Health & Wellness

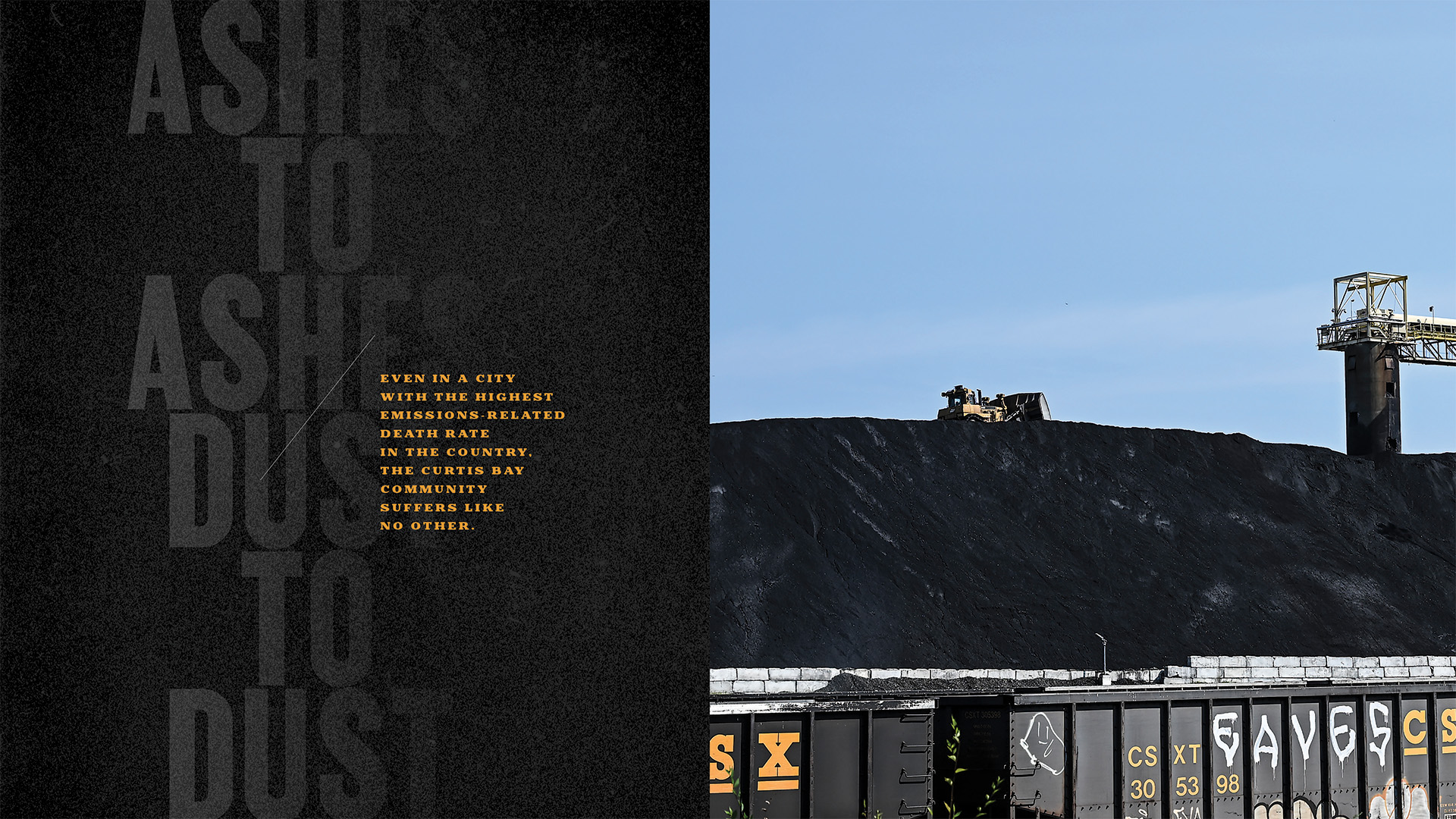

Ashes to Ashes, Dust to Dust

Even in a city with the highest emissions-related death rate in the country, the Curtis Bay Community suffers like no other.

By Ron Cassie

Photography by J.M. Giordano

NGIE SHANEYFELT HAD NEVER been more scared as a mother. She was on the last day of a COVID-19 home quarantine on the morning of Dec. 30, 2021, starting to feel better, straightening the house and looking after her twin girls, when she suddenly felt their end-unit rowhome wobble.

