Some swear by homeopathy, but skeptics of this 200-year-old mode of treatment abound.

Home & Living

Medicine or Myth?

Some swear by homeopathy, but skeptics of this 200-year-old mode of treatment abound

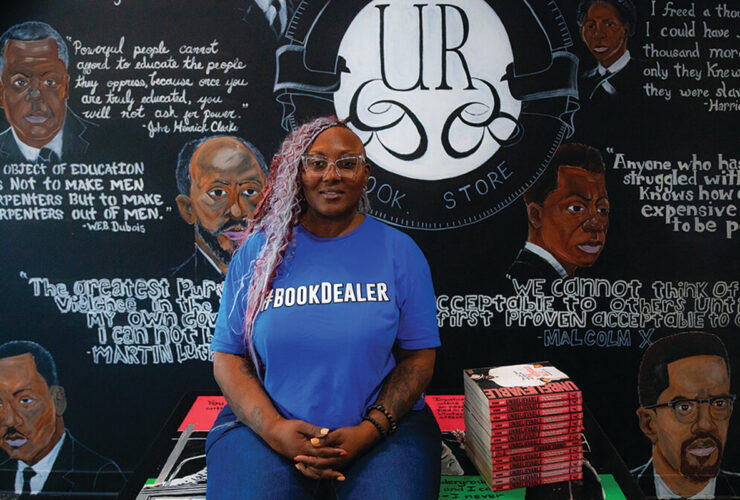

Back when he was a 30-something martial-arts enthusiast dealing with the bumps and bruises of his hobby, Bernie Simon tried the usual over-the-counter pain relievers. The results weren’t particularly satisfying, recalls Simon, now a 64-year-old computer programmer who lives in Towson. “Then I heard about homeopathic remedies made with arnica and rhus toxicodendron [poison ivy],” he says. “What I found was that it worked really much better than the conventional medicines for dealing with these kinds of problems.”

