bags of chips or cookies from the mini-mart, and I see the opposite: students who haven’t eaten anything all day,” Singleton says. “I ask them what kind of food they have at home and talk up the meals in the cafeteria, which serves a wholesome, nutritious breakfast and lunch to all students for free.”

Managing stress and paying attention to mental health, too, are mainstays of a healthy lifestyle—and areas that school nurses increasingly help kids and teens manage, especially after the coronavirus pandemic. According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 44 percent of high school students nationwide admitted to persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness during the pandemic. Fifty-five percent experienced emotional abuse by a parent or loved one, while 11 percent suffered physical abuse, making the pandemic an anxiety-ridden time for many teens.

At REACH!, “mental health is a huge reason students come to the clinic,” Singleton shares, echoing a frequent sentiment of school nurses at both public and private schools alike.

“Often, students come in needing an ear so they can express out loud what’s happening in their lives,” she says. “But other times, they come in crying, depressed, angry, with a wild look in their eyes, or even in the middle of a major panic attack.” More recently, she’s been called to emergencies involving “pseudo-seizures,” or mental health events that mimic a seizure and can be triggered by trauma. When this happens, or when she deems it necessary, Singleton refers students upstairs to the school’s Social Work and Wellness team, consisting of a social worker, psychologist, and drug and alcohol caseworker.

At a suburban public high school in the Baltimore area, the school nurse (who asked to remain anonymous) works closely with a social worker and five counselors, whose offices form a triangle to facilitate collaboration among the three specialties.

“Absolutely, we’re seeing more students for mental health,” the school nurse says. “Students present with somatic complaints—headaches, dizziness, shortness of breath, nausea—that are actually manifestations of depression and anxiety,” adds the school’s social worker. “It can take time and work to tease out.”

“SO MUCH OF WHAT WE DO IS ABOUT EDUCATION.”

While the pandemic is partly to blame for teens’ mental health woes, nurses and social workers at this Baltimore County school point to other reasons, too, such as the high expectations the students face. “In schools like ours, with populations of students who are dedicated and determined, who take high-level courses, and who apply to top universities, the pressure to succeed can sometimes turn into stress and create challenges,” says the social worker. Nurses and counselors help students develop coping mechanisms while working with community members— teachers, administrators, coaches, and families—to build a healthy mindset and learning environment.

“So much of what we do is about education,” says Kristin Franzen, a school nurse and director of the health center at Garrison Forest School, an independent school in Owings Mills for preschool to 12th-grade girls. “Whether it’s a student with tightness in her chest because she feels anxious or an athlete recovering from an injury, our goal is to give these kids the ability to become confident young adults who can understand their needs and take care of themselves.”

To promote health, Franzen and her team talk to their boarding students, who range from eighth to 12th grade, about the importance of self-care and sleep hygiene.

“Spending too much time on screens and social media disrupts circadian rhythms, which can lead to stress and even illness,” she says. “We know there will be nights when the girls need to cram and get stuff done, but we want them to learn during their time here how incredibly important sleep is to their overall health and wellness.” With tools like breathing exercises and mindfulness, they can also learn to self-soothe and control their emotions, which are essential life skills, Franzen adds.

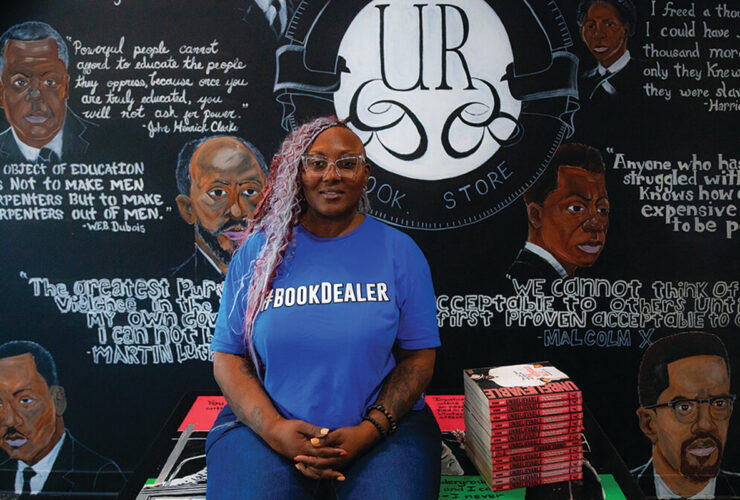

At Reach! School, nurse assistant Rhonda Somely helps with anything from minor injuries to major health issues.

AS SCHOOL NURSES TEND TO the mental and physical health of students, how do they administer self-care to themselves?

The pandemic took a toll, they say. “From the testing, contact-tracing, quarantining, reporting, calling parents, enforcing masks—it was hard to find time to breathe,” says the suburban high school nurse. Her reaction isn’t unique, given that 45 percent of school nurses surveyed from across the country said their COVID-19-related job duties negatively affected their mental health, according to the CDC.

Franzen, at Garrison Forest, compares working through COVID to her earlier job as a nurse in shock trauma. “It was like drinking from the fire hose,” she says of her experience spearheading the effort to keep the private boarding school open for much of the pandemic.

“We were dealing with the great unknown, studying the information and guidelines as soon as they became available, and making decisions in highly uncertain times,” Franzen says, describing days of donning and doffing protective gear, just like a nurse would in the hospital. “The work and concentration were intense, and I’ve barely had time to reflect because I’ve been moving full-speed ahead ever since.”

Ultimately, it was the sense of purpose that powered many nurses, including Franzen, through the frenzy. “I was really proud to be part of it, with so many people working together to stay open,” Franzen says. “I’m a helper by nature—my neighbor tells me, ‘You’re such a nurse!’” And she knows that deep down, she feels best when giving to others.

Although COVID-19-related duties persist, with school nurses continuing to test and quarantine students while reporting cases to local health departments, many nurses consider themselves back to a “new normal,” and to the usual full spectrum of taking care of their charges. Even still, across Baltimore and the entire U.S., a severe shortage of school nurses (and of nurses in general) remains, with data from the National Association of School Nurses showing that about 25 percent of schools nationwide operate without even a part-time nurse.

“School nursing is a form of public health nursing, which doesn’t pay on par with what hospitals pay, so we’re not competitive out of the gate,” explains Pate of Baltimore City Public Schools. “It’s imperative that we create a pipeline of school nurses that attracts those exceptionally caring and compassionate individuals who are passionate about public health.”

While everyone agrees that school nurses should be paid more, for many area nurses, choosing to work in a school feels like a calling with intrinsic rewards.

“I’ve had kids with cancer who get their diagnosis, get their port, go through their treatment, and then get the port removed, graduate, and go out in the world,” says Klug. “I’ve had a sixth-grader who came to me every day with bouts of anxiety, and now he’s in high school and no longer needs my help.”

These relationships and stories stick with her, as does the time Singleton made a ninth-grader grin ear to ear when she took the time to acknowledge his straight-A report card. “School nursing isn’t easy, but it’s the little things like this that go a long way.”