Health & Wellness

Fire in the Brain: Work Toward Multiple Sclerosis Breakthroughs Continues in Baltimore

MS affects at least a million people in the U.S.—including the writer’s mother and late mother-in-law. Progress on treatments has been made, but we’re still far from a cure.

Eleven years ago, Jamie Hoffberger, a 27-year-old Pikesville native who had recently returned home from living in Israel, walked into a renovated corner bar in Canton looking to rent a room in its three-bedroom apartment. The two current tenants gave her a tour. As she looked around the funky remodeled first floor, a particular feature outside the window caught her eye.

“Look, there’s a handicap ramp,” she said. “My mom will love that.”

“Your mom?” said one of her would-be roommates.

“Yeah, she has MS,” Hoffberger said, using the familiar abbreviation for the disease multiple sclerosis. “She uses a wheelchair.” The other typically reserved potential roomie stood, stunned.

“My mom has MS too,” he said.

That was me.

Judy Hoffberger, Jamie’s mom, wasn’t there that day. I would learn that she rarely traveled from home because the exhaustion and pain she experienced in her body were too much to bear, yet I would get to know her well. Jamie moved into that Canton apartment on the corner of Hudson Street and Luzerne Avenue, we fell in love, and in 2017 we got married. Today, we have two little kids. In the euphoric, early stages of our relationship, a first-hand understanding of MS—an often-debilitating chronic autoimmune illness—was a significant thing we had in common.

The disease attacks the brain, spine, and central nervous system, and can cause unpredictable effects, like numbness and tingling in limbs, mood changes, memory problems, fatigue, blindness, and even paralysis. It affects at least one million people in the U.S., three million globally, and women three times as much as men. Coincidentally, my mom and Jamie’s mother endured one of the more terrifying early MS symptoms; they each woke up one morning—my mother-in-law around 1980 and my mom in 1994—suddenly unable to see.

However, their experiences had one notable difference. Jamie’s mom already had progressive MS. The disease manifested in her when she was in her 20s, sadly before any of the effective treatments for early-stage MS were on the market. By the time we met, she couldn’t see well enough to drive, even if her body would have allowed it. She needed help to move all but her arms. Over the next few years, her muscles thinned and she spent more and more of her days in bed, though her mind remained sharp.

“I’d like to come back in another life as a limo driver,” she would say, explaining that she would get to be behind the wheel of a car and go different places all day long. That was just one of many humorous, humane quips that made her the most upbeat person I’ve known. When asked how she was feeling, she usually replied that she was doing “wonderful.”

Meanwhile, my mom was diagnosed roughly 15 years after Judy, and in her late 30s. She did not and still doesn’t need to use a handicapped ramp. She has what’s called relapsing or remitting MS, the early stage and treatable form of this wretched, frustrating disease. Her initial symptom of blindness eventually went away. She still experiences some MS symptoms, like numbness in one leg and vision issues, but mercifully has lived an active life for three decades, playing golf and tennis, for example, thanks to the MS drugs she takes.

“I’m grateful,” she told me recently from Long Island, where she lives with my dad. “When I was diagnosed, all I knew about MS was there wasn’t a cure.”

Thirty years later, there still isn’t, but more is known about the disease today than ever before. And the work on more breakthroughs continues, including here in Baltimore.

The famous French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot was the first to describe MS in 1868 as “sclérose en plaques.” In Charcot’s day, he observed symptoms in a young Parisian woman—reportedly a tremor that he’d never seen before and other neurological problems, like slurred speech and abnormal eye movement. When he examined her brain after she died, he found multiple tiny areas of sclerosis, which in Greek means hardening. Charcot found more of the same in other patients.

Today these millimeters-sized plaques, also known as lesions, can be found in living patients with an MRI, presenting as bright white spots or flares on otherwise standard dark gray images of the brain. And, roughly 100 years after Charcot’s discoveries, doctors in the 1960s linked the abnormalities—damaged brain tissue—to a misguided immune system.

In people with MS, certain white blood cells meant to keep a person healthy erroneously attack the protective coating—myelin—of the roughly 85 billion neurons in the brain, or the spine and central nervous system. The reason why, if there is a singular one, is not known, but the outcomes of the mistaken attacks are. The so-called demyelination that occurs inflames nerves and disrupts signals to and from the brain, which can cause an array of neurological symptoms.

