Health & Wellness

Matters of the Heart

More than 90 years ago, a Johns Hopkins electrical engineer invented the defibrillator and paved the way for modern-day CPR.

By Mike Unger

Illustration by Celina Pereira

Thanksgiving, Nick Kouwenhoven made an exciting discovery. While moving boxes of family papers, he stumbled upon a previously unknown accounting of some of his grandfather’s work in the mid-20th century. Unlike most, he already had a vast knowledge about the accomplishments of William Kouwenhoven, a not-quite-household name who should be one. The elder Kouwenhoven, a colorful character who was sometimes called Wild Bill, could have another moniker as well: the Father of CPR.

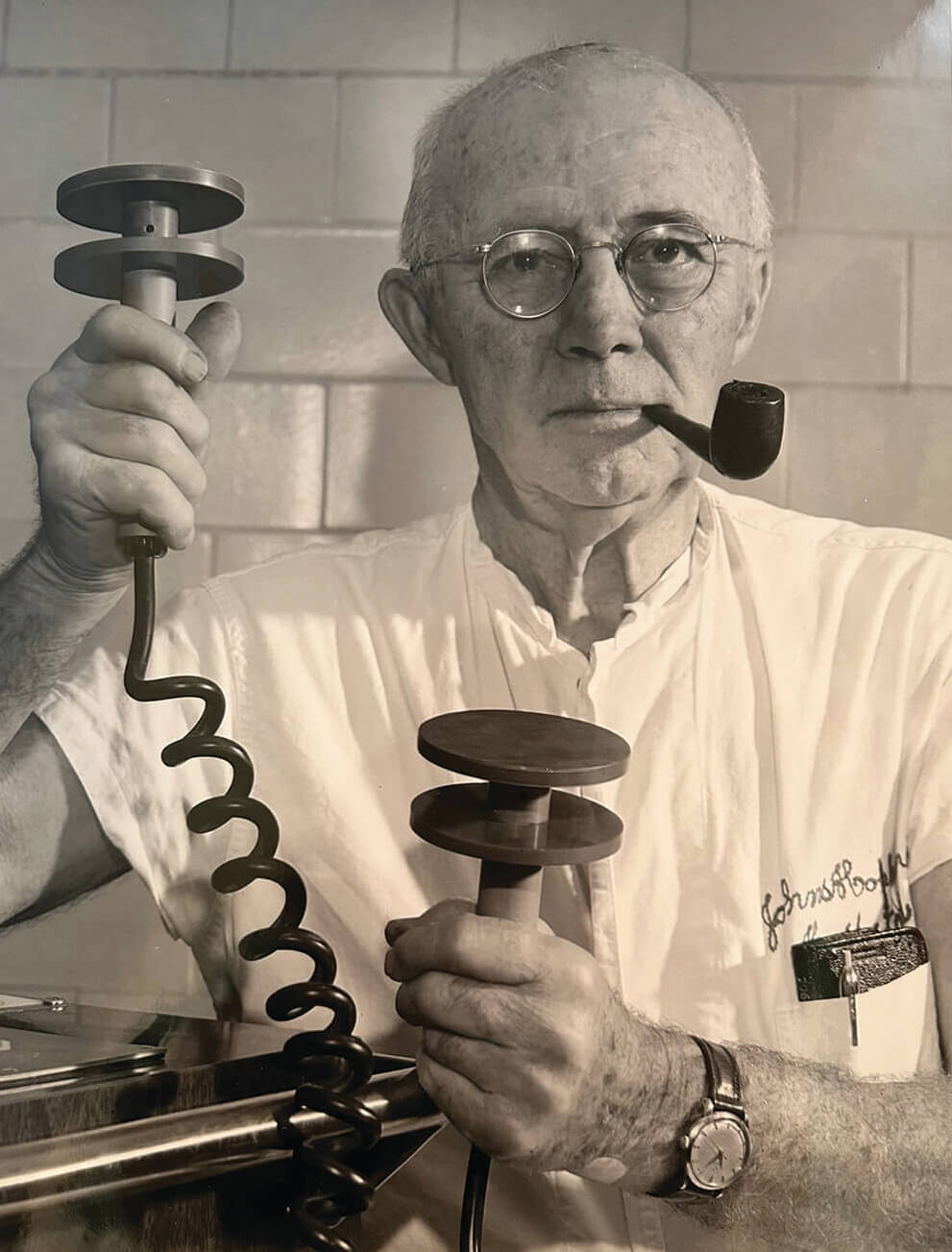

Kouwenhoven, along with key colleagues at Johns Hopkins University, was largely responsible for the invention of cardiopulmonary resuscitation—now universally known by those three letters—and the defibrillator, a method and a machine that have impacted humanity in innumerable ways.

