Health & Wellness

The Existential Medicine

Decades after psychedelic drugs were outlawed, Johns Hopkins trials are revealing their dramatic therapeutic potential.

The diagnosis of Clark Martin’s liver cancer came at the same time as the birth of his daughter, with doctors informing the clinical psychologist that he likely had about a year and a half to live. “It was emotionally very upsetting,” the soft-spoken Martin recalls. “Not because of the dying, but because of my daughter.”

His late-stage cancer, however, proved one of the rare cases that responded to the initial chemotherapy. “I was lucky,” he says. But not out of the woods. During the next two decades, cancer cells would reappear in his lungs, metastasizing into tumors. On each occasion, Martin battled the disease into remission, but the endless regimens and surgeries and ever-looming threat of cancer drove him into bouts of anxiety and depression as he obsessed over his health and micro-managed his treatment plans. “I have a scientific background and became very narrowly focused,” he says. “I felt like I needed to know more than the doctors. I withdrew from life.”

Ultimately, his friends and daughter—entering college by this time—convinced him that he needed to address his mental wellbeing. He tried counseling, but it didn’t improve his outlook. Neither did antidepressants. Partly from desperation to “pop out” of his funk and partly out of professional curiosity, the Vancouver, WA-based Martin flew to Baltimore to participate in a clinical trial at Johns Hopkins where he would ingest a powerful dose of psilocybin—the naturally occurring psychoactive ingredient found in “magic” mushrooms.

After several screening and counseling visits, Martin found himself sitting on a couch in a converted medical office/living room on Hopkins’ Bayview campus. Surrounded by a statue of the Buddha, abstract expressionist paintings, soft table lamps—he lifted a blue capsule of synthetic psilocybin from a handmade Mexican chalice and placed it in his mouth. He pulled on eyeshades and laid back, listening to classical music on headphones as two clinical guides suggested he relax and focus his attention inward.

“All of a sudden, things in the room, things you feel inside, start feeling unfamiliar. Like my brain was going offline,” Martin says. “The experience in my head was just of being in a void,” he continues. “I’m a boater and I’ll use this analogy: Imagine you fall off a sailboat into the open ocean and when you turn around, the boat is gone. And then the water’s gone. And then you’re gone.

“At one point, though, I was in a stadium-like building with stained glass—it may have been a giant cathedral. At another point I had the feeling of living on a bubble. I had my space on the bubble and other people had theirs. But mostly there was just an experience of tranquility,” Martin continues. “No people, no architecture, no thoughts, no ideas—nothing. Just calm presence.”

Today, six years later, Martin credits psilocybin—as well as the preparation and guidance that went with it—with parting the fog of his depression. He also credits his psychedelic session with transforming and opening his relationships with his daughter, friends, and even his Alzheimer’s suffering father. “I still think about it every day,” he says, choking up for a moment. “I’m still unpacking and integrating what I learned into my daily life.”

Martin describes his clinical “trip” with the Schedule I drug—like LSD, it was banned during the Nixon administration because it reputedly offered no medical purpose—as among the most profound spiritual experiences in his life. It turns out that this is not unusual. In fact, it puts him among the overwhelming majority of now more than 200 clinical trial subjects at Hopkins, says Roland Griffiths, professor in the departments of psychiatry and neurosciences, and the lead architect of psilocybin studies at the medical school’s Bayview campus.

“After our first few sessions, I realized we had to develop new questionnaires if we were going to capture what people were experiencing and trying to express,” Griffiths says. “I would ask people what they meant by one of the most meaningful experiences of their lives and they’d compare it afterward to the birth of their first child or the recent death of a parent. When we followed up with them at two months, and again at 14 months, it persisted.

“When we initiated the study, I hoped we would come across something interesting,” Griffiths continues, “but in all honesty, I was unprepared for these kinds of reports—especially when they proved enduring.”