“If your nerve wires—what we call axons—are like the trunk of a tree, the myelin is wrapping around it like the bark,” says Dr. Peter Calabresi, longtime director of the Johns Hopkins Multiple Sclerois Center. “And like a forest fire, a little spark in the right place with dry tinder and no rain can sometimes light up an area. For reasons we don’t understand, sometimes people have an attack and then it quiets down and they don’t have another one.”

“But for a lot of people,” he continues, “there’s a kindling phenomenon. One attack begets another and probably there’s just a little bit of inflammation that doesn’t get quieted down and spreads to an adjacent part of the brain. More immune cells go in there and add fuel to the fire, and there’s a lot of myelin for them to find. That’s what we think happens.”

“I absolutely believe that the number of patients with multiple sclerosis are probably being underestimated…this is an important question that our health care system’s going to need to reconcile.”

The complexities around MS can be confounding. Most people are diagnosed between the ages of 20 and 50 and may seem otherwise healthy. One person’s experience of the “fire in the brain” may be completely different from another’s. And because many common early MS symptoms are invisible to observers and mirror other illnesses, what might actually be MS can be rationalized by patients and overlooked by doctors. Even though today the disease can be confirmed relatively easily—by observing symptoms and counting the number of lesions on an MRI after an episode—MS can often be misdiagnosed, even for those with adequate access to quality health care.

Actress Selma Blair, for example, was not properly diagnosed for decades and now requires a cane to walk. Baltimore-born television personality Montel Williams was told his neurological symptoms were all in his head for 10 years. The actress Christina Applegate, diagnosed in 2021, has said she wished she paid attention to the early signs of the disease, like when she felt off-balance for no reason filming dance scenes for a movie. “But who was I to know?” Applegate said last year.