For that, the whole world should give thanks.

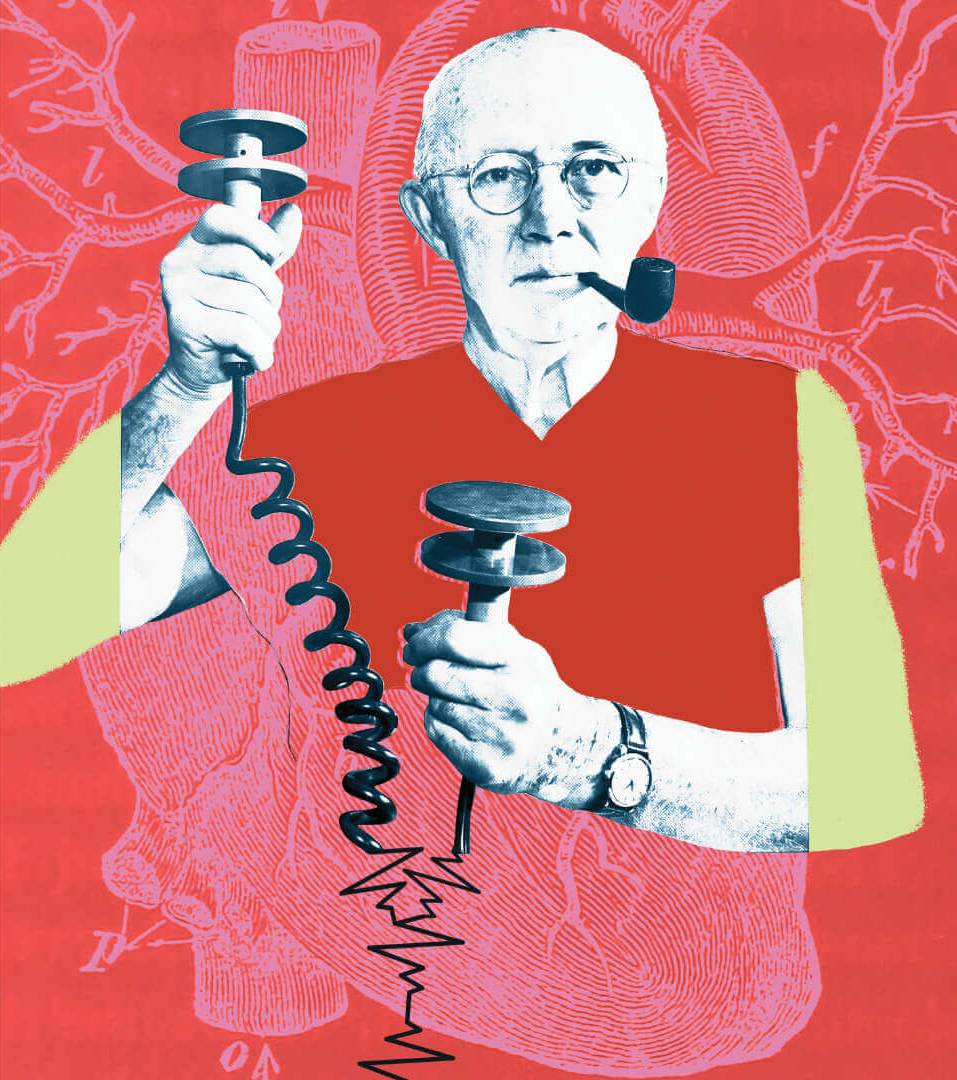

William Kouwenhoven received the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine’s first-ever Honorary Doctor of Medicine in 1969. —Courtesy of Johns Hopkins Whiting School of Engineering

Most people who learn CPR—the series of chest compressions, sometimes including rescue breaths, performed when the heart stops beating to keep blood flowing to the brain and other vital organs—never need to use it. But knowing it can mean the difference between life and death for someone in cardiac arrest. That was famously demonstrated a year ago when Buffalo Bills safety Damar Hamlin collapsed on the field during a Monday night NFL game in Cincinnati. While terrified teammates looked on, medical personnel used CPR and an AED (an automated external defibrillator, a portable machine that sends an electrical shock to the heart to return it to a normal rhythm) to revive him.

