Health & Wellness

Top Docs 2014: Challenging Case Files

We chronicle area physicians' most challenging cases, from a devastating injury to a deadly bacteria.

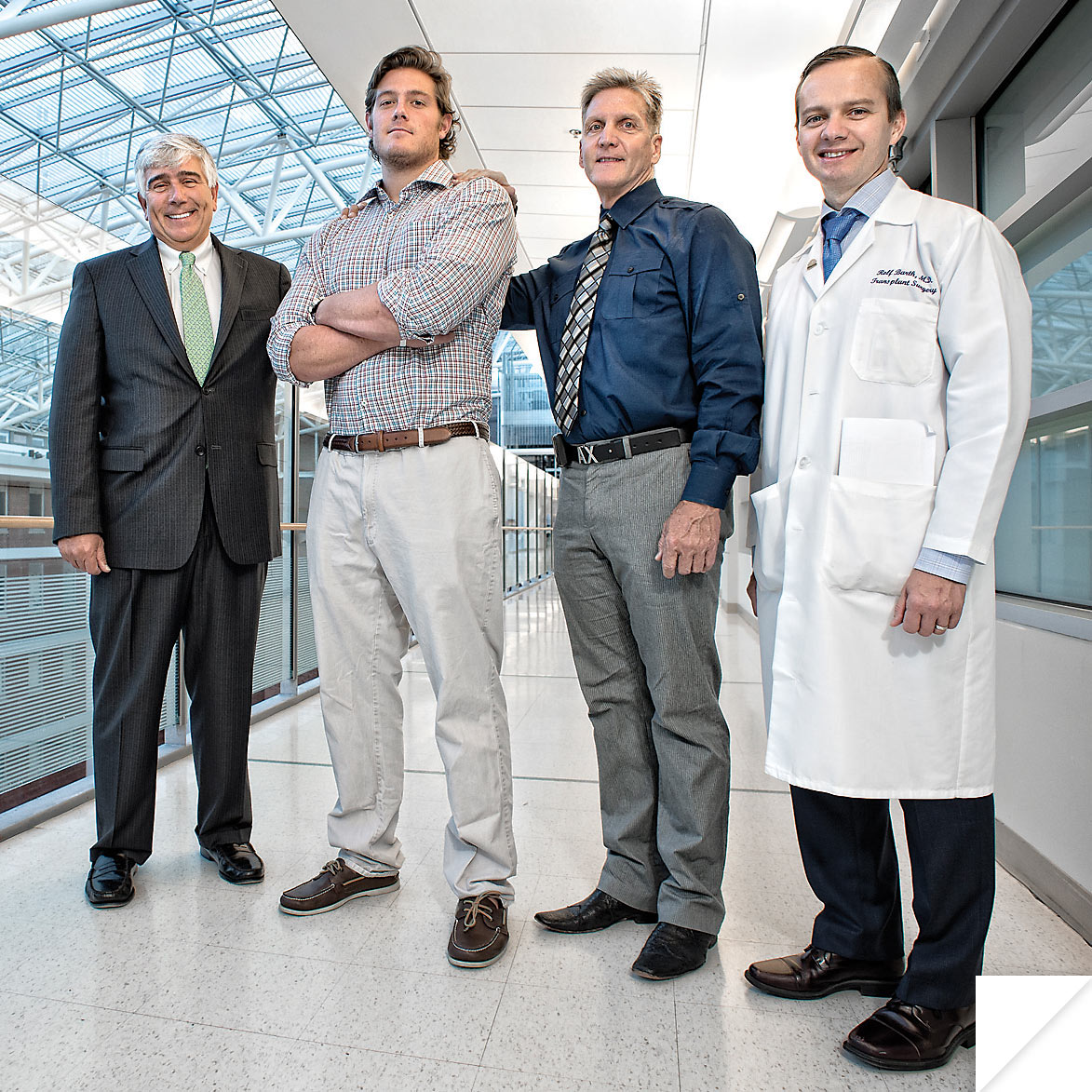

From left: Stephen Bartlett, M.D.; Gavin Class; William Hutson, M.D.; Rolf Barth, M.D.

gavin’s app

case no. 1: heat stroke

University of Maryland Medical Center: Gavin Class

It’s not uncommon to faint when you’re overdoing it in the heat— especially in football practice on a scorching hot day. So when Towson University football player Gavin Class collapsed on the practice field at Towson University in August, 2013, everyone figured it was a simple case of heat stroke. But for 20-year-old Class, then a junior, it was not so simple.