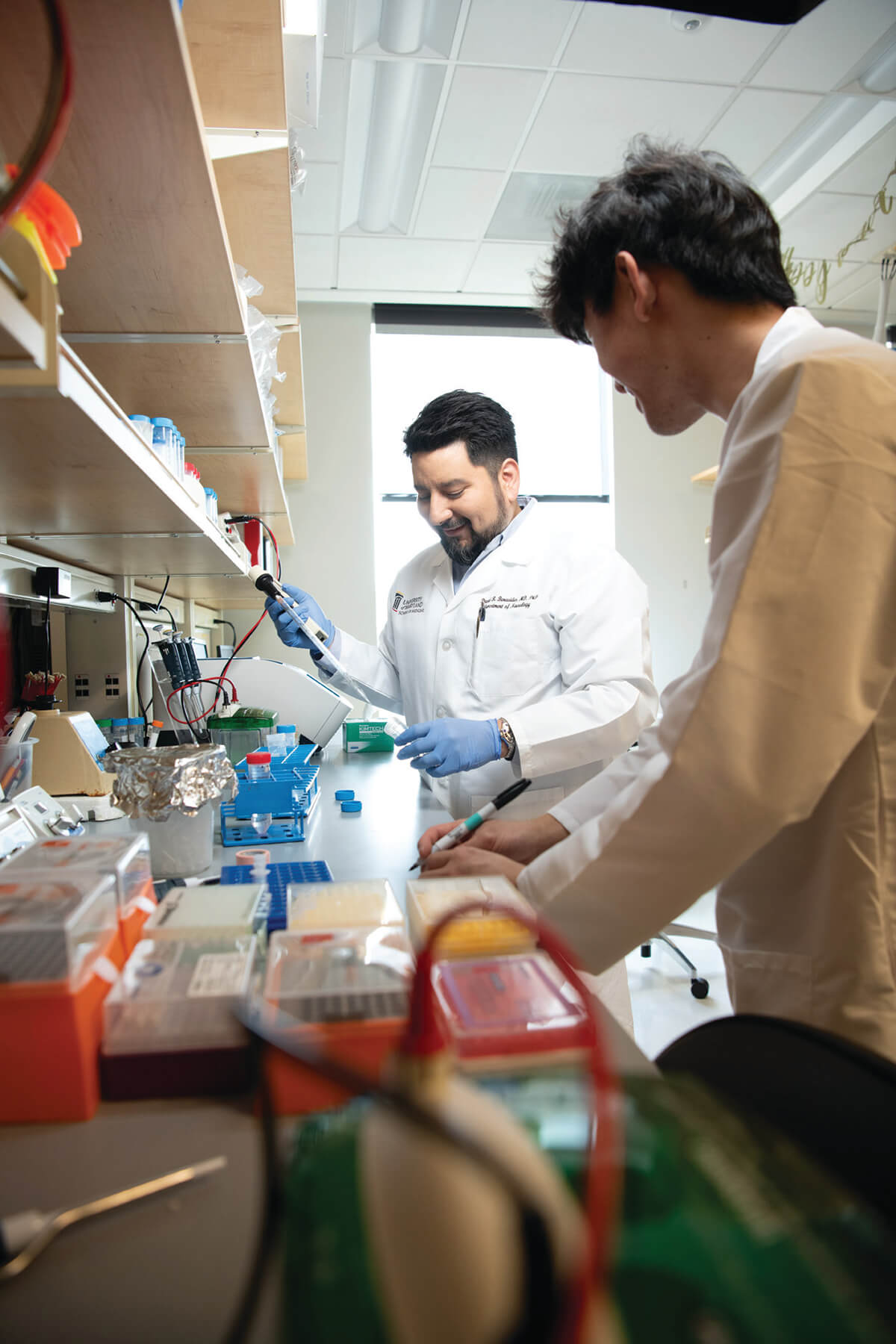

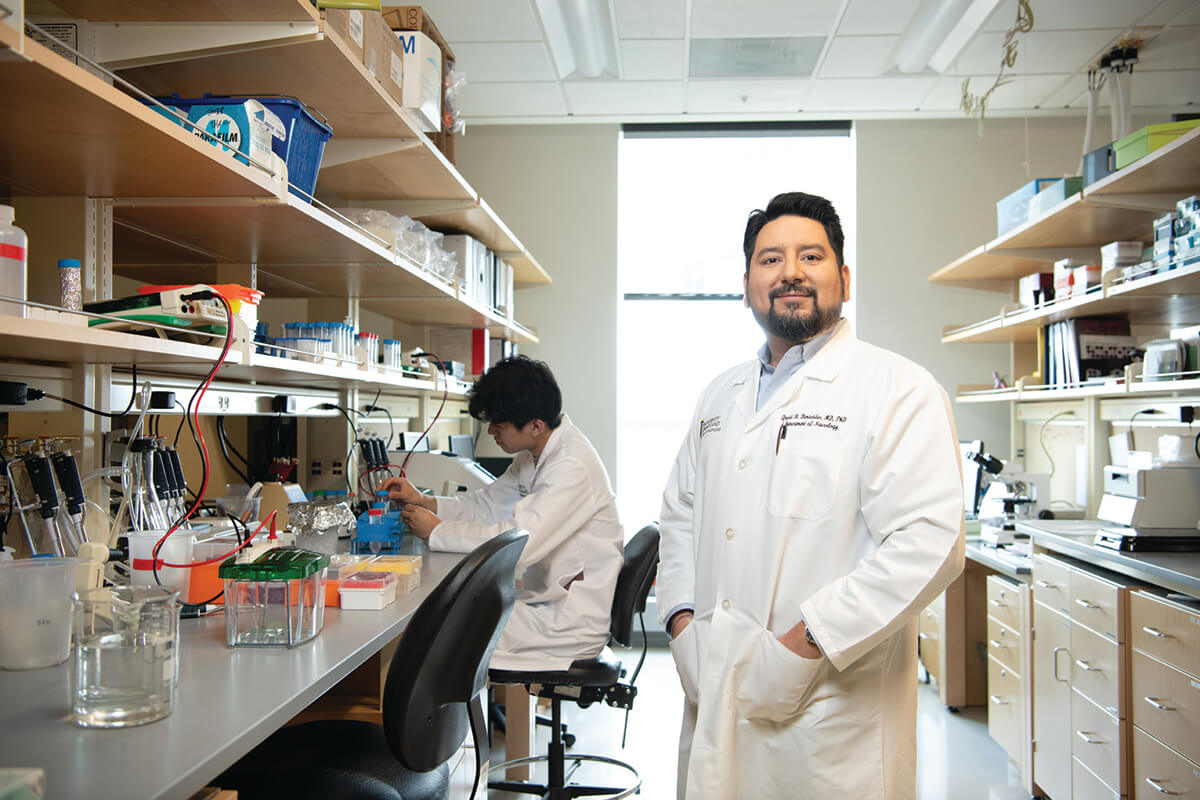

“I absolutely believe that the number of patients with multiple sclerosis are probably being underestimated,” says Dr. David R. Benavides, an assistant professor of neurology at the University of Maryland since 2017, who researches autoimmune and neuroinflamatory diseases like MS. Benavides says the lack of universal access to providers who are knowledgeable about the disease, coupled with the possibly prohibitive costs or lack of access to tests like MRIs in underserved populations, likely contribute to MS being underreported. “This is an important question that our health care system’s going to need to reconcile,” Benavides says.