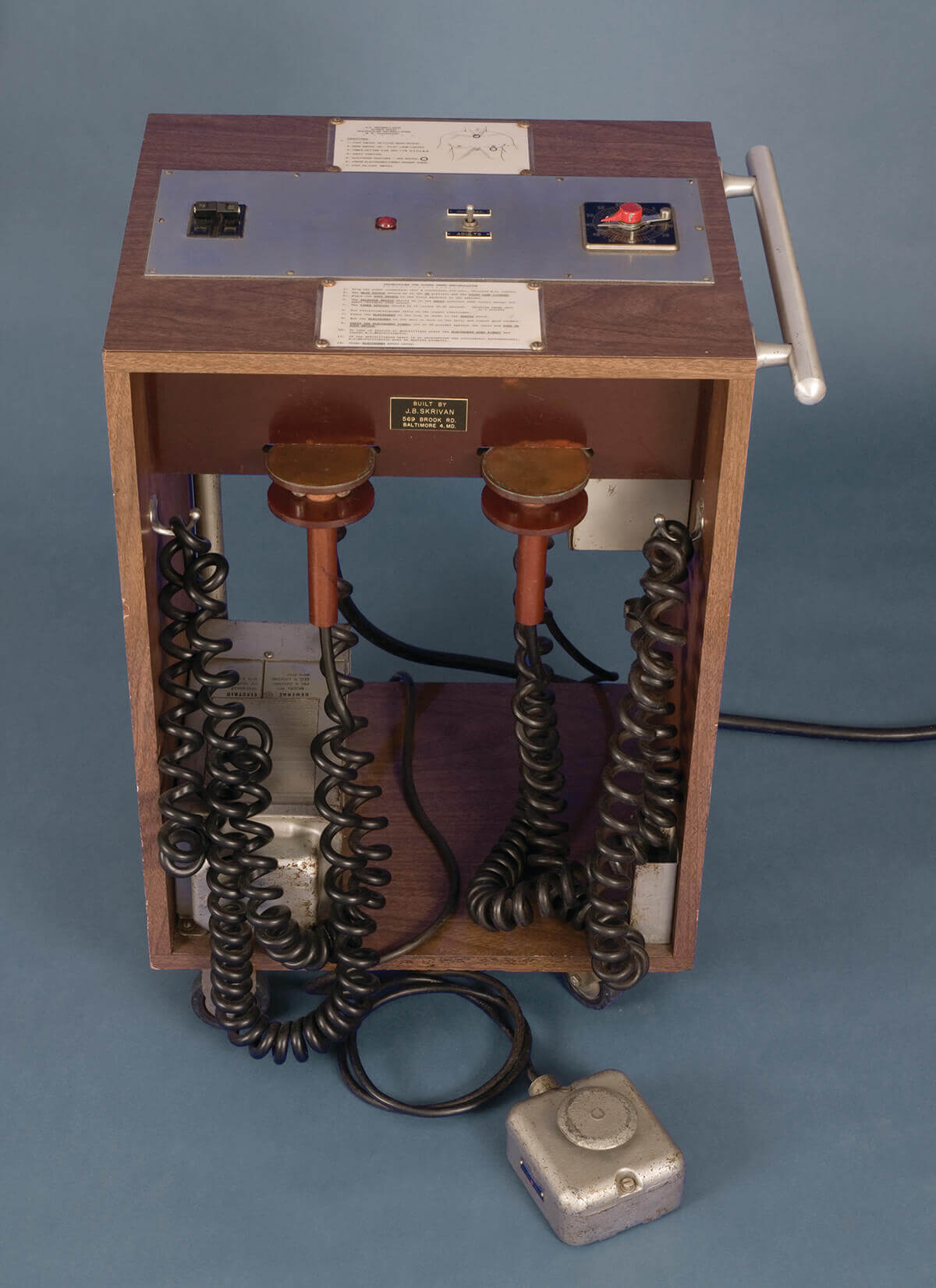

Sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) is the third leading cause of death in the United States. Approximately 356,000 people of all ages experience out-of-hospital SCA each year and nine out of 10 victims die, according to the Sudden Cardiac Arrest Foundation. When bystanders intervene immediately by giving CPR, survival rates double or triple. Nine of 10 cardiac arrest victims who receive a shock from an AED within five minutes will live.

