Health & Wellness

Something in the Water

There are a million different things you could know about saving the Chesapeake Bay. There are a thousand different things you maybe even should know. But all you really need to know is right here in our Save the Bay primer.

Once upon a time this Save the Bay business was all warm and fuzzy. Remember? It was back in the ’70s, when many of us had only just begun to suspect that humankind might be making a mess of things with Mother Nature. But, hey, we put a man on the moon, didn’t we? Making up with Mother Nature had to be easier than that.

So, flush with the tie-dyed idealism of the age, the nation went to work. We passed a Water Pollution Control Act and a Clean Air Act. We banned DDT and leaded gasoline. We made a lot of progress, actually. Somewhere in there—1976, to be

precise—the Environmental Protection Agency launched a $25 million study of the health of the Chesapeake Bay. The results that came back in 1983 were not that pretty at all. All the Bay’s vital signs were frighteningly weak. Its marshlands were disappearing.

Its underwater grasses were receding. Its birds and mammals and fish were suffering.

And the region, too, went to work. We launched the Chesapeake Bay Program (CBP), a federal-state partnership, to guide the Bay’s restoration. We convened a Chesapeake Bay Commission (CBC) to advise state legislatures on Bay issues. We established private nonprofits, such as the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF), the Chesapeake Bay Trust (CBT), and the Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay (ACB). With all those crazy acronyms in our corner, how could we go wrong? The first task seemed easy enough—everybody ponied up a little extra for a pretty Save the Bay license plate.

Ever since, it’s been an arduous, uphill slog. Along the way, our tie-dyed idealism has faded to the point where this Save the Bay business leaves many of us feeling dazed and confused as often as warm and fuzzy. Perhaps this dates to our first encounter with the word hypoxia. Or was it eutrophication that brought on the headache? Saving the Bay was never supposed to become an onerous civic chore on the order of understanding foreign trade policies and attending community association meetings.

But it’s two decades later, and here we are. Raise your hand if you’ve got all the details of this Save the Bay business down pat. Raise your hand if you’re dying to read another story about how long and hard and expensive and nigh on impossible it’s going to be.

No, really, you can raise your hands any time. Anybody?

Relax. We wouldn’t put you through that. The reason why we went out of our way these recent weeks to talk with experts and read long-winded reports and mine bottomless websites is so you wouldn’t have to. This Save the Bay primer is your road map through the algae blooms and dead zones and pfiesteria outbreaks of recent years. It bypasses all manner of detours and distractions, leading right to the straight-talking essentials: What’s wrong with the water?

Let’s dive in and find out.

Lesson 1: Yes, saving the Bay is a good idea.

In the beginning this much at least was something most everyone agreed with. But we’ve all endured a million partisan screaming matches over environmental issues since then. Amid all the acrimony over stuff like global warming and spotted owls, it’s easy to lose focus on the environmental realities of our own backyard.

So we’ll start by reviewing a few points that might otherwise seem obvious. First, the Chesapeake Bay is an ecological treasure of the first order. It’s an estuary—a place where salt and fresh water mingle—and therefore by definition supports an uncommon diversity of animal and plant life. But the Bay isn’t just any estuary. It’s the Yosemite of estuaries, the biggest and the best in the land. Plus, in case you haven’t noticed, it sure is pretty.

Second, the Chesapeake Bay is an economic marvel. Think the Port of Baltimore. Think tourism. Think waterfront property values and Eastern Shore real estate markets. Think sailboats and yachts and marinas and boatyards. Think fisheries and watermen and crabpickers and restaurants. It adds up to a whole bunch of money and a whole bunch of livelihoods.

Third, the Chesapeake Bay is who we are. Why’d they put a city here in the first place? Because of the Bay. Why’d the Brits send bombs bursting in air over Fort McHenry in 1814? Because of the Bay. Why is Fells Point so musty old maritime cool? Why do we swoon over clipper ships? Why are we goofy for steamed crabs? All because of the Bay.

Sure, saving the Bay is about namby-pamby stuff, all the cute critters and the sweet scenery. But it’s also about our economic assets and our civic sense of self. If we make a mess of it, we’re pretty much making a mess of our city, our state, our history, and our culture. So let’s get on with it, shall we?