“The only way to describe it is this ‘pressure’ hit the house and this huge sound, like a sonic boom, followed,” she says, standing on her front porch nearly three years later with her husband, Patrick, and the now-11-year-old girls. “I’m in the middle of my living room and looking around and I’m thinking, okay, the lights are still on. My windows are intact. This was not fireworks or a car backfiring. No one is shooting outside. What the heck is this? My one daughter is on the couch, and she turns towards me for direction, ‘What do we do?’

“And then I turn to my other daughter, who has sensory issues. She has mentally checked out. Completely checked out. I gently tap her chin four or five times and tell her, ‘Ariel is okay, Ariel is okay.’ It’s frightening to look into your child’s eyes and they’re not there and you don’t know what just happened.”

A girl watching a Curtis Bay community coal protest march past her rowhome this summer.

A massive methane explosion at the CSX coal export pier down the street from the Shaneyfelts had rocked the entire Curtis Bay community. Heard for miles across Baltimore and the harbor, pent-up methane gas, sparked by ever-present airborne coal dust, had not just shaken homes, but blown out the windows of houses and buildings closer to the facility, sending shattered glass everywhere and huge plumes of black smoke and toxic coal particles all over the neighborhood.

The scale of the 11:24 a.m. explosion was surreal. Dennis Bright, drinking a cup of coffee when his kitchen windows blew in, thought a military bomb had detonated. Community association board member Meleny Thomas said it was as if someone had picked up her house “and dropped it back down.” Auto mechanics at a commercial shop adjacent to the CSX plant initially believed an aircraft had crashed into their building. One mechanic, who’d been a contract employee at the coal pier just months prior, told a local TV station that he felt lucky to be alive after learning what had happened—although, incredibly, no one was injured in the explosion.

Patrick Shaneyfelt, who’d just left home on a Dunkin’ Donuts run, was sure he’d been rear-ended when the blast wave smacked his Honda. “It felt like the back of my car had been lifted off the ground,” he says, shaking his head. “I pulled over and looked in the mirror. I didn’t see the smoke until I turned around. People gathered in the street, trying to understand what happened. Then they quickly realized it wasn’t safe to be outside because of the cloud of coal dust overhead.”

The CSX coal export facility at Curtis

Bay. Nearly 30 percent of all U.S. coal exports

are shipped from Baltimore.

he terrifying explosion at the 107-year-old pier, where coal exports have soared in recent years, would be an extraordinary event almost anywhere but Curtis Bay. Seismic industrial accidents, however, are all too familiar in the community of 3,500 residents, a mash-up of descendants of early Eastern European immigrants, Appalachian and World War II-era Great Migration workers, and, more recently, an increasing number of Latino families. (At a recent community meeting discussing, in part, the ongoing coal issue, a young Latina woman served as an informal translator for Spanish speakers on Zoom, which would’ve been unnecessary only a few years ago.) In other words, it’s a complicated Black, brown, and white working-class neighborhood today, where three-quarters of all students qualify as economically disadvantaged. It’s also a resilient community that has been fighting the worst air pollution in the state for half a century.

Asthma-related hospitalization rates are three times the national average. The share of deaths caused by chronic lower respiratory disease is nearly 75 percent higher than the rest of Baltimore. Disinvestment, blight, and its consequences—open-air drug markets, sex trafficking, and violent crime—are a whole other shared struggle. Life expectancy overall is 17 years shorter than in the city’s most prosperous neighborhoods, which by no coincidence are far removed from the peninsula’s heavy industry, diesel trucks, coal dust, and Baltimore’s two incinerators and largest landfill.

Four years before the 2021 coal explosion, a cloud of chlorosulfonic acid leaked from Solvay Industries, forcing Curtis Bay residents to shelter in place. Three months after the coal eruption, an explosion and three-alarm fire engulfed Petroleum Recovery and Remediation Management on Curtis Avenue, killing an employee, and again sending billowing black smoke over the community.

Explosions, fires, oil spills, train derailments, chemical leaks, illegal dumping, lead, mercury, and other emissions—and related evacuations, employee deaths, and cancer issues—dot a troubling timeline going back to a massive 1913 refinery fire that threatened to obliterate homes on the 1,300-acre peninsula and a 1927 munitions explosion that sent 150 families scrambling for safety.

In fact, before two coal-fired power plants just over the Anne Arundel County line implemented state-mandated pollution control technology, Curtis Bay was not just the most overburdened community in Maryland, but the single-most polluted ZIP code in the country, according to a 2012 study by the Environmental Integrity Project.

