Health & Wellness

Pot Luck

Medical cannabis rolls out in Maryland, but there's a catch.

As if it were yesterday, Shannon Moore remembers the moment two years ago when a neurologist asked her and her husband, Louis Deliyannis, if they wanted hospice care for their identical twin boys, who were then 3 years old. The boys, Nicolas and Byron, were born with Miller-Dieker syndrome, which causes them to have severe seizures all day, every day.

“When the neurologist said it was time to choose between length and quality of life, we considered medical cannabis,” says Moore, 42. “I knew other parents had successfully used it to treat their children’s seizures.”

But since it wasn’t available in Maryland, they had to use legal hemp oil instead, giving it to the boys through their feeding tubes. It was a stopgap measure, since it has some of the therapeutic qualities that cannabis does. Nevertheless, within days, the frequency and severity of the twins’ seizures decreased by more than half.

“I believe it saved their lives,” says Moore of her boys. “And because it did, I became very driven to make sure that others could be treated with cannabis, which will give us more options.”

In the very near future, those new treatment options will be available to patients like Nicolas and Byron when the state rolls out its medical cannabis program.

But it’s not the panacea it might seem for patients like Moore’s boys: The implications of the new legislation are complicated and imperfect because of discrepancies in federal and state laws—and because of widespread misconceptions about the medical variety of marijuana.

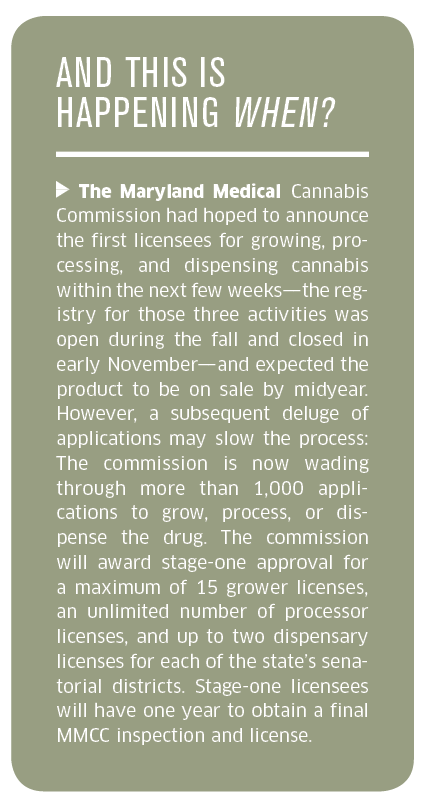

Maryland’s not exactly leading the charge in legalizing medical marijuana. The first time sanctioning cannabis was suggested in Maryland was 1979, but it took years for the cultural zeitgeist to get to a point where the state legislature was ready to join the 18 states (plus the District of Columbia) that have legalized medical marijuana since 2013. That same year, Maryland made cannabis available to teaching hospitals, though none participated. But public opinion backed yet more change: A spring 2014 Goucher College poll showed that 90 percent of Marylanders support the use of the drug for medical purposes, and more legislation passed with bipartisan support last summer.

“Medical cannabis got caught up in the epic war on drugs,” says Del. Dan Morhaim of the 11th District in Baltimore County, an emergency-medicine physician who sponsored the initial bill. “What I’m saying is, let’s remove the sick and the dying from the battlefield.”

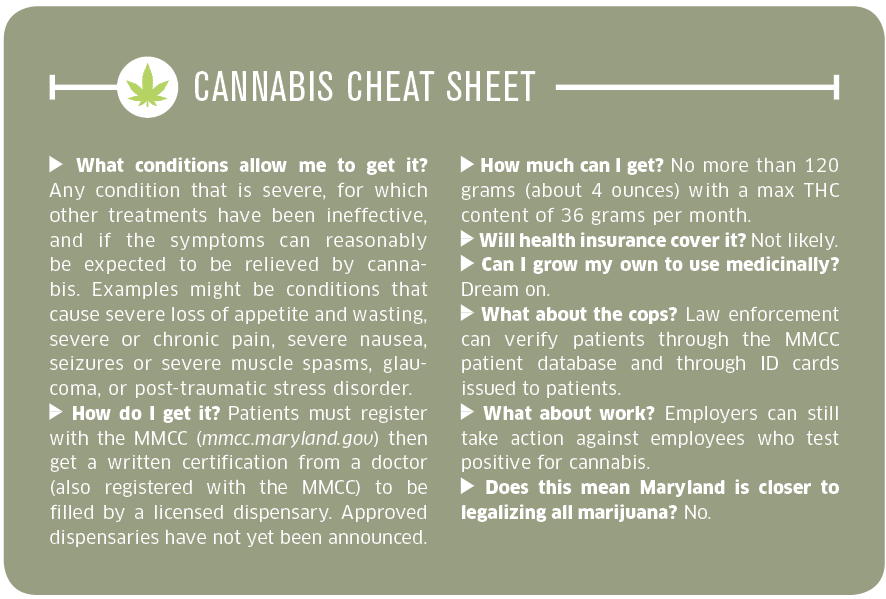

The complicated part of the new law is that medical cannabis is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration and the federal government still classifies marijuana as a Schedule I drug, the classification reserved for the most dangerous drugs, including heroin.