Ten years ago, Hopkins researchers, led by Griffiths and Bill Richards, a 76-year-old clinical psychologist whose work with psilocybin dates back to the heady days of psychedelic research in the early ’60s, published their first paper on their new pilot studies. Cited as a landmark report by former National Institute on Drug Abuse Director Charles Schuster, the ongoing research at Hopkins—and now other universities—has begun revealing a host of potentially dramatic therapeutic applications for the ancient psychedelic used by indigenous Mexican and South American communities in religious rituals for thousands of years. Two examples: Hopkins’ initial trial with heavy smokers documented an 80 percent abstinence rate more than a year out from the subject’s session—an unheard of success rate that is roughly 2.5 times better than reported results of those taking varenicline, the active compound in Chantix, generally considered the most effective smoking cessation treatment option. In London, an Imperial College pilot study of a dozen individuals suffering from major depression for an average of 18 years—and who had previously tried at least two standard antidepressants—found that psilocybin sessions provided a reprieve from the depression in all 12 volunteers for three weeks and kept it at bay in five subjects for three months.

Meanwhile, early returns from other university studies are indicating that psilocybin has the potential to become a revolutionary tool in treating alcoholism, drug addiction, OCD, as well as anxiety and depression associated with cancer diagnoses such as Martin suffered. Other studies show psychedelic treatment could be useful therapy for ex-offenders, in terms of reducing recidivism, by reducing substance abuse and domestic violence. Researchers acknowledge it’s not exactly clear how psilocybin manages to reduce, and in some cases eliminate, depression and the fear of death, or, ironically cravings for other drugs and substances. What is known is new fMRI imaging shows one of the immediate effects of psilocybin is decreased activity in the region of the brain that involves habitual behaviors and thinking patterns (known as the default mode network) and the perception of the self—the ego, in other words. And, that throughout recorded history, transcendent mystical experiences have produced life-altering changes in human beings. Think St. Paul’s white-light conversion on the road to Damascus; the visions of the peasant girl Joan of Arc in France; Siddhartha Gautama’s awakening beneath the Bodhi tree.

Peter Hendricks, a University of Alabama at Birmingham researcher investigating the effects of psilocybin on people addicted to cocaine, has collaborated with the Hopkins’ team. He says psychedelic sessions, properly guided, can produce a kind of therapeutic “reboot.” Which doesn’t mean he diminishes the epiphany experience and cosmic consciousness that so many psilocybin trial subjects describe. “I call it the Ebenezer Scrooge moment,” Hendricks says. “Something profound happened to Ebenezer Scrooge.”

As strange—or alarming—as it may sound to some, it’s the belief of scientists at Hopkins and elsewhere that if FDA-approved Phase II and Phase III trials currently underway continue along the same trajectory, it may not be long before psilocybin is removed from its Schedule I classification. Researchers envision a future where psilocybin, which works in similar fashion as LSD—though its effects wear off in six to seven hours, as opposed to LSD’s eight to 10 hours—is legally available for physicians and licensed counselors for use in hospice, rehab, clinical care, and therapeutic settings. Griffiths and his team are quick to caution that powerful substances such as psilocybin are not appropriate for everyone by any means, and that trial subjects are carefully screened and guided through their experience. Nonetheless, their enthusiasm is hard to overstate.

“Why wouldn’t you want to use something like psilocybin that has been shown it can be administered safely, that’s not toxic or addictive, and makes that kind of impact in people’s lives?” Richards says. “Think of the number of people who die from smoking-related diseases alone each year. What’s the dangerous drug here?”

The questions Richards poses, of course, have a loaded history.

In the 1950s and 1960s, before former Harvard professor Timothy Leary became the self-anointed pied piper of psychedelics, thousands of promising psychiatric case studies involving hallucinogens, including the treatment of depression and alcoholism, were documented and widely shared. (The efficacy of LSD in treating alcoholism, in particular, received great publicity with Bill Wilson, the co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, even touting its use to occasion the “spiritual awakening” he believed was required to help recover from the disease.) Multiple international conferences were held as it was hoped psychedelic therapy could replace psychosurgery and electroconvulsive treatment. But the political backlash against the Vietnam War era counterculture led to the 1970 Controlled Substances Act, which outlawed psychedelics for recreational use and, for all intents and purposes, quashed studies into such drugs. Nixon once dubbed the happily anti-authoritarian Leary, “the most dangerous man in America.”

