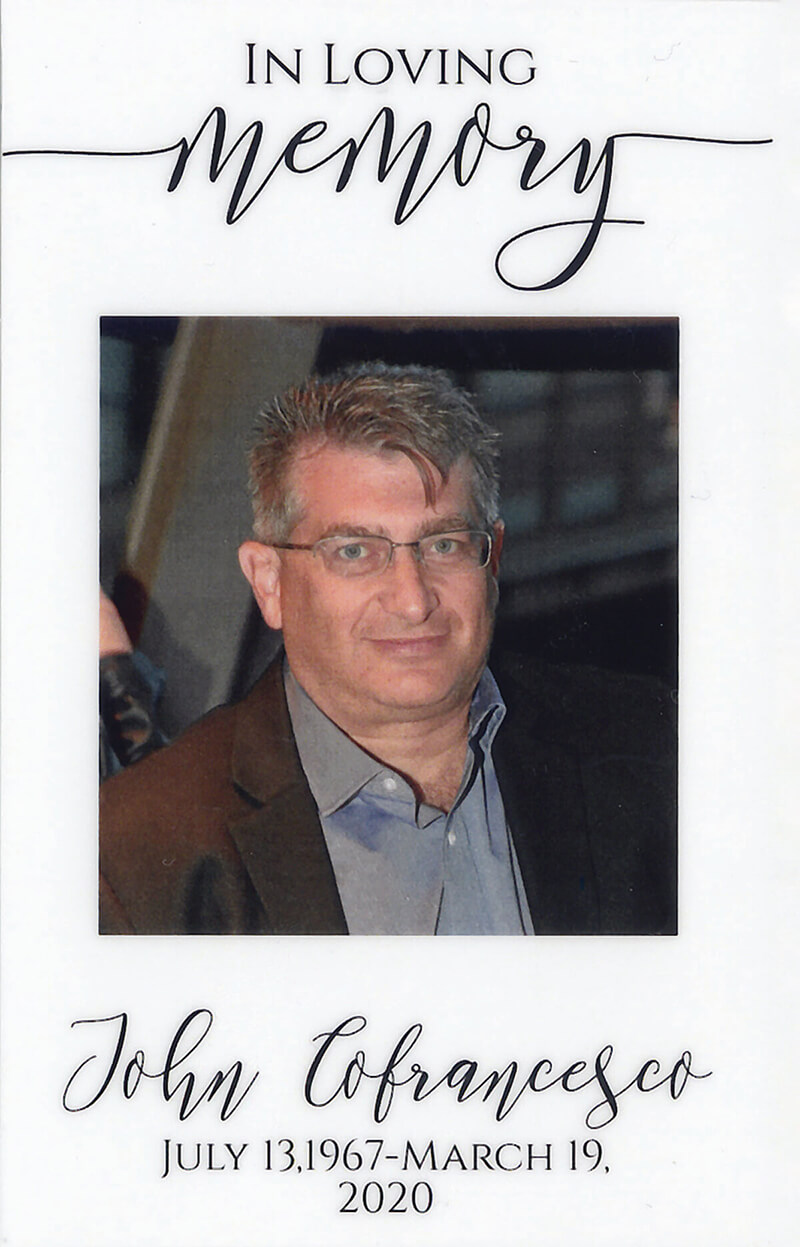

No Average Joe

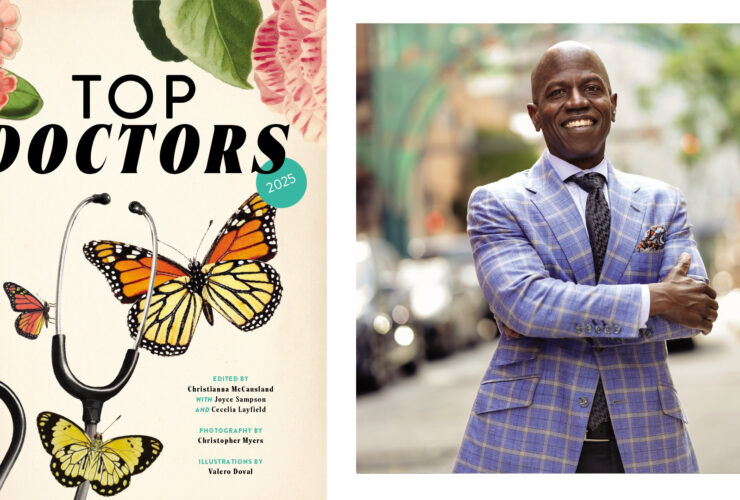

Health & Wellness

No Average Joe

As he pushes past his own personal pain, Dr. Joseph Cofrancesco continues to dedicate his life’s work to helping others.