Taken to St. Joseph Medical Center, doctors saw his internal body temperature was causing multi-organ failure.

Coincidentally, only a month before, Dr. Rolf Barth, director of liver transplantation at the University of Maryland Medical Center (UMMC), had met with St. Joseph pulmonary critical-care division chief Jason Marx about a new app that alerts UMMC quickly to the very sickest patients needing more advanced care. And that app helped put the wheels in motion for Class’s transfer downtown.

“We have occasionally had referrals for heat stroke, but only when the liver is so damaged it’s non-recoverable,” says Barth. “Then transplantation is the only answer. And it was clear to our team that in Gavin’s case, the heat stroke was causing everything to fail.”

Doctors from UMMC’s shock trauma and transplant teams, including Drs. Stephen Bartlett and William Hutson, acted immediately by using a new liver support machine called MARS to buy Gavin some time while a donor could be identified for an emergency liver transplant.

“Maybe five percent of people with heat stroke will have liver failure,” says Barth. But the results for this type of transplant were incredibly poor in the past—most liver failures with heat stroke had died. “Among even those with transplantation, 75 percent died,” he says. “And the chance of dying when the patient also has kidney failure is 85 percent or higher.”

The difficult recovery course took several weeks, but all of his other organs eventually recovered, and Class is living a normal life today on a borrowed liver. He’s even back on the field supporting the Tigers (albeit from the sidelines).

So now, this burly football player has a badge of courage he could use as an ice-breaker at frat parties: “He has a nice scar he likes to show off, and

he’s not embarrassed to pull up his shirt and show you,” says Barth.

Dr. Adrian Park, chair of surgery at Anne Arundel Medical Center.

A gastric gambit

case no. 2: severe gastrointestinal reflux disease

Anne Arundel Medical Center: Patricia Reilly-Butcher

It was after weight-loss surgery in May, 2013, at a hospital in Delaware that Patricia Reilly-Butcher’s problems began. Within weeks of having a gastric-sleeve procedure that reduced her stomach size, the then-52-year-old nurse developed symptoms of severe gastrointestinal reflux disease (GERD) caused by a stricture and a recurrent hiatal hernia (HH), which is the protrusion of the stomach into the chest through a weakness in the diaphragm.

Before long, she couldn’t eat, drink, or work, and other experts she consulted offered no options, except for her local GI doctor.

“He said, ‘You have to see Dr. Adrian Park, he’s the best. This is not something you can fix three or four times, it has to be done right,’” recalls Reilly-Butcher.

So, desperate, she came to Park, chair of surgery at Anne Arundel Medical Center and a renowned laparoscopic surgeon in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease, complex hiatal hernias, and intestinal disorders.

“She came out of that weight-loss procedure with severe problems,” says Park, 53, many of whose patients are seeking a solution to previous unsuccessful treatments, what he calls “end of line” cases. “A few weeks after the bariatric surgery, besides not being able to eat or drink, she couldn’t even swallow her own saliva, was vomiting all day, and started to waste away,” says Park, who also teaches at The Johns Hopkins University.

“When you have bariatric surgery, you’re supposed to lose weight, but not that way,” says Reilly-Butcher, who went into the Delaware surgery at 320 pounds and had lost 80 by the time she saw Park. “I was vomiting my own spit.”

“This was previously a high-functioning lady,” says Park. “But she was in a desperate way, basically starving to death in front of her husband. She was losing five pounds a week six months after the bariatric surgery. And she was right on the verge of needing tube or intravenous feeding to sustain life.”

He discovered that she had a stricture at the level of the gastro-esophageal junction and a recurrent hiatal hernia. Her extreme difficulty with swallowing also led him to study the muscular function of her esophagus, which revealed that she had almost no normal peristalsis, or muscular propulsion, within her esophagus.

Laparoscopic minimally invasive surgery corrected the stricture of the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction, and Dr. Park repaired her hiatal hernia, as well as separated of the muscle layers of the bottom of her esophagus to improve her swallowing ability.

Two days into recovery, she could drink water. And within a few days, she was eating on a restricted diet. “I’m not in any pain anymore, I can eat normally, and my weight has stabilized at 225,” says Reilly-Butcher. “My goal is

to lose another 40.”

