A childhood illness forever shapes the life of a Sinai Hospital doctor.

Home & Living

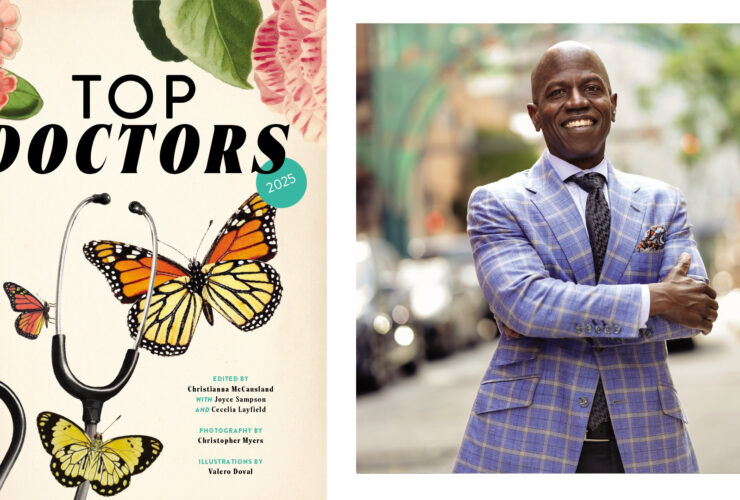

Miracle Worker

A childhood illness forever shapes the life of a Sinai Hospital doctor.

Dr. Jonathan Ringo keeps the kind of schedule that would leave men half his age utterly exhausted. After morning prayer at the Jewish seminary on the Pikesville campus on which he lives, Ringo, 49, makes the short commute to Sinai Hospital of Baltimore, where he serves as president and chief operating officer. At work, he deals with everything from construction issues to contract negotiations to overseeing a staff of 4,800 employees. As a practicing obstetrician-gynecologist, once a month or so, he delivers a baby. He takes time to pray in the middle of the day and, in the evening, often eats dinner with a board member or another physician to talk shop. He answers emails and takes phone calls while walking on his new treadmill desk at work (at the pace of two to three miles an hour), devotes as much time as he can to his brood of six, helps with their homework, swims a half mile three times a week, and manages to study the Talmud before going to bed past midnight.

Relying on a steady stream of caffeine and strict self-discipline, Ringo says that sleep is about the only thing he doesn’t fit into his schedule. By his count, he takes roughly 15,000 steps a day. “You don’t want to miss an opportunity,” is how he sums up his credo.

It wouldn’t take an attending psychiatrist at Sinai to read between the lines of Ringo’s life. Forty-three years ago, the good doctor almost died—and the fact that he didn’t provided the leitmotif to his life.

Sitting in his homey office on the first floor of the 152-year-old hospital—one of the first to treat and train Jewish people—Ringo, an Orthodox Jew, recounts how he came here by way of his native South Africa, first arriving in the U.S. in 1975 as a 6-year-old patient at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

“I had a typical childhood,” Ringo says in his South African accent. “But one day I was playing field hockey and my friend hit me in the nose with a hockey stick. Obviously, my nose was bleeding—and it had stopped bleeding—but that night it started bleeding again. My parents couldn’t get it to stop. It bled. And bled. And bled.”

After many hours, Ringo’s mother was able to control the bleeding, but the next day, she remained troubled by the experience, her mother’s intuition kicking in. “She just had this premonition,” Ringo recalls. A general practitioner agreed to run a blood test to placate the anxious mom. And then the worst happened. “We lived in the small town of Germiston outside of Johannesburg,” says Ringo, “and the doctor called my father and said, ‘Look, you need to come home for lunch.’ Then he sat down at our family’s table and said, ‘We made the diagnosis of leukemia.’ He later told my parents it was one of the worst days of his career.”

Stunned by the news, Ringo’s parents drove him to the children’s hospital in Johannesburg for further evaluation and a bone aspiration to determine the exact type of blood cancer. With lab results complete, the news went from bad to worse: It was a fairly rare type of blood cancer known as acute myelogenous leukemia, AML in medical shorthand, a cancer of the myeloid line of blood cells characterized by the rapid growth of abnormal cells that build up in the bone marrow and blood and interfere with normal blood cells. At the time, the cure rate was no better than 10 percent.

“My parents were told, ‘There’s nothing we can do—just take him home and keep him comfortable,’” Ringo recalls.

Undaunted, his mother looked at the doctor and said, ‘You’re the first person I’m going to invite to his bar mitzvah.’”

With lab results complete, the news went from bad to worse. . . . At the time, the cure rate was no better than 10 percent.

While many people thought that the Ringos were making a mistake by intervening, they contacted the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, where a friend’s brother was a physician. That physician encouraged them to make the nearly 8,000-mile journey. “There were some people who were critical of my parents for taking me away,” says Ringo. “They said, ‘He’s going to die in a strange country—you’re not going to have any support there. You’re just torturing him.’”

Despite the grim prognosis, the Ringos refused to sit by and watch their son die. “By the time we came to America, I was so much weaker,” says Ringo. “My father had to literally carry me just because of the disease progression within a week.”

A young medical fellow by the name of Howard Weinstein was at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute at the time, and Ringo became one of his patients. “I spent lots and lots of time with the family back then,” says Weinstein, who is now chief of pediatric hematology-oncology at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, “and I remember when his parents first came to Boston from Johannesburg, they were pretty panicked. Jonathan was amazingly easygoing. He was always an upbeat kind of a kid, a real trickster. His dad would go to the joke shop that was nearby, and he and his dad would play pranks on the doctors and nurses.”