HEN JOSEPH COFRANCESCO was getting his medical education—as a student at Mount Sinai School of Medicine, an intern at Columbia Presbyterian, then a resident in primary care at Albert Einstein College of Medicine—the AIDS epidemic was raging. And at that time, New York was affected by the deadly disease more than any other city in America.

“In the late ’80s, when I was in training, AIDS was full-blown,” says Cofrancesco. “We heard stories about patients having their food trays left outside the door and nurses refusing to go in their rooms. Fortunately, I never witnessed that, but it was still a pretty frightening time— and there was no New York Times article for the first 100,000 dead. The president [Ronald Reagan] never even said the word ‘AIDS.’”

Mostly what Cofrancesco recalls of those days is the suffering he saw. “When I was in med school, everyone with AIDS died,” he says. “And when I was an intern, we had [the drug] AZT, which people took every four hours through the night, and made everyone sick. Patients lasted maybe six months, then got sick and died. People were dying all around, and no one seemed to care. It was awful.”

The disease, he says, left its mark not only professionally, but personally. “It was scary and really depressing,” he says. “You’re in New York, and you’re young and it’s fun. You go to parties and clubs, and then suddenly half of your cohorts die, and all of your weekends are spent going to memorial services.” Bearing witness to so much death in his early 30s gave the doctor a particular lens on life. “It made me keenly aware that these patients were my age and they were going to die,” he says. “It puts things in perspective in terms of how you approach the whole life cycle.”

In 2020, Cofrancesco would have to summon that perspective again, this time when dealing with the COVID-19 crisis, and a tragic loss that hit much closer to home.

Cofrancesco vividly remembers working that first day on the COVID unit, less than three weeks after losing his brother.

OFRANCESCO HAS PACKED a lot into his 62 years. The second oldest of four boys, he was the first to attend college in his close-knit, Italian working-class family—and he has continued to distinguish himself ever since.

At The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, where he’s practiced and taught for more than 23 years, he has worn many hats, including working as an attending physician with expertise in general medicine and HIV care. In addition to seeing patients, he is the director of The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institute for Excellence in Education and a professor of medicine who works closely with medical students, residents, and fellows, and is known for his superior teaching skills.

Despite his 26-page C.V. filled with impressive accomplishments (such as lecturing and teaching internationally, publishing countless pieces in leading medical journals, and earning dozens of awards), Cofrancesco, who is small in stature, has an easy laugh and immediate warmth and charm.

Those who know him—from colleagues to patients to friends— speak about him in superlatives and with genuine affection. (The family of one patient who passed away even presented him with a thankyou plaque at their loved one’s funeral.) He is affectionately known as “JoeCo” or “Dr. Joe” around the halls of the hospital.