Peter Laake is one of them. In 2021, he was a 16-year-old freshman on the Loyola Blakefield lacrosse team when the ball hit him in the chest. Like Hamlin, he experienced commotio cordis, a rare event that can occur when something strikes the chest and disrupts an otherwise healthy heart’s electrical system between beats. Like Hamlin, he went into cardiac arrest and was saved thanks to CPR and an AED.

Laake, Hamlin, and countless others have numerous people to thank, including good Samaritans who acted, skilled EMTs who treated them at the scene and transported them to hospitals, and the talented doctors who took over there. Maybe a higher power. And certainly William Kouwenhoven.

Peter Laake Was A 16-year-old High School Freshman In 2021 When He Experienced Commotio Cordis And Was Saved Using Cpr And An Aed. —Photography by Wesley LaPointe

n 1732, Scottish surgeon William Tossach used mouth-to-mouth breaths to revive a suffocated coal-pit miner in what the American Heart Association (AHA) says may be the first clinical description of mouth-tomouth resuscitation in medical literature. By the time William Kouwenhoven was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1886, manual defibrillation of the heart with an open chest was the standard last-ditch method of attempting to restart someone’s heart. Needless to say, it was a violent and invasive procedure.

Kouwenhoven did not set out specifically to change the course of medical history. He graduated with a BA in electrical engineering, and then an MS in mechanical engineering, from the Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute before earning a doctorate from the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology in Germany. In 1914, he joined the faculty of Johns Hopkins University School of Engineering, and he would stay at Hopkins for 60 years, as engineering dean, chair of electrical engineering, and as a lecturer in surgery at the Hopkins School of Medicine.

At the dawn of the 20th century, Kouwenhoven had helped wire houses in Baltimore to supplement his income. At the time, for all the advances that had been made, utility workers stringing together electric lines who received even small jolts of electricity were dying of ventricular fibrillation, when the heart is knocked off its rhythm and unable to pump blood. In 1925, utility company Consolidated Edison of New York (ConEd) commissioned the Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health to study the impact of electricity on the human body. Kouwenhoven, along with a few Hopkins doctors, joined the team working on the project.

According to a National EMS Museum timeline, “The first investigations were done on rats in 1928. They found that high voltage shocks from electrodes placed on the head and one extremity would stop breathing and the heart from pumping. By 1933, their work on dogs showed that an alternating electrical current applied directly to the heart could restore the heartbeat, but this method required opening the dog’s chest.”

That same year, the group accidentally discovered that pressure on a dog’s sternum provided adequate circulation to the brain to keep the animal alive until manual defibrillation could restart its heart. Those results were later confirmed in more than 100 dogs.

Over the course of the next 15 years (with one break when he shifted his research focus to help the American effort during World War II), Kouwenhoven and the team applied its defibrillation discovery to open-chest cardiac resuscitation, including on a human in 1947. Still, according to a 2002 story in JHU Engineering magazine, Kouwenhoven was not satisfied.

“Electrical linemen were still dying from electric shocks, and what could be done to save them?” the article quotes him as saying. “Even if a surgeon could be assigned to every line truck, the opening of the chest is still a major operation that should be performed only in a hospital.”