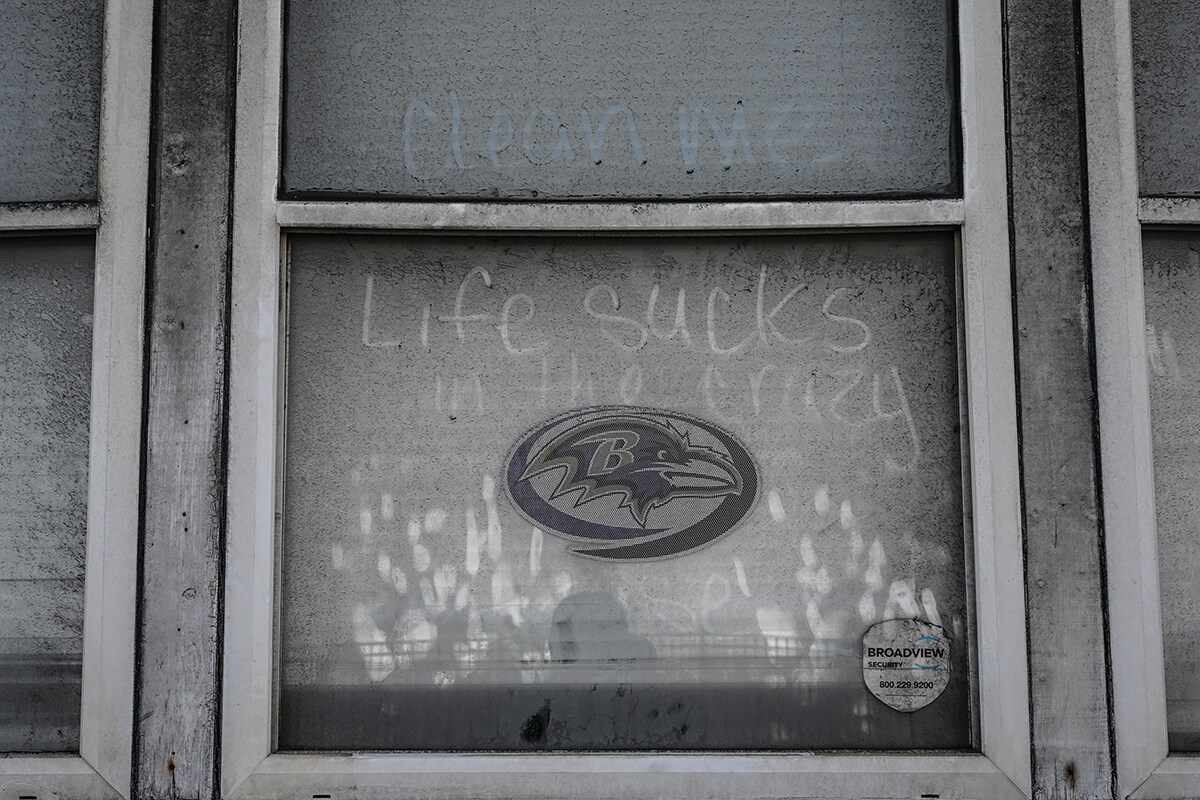

David Jones, a burly, plainspoken traffic-control worker and community association board member, grew up in Curtis Bay. Two decades ago, he and his wife bought his grandfather’s rowhouse, which sits across the street from the CSX coal facility. Initially, the 44-year-old says, wiping a finger across the top of his grime-laden mailbox, he painted the exterior of the tidy home and its white windows every two years. He eventually gave up because the soot quickly grayed over each fresh coat.

Echoing a familiar lament across the community, Angie Shaneyfelt says she hasn’t opened her windows since she and her husband moved to the neighborhood 17 years ago. That was two years after the largest medical waste incinerator in the country, yes, also in Curtis Bay, was cited for more than 400 emissions violations, and a year after two chemical manufacturers were fined for releasing benzene, a known carcinogenic, and xylene, a suspected carcinogenic, into the community. Longtime residents, raising money and awareness through bake sales and bingo nights, tried to block construction of the medical waste incinerator in the 1980s, to no avail.

Towson University professor Nicole Fabricant, an urban anthropology scholar who has studied, written about, and worked with students and activists in Curtis Bay, compares Curtis Bay to places like Flint, Michigan, and Louisiana’s Cancer Alley. “The harms of these industries,” she says, “are woven into the daily fabric of people’s lives.”

Dust on a Curtis Bay window along

the June protest route to the CSX coal facility.

t the moment, among the myriad environmental problems plaguing Curtis Bay is a trifecta of pressing issues. The first is a civil rights complaint filed with the EPA by Curtis Bay and South Baltimore activists regarding the Department of Public Works’ 10-year solid-waste management plan and the city’s “trash-to-energy” incinerator known as BRESCO. That towering smokestack billowing dense white smoke as you come into the city on I-95? It is connected to one of the nation’s most toxic incinerators. The complaint, which the EPA is currently investigating, claims the plan and plant disproportionally add to health risks faced by those in Baltimore’s most disadvantaged communities.