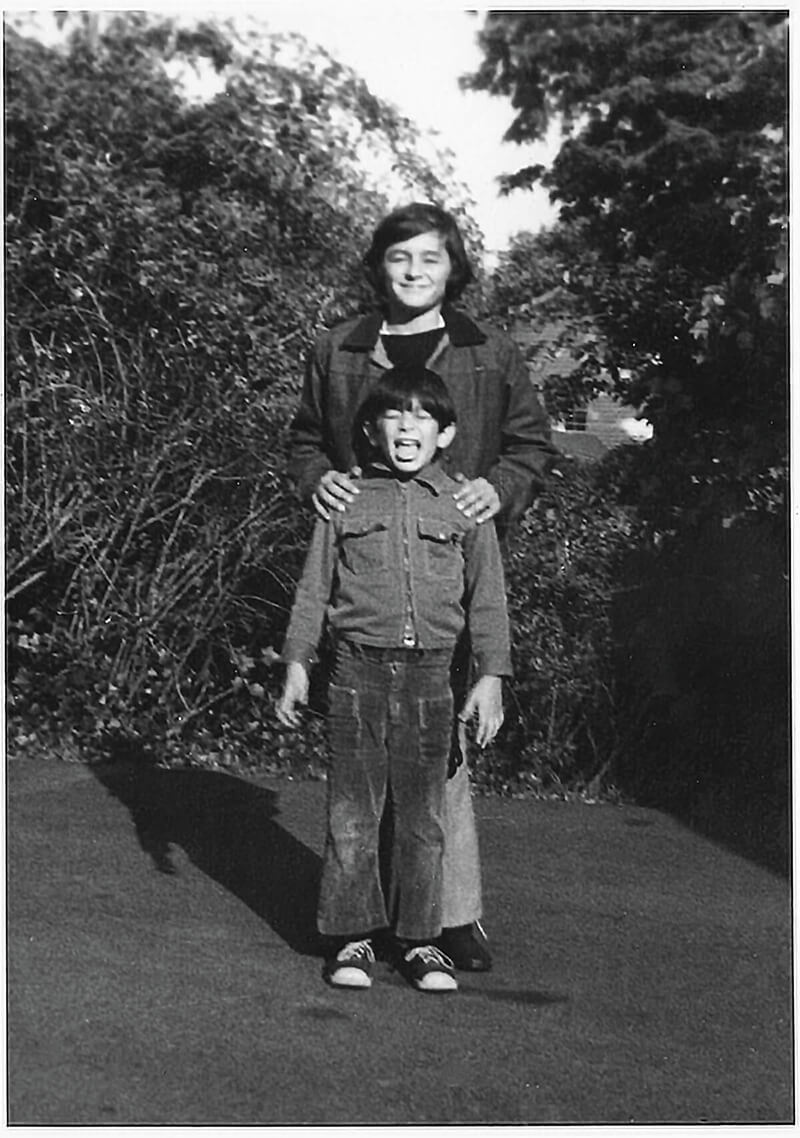

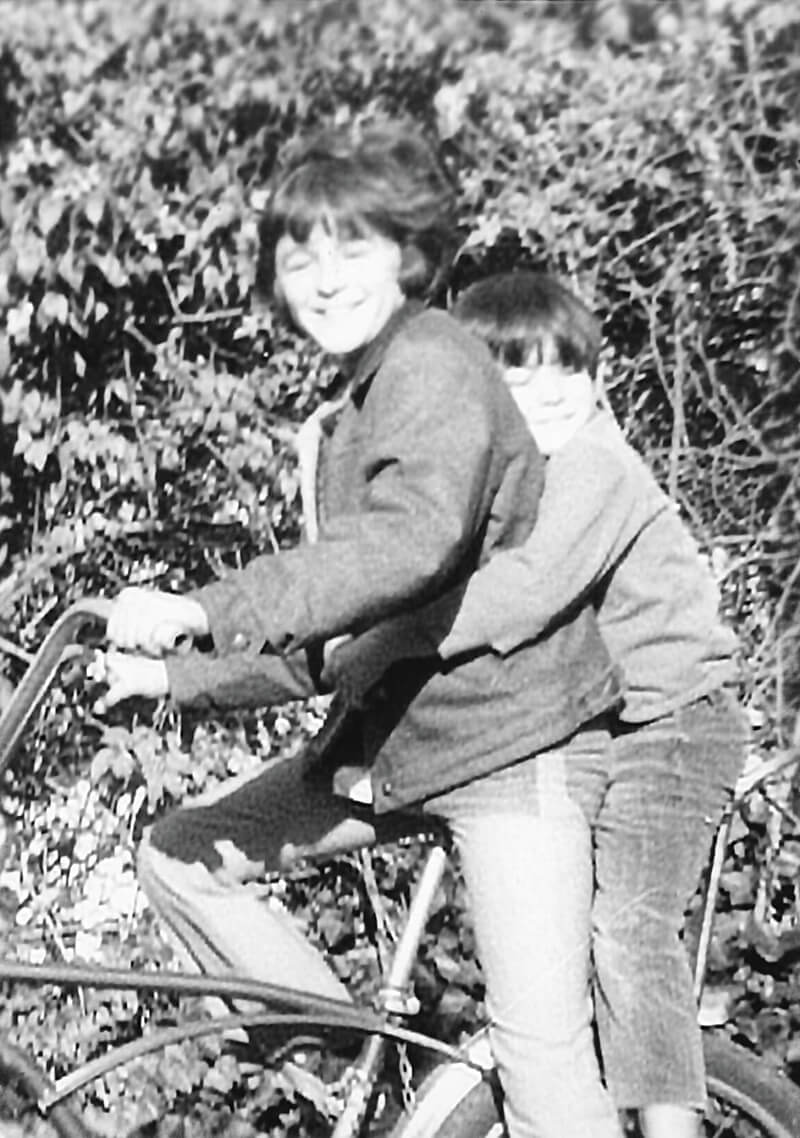

Dr. Joseph Cofrancesco with his younger brother, John, in Elmwood Park, New Jersey, where they were raised.