Lesson 2: Yes, the Bay can be saved. Sort of.

When Captain John Smith sailed up the Chesapeake four centuries ago, he joked in his journals about how the fish were so abundant sailors could catch dinner by dipping a frying pan into the water. Reality check: We are never going to see that Chesapeake Bay. Our children aren’t going to see it either.

But that doesn’t mean we’re doomed from the get-go. Saying we can’t get back to John Smith’s Bay is sort of like saying the Orioles can’t win all 162 games this season. What’s wrong with aiming for the Save the Bay equivalent of a dizzyingly successful 90-win campaign? That would take the health of the Chesapeake back 50 or 75 years, to a time when it was much prettier and sturdier and more productive.

On this front, C. Ronald Franks, the secretary of Maryland’s Department of Natural Resources, is positively passionate. “If we do what we need to do,” he says, “we will leave a healthy, functioning Bay for our children. Will it be perfectly pristine? No. But it will be a heckuva lot better than it is today. And what we need to do is doable. I have no doubt about that.”

Lesson 3: No, saving the Bay isn’t going to be easy.

We could delve here into all manner of complexities involving look-it-up words from textbooks on geology and ecology. Instead, we’ll borrow a phrase recommended by Chris Conner, the director of communications for the Chesapeake Bay Program: “Just keep telling them the Bay is a little puddle at the bottom of a big hill,” he says.

No estuary in the world lies at the bottom of a metaphorical hill as imposing as the watershed that drains into the Chesapeake. We’re talking 16 million people on 64,000 square miles of land in six states.

Think baseball again. On that great day when Cal Ripken enters the Hall of Fame, perhaps you’ll make the giddy road trip up to Cooperstown, New York. It’s a long drive. You’ll need a potty break when you pull in. All that way away, you’ll still be flushing right into the Bay.

As estuaries go, this is the mother of all metaphorical hills.

“Everything we do on that land impacts the water,” says Ann Swanson, the executive director of the Chesapeake Bay Commission. “I don’t care if it’s taking your dog out to pee or idling your car or flushing your toilet. Everything has an impact.”

In such a sprawling watershed, problems roll downhill from every which way—old industrial cities, new suburban developments, vast swaths of farmland. A sprawling watershed also makes for political complications. Think about it this way: How much work would you get done on your house if the restoration job at hand required building permits from 26 federal agencies, six state governments, the nation’s capital, and some 1,700 different county boards and city councils?

One more complication worth noting: This Bay is also unusual in the metaphorical puddle department. It’s more shallow in more places than most estuaries. Its mouth is narrower, more restricted. This means water doesn’t flush into the ocean as easily or as quickly as in other estuaries. So saving this Bay is kind of like trying to do today’s dishes when you can’t get yesterday’s dirty water out of the sink. Yuck.

Lesson 4: And yet, saving the Bay isn’t all

that complicated.

Yes, this sounds like a contradiction. Bear with us. When you scan the newspapers day after day, the Bay’s problems roll out onto your breakfast table in wave after wave of scary headlines. The crab harvest is low! Underwater grasses are struggling! The “dead zone” is expanding! The marshes are receding! The bacteria are advancing! The rockfish carry Mycobacterium marinum!

None of this is good news. All of it bears careful monitoring. But the Save the Bay news cycle can be deceptive. It can leave us feeling desperate and hopeless over the sheer number and daunting variety of problems that need solving.

Now imagine a similar run of day-by-day headlines devoted to the next time your baby daughter catches a cold. Her nose is running! Her throat is sore! Her head throbs! Her muscles ache! She can’t even stay awake! Sounds awful, but it’s still just a cold.

Of course, what ails the Bay is much more serious than a cold. But our point is that it isn’t a slew of discrete ailments. It’s one big ailment with a bunch of interrelated symptoms. Why can’t the underwater grasses thrive? Why aren’t the crabs rebounding? Why won’t that dead zone just go away already?

Like the headline says, it’s something in the water.