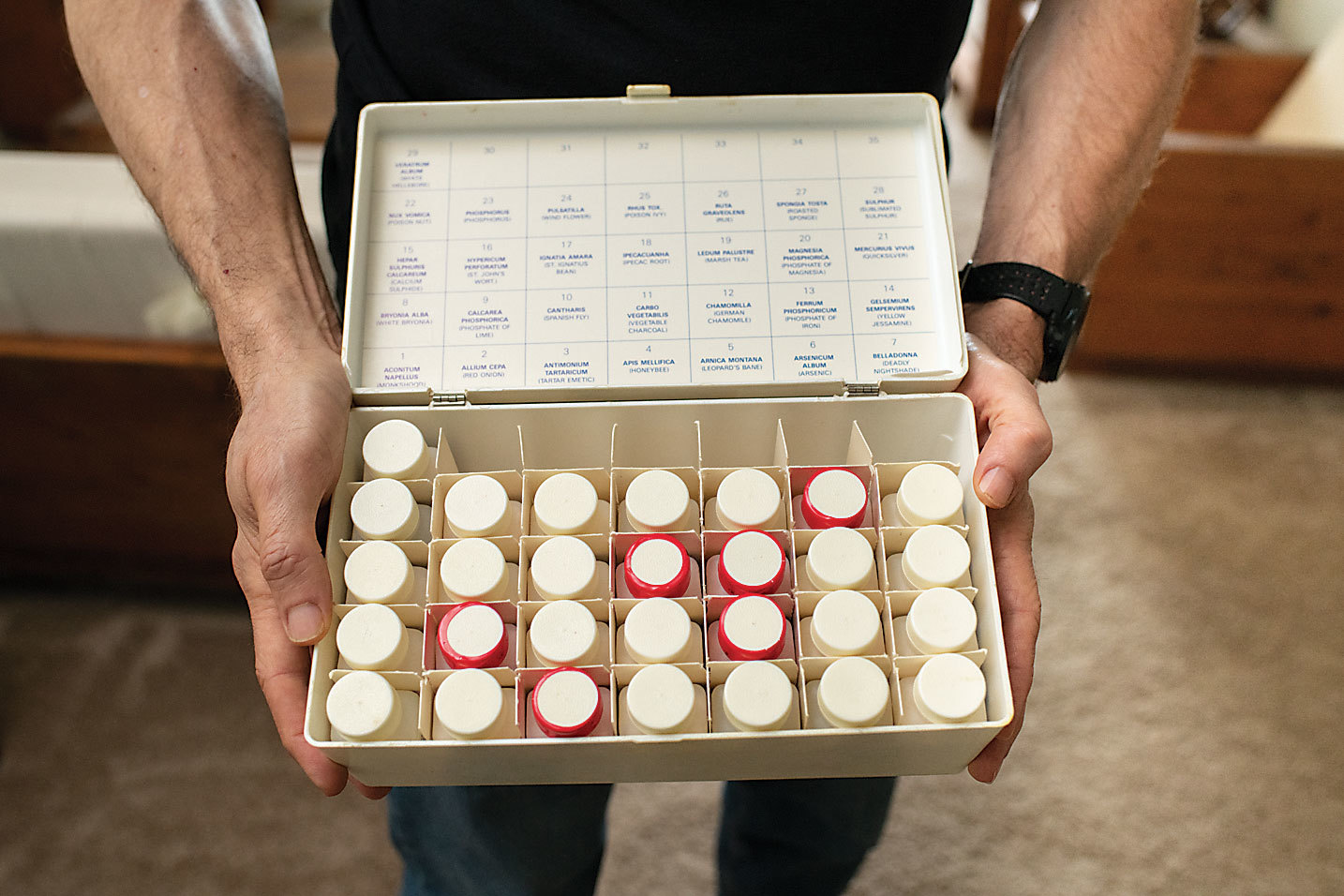

Encouraged, and armed with a self-help book and a kit from a local pharmacist who sold homeopathic remedies, Simon was soon treating himself homeopathically when various minor ailments cropped up. What he learned: “It didn’t work every time, but it worked enough times to make me convinced.”

Since then, he has been active in a study group that meets monthly to discuss homeopathy and has sought out naturopaths for homeopathic treatment of more serious chronic illnesses—such as a years-long struggle with irritable bowel syndrome.

Frustrated by more conventional treatments, Simon is among the millions of Americans who’ve turned to homeopathic medicine, either in the form of over-the-counter remedies, self-treatment, or through treatment by naturopaths, homeopaths, chiropractors, and even medical doctors and dentists who’ve embraced the 200-year-old system of medicine.

Bernie Simon has been a homeopathy believer for years and is part of a monthly homeopathy study group.

According to one analysis from the federal National Health Interview Survey conducted in 2012, the most recent year for which numbers are available, nearly six million Americans use homeopathy, typically for colds, earaches, and musculoskeletal complaints. And their spending has grown substantially in the past decade, resulting in what experts estimate is a $1 billion-plus industry.

Proponents say homeopathy provides a natural and effective path to health. Critics, meanwhile, view the practice with intense skepticism—and concern that it could be a dangerous diversion from medical treatments that are proven safe and effective.

Developed in the late 1700s by German physician C.F. Samuel Hahnemann, homeopathy is centered on the principle of “likes cure likes.”

Struck by the fact that the symptoms produced by quinine on the healthy body were similar to those of malaria—which quinine was used to cure—he concluded that a remedy that produces symptoms in a healthy person will cure those same symptoms when they’re caused by a disease. He theorized, for example, that insomnia could be cured with a remedy made from caffeine. And mainstream medicine appears to have picked up on this in a few areas, such as treating snake bites with serum made from the venom of the snake that was the culprit.

Hahnemann also believed that the less of the active ingredient it contained, the stronger the remedy was. By that logic, homeopathic remedies are highly diluted, usually in water—and agitated at each stage of dilution—until there is no detectible trace of the original substance left. They’re often given by mouth in the form of a sugar pill coated with the diluted substance, though they can also be delivered in cream or gel form, or in drops or tablets.

Consumers, he says, may incorrectly assume such remedies are proven safe and effective, simply because they’re found on pharmacy shelves.

Such remedies don’t work in the same way as conventional medicines, says Roland Park’s Emily Telfair, who holds a doctorate in naturopathic medicine. Her HeartSpace Natural Medicine practice offerings include homeopathy, botanical medicine, lifestyle counseling, nutrition, and craniosacral therapy. “I like to think of it as reminding the body of what it’s supposed to do,” she says. “It’s not the medicine, it’s the body’s reaction to it that promotes health.”

Seeing patients in a cheerily renovated former home on Falls Road, Telfair views homeopathy as a gentle, effective way to treat complaints that can range from sore throat to sleep issues, skin disorders, and anxiety, which she says often causes physical symptoms.

“If the remedy helps relieve anxiety, a lot of the physical symptoms improve,” she says.

As a naturopath—Telfair is past-president of the Maryland Naturopathic Doctors Association and was instrumental in the passage of a state law that allows naturopaths to be licensed professionals—she focuses on a whole-body approach. An initial visit lasts two hours and consists of talking with patients about their lifestyle, including their diet and activity habits, emotional state, and social situation.

“I’m really learning about who they are as a person,” says Telfair, who calls that approach one of the distinguishing pieces of naturopathic care. That homeopathic remedies vary by patient, even for the same illness, “is just one aspect of homeopathy,” she says. Such visits aren’t covered by insurance, however, and can be pricey. An initial consultation with Telfair, for example, is $340.

Not far from Telfair’s office, patients in search of homeopathic treatment have for years headed to The Ruscombe Mansion Community Health Center’s Peter Hinderberger, one of the few medical doctors locally who incorporates homeopathy into their practice. Originally from Switzerland, where he earned his medical degree, Hinderberger has been practicing homeopathy and other alternative therapies in Baltimore since 1984.