E IS THE most amazing advocate to his patients and the most thorough doctor I’ve ever seen in my life,” says John Shields, the owner of Gertrude’s Chesapeake Kitchen and Cofrancesco’s longtime patient and friend. “Every patient gets the same amount of attention. I think that comes from him working in a war zone during the AIDS crisis and being this fierce advocate who was trying to save lives. Hopkins has so many doctors—and even there, he is a legend, a gifted doctor, and a gifted teacher.”

Randallstown resident Pat Goins-Johnson, both of whose parents Margaret, 90, and James, 87, have been Dr. Cofrancesco’s patients for 20 years, echoes that sentiment. “My mother has had quite a few medical issues,” she says, “and he’s right there on top of them. We couldn’t ask for a better doctor when it comes to taking care of my parents—he treats us like family members.”

Perhaps his most famous patient is eager to weigh in, too. “Dr. Cofrancesco is the perfect doctor,” says filmmaker John Waters. “He respects my privacy, relentlessly tests me for diseases I didn’t even know I could get, and skillfully looks deep inside my body with an intelligent medical curiosity I totally trust. On top of that, he’s got a great sense of humor. I never knew you could blurb a doctor, but I just did,” he adds.

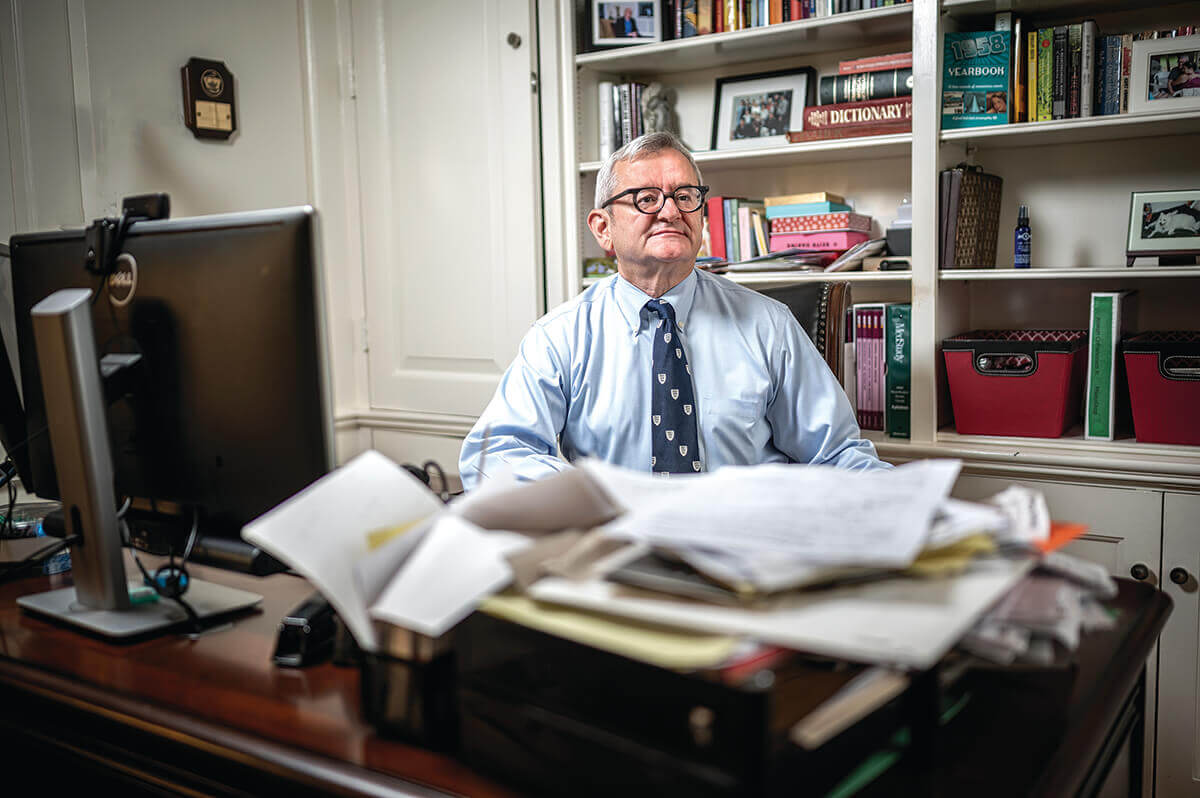

Dr. “JoeCo” in his home office, where he now sometimes Zooms with his patients.

OME TWO DECADES since finishing his residency, Cofrancesco finds himself on the front lines of yet another war zone, as the novel coronavirus brings back echoes of the AIDS crisis.

But today, the experience is even more gut-wrenchingly personal. On March 19, his 52-year-old younger brother John, who ran a nursing home in northern New Jersey, succumbed to the coronavirus. John’s wife, Angela, a nurse at a different facility, was also hospitalized with the virus, but survived. “The nursing homes were ground zero,” says Cofrancesco from behind a mask in the living room of his elegant 1930s Lutherville home. “And he was going in day after day after day to a place that was virus central.”

When his brother first fell ill in early March, it wasn’t immediately obvious that he had COVID. “We thought he had a cold,” says Cofrancesco, “but it was lingering too long. It seemed like maybe he was getting a little bit better, but then he got worse.” Eventually, John landed in the hospital, where he was diagnosed with double pneumonia. “They said this may well be COVID,” recounts Cofrancesco. “He was on oxygen and they did the hydroxychloroquine and antibiotics. He was again teetering, but getting worse and worse. By then, his doctors said that it was a classic case of COVID. The last time I spoke with him was before he got intubated in the ICU.’”