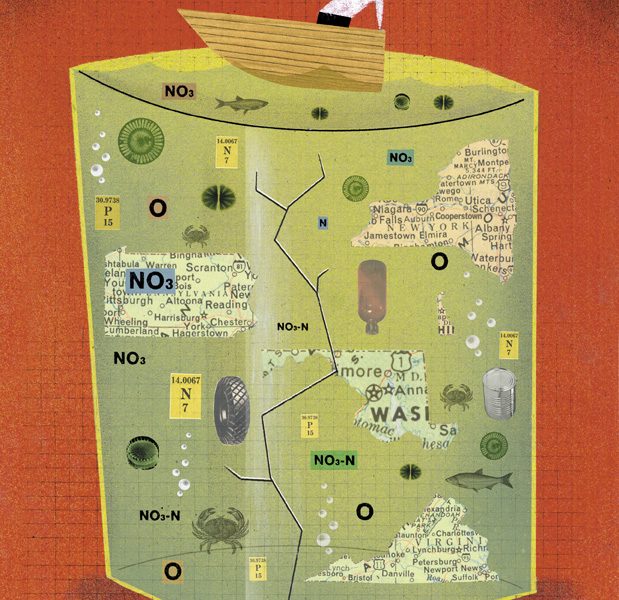

That something is nutrients—namely, nitrogen and phosphorous. Nutrients in the Bay are sort of like alcohol in humans. In moderation they’re fine, even healthy. In excess, it’s another story altogether. And thanks to us humans, the Bay is on a godawful nutrient bender.

The poop we flush, the fertilizer we use, the exhaust from our cars, it’s all chock full of nutrients. Plus, we humans have a nasty habit of disrupting the natural flow of things between the Bay and its metaphorical hill. Consider rainwater. When rain falls in a forest, trees suck nutrients out of the water before it gets to the Bay. But when we urbanites and suburbanites divert rainwater along rooftops and down driveways and into storm sewers without letting it brush up against so much as a single blade of grass, that rainwater is chock full of nutrients. Only now it’s called “urban runoff.”

And so the Bay is thick with nutrients. This is where things get weird. As we all know, nutrients boost growth—that’s why poop makes such good fertilizer, right? Well, when the Bay’s on a nutrient bender, its growth patterns go haywire. It’s like the back story to the old Godzilla movies, with nitrogen and phosphorous in the roles of the atom bomb and radiation.

Algae growth, especially, goes ballistic. When this slimy stuff blooms in vast colonies in the Bay and its tributaries, it darkens the color of the water and blocks sunlight that would normally penetrate deep below the surface. The living things of the Bay and its rivers badly need this sunlight. Eventually, all that algae dies and starts decomposing. An ecology geek could spend hours explaining to you why it is that the decomposition process sucks up oxygen, but all you need to know is that it’s true: Too much decomposition means not enough oxygen. The living things of the Bay and its rivers badly need this oxygen.

There you have it, all you need to know about hypoxia and eutrophication. It’s not a pretty picture. When the Bay’s on a nutrient bender, it’s basically shutting itself off in a dark place and choking itself to death. Gruesome, to be sure, but there’s also something oddly reassuring about it. When you dig down to the essentials, it becomes clear that right now this Save the Bay business is really about only one big thing.

Better yet, we know exactly how to deal with that thing.

Lesson 5: Despite all that, we still haven’t saved the Bay.

It’s a hard job, remember? Our army of acronyms can quite rightly cite lengthy lists of positive accomplishments. Many of our politicians can quite rightly say they’ve taken significant Save the Bay strides. But the bottom line is this: In 1985, about 340 million pounds of nitrogen and phosphorous rolled down our metaphorical hill into the Bay; in 2002, that nutrient load was about 285 million pounds.

That’s a small dip. It doesn’t get us even within sniffing distance of the Chesapeake Bay Program’s long-term goal of 175 million pounds a year. It’s worth noting that this smidgen of progress came during a stretch when human pressures on the Bay were intensifying, thanks to population growth, sprawling residential development, and rising agricultural productivity. If we’d done nothing these last two decades, the Bay would be in deeper trouble than it is today.