The second issue is the medical waste incinerator owned by Curtis Bay Energy, which agreed to pay $1.75 million in state fines last year, after pleading guilty to 40 criminal violations of failing to properly dispose of waste. Earlier this year, community activists working with Johns Hopkins University strategically placed video cameras to keep an eye on the incinerator, which receives most of its medical waste from outside of Maryland and from as far away as Canada. During a recent protest at the incinerator, where activists attempted to present their evidence to management, Greg Sawtell, a co-founder of the South Baltimore Community Land Trust, said they’ve videotaped “dozens and dozens” of potentially hazardous black smoke events emerging from the medical waste incinerator, lasting anywhere from “two minutes to eight hours” and residents continue to witness discharges of black smoke.

The video findings were brought to a city council meeting earlier this year and shared with the Maryland Department of the Environment (MDE). The state has since filed to impose additional fines on the incinerator’s owners and Johns Hopkins has ended its medical waste agreement with Curtis Bay Energy. MedStar Health, which operates 10 hospitals and more than 300 care facilities in the Maryland and Washington, D.C., region, has not, insisting they have no other alternative.

Meanwhile, the third ongoing crisis involves MDE’s new, five-year renewal permit for the CSX coal facility, whose tracks, trains, and Appalachian coal operation were first laid out by the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad in the 19th century. MDE's self-imposed 90-day period for public comment is scheduled to close December 16. There is a tremendous amount at stake—activists are demanding stricter environmental protections from CSX—but ultimate approval of a new permit is a foregone conclusion.

A quick note about coal: While U.S. coal-fired plants are on their way out, global demand for high-quality Appalachian coal is not. Coal exports hit a five-year high in 2023 to meet increasing energy demands, with nearly 30 percent of all coal exports now shipped from Baltimore.

Last year, a landmark study by Curtis Bay community groups in partnership with Johns Hopkins, the University of Maryland, and the MDE, found evidence of “fugitive” coal dust all over Curtis Bay. Residents, of course, have been reporting coal dust problems in the community for decades. Until the study, the state largely ignored the claims, which CSX has never accepted.

“Sometimes you come home and can see footprints on the sidewalk,” Gloria Sipes, then-president of the community association, told The Baltimore Sun in the 1980s.

The joint study, the first comprehensive effort to measure coal dust in the community, found evidence of coal particulate matter in 100 percent of the samples—which were taken outside homes, businesses, a church, park, and school—during three rounds of testing in the late summer and fall of 2023. The study, peer-reviewed and published last week in the journal Science of the Total Environment, concluded that coal dust found its way into the community daily, with coal particles leaving the terminals’ fence line roughly every 90 minutes. It also highlighted that there are no safe levels of fine particulate matter like coal dust, according to the EPA and World Health Organization. Another joint study of coal dust in Curtis Bay, documenting year-long results of air-monitoring sensors in the community, is due to be presented later this month.

Angie Shaneyfelt on the porch of her Curtis Bay home with her husband and one of their twin daughters.

In the short term, activists want the new coal permit to require that the coal trains and coal piles at the CSX facility be covered, along with stricter monitoring and enforcement mechanisms. Right now, the five-story piles of coal, and associated dust, are only tamped down with sprinklers, while open coal cars extend for miles through South Baltimore. Longer term, they want the coal gone altogether. “They can export something else,” Sawtell says.

The ongoing coal controversy, however, leads to a broader question. Why is the state legislature and the current administration in Annapolis, who say they are intent on tackling climate change, allowing more coal than ever—nearly 30 percent of all U.S. coal exports—to move through Baltimore in first place?

Employees

of the Bethlehem

Fairfield

shipyard catch

the ferry across

Curtis Bay to

work, 1943.—Library of Congress

ettled on a steep hill that slides down to its namesake cove, the 4-by-15-block neighborhood of Curtis Bay rests on 97-acres of farmland once owned by a prosperous, formerly enslaved man named William Hall, said to have been the largest African-American landowner in Maryland after the Civil War. Through the mid and late 19th century, the area remained rich Anne Arundel County farmland, sending boatloads of produce to a growing Baltimore City on the other side of the Patapsco River.

The neighborhood’s homes, historic town hall, and water tower were later constructed on alphabetically aligned streets named for trees—Aspen, Birch, Cypress, Elmtree, Filbert—which were encircled by forests with soil fertile enough to yield mushrooms. St. Athanasius Roman Catholic Church, where Mass was said in Polish, was founded in 1891. A survivor of recent Archdiocese church closures, largely because of its thriving Spanish-speaking ministry, St. Athanasius remains a community cornerstone.