As John was placed on a ventilator to help with his breathing, Cofranceso tried to allay his brother’s fears, all the while feeling fearful himself. “When he said to me that he was afraid, I said, ‘What are you scared about? You’re a young guy. You have no medical problems and you’re completely healthy. Think of this as the machines giving your lungs a rest. They will intubate you and things will settle down,’” Cofrancesco recalls telling him. “They put him on 100-percent oxygen, and the longer he was on it, I knew this wasn’t good.”

While his doctors hoped to enroll John in a drug trial, they awaited the results of his COVID test. “They tried to get him on a Remdesivir study, but the positive results had to come back, even though they knew it was COVID,” says Cofrancesco. By the time the results came in, seven days from the time he was tested, it was too late.

At three in the morning, the doctors called to deliver bad news. “It was the doctor saying, ‘Your brother’s heart just stopped but we are coding him now,’” he says. “I was staring at the ceiling thinking maybe, maybe, he’d come through, but I knew in my heart that he wouldn’t. And then, of course, I got the call 40 minutes later that he didn’t make it—I was completely crushed.”

To make matters worse, because New Jersey was a hotspot at the time, Cofrancesco could not reunite with his family. “The loss of my baby brother really hit me hard,” he says. “We were close, and we spoke a lot near the end. I’ll never get over it. We couldn’t have a service or do anything. But I’m not one to sit home and wallow. When you get older, and a younger relative asks, ‘So what did you do in the war?,’ how are you going to answer it? You take a few days to mourn—and then you do what have to do.”

Cofrancesco had to do what he’d always done—roll up the sleeves of his white coat, and head to the hospital.

Prior to John’s passing, Cofrancesco had originally been scheduled to take a week off. “Instead, it became a week to specifically honor my brother on the COVID unit,” says Cofrancesco, who also volunteered to do additional weeks in the hospital. “I said to Sanjay [V. Desai, Residency Director at Johns Hopkins Hospital], ‘Remember, we all took oaths. We are in a crisis. People are in the hospital, and they are sick, and they need doctors. And we all have to do our part.’”

Desai has known Cofrancesco for more than two decades, ever since he himself was a Hopkins resident. His admiration for his colleague, he says, has only grown through the years. “He does everything just completely selflessly,” says Desai. “Every step he takes is for someone else.”

