Health & Wellness

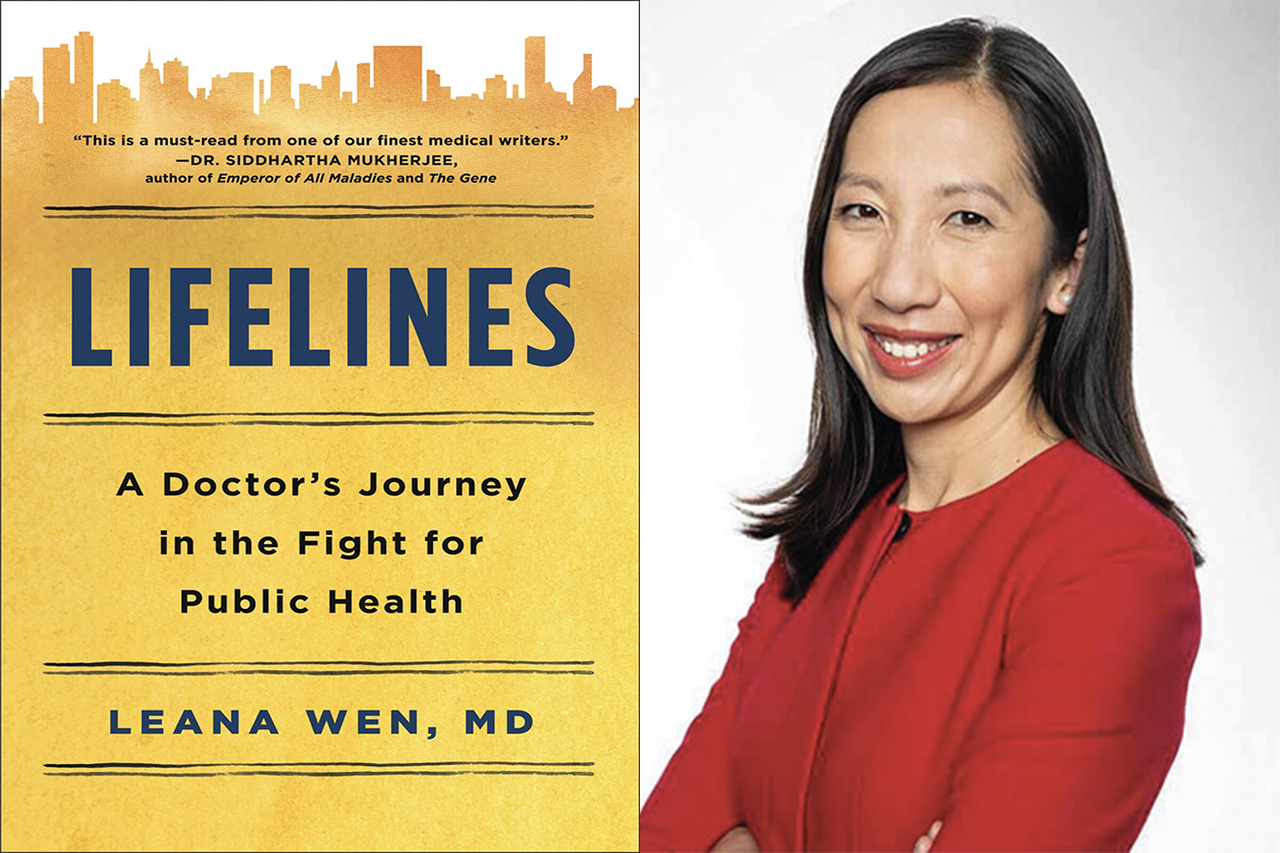

Dr. Leana Wen Shares Personal Struggles and Public Health Approach in New Book

We sit down with the former city health commissioner to discuss her book 'Lifelines.'

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the whole country has gotten to know Dr. Leana Wen, one of CNN’s top medical analysts. Baltimoreans, of course, were already well acquainted with the articulate, data-driven, compassionate former city health commissioner.

Wen oversaw the B’more Healthy Babies initiative, which dramatically reduced infant mortality, and successfully fought to make naloxone—the opioid overdose reversal medication—available over the counter for city residents. Some may also know of her immigrant family’s hardships, but few likely have an appreciation for just how much she overcame.

In Lifelines, Wen shares her personal story and struggles in forthright detail and connects the dots of her public health approach to treating much of what ails this country.

The most compelling parts of your book are your family’s financial and personal struggles during your childhood. Public housing, food stamps, school lunch programs, and state university grants all factor into your story.

I hadn’t intended to [write about that]. I’d initially pitched the book as a way to tell positive stories about public health and Baltimore. In writing the book, I recognized that my story is a story of public health successes, too. There are other stories I shared for specific reasons; for example, my mother’s misdiagnosis, then eventual diagnosis with breast cancer, because I learned a lot of lessons about what it means to be a patient advocate.

You also share intimate accounts of your own physical and mental health experiences, in particular as a woman and mother.

I talk about things like my struggle with infertility, post-partum depression, and growing up with a severe speech impediment because those were such deep sources of stigma, fear, and shame for me. In telling my story, I wanted to help others break down their stigma, fear, and shame with these issues, and whatever else might be challenging sources of concern in their lives. I also share a lot of stories about my mother because being a working mother myself, the idea of work-life balance is something I think about a lot.

How do you define public health?

Here’s the issue with public health. It’s hard to define because it is often what happens when you have prevented something from occurring. There is no face of public health because it usually is successful when it is invisible. We have the face of a child who was lead poisoned, but what about the home remediation that was done to prevent a child from getting lead poisoned? I see public health as addressing all the elements of health and well-being. The elements of housing as health care. The food that we eat. Public health can be a powerful tool to level the field of inequality.

You were fairly young when you were selected by Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake to lead the City Health Department.

I was 31, but let me point out that Dr. Joshua Sharfstein and Dr. Peter Beilenson were both in their 30s when they were selected. I think we have a history in Baltimore of selecting individuals who have a bold vision and track record from an early age of not being afraid of difficult challenges.

You say at one point in the book that public health requires public trust.

I am very concerned about how public health has become a pawn in partisan politics. Even the idea of people going door-to-door to educate on mask wearing and vaccines somehow has been misunderstood as an attempt to take away people’s guns. How did that happen? Or look at Tennessee, not only has the state health department been asked to stop outreach to adolescents about the COVID vaccines, they’ve been asked to stop outreach about vaccines in general, including messaging about measles and polio vaccines. This [lack of trust] is a serious threat to public health.