Identified with Curtis Bay since 1899, the still-active U.S. Coast Guard repair yard was similarly built on 36 acres of Hall’s former property. Two decades later, Baltimore City annexed Curtis Bay, and during Prohibition, many of the cutters used by the feds to chase rum runners up and down the coast were assembled or overhauled here. During World War II, workers punched in for around-the-clock shifts. It was the same story at the Bethlehem-Fairfield ship-building docks, which churned out 384 WWII “Liberty” ships, more than any other port in the country.

Curtis Bay community association board member David Jones displays the effect of dust accumulation at his home.

In the ensuing American Century, newer grids on the eastern edge of Curtis Bay’s peninsula—Carbon Avenue, Petrolia Avenue, Asphalt Street, Carbide, Chemical, and Ordinance roads—foreshadowed a less illustrative, more ominous future.

Marine, rail, and scrap yards, manufacturing plants, including Davison Chemical—which imported guano from South America and became one of the largest suppliers of fertilizer in the world—as well as foundries, Army munitions facilities, petroleum tanks, the Patapsco Wastewater Treatment Plant, and mountains of Appalachian coal would entirely change the face of the South Baltimore waterfront. In the mid-1950s, Grace Chemical, under contract with the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, disposed of more than 700,000 cubic feet of radioactive waste in the area. In 2002, the U.S. Coast Guard Yard was added to the EPA’s Superfund National Priorities List.

Those early industries pushed out the summer cottages of wealthy Baltimore City residents and pre-industrial-era waterfront resorts and beer gardens. They brought immigrant labor as well and eventually middle class status to Polish and Eastern European households. It’s difficult to put an exact date on when the heyday of union jobs, church oyster festivals, and company softball crossed over to “the neighborhood has changed.” But by the 1970s, many of the livable-wage jobs were gone, and many of the longtime residents, too—off to the burgeoning suburban enclaves in Linthicum and Arbutus.

The banks of Curtis Bay also once included two now-forgotten neighborhoods that were subsumed entirely in the wake of industry.

Fairfield, once designated a “Negro” project area, and Wagner’s Point, a historically white community, were both displaced following a chain of toxic crises on the peninsula in the 1980s and 1990s. The turn-of-the century houses in Wagner’s Point at one time had been home to Wagner Co. cannery workers. But the close-knit neighborhood slowly found itself surrounded by an industrial landscape of smokestacks, gas tanks, dumping sites, and brownfields. Ultimately, residents in Wagner’s Point and Fairfield became pollution refugees, forced to accept relocation buyouts from the city, which gave up on remediation promises. It was not until 2011 that Baltimore City moved out the last two Fairfield residents. By then, one had posted a handwritten “STILL HERE” note on his door with a date next to it in hopes that looters would skip his house. For years, until COVID presented a different health risk, former Fairfield residents held reunions at the Curtis Bay Recreation Center.

“If someone drives around Wagner’s Point, Fairfield, and Curtis Bay, they’ll think it was always like this,” says Jones, providing a “toxic tour” of the almost dystopian, industrial side of the peninsula. “But I used to go to school with kids from Wagner’s Point, who took a bus to our elementary school. We used to ride our bikes and go fishing and crabbing off piers in Wagner’s Point.”

As he drives, he gestures toward one of the 70-some industrial operations in the area, which today include a Sunoco tank farm, too many generically named “energy” and “recycling” companies to count, and Grace Chemical with its disconcertingly green holding pond. There’s also a nearly 75-year-old “rendering” operation in Curtis Bay, which turns animal carcasses into high-protein feed for livestock.

“Companies pop up so fast you don’t know who owns them and what they do, and everything is fenced in and locked up,” Jones says. “I tell people all the time, my house sits on waterfront property and I don’t have any access to the water anymore.”

Meleny Thomas, executive director of the South Baltimore Community Land Trust, in front of one of the organization's recently rehabbed homes in Curtis Bay.

solated from most of Baltimore, Curtis Bay and adjacent Brooklyn are the only neighborhoods in the city that require a bridge to access. However, Curtis Bay and Brooklyn are also linked to a broader group of communities, including Cherry Hill, Lakeland, Westport, and Mt. Winans, sometimes referred to as the “South Baltimore Six.” (Evidence of coal dust has also been found in Mt. Winans, where open CSX cars pass homes, the community playground, and the basketball court.)