There are other parallels between the COVID crisis and the AIDS epidemic: It has brought out a lot of fear in everyone, including health care workers who find themselves at risk of contracting the disease.

In both cases, Cofrancesco led by example, showing his colleagues that duty came before fear. “His current passion is rooted in the experience he had when AIDS started,” says Desai. “He reflects on how vulnerable those patients were, how they were ostracized and really rejected by normal society. He saw some of that with COVID—and he refused to let that happen. To have someone whose brother died of this disease say not only are they going to do this one week in the hospital, but more weeks, was a call to arms—it was a charge to everyone— and it was beautiful.”

Dr. Cofrancesco

relaxes in his yard.

OFRANCESCO WAS BORN in Paterson, New Jersey, and raised in Elmwood Park, New Jersey, the second oldest of four boys. His mother, Lucy, is a homemaker. His father, Joseph, is a retired carpenter. “Most of the women stayed home,” he says. “And most of the men were carpenters, plumbers, and electricians. None of them worked in offices, and some of them worked in factories.”

Cofrancesco envisioned a different future. He had always excelled in school, even earning a near-full scholarship to Columbia University, and dreamed of one day being a doctor, a job he now calls “the best job in the world.” Throughout his primary education, he attended Catholic school, where he was “imprinted,” he says, with a strong sense of purpose and serving others. “It sounds corny,” he says, “but helping people felt like the right thing to do. I think my sense of duty came from my parents, but I suspect the nuns in grade school, [as well]. You got this idea that life was supposed to mean something, and there’s this sense of service.”

And though he set his sights on medicine, his life took a detour after graduating from Columbia in 1980. He applied to medical school and was not admitted. “I wasn’t this superstar,” he says. “I applied to med school, and I got interviewed, but I didn’t get in.” Cofrancesco moved on with his life, first working for the Institute of International Education in New York City, where he administered Fulbright scholarships and international exchange student grants. Having been a thespian in college, he did some small-time acting gigs at a studio in Chelsea on the side.

“About four years after college, I was like, ‘What am I actually going to do with my life?’” he recalls. In 1984, he left his job to volunteer at a community clinic for underserved populations on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, studied molecular biology at Hunter College, and took the MCATs again. (“I actually studied the second time around,” he says, laughing.) By 1990, he graduated from the prestigious Mount Sinai, where Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases—on the front lines of the AIDS epidemic at the time—was the keynote speaker. His whole family, and extended family and friends, were there to see him get his diploma. “It was a huge to do,” he recalls.

For Cofrancesco, family remains paramount. Surrounded by books and family photos in his Lutherville home, he remembers his kid brother, John, who was eight-and-a-half years his junior. “We had the kind of relationship where I could read to him and take him to the park,” says Cofrancesco. “He loved Clifford the Dog.” As an adult, he recalls, “he was absolutely dedicated to his son, Dylan, who is now 14.”

Several times a year, his family, including his parents and extended relatives, have historically gotten together on holidays or for special celebrations, either at Cofrancesco’s sprawling house or crammed into one of his brothers’ homes for a traditional Italian Christmas Eve fish feast complete with pasta in white anchovy garlic sauce, carrot salad with hot pepper, and always an abundance of Christmas cookies. Now, with COVID and the death of his brother, he mourns the loss of those traditions—at least for the coming holidays. “My parents are 90 and 94, and we have to protect them,” he says. “We can’t put 18 people around the table. And Johnny won’t be there this year, which will make us very sad.”

