Health & Wellness

By Jane Marion

Photography by Justin Tsucalas

ON A CRISP FALL DAY in October, Juan García rolls a black utility trunk down the well-lit corridors of the Johns Hopkins Outpatient Center past the Department of Gynecology & Obstetrics. But García, who is neither an ob-gyn nor even a doctor, is making a different sort of delivery. Inside the case, along with tinted silicone pigments, paintbrushes, a palette, wax molds, and photo references, there’s a silicone ear nestled in a bed of gauze. It’s the culmination of a multistage process that began several months back.

Today, known as “delivery day,” the ear will go to its rightful recipient.

MaryAnne, a 68-year-old woman from Northern Virginia, lost her right ear in an accident. In the aftermath, there was hope that the amputated ear could be reattached, but it proved too challenging.

“They were going to try plastic surgery but there were no blood vessels,” says MaryAnne (who prefers not to use her last name). “At my age, it was just too iffy, and there were a lot of surgeries. They weren’t even sure reconstruction would work.”

Some nine months after her accident, where there once was an outer ear, there’s now just an opening to the ear canal. As MaryAnne sits in a treatment chair, García carefully removes the lifelike ear from a beige case usually used to hold dentures. He holds it to her head to check the positioning, the color, and the blending of the edges so that it will sit seamlessly, just behind her ear canal, like placing the final missing piece of a puzzle. As García holds the right ear to the side of her head, it looks like a near replica of her left one.

García is a certified clinical anaplastologist and director of the Facial, Eye & Body Prosthetics Clinic, which is part of the Department of Art as Applied to Medicine at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Anaplastology is the technical term for a little-known field that combines art and science to yield high-quality prosthetics. Though Hopkins happens to have two clinical anaplastologists on staff, including García’s colleague, Andrew Etheridge, there are only 40-plus board-certified anaplastologists in the world.

With this intersection of art and anatomy, these medical sculptors are like modern-day Michelangelos, creating facial and body prosthetics so lifelike, it’s hard to discern the difference between what’s man-made and what existed at birth.

Together, García and Etheridge make a total of some 70 prosthetics a year. (They decline to discuss cost but emphasize that whenever possible, the prosthetics are covered by insurance under “durable medical equipment” in the same way that, say, crutches or an orthopedic boot get billed.) Patients come from the Mid-Atlantic, as well as all over the country and the world, including Dubai, India, Egypt, Chile, and other far-flung destinations. And they run the gamut from cancer survivors who’ve been left permanently scarred by the disease to people with congenital differences who were born without body parts to those who’ve suffered traumatic injuries or burns. The prosthetics literally run from the head—noses, eyes, ears, partial faces—to the toes.

For MaryAnne, the artificial ear represents much more than a cosmetic choice, helping her to heal in a less visible way. “I wasn’t really sure I wanted to do this,” says MaryAnne, her blue eyes welling up with tears. “[After the accident] I was just grateful I had my hearing and that it had healed. It could have been a lot worse and I am able to live a happy, full life. But I thought, ‘Well it’s an option—I should just do it.’ When I put on [the earlier wax version] last time, I really did feel complete again.”

Juan García holds a mask

of his own face that students created

to learn the art of making prosthetics.