A 2019 report from the New School found almost 80 percent of incineration plants are built in environmentally burdened communities with predominantly minority or low-income residents and Curtis Bay, in that regard, hardly sits alone. All six communities rank in the top 3 percent in the state for environmental burden. That’s partly because of their proximity to industry and the city’s trash incinerator, but also because of the spiderweb of interstate highways—I-95, MD-295, I-395, I-695, I-895—that crisscross around South Baltimore.

It is one of many unfortunate consequences of the Francis Scott Key Bridge collapse that afterward, the Hanover Street Bridge became an alternate route for commuters. The main arteries through Curtis Bay, which also now serve as the primary route for trucks (hazardous loads are not permitted in the Baltimore Harbor or Fort McHenry tunnels), are clogged at rush hour these days. The additional traffic has made an already desperate emissions situation even more dire.

If it is not obvious by now, the cumulative pollution sources impacting Curtis Bay and South Baltimore are a lot for anyone to get their head around. As such, the cumulative sources and their combined impact on the community have never been addressed by city or state officials. Rather, each individual pollution source, in Curtis Bay and in Maryland, is regulated by the appropriate city, state, or federal agency as if it’s a standalone entity. It’s the biggest problem of all for communities like Curtis Bay, says Sawtell, an organizer who has been working on community environmental issues for nearly 20 years. “It is not one thing,” he says. “It’s everything.”

In 2013, MIT researchers, tracking ground-level emissions from sources such as industrial smokestacks, incinerators, and marine and rail operations, found Baltimore had the country’s highest emissions-related mortality rate.

That study, mapping more than 5,600 cities, estimated that 130 out of every 100,000 Baltimore residents die each year due to long-term exposure to air pollution. Which means four times more Baltimoreans die each year from air pollution than, for example, gun violence.

Meleny Thomas, a Hood College graduate, moved to Curtis Bay almost two decades ago to lead a nonprofit after-school program at Ben Franklin High School. She understands the lay of the land well enough to call the six South Baltimore communities “the real South Baltimore.” Her point, of course, is to distinguish the area from upscale Federal Hill, Riverside, and Locust Point on the south side of the Inner Harbor. (Port Covington, the work-in- progress neighborhood rebranded by its developers into a glitzy waterfront known as “the Baltimore Peninsula,” certainly falls in with the tonier neighborhoods.)

Rarely visited by Baltimoreans from outside its boundaries, let alone Inner Harbor tourists, Curtis Bay and the South Baltimore Six are generally out of sight, out of mind to elected officials as well. None, for example, attended September’s Curtis Bay community association meeting. At a standing-room only townhall in October where MDE officials presented their new proposed coal permit requirements for CSX, only local City Council member Phylicia Porter showed up. She expressed her opposition to the permit, but spoke for less than 30 seconds and afterward said it was unlikely that the Council as a whole would not take any formal stance against the renewal of CSX's permit.

CSX trains entering the Curtis Bay community with coal for export.

In a city commonly divided into two narratives—“the white L” and “the Black butterfly”—South Baltimore is its own universe, suffering from a tangled legacy of segregation, economic hardship, and environmental neglect.

“When I first moved here, I felt a lot of racial tension,” says Thomas, who is Black and holds a PhD in public policy. “People who had the means had left, and Blacks and different community members had moved in. The deeper truth, I learned, was that the community had been ‘yellow-lined’ [a cousin of FHA redlining] years before, listed that way because of an influx of ‘Negroes and industry.’ It is not an accident that our community is overburdened by industries, particle dust, and chemicals.”

But she doesn’t think the chicken-and-egg question of which came first—the pollution or the poverty—is the correct framing. Rather, she describes a spiral of discrimination, pollution, flight, and disinvestment begetting more discrimination, pollution, flight, and disinvestment.

“We’re still dealing with these ingrained aspects of segregation, exclusion, and trauma,” continues Thomas, a co-founder of the South Baltimore Community Land Trust, which, along with working on environmental issues, aims to develop permanently affordable housing. “Baltimore has been intentional in creating these economic and environmental problems. A lot needs to be undone, but it’s not going to happen overnight, because we didn’t get into this trouble that we’re in overnight.”

In a recent Maryland Matters op-ed, Michael Middleton, a Cherry Hill native and poverty and housing lawyer, and Dr. Sacoby Wilson, a professor in the University of Maryland’s department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, described the six South Baltimore neighborhoods as a “sacrifice zone.” They called for legislation to address the kind of multi-source, compounding burdens that harm these communities. Laws to address collective impacts have recently been passed in Minnesota, New York, and New Jersey. A hoped-for effort in the Maryland General Assembly failed last year when state legislators were willing to address clean water problems, but balked at air pollutants.