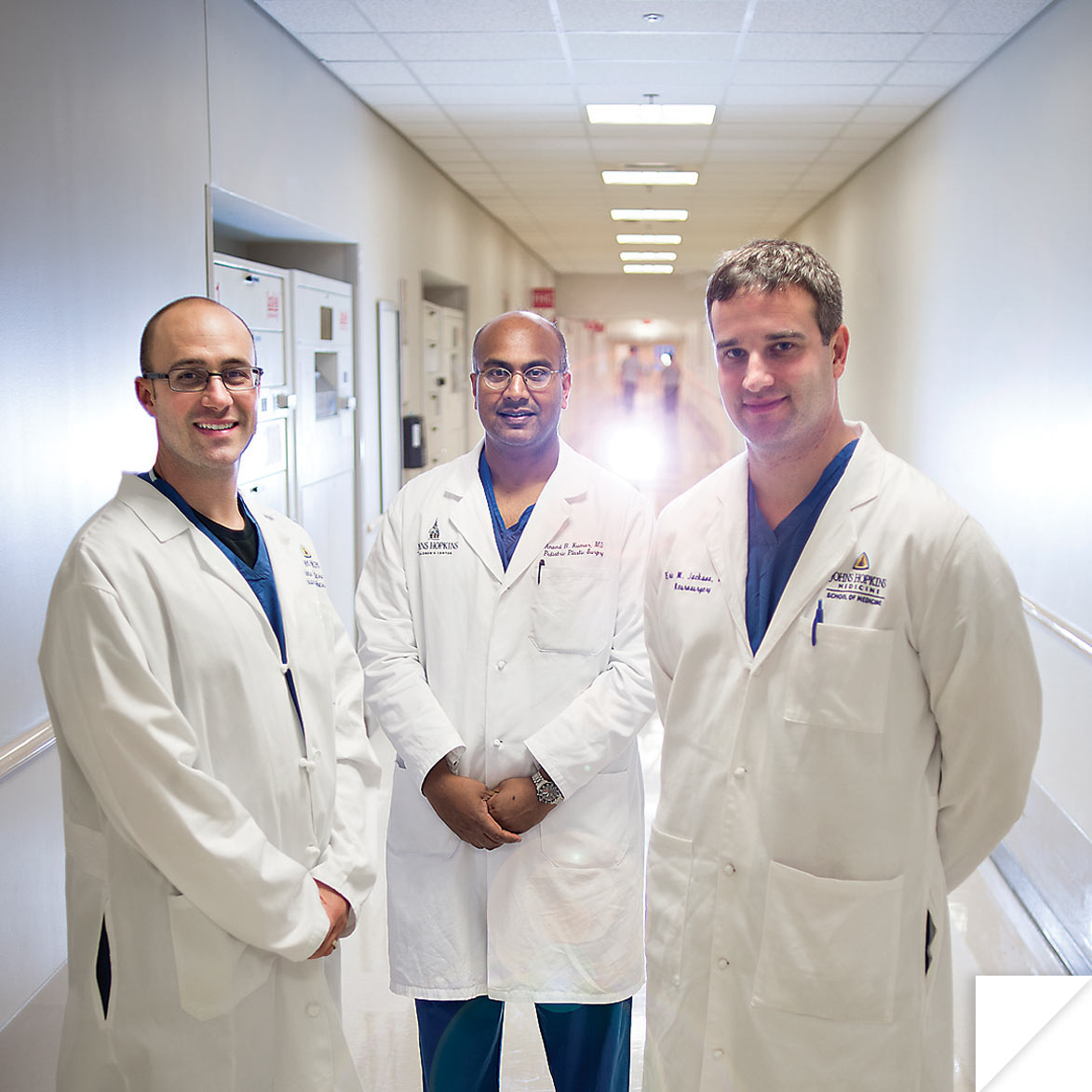

From left: Among the team in Forrest Allen’s case is Dr. Nicholas Dalesio, anesthesiology; Dr. Anand Kumar, pediatric plastic and reconstructive surgery; and Dr. Eric Jackson, pediatric neurosurgery.

A Fighting Chance for Forrest

case no. 3: skull injury

Johns Hopkins Children’s Center: Forrest Stone Allen

It was nearly four years ago that the ordeal for then-18-year-old Forrest Stone Allen and his family began. That was when the teenager suffered a devastating skull injury in a snowboarding accident that crushed his cranium from above his eyebrows to the top of his head.