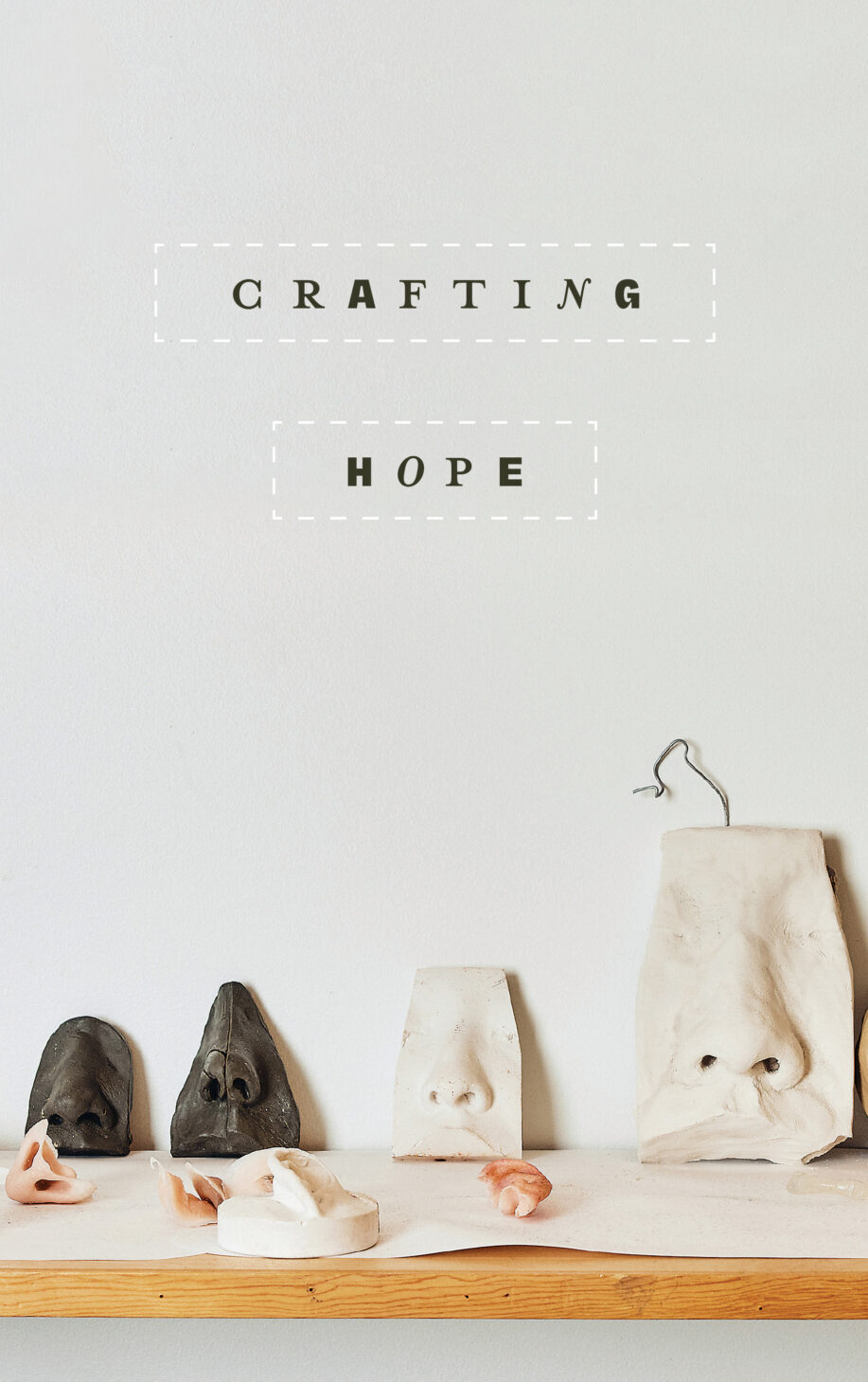

OPENING IMAGE: A shelf scattered with

various prosthetics in the lab at the

Department of Art as Applied to Medicine.

ANAPLASTOLOGY IS for patients for whom surgical reconstruction alone cannot restore facial features or appendages. In the case of an ear, for example, depending on the patient and the nature of the accident, a surgeon can sometimes use part of the unaffected ear or harvest the cartilage from a rib to create a new outer ear. But it’s hard to achieve the same result as what can be accomplished with a silicone replica. “Surgically, it’s very difficult to create these tiny folds of skin that project out and to get the blood vessels to support it,” says García. “And the definition of the shape is not as good sometimes—it takes a highly skilled surgeon to achieve that.”

When MaryAnne saw the less detailed wax mold at her last appointment, “I was like, ‘This looks great,’” she says. But today she will receive the fully sculpted, more refined silicone iteration with all its deep valleys, flesh-like folds, complicated crevices, textured surfaces, and everything protruding in the proper place. It’s the one she will take home, the one that will go on—and off—with medical adhesive glue, the one that will blend so seamlessly that no one will notice it’s not the real thing.

“Maybe I will wear my hair up more now and I can wear two earrings,” says MaryAnne, who came in wearing just one. (Yes, the anaplastologist can add an earring hole to the prosthetic.) “I’m just grateful that I’m healthy and can do anything I want to do. This is gravy—it’s the pièce de résistance.”

The next step in bringing the ear to life is to finish painting the prosthetic—already close to the color of her skin—in place. The soft-spoken García holds it against MaryAnne’s affected side, then moves back and forth between it and her unaffected ear to get the final tone just right.

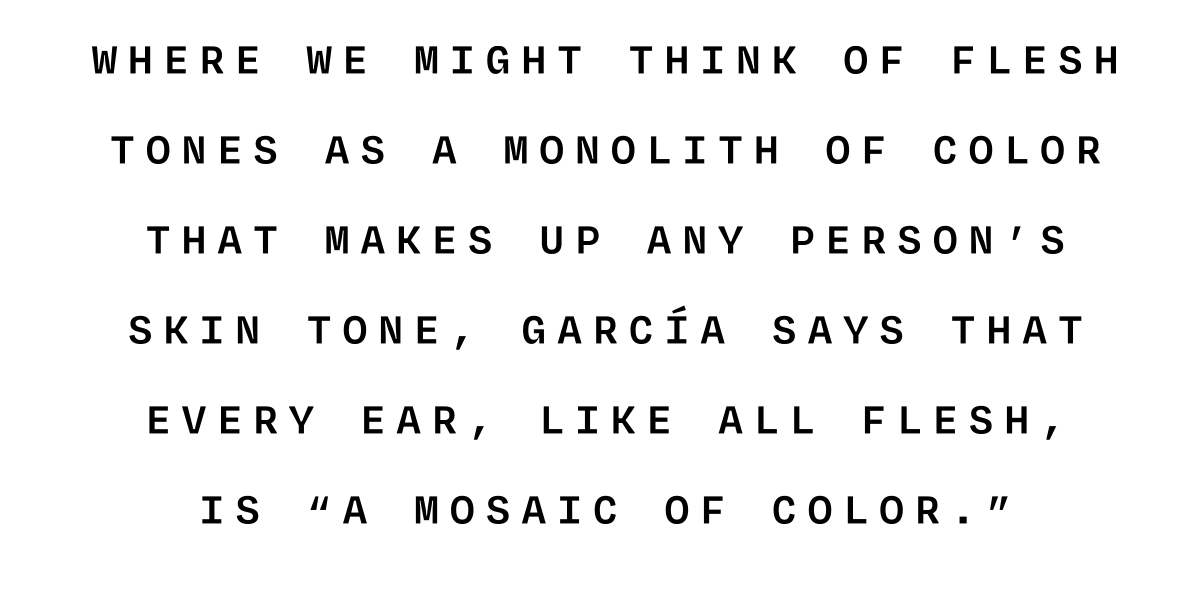

“Initially, I am looking at value [lightness or darkness] because that’s the most important thing,” he says. “And then I’m looking at the red tones.” Where we might think of flesh tones as a monolith of color that makes up any person’s skin tone, García says that every ear, like all flesh, is “a mosaic of color.”