“For 30 years, medical and psychiatric research into psychedelics was virtually non-existent. It just went dark for non-science reasons—universities didn’t want to touch it—and for professors it looked like career suicide,” says Griffiths. “In modern times, there’s nothing else like this.”

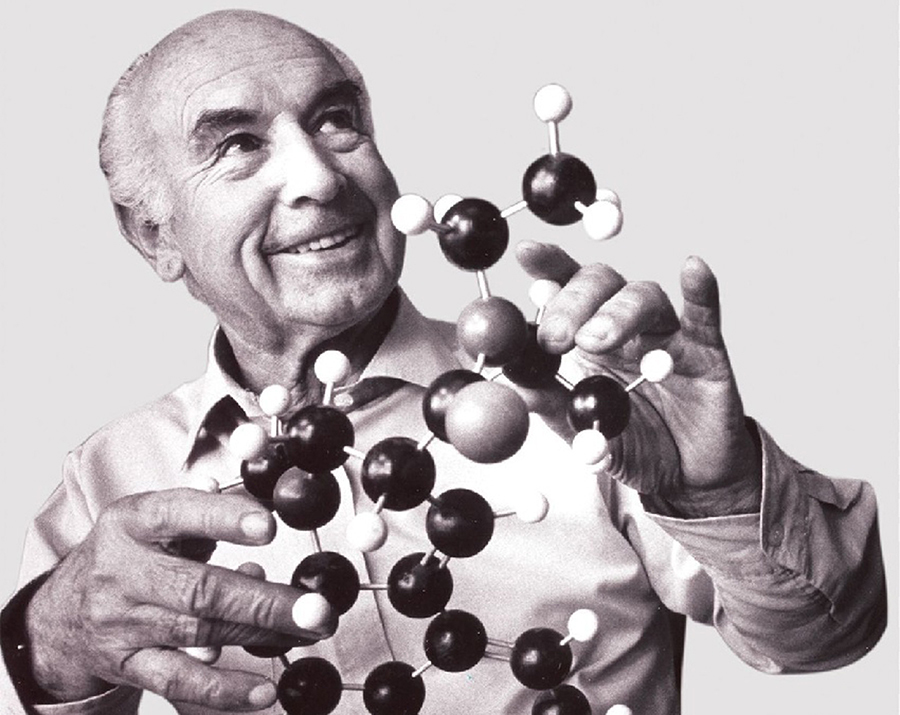

The idea that plants could possess medicinal (or in this case, existential) value wasn’t new when Swiss scientist Albert Hofmann— working with the ergot fungus, which grows in rye kernels—became the first person to synthesize lysergic acid diethylamide, aka LSD. In 1943, after accidentally absorbing the compound through his fingertips, Hofmann experienced a feeling of joyful unity with nature similar to an evocative memory of a walk in the forest that had stuck with him since childhood. A few days later, curious and naïve, Hofmann intentionally ingested a much stronger dose of LSD that altered his consciousness more dramatically—frighteningly so. In fact, it took several hours before a sense of calm and beauty emerged. (That day, April 19, later became celebrated as the first “acid” trip and “Bicycle Day” among psychedelic advocates after the scientist famously recounted riding his bike home from his lab that afternoon.)

Hofmann jotted down the vivid imagery and fantastic shapes and colors he saw and developed an intense interest in “sacred” plants, leading to expeditions to Mexico where he witnessed religious mushroom rituals. Eventually, he isolated and synthesized the hallucinogen in that fungus as well, naming it psilocybin, which a curandera, a native healer and shaman, confirmed had “the same power” as the indigenous mushrooms.