As a work-around, the U.S. Department of Justice has told federal prosecutors they can’t go after patients and doctors in states where medical cannabis is legal.

That, of course, leaves a lot of a weird middle ground. Doctors can’t be prosecuted for giving you a recommendation for marijuana to alleviate your multiple sclerosis, for example, but you can still get fired from your job if you come up positive in a drug test.

“Medical cannabis got caught up in the epic war on drugs. Let’s remove the sick from the battlefield.”

Hannah Byron, the outgoing executive director of the Maryland Medical Cannabis Commission (MMCC)—of which Shannon Moore is a member—says that other states are looking at Maryland as a model for their own laws. Among the Maryland law’s stipulations, for instance, are quality controls to make sure medical cannabis is free of substances such as mold, which can be life-threatening to the immune-suppressed.

Byron, a former administrator at the Department of Business and Economic Development, says anyone who is concerned that Maryland is suddenly going to look like Amsterdam on a holiday weekend doesn’t understand what medical cannabis is—and isn’t.

“The way the medicine can be given includes tinctures, oils, patches, suppositories—people want to see alternatives to smoking,” says Byron. She notes that different strains of the plant serve different purposes. The medication for seizures, for example, is low in tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC, marijuana’s active ingredient and the part of the plant that makes you high.

Byron abhors when people use slang like “pot,” and is no-nonsense about the measures the MMCC—which has 16 voluntary members including a police chief, lawyers, a horticulturalist, and doctors—will follow in registering patients and doctors as well as managing licensing, community education, and data reporting. She notes that there are extreme penalties (a $10,000 fine) for diverting medical cannabis. And honestly, if you just want to get high, there are easier ways.

“If someone is really interested in using cannabis for recreational purposes, they’re not going to go through everything you need to go through to get medical cannabis,” says Byron.

Cannabis will have an economic impact. In 2014, Arizona’s medical cannabis market was worth an estimated $155 million, with those numbers in 2015 projected to reach $207 million. Maryland could experience something similar.

Cannabis will have an economic impact. In 2014, Arizona’s medical cannabis market was worth an estimated $155 million, with those numbers in 2015 projected to reach $207 million. Maryland could experience something similar.

“We’re building an entire, homegrown industry that encompasses agriculture, manufacturing, and retail,” Byron says.

Unsurprisingly, entrepreneurs have already jumped into the game to get their slice of the economic trickle-down. Green Leaf Medical, a prospective grower and processor based in Gaithersburg, leased 42,000 square feet of warehouse space last year where it hopes to grow at least 5,000 plants. The company CEO, Philip Goldberg, a local businessman, says Green Leaf’s climate-controlled operation can bring in three or four harvests a year, with each plant providing at least half a pound of dry cannabis. Ambitious local teenagers can abandon hope of getting inside, though. Goldberg says the walls are tilt-up concrete and security includes more than 140 cameras.

“It takes 24 hours to get a guest pass so we can vet you, and, without a badge, you aren’t getting inside,” he says. “We don’t sell retail, so it would be suspicious for anyone to be there. You wouldn’t make it past the gate.”

Proponents point out that cannabis has proven helpful to many, from cancer patients and people with conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis to those with epilepsy. It’s also used for the palliative care of those in hospice. Critics of medical cannabis say there’s not enough research showing its efficacy in disease treatment. And they’re both right.

Because of its classification as a Schedule I drug, research into cannabis has been somewhat restricted. Advocacy groups such as the Epilepsy Foundation are actively working to reclassify marijuana so more studies can be done.

“Of course, there are risks and side effects as we see with many drugs we currently prescribe,” says Morhaim. But marijuana overdose deaths are extremely rare: A recent study claimed to have identified two such cases. In addition, legal medical cannabis could help reduce overdoses using other drugs: The Journal of the American Medical Association reported in 2014 that states with medical cannabis laws saw a 25 percent drop in opioid overdose deaths compared to states where cannabis is still illegal. Such a drop would be good news in Maryland, where the painkiller fentanyl was implicated in 185 deaths in 2014 alone, more than three times as many as the year before.

That’s why Shannon Moore can’t wait to try cannabis instead of the drugs she’s been using as a rescue medication to stop her twins’ extreme seizures. The cannabis is said to help control such episodes without the risks posed by Benzodiazepines (BZD) opioids, which can be addictive and cause respiratory depression.

“I used to think medical cannabis was a joke,” says Moore. “Now, I feel very grateful for it, and I want to make sure others can work through their doctors and have safe access to it as medicine.”