“I am trying to match the overall color knowing that light gets reflected on silicone in a different way than it does on the skin,” he continues. “Where the light reflects through silicone, we put in little fibers of rayon into the silicone mix to mimic collagen and blood vessels.” To bring it all to life, other elements are included, too. “In her case, she has a very pronounced blood vessel,” García explains. So he incorporates a small piece of threading to mimic that vessel. “Those are the little details that make it convincing,” he says.

Over the next few hours, García dabs paint from his palette as he and Cherise Masuda, a graduate student whom he is mentoring, makes her own iteration of the appendage.

While the clinician and his student move between sides, MaryAnne sits patiently, a gamut of emotions flooding across her face. There’s excitement over finally getting the finished product, fear over the possibility that it could fall off when she wears it, anxiety about caring for and cleaning it, and relief that, at least for now, this chapter is coming to a close, though the prosthetic itself will likely need to be replaced every one to three years. When that time does come, García will head downstairs to the repository where the molds are stored for seven years so that he can easily duplicate it again.

“With the prosthetic, we are transitioning the person into feeling whole again and hopefully a lot more confident,” says García. “But there are limitations—it’s not their flesh.”

Juan García mentors

anaplastology graduate student Cherise

Masuda; applying silicone paint to a

prosthetic ear.

PROSTHETICS HAVE been around for thousands of years and early attempts, though rudimentary, were innovative for their time. An Egyptian toe (known as the “Greville Chester Toe”) is thought to be between 2,600 and 3,400 years old, and was made of cartonnage—a kind of papier mâché mix of glue, linen, and plaster. Because the toe doesn’t bend, researchers believe it was likely cosmetic, not functional.

The oldest known practical prosthetic is a flexible leather and wooden big toe (known as the “Cairo Toe”). Estimated to be between 2,700 and 3,000 years old, it belonged to a woman thought to be the daughter of a high-status Egyptian priest. Remarkably, the toe was refitted multiple times.

Some 300 years later, the ancient Roman “Capua Leg,” used by a nobleman, was made of bronze and hollowed-out wood and held up with leather straps. However, its weight and lack of flexibility likely made it impractical to wear.

Later, between the 5th and 8th centuries, there were artificial feet made from wood, iron, and bronze found in Switzerland and Germany and believed to have been strapped to the amputee’s remaining limb. In the 16th century, French surgeon Ambroise Paré designed some of the first purely functional prosthetics for injured soldiers and published the earliest written reference to the devices. Thanks to advances in metallurgy, from the late 15th century to the 19th century, France and Switzerland led the way in improvement in design, making artificial limbs that could rotate and bend using cables, gears, cranks, and springs for improved function. During the 1900s, plastics and other artificial materials replaced wood and leather.