It was Hofmann’s employer, Sandoz Laboratories (pharma giant Novartis today), that later supplied mail-order psychedelics for Leary’s experiments—as well as those of another Harvard Psilocybin Studies pioneer, Walter Pahnke, a psychiatrist and minister working on a Ph.D. dissertation in Religion and Society under Leary’s supervision. Pahnke later worked with Richards in Germany and, a few years after that, joined Richards on the Spring Grove State Hospital psychiatric research team in Catonsville in the late 1960s. He died in a scuba accident in 1971, but remains renowned for conducting the Good Friday Experiment, one of the most influential psychedelic studies ever.

His groundbreaking double-blind experiment with 20 theology students took place at Boston University’s Marsh Chapel during the Good Friday service there in 1962. His hypothesis was that psilocybin could reliably—in the right setting, with spiritually inclined people—induce a religious experience similar to the direct encounters of recognized mystics such as Plotinus, Shankara, and Saint Teresa of Avila. (The Mystical Experience Questionnaire, formulated later by Pahnke and Richards, is still the basis of the survey commonly used in studies.)

In Pahnke’s experiment, half of the graduate students received psilocybin and the other half a huge dose of a Vitamin B “active” placebo that would at least create some itchy skin and flush the face. Meanwhile, the Good Friday service—including organ music and singing from the choir—was broadcast from the main sanctuary into the basement chapel where they were under supervision. Eight of the 10 divinity students receiving a capsule of psilocybin—overcome with feelings of “unity” and “eternity” for the first time—expressed their experience as an ineffable transcendence of time and space. Tears of joy streamed down the cheeks of one student; another said he seemed to be relinquishing his life “in layers,” experiencing a greater sense of “oneness” at each step. Rev. Randall Laakko, then a divinity student, initially fled the chapel when the psilocybin first induced panic and paranoia. He believed he was “in hell” until he stepped outside on that sunny spring day and walked into a suddenly transcendent experience. “Everything in the world just seemed to glow inwardly with life,” he later recounted in a BBC documentary. “It changed my life . . . That day demonstrated the reality of God’s presence in all the world.”

Six of 10 overall also felt a sense of “sacredness” during their trial trip and Pahnke concluded that the reports from the eight who received the psilocybin were “indistinguishable from, if not identical” to the classic experiences described by mystics in their own words and chronicled in William James’ seminal work, The Varieties of Religious Experience, published in 1902.

Though more rigorous and diverse, the current crop of psilocybin studies are essentially reprises of Pahnke’s dissertation study. (Griffiths has a copy in his file cabinent.) But the Good Friday Experiment also resonates today because it points to the conundrum of quantifying the psychedelic phenomenon in scientific terms. Depending on one’s view, the psilocybin trials raise questions—or confer answers—about the existence of God, the collective unconscious, the true nature of reality, chemistry, neurobiology, and quantum physics. “Little things like that,” Richards says with a chuckle in his home office near Leakin Park.

To that end, one of Hopkins’ current psilocybin projects is looking at the effects of the compound on the brains of longtime meditators via fMRI imaging. Another experiment, in partnership with New York University, is giving psilocybin to clergy from various faith traditions in an effort to examine how those in the religious community assimilate the experience into their lives and/or vocation.

Richards is deeply interested in the neuroscience, but for him, the veracity of spiritual experiences described by subjects won’t be found in brain scans. He says “the fruits” of a given subject’s experience provide the real testament. “Does it turn someone’s life in a positive direction?”

That it was Griffiths and Richards who partnered in the first successful re-launch of U.S. research into the possible psychiatric benefits of psilocybin is a bit of local serendipity. Richards, six years older than Griffiths, spent much of his early career—including a stretch from 1967-1977 at Spring Grove Hospital Center in Catonsville and the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center—doing some of the very last clinical work and research with psychedelics in the U.S. until the recent renaissance. “Maybe that’s because we were close to Washington and they could keep an eye on us,” jokes Richards, whose gentle demeanor is regularly punctuated with hearty belly laughs. “But the money for research dried up. That’s what happened everywhere. I was just the last person out the door.”