And it was the beginning of a series of surgeries—not all of them successful—that eventually led him to Dr. Anand Kumar, a Johns Hopkins Children’s Center plastic and reconstructive pediatric surgeon. Kumar is a seven-year Navy veteran with experience as a surgeon at Walter Reed Army Medical Center, where he treated soldiers with traumatic injuries, expertise that is paying off for Forrest.

Forrest is benefitting from a protocol Kumar developed to treat Iraq and Afghanistan veterans with severe craniofacial injuries sustained on the battlefield.

“It was a sad case,” says Kumar. “This was a totally normal kid who had the accident after hitting a fence with no helmet. He needed a series of procedures at other hospitals that required the removal of large sections of cranial bone to treat the brain injury. Then they tried to reconstruct it with synthetic implants, including plastic and woven titanium, but none of them were successful.”

To deal with that, Kumar and his Hopkins colleagues, including Drs. Nicholas Dalesio and Eric Jackson, are employing a staged reconstruction process, approaching the job in smaller sections—first in August and again this month—using microsurgery to transfer bone from the back of the head as well as skin, tissue, and blood vessels from Forrest’s back to improve blood flow to the affected area.

“He went through three previous failed attempts. So we’re trying to turn an incredibly unfavorable thing into a success story for this kid,” says Kumar, who also does lab research looking for new ways to build cranial and facial bones from muscle stem cells.

Forrest, meanwhile, is at his Northern Virginia home with his family between procedures, winning the admiration of all around him for his determination to recover.

Writes his mother, Rae Stone, on Forrest’s family-generated blog, “You [Forrest] still tire easily and are in some discomfort, but your characteristic good

humor and determination challenge us all to keep up.”

From left: Sunjay Kaushal, M.D., Ph.D.; Susan Mendley, M.D.; Adnan Bhutta, M.D.; and Isaiah Cannon, seated.

MISSION: MRSA

case no. 4: A deadly Bacteria

University of Maryland Medical Center: Isaiah Cannon

It was a lucky thing for 15-year-old Isaiah Cannon that his older brother, John Jr., was an EMT; he was the one who noticed one day in early April that something was seriously wrong with the Edgewood teenager. The symptoms—which quickly worsened to gray coloring, shortness of breath, and inability to walk—were not just the flu. Rushed first to Upper Chesapeake Medical Center, Isaiah was then flown to the University of Maryland Medical Center (UMMC), where he suffered cardiac arrest within an hour.

“I think we suspected it was related to an infection, but didn’t know what infection right away,” says Dr. Adnan Bhutta, 45, who oversees pediatric critical care at University of Maryland Children’s Hospital. Within a day, tests showed a worst-case scenario: MRSA, or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, a drug-resistant bacteria that kills most of its victims with fast-spreading and difficult-to-treat infections.

During the hours that followed, Isaiah spiraled into multi-system organ failure and was put on a state-of-the-art machine called ECMO (short for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation). The machine, which the pediatric program had only acquired a year earlier, basically bypasses the heart and lungs, oxygenating the blood and pumping it back into the patient. In an induced coma to protect his brain, Isaiah also needed dialysis to support his kidneys and drugs to maintain his plummeting blood pressure. His muscles were showing signs of injury, and his bone marrow, which helps fight disease, was also suppressed.

“I think we all agreed if that if we didn’t use ECMO, he was likely to suffer another cardiac arrest, so we put him on it instead of waiting for him to sustain more damage to his organs,” says Bhutta. “In situations like this, where septic shock is involved, the survival rate for MRSA [pronounced “mersa”] can be extremely low, about 25 percent.”

“Survival probably would have been zero without the machine,” says Dr. Sunjay Kaushal, a pediatric cardiac surgeon who worked with Bhutta and the rest of the team.

Slowly, though, the UMMC team, which included Dr. Susan Mendly, brought Isaiah around, but it took an amazing 59 days in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) at the University of Maryland Children’s Hospital, 20 days in rehab at the University’s Rehabilitation & Orthopaedic Institute, and about $800,000 in patient expenses to get him on the mend.

Unfortunately, doctors had to amputate his lower right leg due to the lack of blood flow caused by the infection. And he still has a stent in his aorta to treat the damage.

“Right now, he just wants to be able to run again, but today was a good day,” says his mother Marcy Cannon on a Wednesday in late September. “Isaiah got his new leg today. He’s trying it out around the house. He’s been on an amazing journey.”