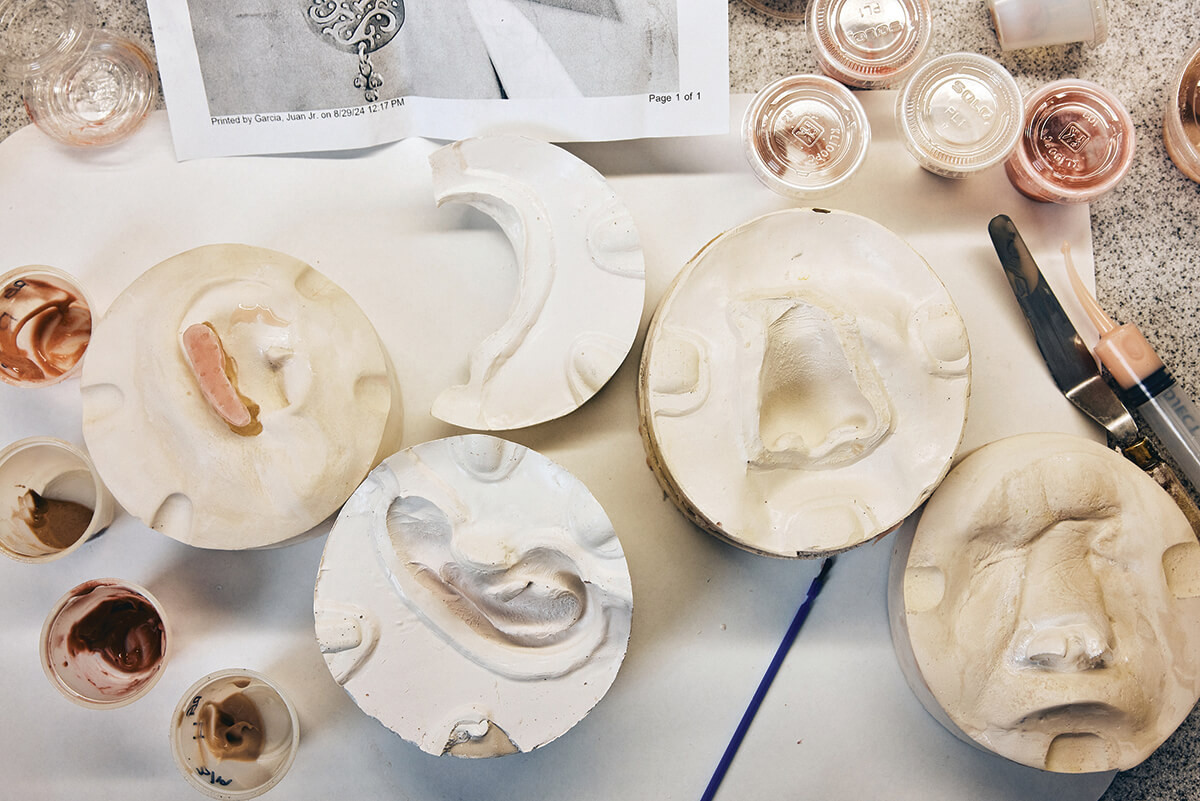

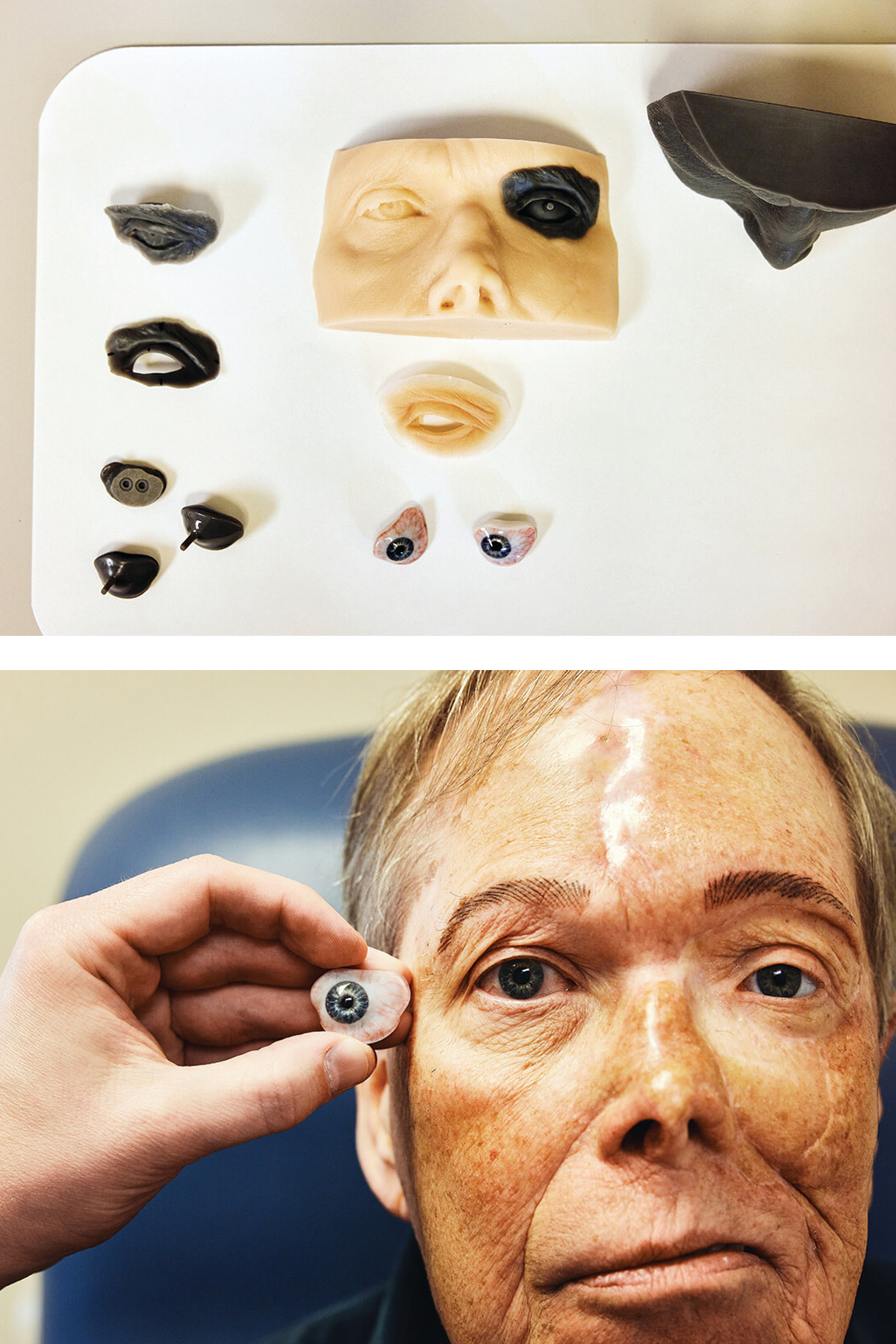

Ear and nose molds and a variety of silicone paints.

The battlefield inspired other advances, too. For example, the U.S. Civil War—a conflict that led to many amputations—prompted innovations like the “Hanger Limb,” featuring rubber in the ankle and cushioning in the heel for added comfort. By World War I, Boston sculptor Anna Coleman Ladd founded the Studio for Portrait Masks in Paris, creating galvanized copper face masks for soldiers disfigured in combat. And with the onset of World War II, exporting glass from Germany for prosthetic eyes was banned, necessitating the development of acrylic plastic eyes, and further pushing the field into modernity.