Although Richards and Griffiths had worked in the same city for decades, they’d never met until they were introduced through Bob Jesse, a former Oracle vice president who founded the Council on Spiritual Practices in the early-’90s.

(Jesse, who coincidentally grew up in Baltimore County and studied computer engineering at Hopkins, was—and remains—focused in exploring the connections between the use of psychedelics and potential spiritual and psychological benefits for healthy individuals. He notes, for example, that the Native American Church in the U.S. has had the right to use peyote in its religious rituals for several decades. And, more recently, that a U.S. sect of the Brazilian church, União do Vegetal—literally “union of the plants”—with a brief filed on its behalf by no less than the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops—challenged and got around a ban on DMT, another Schedule I substance and principle ingredient of ayahuasca tea, which is key to UDV’s rituals imported from South America. “Psychedelics should not just be available for people who need treatment,” Jesse says. “They should be available for people who want to become happy individuals as well.”)

In many ways, Richards and Griffiths backgrounds were far removed from each other for most of their careers. The image of Leary and the reputation of psychedelics, if anything, Griffiths says, probably dissuaded him from looking into psilocybin research earlier. But Griffiths’ own sense of self had shifted over the years after beginning a personal meditative practice and when he expressed interest in the psychedelic research the Council on Spiritual Practice was looking to rejuvenate and privately fund—the two-generation old stigma continues to keep a lid on public research money—Jesse knew whom he had to meet.

As a graduate student in Germany, Richards volunteered for an psilocybin experiment in 1963, which sparked a lifelong interest in psychedelic research and clinical work, as well as the psychology of religion. When he returned to the U.S., Richards soon got to know Leary—not long after Harvard had expelled the controversial professor. Among other early researchers, Richards also knew Leary’s close colleague with the infamous Harvard Psilocybin Project, former professor Richard Alpert, the spiritual teacher who wrote the 1971 best-seller on spirituality, yoga, and meditation, Be Here Now, after traveling to India where he received the Sanskrit name Ram Dass (“servant of God”) from a Hindu guru. Richards also counts 97-year-old Huston Smith—a more cautious participant in the Harvard scene and considered one of the world’s foremost comparative religion scholars—as a mentor. And Richards recently published his first book, Sacred Knowledge: Psychedelics and Religious Experiences, which draws parallels between the unitive, interconnected experience people often describe after a psilocybin session or LSD trip with the “holy” consciousness and encounters with the divine described by religious mystics across millenniums, cultures, and continents.

Griffiths, for his part, became one of the nation’s most respected researchers in the field of behavioral pharmacology, mood-altering drugs, and addiction while earning appointments at Hopkins. The author of more than 300 journal articles, his research has been largely funded by National Institutes of Health grants. He’s been a consultant to numerous pharmaceutical companies in the development of psychotropic drugs (such as those prescribed to treat depression and anxiety) and he is currently a member of the expert advisory panel on drug dependence for the World Health Organization. His sterling reputation at Hopkins and relationships with FDA officials was critical in getting various review boards to sign off on the pilot trials with psilocybin.

Tall and lean with a tussle of white hair and twinkling blue eyes, Griffiths possesses a certain professorial exterior, but also an easy affability.

“Our résumés are different,” Richards says. “But we complement each other. We make a good team.”

Dan Kreitman, a 55-year-old upholsterer and smoker for nearly 40 years, is one of the Hopkins’ psychedelic studies living proofs. Grabbing a chair in his workshop in his Baltimore County garage, the gregarious Kreitman recounts his psilocybin sessions that were a part of the smoking cessation trials. “Three years later, I’m totally amazed by it,” he says, taking a break on a warm Saturday afternoon. “Bringing it up, I remember how good it was—and all the positive feelings come right back.

“I’m going to warn you,” adds Kreitman. “When I talk about it, I can get emotional.”