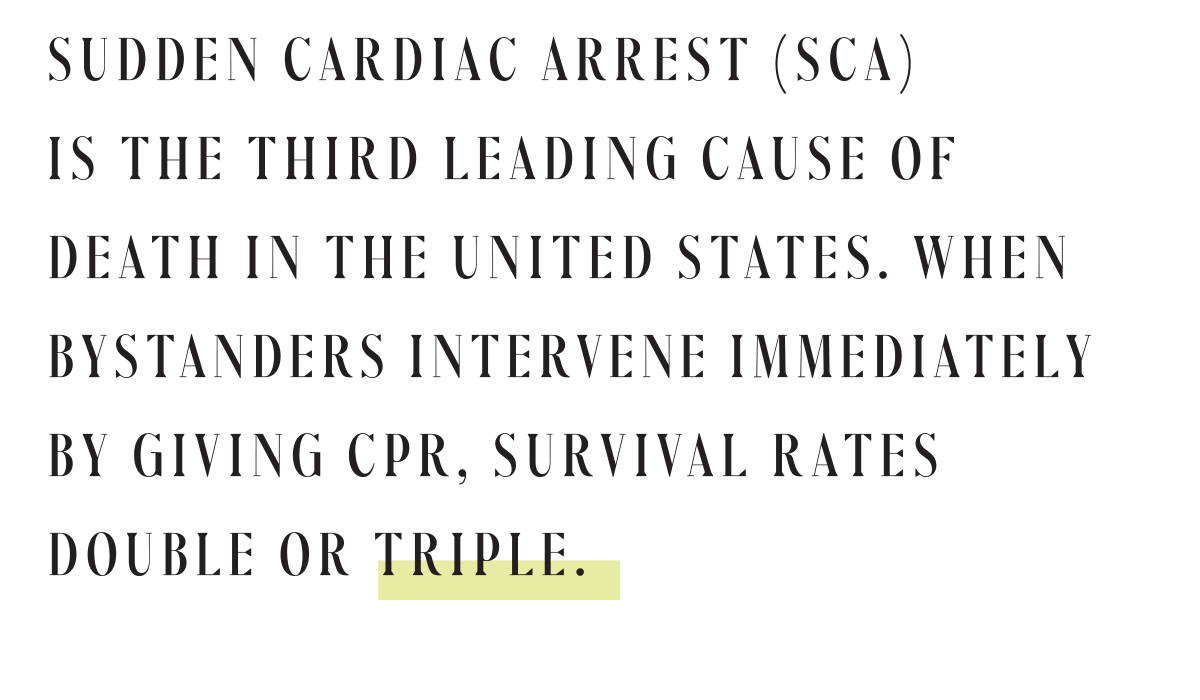

It would take another decade before he and Guy Knickerbocker, a PhD, unveiled the first portable external defibrillator in 1957. The 200-pound Hopkins Closed Chest Defibrillator was transported on a wheeled cart. Dr. James Jude, a thoracic surgeon, joined the team a year after they unveiled the machine to work on CPR.

“There’s a famous story about what happened before it got officially approved,” says Nick Kouwenhoven, his grandson. “Everybody knew he had the defibrillator at Hopkins. Somebody died in surgery, and they said, ‘Go get Kouwenhoven’s defibrillator.’ And they literally had some guy go down in an elevator. It took like 10 minutes, and they brought the thing in, and they put it on the guy. They shocked him and he came back to life. He lived another 30 years.”

Around this time, Kouwenhoven, Jude, and Dr. Peter Safar (an Austrian doctor who was working at Baltimore City Hospital) combined mouth-to-mouth breathing with chest compressions to create cardiopulmonary resuscitation, better known as CPR. (Guidelines no longer require mouth-to-mouth breathing in all cases. Hands-only CPR is recommended for use by people who see a teen or adult suddenly collapse in an out-of-hospital setting.)

“What Jude, Kouwenhoven, and Knickerbocker did in Baltimore was to treat patients who had cardiac arrest with CPR and defibrillation, and they had a remarkable survival rate,” says Dr. Myron L. “Mike” Weisfeldt, a member of the Hopkins faculty and past president of the AHA. “They published their results relatively quickly in the Journal of the American Medical Association and that led to the American Heart Association and the American Red Cross taking on the job of trying to train and advocate for the public to learn how to do CPR.”

To honor his contributions to the world of cardiology, Kouwenhoven received the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine’s first honorary Doctor of Medicine in 1969. He received many other citations, including a Scientific Achievement Award from the American Medical Association in 1972 and the Albert Lasker Clinical Research Award in 1973.

A Prototype For The World’s First Portable External Defibrillator Developed By Kouwenhoven And His Team In 1957. —Courtesy of The Chesney Archives of Johns Hopkins Medicine, Nursing, and Public Health

“My grandfather and Knickerbocker and Jude did a barnstorming tour across the country that was sponsored by the American Heart Association,” Nick says. “They trained first responders and laypeople how to perform CPR. The Heart Association also made a CPR video that my grandfather narrated. When I was at Calvert School, the teachers were like, ‘Here’s Nick’s grandfather, and here’s how you press on Resusci Annie [the life-sized mannequin once used for training CPR].’ As Jude said at the time, ‘Anyone can do this if they have two hands.’”