Whatever the means or methodology, the goal then was likely the same as it is today: to help heal not only physical wounds but emotional ones. The latter, notes García, can be as impactful as the former.

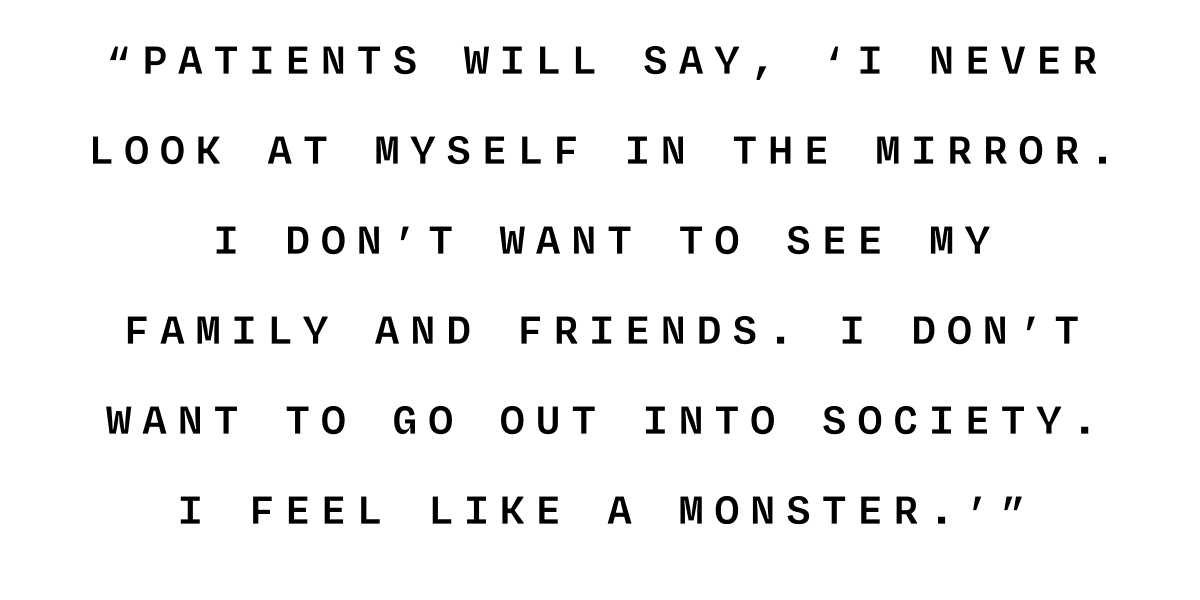

“Patients will say, ‘I never look at myself in the mirror,’” he says. “‘I don’t want to see my family and friends. I don’t want to go out into society. I feel like a monster’—that’s the reality for these patients. They are still missing their body part—we are not curing them of that—but we are rehabilitating them back into society to be able to interact with their loved ones and friends, to be able to go out socially without attracting the stares and the negative attention. Hopefully, they are camouflaged to blend in.”

Even after receiving a prosthetic, adjusting to life with one can take time. “What’s interesting is that in many cases, patients are cured of their medical condition,” says García. “However, now they have this other issue that they need to manage. It’s not just the scars, it’s also the psychological trauma.”