Kreitman not only wanted to quit smoking for years without success, he’d become ashamed of his habit—sneaking cigarettes when his son, daughter, and wife weren’t around. Given his age, that he didn’t eat great and was overweight, his family also pressed him to quit. “It was my son, who was 18 then, who heard about the Hopkins’s studies and told me.” As part of his preparation, Kreitman was asked to keep a smoking diary—writing down the times of day when he picked up a cigarette. He also went through about six to eight counseling sessions, which included guided meditation exercises in the run-up before receiving his “magic” blue capsules of psilocybin.

Kreitman actually took three capsules of psilocybin in three separate sessions, in progressively stronger doses, he believes. The first session was very positive. “My father had recently committed suicide, but no demons or dragons,” he says. “Happy thoughts.”

The second experience was more of everything. “More vivid colors, more crazy shapes.” More happy thoughts.

“The third session, I left Earth and saw infinity,” Kreitman says. “It was so intense, so holy, I don’t know how to talk about it. A lot of stars, planets, a lot of the cosmos. It was so colorful and beautiful—I’m still blown away.

“And I saw my dad,” he continues. “He was in a boat floating down a river and he smiled and waved. I also saw an image of an old rabbi, somebody who looked like the God of the Old Testament with the white beard—the image of God I grew up with—steering the boat.”

The overwhelming feeling, Kreitman says, was of going out into the universe. Although he wasn’t sure if he’d be coming back or not. “It didn’t matter,” he says, wiping the corner of his eye. “Everything was okay.”

Smokers are considered good test cases in terms of addiction because their lives are often less chaotic and they have suffered fewer acute consequences than say, a heroin addict, says Matt Johnson, a Johns Hopkins associate professor of psychiatry and lead author of the smoking cessation study. Nonetheless, adds Johnson, cigarette addiction and dependence on other substances usually involves more than physical cravings. There’s a social dynamic when two or more smokers gather. There’s also a repetitive ritualistic component that can serve as an emotional crutch throughout the day.

Both addiction and depression create a sort of self-perpetuating tunneling of the brain’s default mode network—a downward spiraling in thinking patterns and behavior—that only burrows over time. Psilocybin, on the other hand, Johnson says, generates “a whole lot more cross-talk across the brain,” which can have the effect of breaking apart these tunnels and dramatically shifting a subject’s perspective. “All of a sudden people go from talking about the strange colors they’re seeing to talking about a communion with a higher power, who some call God,” he says. “It’s this insight they experience that provides a new, ‘big picture.’ It becomes a spiritual guidepost and stays with them. They realize, ‘I’m a miracle. I can quit smoking.’”

Kreitman describes himself today as more in rhythm with people, and with the world around him. “If I’m getting off the train and someone drops something,” he says, “it’s like I’m immediately aware this person needs help and I’m bending over to help them.” He’s also more open to new things. His appreciation of music, which he’s always loved, has deepened.

Whenever he feels the smallest funk coming on, he says, all he has to do is put on a CD of Aaron Copland’s “Appalachian Spring,” which he listened to during his third session.

He’s also eating better and has lost 15-20 pounds. He’s down to about 180 pounds now on his 5-foot-7 frame. “But I still grab some fried chicken on the weekend when I get a chance,” he chuckles. He’s also going to synagogue more, but adds with a smile that it might be because his cousin who goes regularly lives closer to him than in the past.

He says that he used to picture himself at 70, sitting on the porch with emphysema—a can of beer in hand. “Now, a whole new chapter of my life has opened up that I never expected,” Kreitman says. “Is that a religious experience? If not, I don’t know what is.”

As far as the smoking goes, he put out his last Camel on the drive to the Bayview clinic before his final psilocybin session. “I don’t feel like an ex-smoker,” Kreitman says. “I feel like a non-smoker—like I was never a smoker. My wife and I will be outside Giant or someplace and we’ll walk past employees out front smoking and I’ll catch myself saying to her, ‘They shouldn’t let people stand near the doors and smoke like that.’

“She just laughs at me.”

Update: This article has been updated to contain a sponsored link from treatment4addiction.com.