When William Kouwenhoven died in 1975 at the age of 89, his New York Times obituary noted that he “helped develop basic cardiac treatment devices and procedures used around the world.”

While he understood the importance of his work, he had no way of knowing how ubiquitous CPR and AEDs would become, says Nick.

“When I was a kid, some people were like, ‘Geez, you must be a billionaire because your grandfather invented the defibrillator,’” says Nick, who donated the eight-page paper detailing the chronology of his grandfather’s work to Hopkins’ medical archives. “But he didn’t patent the defibrillator. He gave it to medicine. And that was true to the time, but it was also the right thing to do.”

Guy Knickerbocker, Left, With Medical Personnel Demonstrates Closed Chest Massage On A Medical Student.—COURTESY OF THE CHESNEY ARCHIVES OF JOHNS HOPKINS MEDICINE, NURSING, AND PUBLIC HEALTH

he last thing Breanna Sudano remembers from that day more than a decade ago was going to math class. She was a 13-year-old freshman at Perry Hall High School and everything she knows now about the JV field hockey game against Catonsville she learned from someone else.

“I like to give myself a little flex point—I had scored the winning goal of the game prior to collapsing,” she says. “They said right after I scored I went to walk to the sideline and I collapsed and went into cardiac arrest. And it was at that point that the JV coach of Catonsville and the varsity coach of Perry Hall recognized what was happening and they immediately began CPR on me.”

There were also four nurses in the stands that day who rushed onto the field and assisted with CPR. Thanks to the fresh rotation of people applying compressions to her chest, she suffered no brain or organ damage. Eventually, an AED was located and shocked Sudano’s heart, restoring her heartbeat. Doctors later discovered that she had a congenital heart defect. Surgery has subsequently repaired it and Sudano, now 26, lives an active, normal life.

While still in high school, she became an advocate for CPR and AEDs, testifying in Annapolis in support of a bill that requires Maryland school districts to teach a onetime class on hands-only CPR.

The measure, enacted in 2015, is commonly known as Breanna’s Law.

“I still get goosebumps when I hear stories about people learning my law in school and then going out and saving someone’s life,” Sudano says. “Even though the law is named after me, I owe it all to the individuals who performed CPR on me. Because even though I am the survivor, the big story here is the individuals who actually perform the CPR. So, if I could share the law with those individuals and put their names on it too, I absolutely would.”

Peter Laake’s experience was different. He was playing lacrosse for Loyola Blakefield when, during a game in Towson, he tried to stop a four-on-three break and took a fast-moving shot off the chest.

“It didn’t feel like anything,” he says. “I had been hit with the ball before and just kept playing. So it just kind of felt like it was going to bruise the next day. And then I took a couple of steps and started to feel dizzy. And then within like a second, I started to feel really, really dizzy. And then everything goes blank.”