In preparation for the upcoming General Assembly session, members of the South Baltimore Community Land Trust and the Community Association of Curtis Bay have worked with policy and legal experts to craft new cumulative air pollution legislation. Tentatively titled, The CHERISH Our Communities Act, Sawtell says they are now looking for sponsors in the state House and state Senate.

Meanwhile, many Curtis Bay residents feel like they are losing the battle. They are worried that the city’s planned, new rec center, set to replace their 1950-built community hub, is the next step in their displacement in the name of industry. It’s slated to be built not in Curtis Bay, but neighboring Brooklyn.

ncredibly, in 2010, a third local incinerator was nearly constructed even as Baltimore stood as the U.S. city with the most deaths caused by air pollution, with Curtis Bay as its dirtiest neighborhood. The incinerator proposal won the backing of then-Gov. Martin O’Malley, then-Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, and state and city officials. That year, the Maryland Department of Energy approved a permit for the facility, which would have become the largest trash incinerator in the country, burning 4,000 tons of garbage daily and emitting up to 1,240 pounds of lead and mercury annually.

In concept, the new incinerator would have been similar to the existing BRESCO incinerator, the so-called “trash-to-energy” facility that went online in 1983. Remarkably, state legislation was later passed and signed by former Gov. O’Malley that qualified BRESCO for renewable energy tax credits, which it retains to this day despite accounting for a third of all industry emissions in Baltimore City. The new MDE-approved $1-billion project was to be on the property of a previous chemical manufacturer in Fairfield, whose residential population, as noted earlier, had conveniently already been displaced.

Angry about getting dumped again, students, parents, and teachers at Benjamin Franklin High—less than a mile from the planned incinerator—formed Free Your Voice in opposition. The youth-led group joined with other environmental organizations and mobilized Curtis Bay over a four-year campaign of public education, protests, and testimony in front of city leaders.

A turning point came when students learned that city agencies, local nonprofits, and Baltimore City Public Schools had contracted to purchase energy from the incinerator, prompting a student presentation at a school board meeting and a demand that officials pull out of the agreement to protect their health. Garnering national attention, they ultimately blocked construction of the third incinerator in 2016, a David vs. Goliath victory. Destiny Watford, a Free Your Voice leader, earned an international Goldman Environmental Prize for her efforts.

A subsequent generation of Free Your Voice students were still active at the high school when the 2021 CSX explosion re-galvanized protests in Curtis Bay.

In June, on the heels of $1.75-million class action settlement with CSX around the explosion, Free Your Voice leaders, members of Baltimore’s Green Party, and other residents and advocates rallied at the familiar Curtis Bay rec center to make the case that the settlement had not solved the underlying coal issue.

They marched to the coal terminal, reiterating opposition to the handling and exportation of coal in their community. As they proceeded down Pennington Avenue, one block west of the coal facility, other residents came out to see and, for some, to cheer on, the procession. “I just moved here,” said one man, stepping onto his front stoop with his dog and child, running his hand across his dust-covered siding, holding up his dust-covered fingers for inspection. “I had no idea it was this bad.”

Angie Shaneyfelt revealing black dust outside and inside her rear bedroom window.

Chanting slogans like “No more coal, no more oil, keep your carbon in the soil,” marchers placed a handmade “Eviction Notice” on the CSX fence.

Angie Shaneyfelt and David Jones remain frustrated that it took so long to convince the state the problem was real, and the subsequent lack of urgency in addressing the results. They worry that after CSX’s post-explosion fine, $15,000 to the state and $100,000 to the community—and the $1.75 million settlement, about $3,000 per household—it will be back to business as usual.

Railroads, given their interstate nature, are challenging for state officials to regulate, but activists also believe elected leaders are more interested in protecting corporate interests and the city and state’s tax base than Curtis Bay residents. And while Baltimore’s coal terminals are privately owned, coal exports qualify the city as an “energy transfer” port, which typically makes the Maryland Port Administration eligible for around $5 million in federal monies that can be used for harbor dredging operations.

“We’re not getting help from MDE,” says Jones, becoming animated. “Companies pay a fine and continue to do what they do. CSX’s position is they have been here longer than anybody else, and that’s true. [B&O erected its first coal shipping facility in Curtis Bay in 1882.]” The community is more transient today, he says. Activists move on or they die. CSX can wait everyone out.

A still image from a January 26 black smoke event from the Curtis Bay Energy medical waste incinerator, one of many documented by local activists over the past year. —Courtesy of the South Baltimore Community Land Trust

CSX, which posted more than $14.6 billion in revenue in 2023, says it has invested $60 million at its Curtis Bay plant over the past five years to improve safety. The company also did their own study, which disputed the findings of the Hopkins, Maryland, and MDE researchers, faulting collection methods and flawed statistical models. They also claimed the documented coal dust compounds were not necessarily from their pier, but other polluters.