Like Telfair, Hinderberger begins with a long initial visit to delve into multiple aspects of a patient’s problem. He even asks them to bring in a written account of past illnesses or traumas. “In holistic or complementary medicine, we believe that before an illness manifests physically, there has been an imbalance in the vital force.” He describes homeopathy as “energy medicine” and says patients often seek him out when conventional medicine fails.

“Patients like that it’s non-toxic, has been around for 200 years, and most of them have had experience with homeopathy,” says Hinderberger. “Also, with children, you just take these sugar pills, and kids like that. And, especially with children, it’s very effective.”

Though homeopathic doctors and hospitals were common in the 19th century, the mainstream medical and scientific community has long distanced itself from the practice, often vocally. The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), the federal government’s lead agency for scientific research on health care that falls outside of conventional medicine, says there is “little evidence to support homeopathy as an effective treatment for any specific health condition” and that “several key concepts of homeopathy are inconsistent with fundamental concepts of chemistry and physics.” It also cautions that, while homeopathic products are supposed to be highly diluted, there have been cases where products labeled homeopathic actually contained substantial active ingredients and caused ill effects in people who took them. NCCIH also warns against using homeopathic products as a substitute for conventional immunizations. In 2015, a widely publicized Australian government review of 176 studies came to a similar conclusion about efficacy when it failed to find that homeopathic remedies offer anything greater than a placebo effect. And in recent years, the FDA and the FTC announced efforts to more closely regulate homeopathic remedies.

nearly six million Americans use homeopathy, typically for colds, earaches, and musculoskeletal complaints.

One of the more vocal critics is Steven Salzberg, a professor of biomedical engineering, computer science, and biostatistics at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. He runs a computational biology lab that develops new methods to analyze DNA and RNA sequences, but he also regularly blogs about alternative medicine and pseudoscience. Salzberg’s especially skeptical of homeopathy: “Homeopathy isn’t medicine—period,” he says.

He also points out that, unlike conventional medications, homeopathic remedies are not evaluated by the FDA for efficacy and safety (though the FDA does regulate homeopathic products in terms of allowed ingredients and certain labeling requirements). Consumers, he says, may incorrectly assume such remedies—say, eye drops for irritated eyes—are proven safe and effective, simply because they’re found on pharmacy shelves.

Of course, the homeopathic community, accustomed to criticism, has its counterarguments. The American Institute of Homeopathy (AIH), which represents medical doctors and other licensed health professionals who use homeopathy professionally, says “there are literally hundreds of basic-science, pre-clinical, and clinical studies (including very large observational studies) that show homeopathy to be an effective therapeutic intervention.” The results, it says, can’t be explained merely by the placebo effect.

Use homeopathy, typically for colds, earaches, and musculoskeletal complaints.

Proponents argue studies painting homeopathy as ineffective are flawed and that mainstream medicine is biased against it. Along with other groups, including the National Center for Homeopathy, which promotes education about and awareness of homeopathy, AIH has presented its case to the FDA, FTC, members of Congress, and the public.

Their hope is that when people learn more about homeopathy, they’ll be less critical. “What people don’t understand, they’re likely to be wary of,” says Telfair, who has for the past four years been a guest lecturer for an integrative medicine elective course offered to University of Maryland fourth-year medical students. The course, which draws 12 to 15 medical students a semester and usually has a waiting list, doesn’t focus on homeopathic medicine, but Telfair gives students a taste of both herbal medicine and homeopathy during her lectures.

Homeopathy’s proponents often present it as an adjunct to conventional medicine—hence, the use of words such as “complementary” and “integrative.” Non-M.D. practitioners in Maryland cannot prescribe conventional medicines or act as a primary-care provider, but say they work in concert with conventional doctors in the care of patients. (Since he’s an M.D., Hinderberger can, and sometimes does, also prescribe conventional medicines.)

For conventional doctors, the chief concern about alternative therapies is the risk of self-diagnosis and that a serious problem could be missed, says Mercy Medical Center orthopedic surgeon John-Paul Rue. Rue say he’s neither for nor against homeopathy and other alternative therapies, as long as patients are not relying on homeopathic remedies for acute injuries or significant illness, and they continue to be followed by a doctor who can be certain the treatments won’t interfere with conventional medicine.

“I think most homeopathic treatments are probably fairly innocuous,” he says. “The fear would really be what we’re missing.”

for Simon, who went to the emergency room and not a naturopath when his appendix burst, there’s room for both conventional medicine and homeopathy. “I always say if conventional medicine has something and there is proof that it works, take it,” he says. “But there are many times when conventional medicine doesn’t cure, and it’s not surprising that somebody who has a problem goes and looks somewhere else for what conventional medicine isn’t able to do.”

As for the criticisms of homeopathy, he’s unswayed. “You really have the scientific world having a hard time taking it seriously, and nobody wants to look at it and explain it,” he says. “But I tried it and it worked for me. Why wouldn’t I keep using it?”