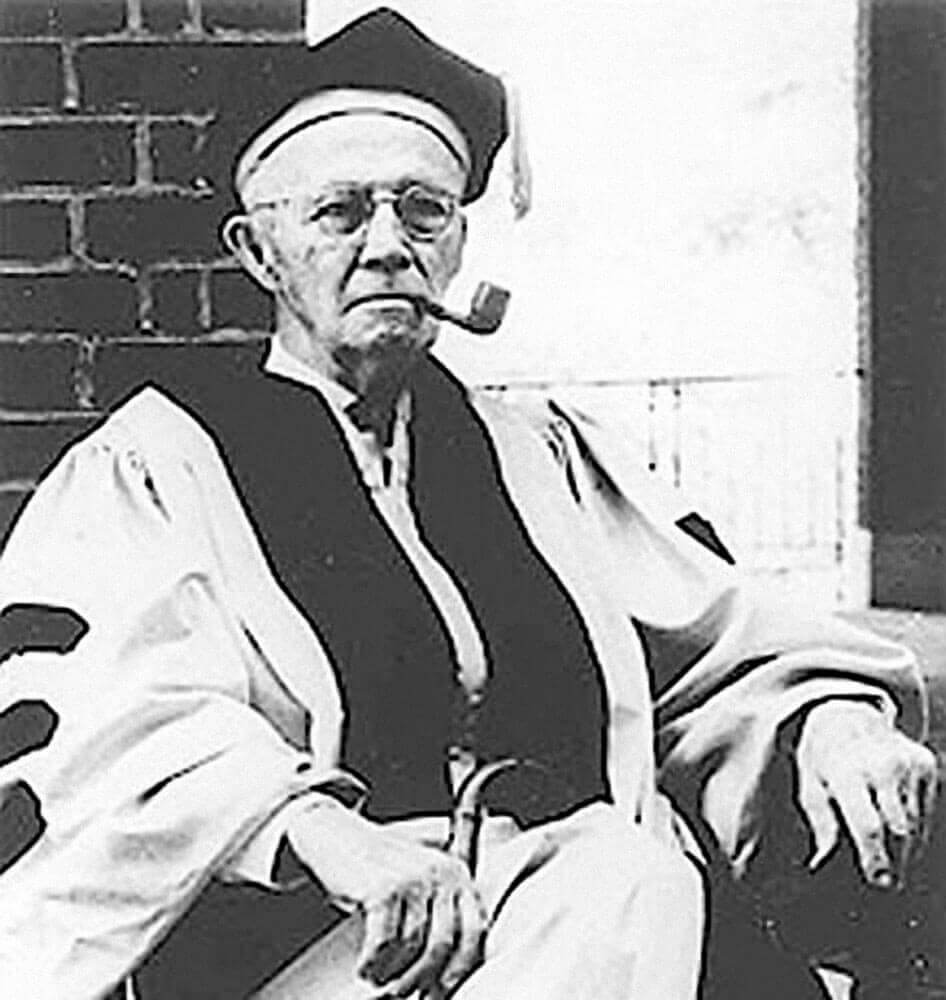

WILLIAM KOUWENHOVEN HOLDS DEFIBRILLATOR PADDLES OVER A RESEARCH DOG TO APPLY ELECTRICAL SHOCK. —Courtesy of The Chesney Archives of Johns Hopkins Medicine, Nursing, and Public Health ”

His parents, Pete and Carron, were in the stands, and immediately knew something was seriously wrong. Carron saw his legs flop into the air. Pete noticed that he fell face first without trying to brace himself.

Within seconds, the team’s athletic trainer, a doctor on the sidelines, a doctor who was in the stands, and others rushed to him. CPR was started almost immediately. An AED was quickly retrieved from the sideline and, after one shock, Laake was revived.

“All of a sudden, Peter’s head just comes whipping up off the ground,” his father recalls. “I watched his eyes roll back and he tried to sit up, and everybody’s like, ‘Hold tight.’ He started breathing rapidly because he was filling up his lungs with oxygen.”

The staff asked Laake a series of questions, including who his team was playing and what the score was. Remarkably, he got them all right. He was transported to a local hospital, where he underwent tests. The final diagnosis was commotio cordis, the same condition that afflicted Damar Hamlin. Laake was cleared to resume his career and returned to the field three weeks later. This fall, he will play lacrosse for the University of Maryland.

“If this happens and there isn’t an AED on the sidelines, it’s a different outcome,” Pete says. Tragically, that was the case at The John Carroll School in Bel Air on May 12, 2021. Bailey Bullock was a vibrant 16-year-old high school sophomore who played football, basketball, ran track, and volunteered at the local Humane Society and an assisted living facility. He was tall and thin. “All arms and legs,” says his mom, Patrice.

On that spring day, he had finished a 100-meter race when, while waiting for a ride home, he slumped over. For a litany of reasons, Patrice says, CPR was not administered for eight to nine minutes, and no AED was present. A person’s chance of survival while waiting for emergency medical services during a cardiac emergency decreases by 10 percent every minute without CPR, according to the AHA. Bailey died later that day.

Losing him was gut-wrenching, but Patrice has kept his memory alive by starting Bailey’s Heart and Soul Foundation, which raises awareness of CPR and donates AEDs to schools, churches, and other organizations. So far it has taught at least 900 people how to perform bystander hands-only CPR.

“We do fire drills. We do active shooter drills in the school systems. But I don’t hear anyone talking about a CPR drill if someone goes into sudden cardiac arrest. How do we respond?” she says. “Always have CPR in your back pocket. You never know when you will need to pull it out and utilize it. The life that you save may be that of your loved one.”