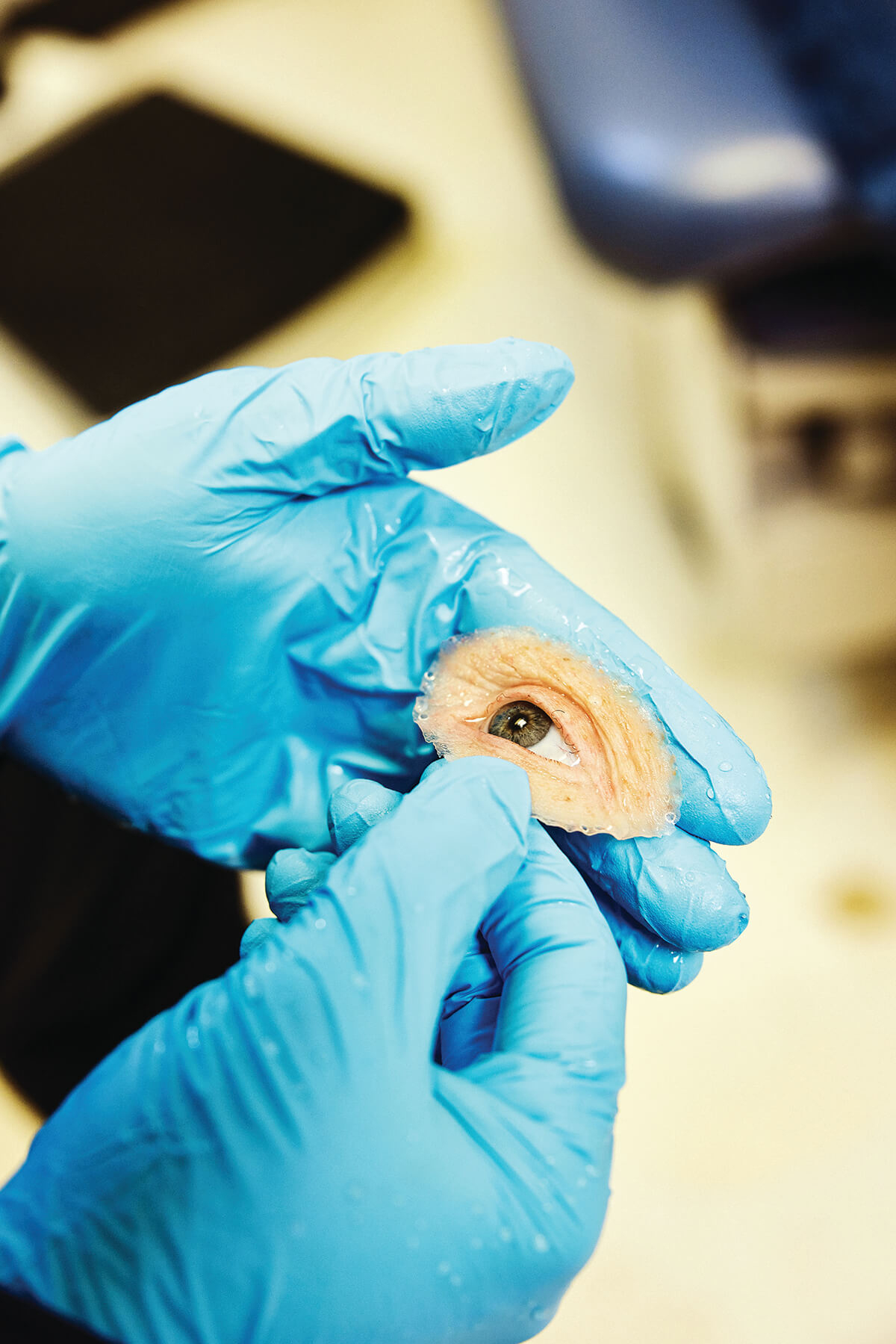

Andrew Etheridge

holds the acrylic eye of

patient Tom Warren.

The eye will fasten to the

socket with tiny magnets.

IN THE SPRING of 2021, Candie Fulks was laboring to breathe through her nose—she assumed it was just a bad cold. By the time she saw a doctor, she learned she had squamous cell carcinoma. The cancer, along the lining of her nose, would necessitate the removal of her nose, including excising ravaged tissue from her nasal cavity. Essentially, the surgery would leave a gaping hole in the middle of her face.

“If I had to cut my nose off my face, I was going to do it—I wanted to live,” says the now-51-year-old customer service specialist from St. Mary’s County. “It was a radical decision between life and death. Of course it was all a shock, and it was absolutely devastating, but you do what you have to do.”

Prior to surgery, Fulks consulted several plastic surgeons. “They couldn’t guarantee that I was going to look the same and I’d have to go in every two to three weeks and go under anesthesia [during the reconstruction],” says Fulks. “I was not willing to go that route.” After her doctor referred her to García, getting a prosthetic seemed like the right choice. “The prosthetic was more convenient,” she says. “And I could put it on and take it off whenever I wanted.”

After Fulks had surgery that fall, followed by rounds of radiation—and was finally cancer-free—she went to García, who took an impression of her nasal cavity to make a model of the affected area and used a 3D printer (using her CT data and photo references) to make a model of her nose. At Fulks’ request, he also altered the shape of her natural nose slightly. “He gave me a nose job,” says Fulks with a laugh. “I had a pug nose, and he thinned the prosthetic out a little bit.”

Now, since getting that first nose (followed by a duplicate version two years later), Fulks meets with García at the outpatient center on a sunny December day. She’s a clinic regular. Due to discoloration, normal wear and tear, and exposure to the elements, the nose is replaced regularly. This nose, her third one, will be closer to the one she lost.

“I told Juan I wanted something more of my original nose to match my smile lines,” says Fulks. “It was less realistic the first two times because I told him I wanted it to be less puggy. But after a few years, when I looked at myself in the mirror, I thought we should go back to my original nose.”

As Fulks tries on her glasses (which help hold the nose in place along with medical adhesive) and García checks for fit, an easy camaraderie between them ensues. García shares that he once thought he’d become a plastic surgeon. “You’re a wax surgeon now,” says Fulks, laughing.

Next, García works on the back side of the nose to make an impression for the all-important area where the nose will fit into the nasal cavity. Fulks tilts her head back as he dispenses a silicone material (the same substance used to take dental impressions) into the cavity, across her cheeks, and down to her lip line—it’s the prosthetic equivalent of a facial. “I can go a little deeper and engage more of the anatomy to help with retention,” he says as he works on making the extension that will help hold the nose in place when she wears it. “The first effort didn’t use the 3D technology to design the back of the nose—I’m now using 3D technology for the back as well.”

Several weeks later, Fulks has returned for delivery day—and she’s all smiles as she receives the final device, which looks more like her own flesh and blood than something fashioned from silicone and pigment. García places the prosthetic on her face, then adjusts the skin tone with paint to make it even more convincing. “This is where the real artistry comes in,” he says. But he acknowledges, “It’s never going to be perfect.”

Still, an hour or so later, as Fulks studies her reflection in the mirror, to the casual observer, it does look pretty close to perfect. “It looks so good,” she says. “Wow.”

Because this nose comes so close to the one she lost, as she gazes at her own reflection, Fulks now sees a familiar face staring back. “This just looks more like me,” she says. “I’ve always felt more complete with the nose than without it but this one takes the cake.”