Still, not even the most cockeyed optimist would say we’ve made enough progress. In fact, two recent books—Chesapeake Bay Blues, by Howard Ernst, and a newly updated edition of Turning the Tide, by Tom Horton—offer assessments of the pace of restoration that border on blistering. Both books are pretty heavy on the doom and gloom, but that’s okay. There’s a horse-race aspect to this Save the Bay business, and right about now is probably a good time for smart and impatient folks like Ernst and Horton to apply a little whip.

What’s the hurry? That question brings us to another of those words ecologists toss around—resiliency. It refers to the ability of a natural system like the Bay to bounce back from natural setbacks like drought and deluge and hurricane. Because it’s on a nutrient bender, the Bay has poor resiliency. That makes it vulnerable, kind of like a person with a weakened immune system.

Until its resiliency improves, there’s a constant risk the Bay will suffer irreparable damage if and when Mother Nature gets out of hand. What kind of damage? It could be anything, really—the total crash of an already iffy crab population, say, or a major advance by a destructive creature like our old friend pfiesteria. How much risk? Sorry, no way to measure that. All we know is that every day of dawdling on this Save the Bay business is an extra day of potential catastrophe.

That’s one reason we need to make real progress real soon. But it’s not the only reason. The Bay has long had the dubious distinction of being on the federal government’s list of “impaired waters.” This doesn’t much matter right this second, but it might matter a great deal if the Bay remains officially “impaired” when the year 2011 dawns.

Under current law, the feds would then have the power to impose a Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) of nutrients for the Bay. The feds aren’t exactly renowned in such situations for their sympathetic and flexible way of dealing with us locals—they pretty much just dictate what you need to do and when and how you need to do it. So mandatory TMDLs could bring down a world of regulatory hurt on Maryland and the other watershed states.

Hard as it might be to Save the Bay by 2010, there’s a good chance it’ll be significantly easier and cheaper than the alternative.

Lesson 6: Here’s what we need to do to Save the Bay.

The Bay gets its excess nutrients from many different sources, but we don’t need to detail every last one of them. Some are too minor to merit our attention. Others lie outside our control. It’s not like we Marylanders can just vote tomorrow to outlaw the air pollution that wafts in from industrial sites in the Ohio Valley and drops nutrients into the Bay.

But three big nutrient sources are within our control. “Point source” pollution—nowadays, that’s mostly human wastewater—delivers about 20 percent of the Bay’s nutrient load. Agricultural pollution delivers about 40 percent. And the aforementioned urban runoff delivers a bit more than 10 percent.

David Bancroft, the executive director of the Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay has a nifty way of shaking these numbers up and looking at what they mean from a different angle. If we do a good job on human wastewater, he says, that’ll get us about 30 percent of the way to the 2010 goals. If we also do a good job on agriculture, that’ll get us another 60 percent of the way.

Think about that. Just two fixes could get us nearly all of the way there. We’d be within a few tweaks and a little luck of hitting the nutrient magic number. The way the Alliance sees it, that might give us the luxury of putting that urban runoff business on the back burner for now. That’s a relief, considering what an expensive undertaking a serious runoff fix would be.

Still more good news: Maryland has already put one of our two fixes into motion. That’s what the new “flush tax” is all about. It passed at the tail end of this year’s legislative session in Annapolis, a sweet note of bipartisan accomplishment amid the deafening din of deadlock over slots and taxes. Officially dubbed the “user fee for wastewater treatment facilities,” it amounts to $30 a year per household, which will go into a kitty to finance state-of-the-art nutrient-removal upgrades at the state’s wastewater treatment plants.

By Save the Bay standards, this is an astounding development. Maybe if we weren’t all so hyped up one way or the other about slots, it would have gotten more of the attention it deserves. Writing in an op-ed piece for the Sun, Chesapeake Bay Foundation President William C. Baker was downright euphoric. “Historic,” he called it. And, “The most important legislation for the Chesapeake Bay in many years.” Remember that when you feel like grumbling about having to shell out an extra $2.50 a month.

So all of a sudden, there’s only one of the big three fixes left on our list: agriculture. Unfortunately, this one’s a doozy.

Success here means getting all of Maryland’s farms to operate according to a series of “best management practices,” or BMPs. These are things like preparing nutrient management plans to avoid overfertilizing fields, planting post-harvest cover crops to suck up leftover nitrogen from the soil, and establishing forested buffer areas along all streams and rivers near farms.