Treatment began right away, with high doses of powerful chemotherapy cocktails, including different combinations of drugs such as Adriamycin, mercaptopurine, and cytosine arabinoside. “It was the perfect storm of treatment for Jonathan,” recalls Weinstein. “Prior to his arrival, we were not treating patients with AML so aggressively. At the point we treated him, there was still a very active debate in the world of childhood and adult cancer care about how aggressive to be for folks with AML—the thinking was not to treat it aggressively because it wouldn’t make a difference.”

At times, the side effects made Ringo as sick as the disease itself. He lost his hair—and his appetite. He developed mouth ulcers. He required so many infusions that doctors used the veins in his legs for procedures. “My mother was there by my side the whole time,” he says, “and she was like, ‘We’re going to get through the next five minutes, the next hour, the next day.’” Within three to four months, he was in remission.

Dr. Jonathan Ringo often works while walking on his treadmill to get the most out of every day.

Over the course of two-and-a-half years, Ringo and his family traveled between South Africa and Boston. “Because no one had made it as far as I had in the protocol, they weren’t sure when to stop treatment,” says Ringo. “Dr. Weinstein said that one of the hardest decisions he ever had to make was to discontinue treatment—no one knew what would happen. I had a blood test once a month at first, then every three months, and then every six months. The first couple of years, we came back for every bone-marrow aspiration.”

Weinstein became so bonded with the boy that he flew to South Africa on several occasions to work in concert with doctors on his follow-up care, and, yes, to attend Ringo’s bar mitzvah. (On the day of his bar mitzvah, there was, in fact, a headline in the Germiston paper that said, “Joy of a Teenage Boy Who Should Be Dead,” says Ringo, smiling at the memory, “and, ironically, the doctor from Johannesburg had died several years before my bar mitzvah.”)

Not only did Ringo survive, and eventually thrive, but his treatment had far-reaching implications. “We learned an awful lot from the therapy that he received and used it as a building block for future therapy,” says Weinstein. Ringo’s therapy led to the development of a clinical trial of a protocol that started the year after he finished, increasing the survival rate from 10 percent to 50 at the time, explains Weinstein. “It is still a difficult leukemia to treat, but we made headway—and now the survival rate is 50 to 70 percent.”

Even decades later, Ringo can cite chapter and verse the names of the drugs he was infused with, the names of the doctors who treated him, the months and years that he went into remission, and the practical jokes that he played with his family to add some levity to his life.

“I’d handcuff nurses to the IV pole,” he says, laughing. “And one of the side effects of the drugs was diabetes, so they’d dip a stick in my urine every morning. One day I took a packet of sugar from breakfast and dumped into my urine.”

To date, Ringo is one of the longest survivors of myelogenous leukemia in the world. The only real reminder of his illness is a barely noticeable scar above his left eye from a chemo-related bacterial infection that led to an abscess excision. “I also missed out on two years of childhood growth,” he says, “but I’m over six feet.”

As a kid Ringo once entertained thoughts of becoming a fireman or policeman, but his time as a patient made medicine his calling. “The physicians who took care of me were the most brilliant, caring, compassionate people,” he says. “They were great role models for how to take care of people. I can still remember Dr. Bruce Camitta, one of the first doctors I saw when I was examined at Dana-Farber. He sat down with me and drew good and bad cells. He explained to me what was going on—I still remember that 40 years later.”

Before pursuing medicine, Ringo worked in the biotech field for six years. By 1998, he found himself in Baltimore because he had a sister living here and was dating the daughter of a Baltimore rabbi. (He later married her.) By 2004, he was pursuing his dream and enrolled in medical school in St. Kitts and Nevis at the International University of Health Sciences. After medical school, he ended up back in Baltimore, eventually specializing in obstetrics and gynecology because of the broadness of the field. “You have pregnant women with diabetes and, all of a sudden, you’re dealing with two patients, not just one,” says Ringo.

“The physicians who took care of me were the most brilliant, caring, compassionate people. They were great role models.”

on a late July day, wearing a pinstriped suit, a velvet kippah, and a blue tie that matches his eyes, Ringo stops by the pediatric unit to accept a large donation from a family that lost their young son to cancer. Later, he makes the rounds with Director of Patient Experience Katie Starkey. Together, they visit various floors to check in on staff and patients. As he wanders through the infusion center, he stops to chat with a patient and introduces himself. “I’m meeting the big boss today,” she says, smiling. “Is there anything you need? How are you doing?” he asks. A few steps down the hallway, he stops in to see another patient. They speak about her relatives in South Africa, and he congratulates her on her clean PET scan.

“I have to remember, I didn’t choose banking or finance,” he says as he walks away. “I chose medicine. This job requires daily compassion.”

Ringo’s past is never far from his present. “My leukemia was a gift of life,” he says. “It was such a positive thing. It gives you a different appreciation of every day. In our hospital here, above the elevators, there’s a saying from the Talmud that says something to the effect of, ‘If you save one life, you save the whole world.’ I have that here with these photos of my six kids over my shoulder—that’s all a result of that.” And though his days are busy, taking time for thrice-daily prayer allows time for reflection.

“There’s a prayer that you say in the morning that talks about gratitude and the gift of the body and how if one particular vessel was closed or another open, you couldn’t exist,” he says. “It reminds you on a constant basis of the miracle of life.”