Juan García

adds the finishing touches to Candie

Fulks’ nose; García adjusts the flesh

tones to bring the prosthetic to life;

Fulks wears her new prosthetic nose on

delivery day; the prosthetic nose was

months in the making.

JUST A FEW blocks from the outpatient clinic, the lab where the devices are made, sits inside the Department of Art as Applied to Medicine on East Monument Street. It’s not only where García and Etheridge work, but where anaplastology master’s degree students hone their craft. Exquisite carbon dust and pen and ink illustrations drawn by famed medical illustrator Max Brödel, who created the department in 1911, hang nearby in the halls.

Shelves are scattered with realistic-looking body parts: noses of every conceivable shape and kind, acrylic eyeballs, fingers, and face masks. Much of it is student work, and most of it based on actual cases. Raw materials are everywhere—there’s silicone, resin, wax, acrylic, clay, a rainbow of silicone paints, paintbrushes, plaster, sculpting and sanding tools, sealants, surgical gloves, 3D scanners and printers. The effect is science lab meets art studio meets Hollywood prop closet.

On this October day, grad student Jessica Liddicoat pours a model for a nose. Just down the hall, Cherise Masuda tinkers on a research project she’s doing with García’s colleague Andrew Etheridge to fabricate an index finger in which a conductive material embedded in the prosthetic will enable touchscreen sensitivity. When the duo graduate this May, they will join the rarified ranks of anaplastologists.

Anaplastology wasn’t a well-established field when García was growing up in Miami, where his father managed a store selling religious statues in Little Havana. At a tender age, he would travel to people’s homes and repair their relics—the finger of St. Barbara here, the tail of St. Lazarus’ dogs there, using a combination of wood paste, Krazy Glue, and oil paint. “I saw these statues,” he says, “and they were beautiful pieces of art.” It awakened in him an appreciation of art.

At University of Miami, he started out pre-med but soon followed in his older sister’s footsteps and switched his major to graphic design and illustration. Little did he know he would soon be combining his two passions.

In 1993, he attended grad school at Hopkins’ Department of Art as Applied to Medicine for medical and biological illustration. This appealed to both his love of art and his fascination with medicine. While still a student in the spring of 1995, he helped another student make an eye for a patient and soon decided to pursue the path of prosthetic making. Before long, he was traveling the world and studying under masters. To date, he’s a leading authority in his field.

In 2009, García established a supervised training certificate program in clinical anaplastology at Hopkins. And nearly three years ago, he helped establish a 22-month Master of Science degree in the field—the first graduate program of its kind in the world.

While every patient is different and no two prosthetics are alike, the basic process of making one follows roughly the same steps. First, the clinician captures the anatomy through making an impression or taking a 3D digital scan to help make a model of the affected area. Next, the clinician meets with the patient for a diagnostic wax prototype fitting and checks for what’s called “anatomical harmony,” possibly adding features to make it more lifelike. Later in the lab, fine details are added to the wax prototype—from freckles to human hair, and sometimes even tattoos.

From there, a custom mold is made—with silicone painted into the cavity of the mold to make the final device. For the final appointment, the device is brought to life with the application of more paint to adjust the base color.

“I like to tell patients, ‘It’s like baking a cake,’” says Liddicoat of the process. “‘The baking pan is what I have to make for you and then what goes in the batter is the silicone and we will match that base to the color of the skin, cast it, and then we do all the frosting, which is all the freckles and the color that makes it fully match’—that helps make it clearer to them.”

Devices that were once the stuff of science fiction are now becoming a reality. Etheridge, for example, is currently experimenting with making acrylic eyes on the 3D printer. (Overall, 3D printing has enabled more customized designs that are faster and more affordable to produce.)

Another recent project includes an “osteo-integrated” thumb, in which small titanium screws are implanted into the bone to hold the prosthetic in place—it’s the first device of its kind in the United States. “There are a lot of people who have proximal amputations that leave them unable to regain function or even don a prosthetic,” says Etheridge. “This will revolutionize how people can function with this type of amputation.”

Andrew Etheridge at work in the lab;

building Tom Warren’s ocular prosthetic;

Etheridge works with Warren on the fit

and finish of his prosthetic; Juan García

adds finishing touches on Fulks' nose;

an array of prosthetics in the lab.

Etheridge also recently worked on a complex facial prosthetic for a patient who lost the left part of the left side of his face after being diagnosed with a rare and aggressive cancer that forms in the lining of the blood vessels. To fabricate that prosthetic, Etheridge, who holds a master’s degree in sculpture and once contemplated a career in special effects, had to create not only an artificial eye but design the socket, known as an orbital implant, that holds it. That patient, Tom Warren, 68, of Columbia, calls his prosthetic piece, held in place by tiny magnets, nothing short of “magic.”

“This has given me a new sense of being a part of the community and not being disfigured,” says Warren. “Andrew has changed that for me—I’m not the freak anymore.”

Since those very early days of employing wood, leather, iron, copper, and other metals, materials have come a long way, too. Silicone, used for prosthetics since the ’70s, has not only added durability and comfort, but mimics the look and feel of skin with its translucent quality and flesh-like flexibility that allows it to move naturally with the body.