The better news is MS is treatable if identified early enough. Hundreds of millions of dollars spent on research over many decades has led to roughly two dozen FDA-approved treatments designed to prevent more attacks from occurring in those with relapsing-remitting MS. The drugs—pills, injectables, and infusion therapies—are not guaranteed to work and are not without side effects (most commonly they leave the body more vulnerable to infections because of a weakened immune system), but studies have shown them to be effective in a large percentage of patients.

“In a relatively short amount of time, we’ve gone from zero to over 20 disease-modifying therapies,” says Bruce Bebo, executive vice president of research for the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS). “In the time when there were no disease-modifying therapies, a person could expect to have two or three or four relapses a year. Now, if you’re on an effective treatment, you should expect maybe one every five or 10 years.”

My mom is one of those enjoying the benefits of these drugs. She has five lesions, some in her brain and others on her spine. Thankfully, she hasn’t had what’s considered a relapse since waking up blind that morning when I was eight and my brother was 14.

“I remember thinking I would never be able to see my husband or my children again and my days of running and playing with them were over,” my mom says now, recalling the episode, which also numbed her right leg and weakened her left. A course of steroids, which reduces inflammation, resolved my mom’s vision and a neurologist prescribed her the first FDA-approved MS drug, Betaseron, an injectable, refrigerated drug that’s thought to reduce the body’s immune response and limit the number of cells that attack myelin.

For years, my mom self-administered a needle, or my dad did it, every other day, often leaving her legs bruised. One of my childhood memories is the sight of a dry-erase Betaseron-branded calendar stuck to our kitchen refrigerator, used to keep track of her shots. On vacations, my mom traveled with a cooler of medicine on ice. Her right leg remains numb to this day and probably will forever. She still unpredictably loses vision in one eye temporarily, but the weakness in her left leg went away soon after starting treatment.

A few years ago, she switched to taking a twice-daily oral capsule medication called Tecfidera, which is thought to modulate the immune system response to be less inflammatory and may have antioxidants that protect against damage to the brain and spine. All things considered, she’s been lucky.

My mother-in-law, Judy, trialed a version of Betaseron at the University of Maryland under MS research pioneer Dr. Ken Johnson when it was in development, but it worked with only brief effectiveness for her, given the disease had already turned progressive. As she aged, Judy went from being a working mom of two who enjoyed playing squash regularly to using a cane and then a wheelchair as her body deteriorated. Her illness was such that she couldn’t attend our wedding, though she saw and heard as much as possible. (A friend FaceTimed the ceremony and we immediately video-chatted after.) Judy passed away in the fall of 2020, at age 68.

“So many times, the people who end up with progressive MS are people who just didn’t get treatment early enough,” says Calabresi, returning to his metaphor about what happens to nerves in people with MS. “If you burn the bark off a tree and expose the trunk, and leave it bare to the elements, sometimes the trunk of the tree will burn and the tree falls over, and this is what I think happens after relapsing that predisposes to progressive MS.”

Calabresi, who has worked at Johns Hopkins since 2003, after a three-year stint at University of Maryland, wasn’t speaking specifically about my mother-in-law, but he could have. He was Judy’s doctor for many years. We began an interview a few months ago talking about our mutual admiration for her and his interest in medicine that dates to high school. Calabresi’s father, Paul, was a prominent oncologist who taught at Yale and Brown. His son gravitated toward diseases of the brain, and MS, which he found affected so many young adults in the prime of life. Today, “Dr. Calabresi is one of the leading MS experts in the world,” says Bebo of the NMSS, of which Calabresi is a scientific advisory board member.

Science, Calabresi tells me during a wide-ranging conversation, has brought MS treatment a long way, but not far enough for those with progressive MS, and not at all in terms of prevention.

“It would be really cool to just prevent MS from happening,” says Calabresi. “But it’s multifactorial. It’s probably very, very complicated.”