Buffalo Bills Safety Damar Hamlin Collided With A Cincinnati Bengals Wide Receiver Just Moments Before Going Into Cardiac Arrest During A Game On Jan. 2, 2023. His Heartbeat Was Restored By Medical Staff On The Field.—AP IMAGES

wice a year, something catastrophic happens to a Baltimore Raven. The team’s chief medical officer, Dr. Andrew Tucker, and his staff need to be ready for anything, so at the Under Armour Performance Center in Owings Mills during the offseason and again during the preseason at M&T Bank Stadium, they run through an emergency action plan drill. The scenarios include a player who has suffered chest trauma, abdominal trauma, cardiac arrest, heat illness, head injury, and neck injury.

The Ravens did not change their protocols following the Hamlin incident, but Tucker followed it closely, nonetheless.

“Throughout the year if we hear or see something that happened with another team or at a college, it offers an opportunity for us to sit down and say, ‘What did you see?’” he says. “‘What did they do well? What might we have done differently?’”

Since the Hamlin incident, the drills have taken on a different tone.

“You never know when lightning will strike and it’ll happen to us,” Tucker says. “You’re serious every time you do this drill, but I think it did sort of sharpen the focus. And I would like to think it happened to a lot of medical staffs that take care of athletes at all different levels.”

Each NFL team is required to submit its emergency action plan to the league and the NFL Players Association 92 to be vetted by experts, reviewed, approved, and then practiced, says Jeff Miller, executive vice president at the NFL who oversees health and safety.

Beginning in 2017, the league instituted what it calls the 60-minute meeting, which is a conference with the head referee, doctors, trainers, and unaffiliated medical staff and emergency responders an hour before each game. The point is to identify who would be responsible for what in emergency situations like the one with Hamlin.

“The nature of Damar Hamlin’s incident, a sudden cardiac arrest, doesn’t happen with any frequency, but those sorts of things are practiced nevertheless,” Miller says. “And so those protocols have been in place for a number of years and practiced for a number of years.”

The only minor change the NFL made to its protocols was instituting an additional meeting 90 minutes before each game during which medical equipment is tested. The real impact of the Hamlin incident wasn’t in the NFL, where the top physicians, trainers, and equipment are commonplace, but in youth sports.

In those lower levels, Miller explains, there isn’t the same sort of emergency action planning and uniformity of approach that is present in the pros—in some cases, they don’t even have the necessary equipment. “We as a league and many of our medical staffs are trying to take advantage of the attention that’s been paid [after the Hamlin incident] to educate more people about the necessity of AEDs and understanding of sudden cardiac arrest and the need for emergency action planning at the high school level,” he says.

In March, the NFL announced the formation of The Smart Heart Sports Coalition, which includes all the major professional sports leagues. It advocates for all 50 states to adopt evidence-based policies that will prevent fatal outcomes from sudden cardiac arrest among high school students. Each year in the U.S., SCA occurs in 7,000 to 23,000 youth under 18, making it the leading cause of death for student-athletes. The goal is threefold: For each state to require emergency action plans for each high school athletic venue that are widely distributed, posted, rehearsed, and updated annually. For there to be clearly marked AEDs at each athletic venue or within three minutes of where high school practices or competitions are held. And for coaches to be educated in CPR and AED. According to the coalition, only nine states currently require all three. (Maryland is missing the policy requiring CPR education for coaches, according to the NFL.)

WILLIAM KOUWENHOVEN WAS A HOPKINS ELECTRICAL ENGINEER AND IS KNOWN AS “THE FATHER OF CPR.” —Photography by A. Aubrey Bodine

In June, the Ravens hosted 70 people in Owings Mills for a CPR/AED education event. Three months later, the team donated 30 CPR kits to the Baltimore County Public Library. Each kit has inflatable dummies, a video on CPR, and other instructional information.

“It’s got pretty much everything needed for you to be able to learn CPR on your own and practice it at home,” says Heather Darney, the Ravens’ vice president of community relations. “It was certainly front and center with Damar and the horrific event that happened, but that can happen on the high school level. That can happen in other sports. So for us, it’s just about sharing information.”

Breanna Sudano, Peter Laake, and Patrice Bullock know firsthand the importance of what William Kouwenhoven helped create more than a half century ago. It’s as relevant today as it’s ever been.

“CPR and the defibrillator essentially put lifesaving techniques in the hands of laypeople, and I am sure he would be remarkably proud of that,” his grandson Nick says. “When they are in the hands of experts, like we saw on the football field last year, it can be even more extraordinary.”