Twenty-one-year-old Amari Jones is one such beneficiary of those advances. Jones was born with Amniotic Band synprodrome, a condition in which fiber-like bands tangle around the fetus, restricting blood flow and causing abnormalities of the limbs (as well as other body parts). Sitting in the living room of her family’s Owings Mills townhome, the Towson University student talks publicly about her condition for the first time. “My story begins when I was born,” she says as she looks at her mother, Keshia.

On that July day in 2003, her parents were taken by surprise when their otherwise-healthy daughter came into the world with no toes on one side and only the ball of a heel on the other. Her fingers were webbed and required surgery to separate them when she turned one. “I had an ultrasound,” says Keshia. “But no one, not even the doctor, knew. When your child is born, you just want them to be okay. You hear, ‘As long as they have 10 fingers and 10 toes’. . . . Well, I couldn’t say that.” Still, says Keshia, “I always knew she’d be okay from the moment she came out.”

Sure enough, by age three, the spirited toddler was walking on the nubs of her heels, competing in cheer and gymnastics, and placing fourth in the state for the National American Miss Pageant, which fosters positive self-image. Amari, who exudes a quiet confidence, accepted her differences from the start. Still, she admits, “As I got older, sometimes I’d have moments where I was like, ‘I wish I had normal hands’ or ‘I wish I had normal feet,’” she says, “but I had to realize that everyone is created differently for a reason.”

As a young girl, Amari used a series of bulky braces for support. The braces, which were hard, heavy, and offered limited mobility, were covered by even bulkier socks. Amari often suffered from sores and calluses on her skin. As time went on, her devices got more natural-looking, but they were far from perfect.

“She had [prosthetic] feet that were like the hollowed-out feet of a mannequin,” recalls her father, Andre. “It was years of her just enduring the plastic. We kept asking about more lifelike prosthetics. Was this possible?” When the family met Johns Hopkins pediatric orthopedist Paul Sponseller, Andre recalls him saying, “‘This is a beautiful child—as she grows up, she might want to do different things.’ He wanted the braces to be not only more lifelike but more functional.”

Finally, last year, after being referred to Etheridge, Amari was able to obtain the prosthetics she’d long been hoping for. To design the feet, Etheridge scanned Keshia’s size-8 foot and, after reducing it to Amari’s size 5-6, designed the first prototype, a pair of silicone feet. After several hours of whirring, clicking, buzzing, and humming from the 3D printer, Amari and her parents watched the feet emerge from the machine.

Etheridge works on a prototype of Amari’s feet.

“I slipped them on,” recalls Amari. “Andrew had this aloe gel that I put on my feet and I just slid right into them. I walked with them on for the first time—and I had them on when I walked out of the hospital. I was like, ‘Wow, I could really get used to these.’ It was so easy to walk in them.”

Since that day, Amari has been thrilled with her newfound feet and the sores and numbing sensations are gone. “They’re really comfortable,” she says. “I really appreciate that the most about them.”

Sometime in February, she will receive her final feet, with more lifelike contours and colored to match her cocoa complexion. But the devices are not just cosmetic. “We are really adding lots of function, too,” notes Etheridge. “They won’t just look like her feet and have toenails she can paint, but will help her function in life—walking, driving, daily activities, and everything she wants to do.”

Another bonus? “She can wear heels now,” says Keshia, laughing. “Now she’s going to be in my closet.” Adds Amari, with a glint in her brown eyes, “I’m looking forward to wearing open-toed shoes and sandals, too.”

Andrew

Etheridge designing Amari Jones’ state-of-the-art feet; Amari Jones wearing her temporary

prosthetics at home; the silicone prototypes

made on a 3D printer.

BACK IN THE exam room with MaryAnne, García adds the finishing touches to her ear, making sure his patient is pleased. “Be frank with me if you need me to warm up or cool down the colors,” he says of the final ear. “You won’t hurt my feelings.”

“That looks good,” she says, gazing at her reflection. “You can’t even tell.” After painting on the final coat of silicone sealant, García asks if she’s brought the mate to her earring.

“It’s in my purse,” she says as Cherise Masuda removes it from the hook on the back of the door and hands it to her.

For months now, people who didn’t notice that MaryAnne was missing an ear have pointed out that she’s lost an earring. “And I’ll say, ‘Oh, thanks for telling me,’” she says, smiling. “They’re only trying to help.”

Today, MaryAnne reaches into her bag and hands García a delicate, silver disc which he slips into the prosthetic ear. “I am going to shed a few tears,” she says, welling up. “I can feel them coming—they are happy tears.”

Now, holding a hand mirror from the side and looking head on at the full-length mirror behind the door, for the first time in many months, she sees two earrings—and two ears. “It looks great,” she says, tearing up again.

“It will take two weeks to develop the muscle memory to put the prosthetic on,” García says.

“Should I worry about it falling off?” she asks nervously.

“It shouldn’t,” he says, “but wear it around the house for the first two weeks. It’s a new friend you are going to get to know.”

“And keep it away from kids and pets,” jokes García, breaking the heaviness that hangs in the room. “It’s an expensive chew toy.”

García asks MaryAnne to pose for a final photo for her medical file. Masuda snaps a photo of MaryAnne for her student portfolio.

“You’re my first ear patient,” Masuda says with pride.

MaryAnne’s husband enters the room and the ear is met with more approval, more awe, and more disbelief that this is not the real thing. A very real round of hugs follows, then she and her husband disappear down the hallway—and back to the ordinary, extraordinary business of life.