There are two obvious ways to approach this. One is to pass a law that forces all the BMPs down the farmers’ throats. This has about as much chance of passing the legislature and winning the Governor’s approval as a blue crab does of winning the Maryland lottery. Plus, the cost and aggravation involved would probably put a lot of farms out of business. And it might tick the farmers off; actually, it’d probably drive them to the verge of armed rebellion.

It’s true that Maryland passed a law a few years back requiring farmers to prepare nutrient management plans, but the farmers are still bitter about that. When it comes to all the other BMPs, the carrot is likely to be a much preferable and more realistic option than the stick.

Consider one example, cover crops. Maryland already has a program that offsets costs incurred by farmers who plant them. It’s very popular with farmers. It’s very important for the Bay. But it’s also been woefully underfunded.

The flush tax law is going to help here; it sets aside about $5 million a year for cover crops out of fees paid by septic-system households. Russell Brinsfield, director of the Maryland Center for Agro-Ecology, guesstimates this will get us to about 200,000 acres of cover crops. Problem is, we’ll probably need to get up around 600,000 acres in order to hit our nutrient magic number.

Remember, there are a whole bunch of other BMPs we’ve got to deal with in farmer-friendly ways. And there’s a separate set of agricultural issues we need to deal with, related to chicken farms and chicken poop. They’re all going to be like this cover crop thing—a little too complicated and a little too expensive, especially with lawmakers staring down a $900 million hole in the state budget while struggling to fund our schools and fight our crime and protect our homeland security.

In May, the Maryland Department of Natural Resources outlined its so-called “tributary strategies” to reach the state’s Save the Bay goals by 2010. In addition to agricultural issues, it delves into urban runoff and septic systems and even a bit of air pollution. At its bottom line is a cover-your-eyes price tag of $13.6 billion. That works out to an annual rate roughly triple what we’re spending on the Bay now. Details of the plan will be hammered out by year’s end in a series of public meetings around the state. In the meantime, a newly established Chesapeake Bay Financing Commission will begin pushing for a significant influx of federal dollars.

Lesson 7: Saving the Bay isn’t a one-time

rescue mission.

Time for another reality check. This Save the Bay business is never going to go away.

In the first place, the Bay’s recovery from its nutrient bender will take time. All the Bay’s living things won’t magically bounce back the instant that nutrient load dips down to 175 million pounds a year. It’d be best if we helped the recovery along by planting underwater grasses, creating rich habitat, restoring marshlands, and opening up fish passages. We’re doing some of that already, of course, but we might want to do more.

We’ll want to worry about oysters as well. Now that the Bay’s native oysters have been devastated by disease, scientists are trying to figure out whether we can help them come back or whether we should introduce a disease-resistant Asian variety of oyster. Oysters are useful critters—as “filter feeders,” they have the nifty habit of filtering nutrients from the water naturally.

In the second place, there’s the matter of us humans and our demographic trends. The watershed’s population is 16 million today. It’s supposed to hit 18 million by 2020. It’ll hit 20 million soon after that. That’s more poop, more car exhaust, more urban runoff, more of all the things that fuel the Bay’s nutrient bender. Even if we do get down to our nutrient magic number, we’ll need to fight like hell in the decades ahead just to keep it there.

In a way, though, all these questions are secondary. What we’ve done here is lay out a case for the primary thing—the big and essential job that absolutely needs doing to give the Bay a fair shot at a reasonably healthy future.

Of course, even this isn’t something we Marylanders can accomplish all on our own. The Bay is a little puddle at the bottom of a big hill, remember? All those other watershed states might well turn out to be total slackers who go right on with their old ways of dumping nutrients into the Bay.

But if we do our fair share, at least we’ll be the ones standing on the moral high ground. It won’t be our fault that the Bay is still thick with nutrients. And who knows? Maybe by doing our fair share as Marylanders we could accomplish something grander and more important.

“If we want the rest of the region and the rest of the nation to view the Chesapeake Bay as a national treasure,” David Bancroft says, “then one of the first things that needs to happen is we need to treat it that way ourselves. We need to be the first ones there. We need to show the way.”

So let’s go on with it, shall we?