In September, however, the state Department of the Environment was forced to issue another notice of violation to CSX. Several activists, including Sawtell and a film crew with a drone camera, were gathered by chance outside the rec center, capturing a dust cloud caused by a rail track cleaning, emerging in real time. A similar cloud was witnessed the next day by residents.

In September, however, the state Department of the Environment was forced to issue another notice of violation to CSX. Several activists, including Sawtell and a film crew with a drone camera, were gathered by chance outside the rec center, capturing a dust cloud caused by a rail track cleaning, emerging in real time. A similar cloud was witnessed the next day by residents.—Courtesy of the South Baltimore Community Land Trust

Activists during

the June march

to the CSX coal

pier.

hashawnda Campbell, now 27, was one of founding student members of Free Your Voice during the successful campaign to halt a third incinerator. Today, she is a South Baltimore Community Land Trust leader, toting the bullhorn during the June march to CSX from the Curtis Bay rec center.

As a teenager, she often hung out at the weathered rec center and surrounding playground and park, which once included a functioning swimming pool, but no longer. Warehouses obscure the view of the coal piles across the street, but that was not the case when Campbell was a teenager. There aren’t many spaces in Curtis Bay where kids can go, so that was the place to sit and talk after school.

“So, we knew about the coal, just like we’d seen all these different industries and smokestacks,” says the outgoing Campbell, who is now a mother. “We lived by the coal. We walked next to it. We breathed in the coal dust and everything else. As kids, you don’t pay attention.”

At the same time, she played basketball, and volleyball for a while, and ran track. All the sports teams at Ben Franklin struggle, then and now, she says, to deal with students’ asthma. “My teammates had to be subbed out more often than any other school,” she recalls. “They had to sit out for long periods. It wasn’t until Free Your Voice started that we began to understand what was happening. I go back to school to talk to students and ask how many have asthma or how many have someone in their family that does, and the hands shoot up. If you go into the school, you’ll see kids sharing asthma inhalers.”

Several years ago, with Fabricant, the Towson professor, and a few of her students, Campbell made a trip to West Virginia to see the mountain communities where the coal originates, some of the same places that have been sending coal to Baltimore since the 1880s.

A new mine, in fact, which is expected to send coal to Baltimore for the next 20 years, was recently opened near Philippi, where the original 1911 B&O Railroad Station serves as home to the county’s historical society museum.

Most coal exported from Baltimore is steam coal, used overseas for electric power and industrial heating, with India the largest importer. In 2023, Baltimore’s steam coal exports, which include those from Consol Energy’s Consol Marine Terminal—located near the Seagirt Marine Port in Dundalk and away from residential communities—rose to 19 million tons, up from 12 million in 2022. More than 9 million tons of metallurgical coal, burned in coke furnaces for steel-making, were exported from Baltimore in 2023, up from 8 million in 2022, with Japan, China, Brazil, the Netherlands, and South Korea as the largest importing countries.

The sidewalk outside the Curtis Bay rec center, which reads “Coal Kills.” Shashawnda Campbell, co-founder of the South Baltimore Community Land Trust.

Exporting increasing amounts coal would seem to cancel out the climate change-minded state legislation passed two years ago, which set a goal of a net-zero carbon Maryland by 2045. But elected officials, including Gov. Wes Moore, who has touted the net-zero effort, have not committed to reducing coal exports.

In 2022, residents in Richmond, California, a working-class city northeast of San Francisco, whose environmental burdens include major freeways and a Chevron refinery, convinced its city council to negotiate a deal with the operators of its shipping terminal to stop exporting coal.

How long will U.S. coal production continue apace? According to the EPA, there are recoverable reserves at present rate to last another 420 years.

“We have to stop shipping this stuff out, period,” Campbell says. “There has to be a change in mindset at the highest levels to stop production of coal, but [politicians] aren’t willing. The only people benefiting from this coal are the companies that are mining, transporting, and exporting the coal. They are making money. We’re not benefiting from it, but it affects our lives on a daily basis.”

Campbell mentions the consequences in West Virginia, too, connecting the dots between communities there that have suffered environmental health issues, the workers who have died in mines, the long-standing problems in Curtis Bay, and climate change, which impacts everyone, everywhere.

“They will keep exporting coal until there is no Curtis Bay left, until it is all industry,” she says. “But we’ve got to stop looking at this coal and these issues like they’re only a South Baltimore problem. They’re part of a bigger picture.”