I was relieved when he reassured me that MS is not a single-gene disease that might be passed down through your parents. The chances of my children getting MS—despite having two grandmothers who suffered from the disease—are said to be the same as the general population. Yes, there are certain genes, more than 200, that may increase your risk of getting MS, and some of those are associated with people of Northern European ancestry, for example, but they are “not useful clinically. There’s not one thing you can test for,” Calabresi says.

What may be more useful for MS treatment and prevention, he says, is looking at genes linked to how the brain responds to injury. Calabresi’s name was one of many on a paper published on this topic in late June in the journal Nature.

“One thing that has struck me is that some people do very, very well, even on mild treatment. And some people end up in a wheelchair in less than 10 years, despite everything. There probably is something genetically different about the people who have very bad, aggressive MS,” he says.

Environmental considerations, like Vitamin D deficiency, smoking, obesity, and—most notably—increased exposure to viruses that can provoke the part of the immune system associated with MS, are also potential risk factors. In recent years, a new theory has emerged that previous infection with Epstein-Barr, a herpes virus that infects 95 percent of adults and can cause mononucleosis, may trigger MS.

It turns out the Epstein-Barr virus has a composition that looks a lot like pieces of myelin, which can confuse immune cells into attacking the protective nerve coating if Epstein-Barr is not completely cleared from the body. In a study conducted over the course of 20 years by Harvard that tracked 10 million young adults in the military, roughly 1,000 got MS. The study findings, published in January 2022, found a 32-fold increased risk of getting MS after having Epstein-Barr virus.

“It’s basically a case of mistaken identity,” Calabresi says. “The immune system is fighting off the virus, and then when the virus is gone, it goes around looking for anything that looks like the virus. And the immune system starts to chomp on that a little bit and kill it. We think that’s how MS and maybe a number of other autoimmune diseases are triggered.”

That’s just one theory, though. Calabresi says he would be surprised if Epstein-Barr infection were the only trigger for MS. He mentions a colleague in Switzerland who is investigating evidence that certain gut bacteria could also look like myelin, leading to a similar misguided immune response.

“Diseases are complicated and we always try to over- simplify them and pretend there’s one cause or one gene,” Calabresi says, “but it’s rarely that way.”

To that point, Benavides points out that previous infection with Epstein-Barr or other viruses can lead to other autoimmune disorders beyond MS, like some types of lymphoma.

In recent years, a new theory has emerged that previous infection with Epstein-Barr, a herpes virus that infects 95 percent of adults and can cause mononucleosis, may trigger MS.

What is clearer today is that early treatment of MS can be life-changing. Two summers ago, and two months after giving birth to her second child, Molly Doran woke up in the middle of a summer night in her Mt. Washington home to feed her son. She felt so dizzy it stopped her.

“I almost fell off the toilet,” she says. But her son, James, got his milk and she went back to bed, attributing the room spinning to sleep deprivation or something postpartum-related. “Then I woke up the next day and I was still dizzy,” Doran says.

When the dizziness persisted for a week, whenever she moved her head, it concerned her much more.

Doran, then 33, was a healthy, college-educated, married, working mom. She visited two more doctors. Vertigo remained her diagnosis. Among other things, exercises were recommended. They didn’t work. Then she started experiencing weird tastes when she ate familiar food. Then double vision. Then one night, one side of her face went numb. Doran’s mom, a physical therapist, had just gone through a stroke training course and suggested her daughter go to the emergency room. There she got a CAT scan and left with another vertigo diagnosis.

“I was fed up,” says Doran. She connected with a neurologist recommended by a family member, seeking a referral to another specialist who might fix her vertigo.

Before doing that, the neurologist asked to see her in person. He put Doran through a neurological physical exam, which she failed spectacularly, and he sent her immediately to the ER at Sinai Hospital, where she received an MRI and a spinal tap. She was in the hospital for three days. Doctors thought the likely suspects for what was wrong with her were Lyme disease or another infection. She was told her scans looked fine, but her neurologist said whoever read them missed something.

“I had a pretty sizable lesion on my brainstem,” Doran says, recalling the whole ordeal while sitting on the patio at a local Starbucks. Her doctor ordered more scans, which showed at least one more lesion. Doran was diagnosed with Clinically Isolated Syndrome, or C.I.S.—defined loosely as inflammation of the brain or spinal cord that leads to a neurological episode. A course of intravenous high-powered steroids took care of her dizziness, strange tastes, double vision, and numbness. She was severely fatigued and weak but able to keep on mothering and working. But the medicine didn’t erase her anxieties about what might come next. C.I.S. is a potential precursor to MS and Doran, as a woman in her 30s, fit the profile of a likely candidate.