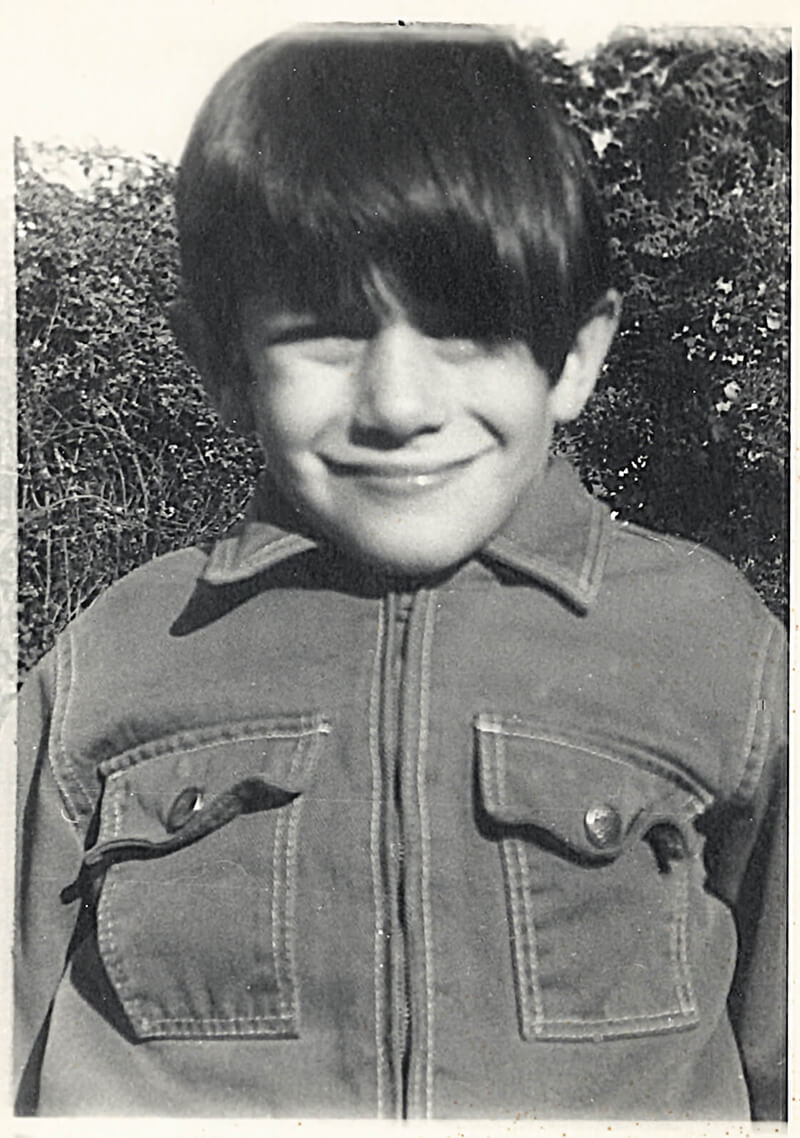

John Cofrancesco as a young boy. A memorial was held for Cofrancesco’s younger brother John in July. A brotherly moment from childhood.

OFRANCESCO VIVIDLY REMEMBERS working that first day on the COVID unit less than three weeks after losing his brother. He donned his bulky personal protective equipment, including a powered air purifying respirator, to work a seven-day shift on one of the COVID units on the seventh floor of the Nelson building.

“He was nervous, but determined,” says Desai. “And he did it in front of the residents—in terms of a role model, you can’t shoot any higher.” But once he entered the unit, with a photograph of John tucked away in his patient binder, he was okay. “I found it oddly calming,” says Cofrancesco, who also worked on a COVID unit for a week in May.

“You think of medicine as having all the answers sometimes,” says Cofrancesco. “and you realize that, right now, and certainly during the AIDS epidemic in the early years, it doesn’t.”

While he’s always been known for being caring and engaged with his patients, because of the way in which his brother died, he has made it a point to spend additional time with the COVID patients. “I know my brother spent his last days in an ICU intubated in a prone position and sedated, and there was no one there,” says Cofrancesco, whose family was finally able to have a mass and a memorial service for John in July. “And that was really hard to think about. I wanted the patients to have a personal connection, so they wouldn’t feel so isolated, knowing full well that not having people visit is awful.’”

While the COVID crisis has been terrifying for the public at large, Cofrancesco emphasizes that hope truly is on the horizon. “You think of medicine as having all the answers sometimes,” he says, “and you realize that, right now, and certainly during the AIDS epidemic in the early years, it doesn’t. But AIDS is now a controllable disease with a combination pill that you take once a day, with relatively few side effects. I think about that now with COVID. We’ve come a long way, and we are certainly not there, and we need to get a whole lot better, but vaccine development is coming at a pretty astonishing pace. It’s only been a few months. My brother died on March 19—that seems like a decade ago in terms of where we are now.”

As he looks back on his own decades in medicine, it all comes back to the bonds he’s formed with his patients, all of whom are uncommonly fond of him. “The big awards are really lovely,” he says. “But the thing I valued the most—at least pre-COVID—was when a patient said, ‘Dr. Joe, can I give you a hug?’”