Doran’s neurologist, Dr. Braeme Glaun, who’d proven so vital in her diagnosis of C.I.S., suggested Doran get a second opinion. She went to Johns Hopkins for more expertise, guidance, and access to more testing. When Doran went on a vacation, she had steroid pills to take if a symptom popped up. She started exercising more, a suggested preventative measure. And every six months Doran would have another MRI to look at her brain. Her second one showed an additional, asymptomatic lesion.

“At that point, they were like, ‘Now it’s MS,’ because it happened again, but it was a silent one,” she says, explaining that, unlike her previous episode, this time she never felt dizzy, or anything else out of the ordinary.

Doran’s MS diagnosis launched her into a world of uncertainty. How would her brain and body hold up in the future? Would it all get worse? Would she need to use a cane one day like Selma Blair?

“What’s the difference between me and her?” Doran says now, exercise bag at her feet. “I still don’t understand it all.”

Doran is now on a twice-a-year, IV infusion of a medicine called Ocrevus, a monoclonal antibody that targets a type of white blood cell that instigates an attack on myelin in the brain. The goal of the drug is to suppress the immune system.

“You stay on treatment and where you are now is the way you’re going to be the rest of your life,” Doran recalls doctors telling her. Still, she struggles for peace of mind—and for good reason. Much about MS remains a mystery even to the doctors who know it best.

Today, the NMSS is invested in roughly 200 active multi-year studies totaling $100 million dollars. The main areas of research focus on how to diagnose people quicker and more accurately and how to treat progressive MS in those who may be diagnosed too late.

On the first point, the Johns Hopkins MS Center has been part of a group of institutions working with the National Institutes of Health on MS-specific MRI technology that detects one of the disease’s unique characteristics—a plaque or lesion with a vein in the center of it—which can help doctors differentiate a white spot on an MRI scan caused by MS versus something else, like a blow to the head that may result in a similar-looking mark.

Calabresi is also part of a group of Johns Hopkins researchers working to develop a blood biomarker test that essentially measures the amount of nerve damage a person may have. The test measures neurofilaments in the blood, which at high levels is a sign of axons—or the trees in Calabresi’s forest fire metaphor—breaking up.

Ultimately, the great hope is finding a way to repair myelin—regrowing bark on the charred tree.

“One of the important goals and milestones for the field is to have novel therapeutics that can help restore function in multiple cell types within the nervous system,” Benavides says, “to either turn them on or reengage them to repair, or remyelinate.”

Calabresi thinks this ability may relate to a type of historically overlooked cell in the brain named glia, Greek for glue. “People really thought they were glue cells that were just scaffolding for neurons, but they are doing a whole lot more than that,” Calabresi says. “They’re normally there to support the brain, but in diseases like MS, they’re actually participating in the damage.”

In experiments in Calabresi’s laboratory in mice, he’s found that when toxic glia cells in inflamed areas of their brains are turned off, it’s been more likely to lead to myelin repair in nerves.

“We need to get drugs in the brain that target the glia cells,” Calabresi says. “My goal now is to try to find something to help repair the damage or slow the ongoing damage.”

Broadly speaking, he says, “The great unmet need now is to understand why people slowly get worse, and the neurodegenerative aspects of the disease, which still elude us. When you’re young, you can compensate because your muscles are strong, but it’s right around 50 when people start to become progressive. Women go through menopause, and they lose their estrogen, which is protective to the brain. We know this is a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease, and the same appears to be true in MS.”

A similar yet different switch in the immune system flips during and after pregnancy. If they have MS, women tend to go into remission during pregnancy as the immune system is suppressed, then they may experience an uptick in symptoms afterward as the body resets. So, it turns out, Doran’s instinct that her dizziness was postpartum-related was right. It just wasn’t anything she could have imagined.

There was a fire in the brain to blame, a lesion, a sclérose en plaque.

Given the greater understanding of MS today and the effective treatments available, it’s likely Doran, and many others with early diagnosed MS, won’t have any more attacks. With any luck, she may end up like my mom and have trouble remembering how many lesions she has because MS, while always with her, doesn’t control her.

“Seven?” my mom replied when I asked. “No, no, it’s five.”

The next great hope is that people like my beloved, late mother-in-law—who lived with an infinitely positive spirit, but whose body betrayed her in an unstoppable way—could one day be cured.