Health & Wellness

Despite His Chronic Illness, Mark Andrews is One of the Best Tight Ends in the Game

The Ravens tight end, who has Type 1 diabetes, doesn't let the disease define him. At 26 years old, he’s just entering his prime.

Beads of sweat still dripping from his coarse black beard, Mark Andrews emerges from the Ravens training facility munching on a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. After a mid-June practice under the stifling sun, one of the best tight ends in the NFL needs to get some food into his system. Not just because he’s hungry

“I just got an IV,” he says. “Didn’t eat like I should have last night. I had a huge lunch and didn’t eat too much for dinner. Glycogen storage was little bit depleted. I felt some cramping, so I wanted to get some fluids in me. And a little bit of complex carbs.”

Professional football players have a lot to worry about. Learning the playbook. Contracts. Injuries. Their Madden rating. But only a tiny percentage must constantly monitor their glucose levels while also punishing and pushing their bodies on the field. There are seven active NFL players with Type 1 diabetes according to the nonprofit JDRF (previously the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation).

Mark Andrews is one of them.

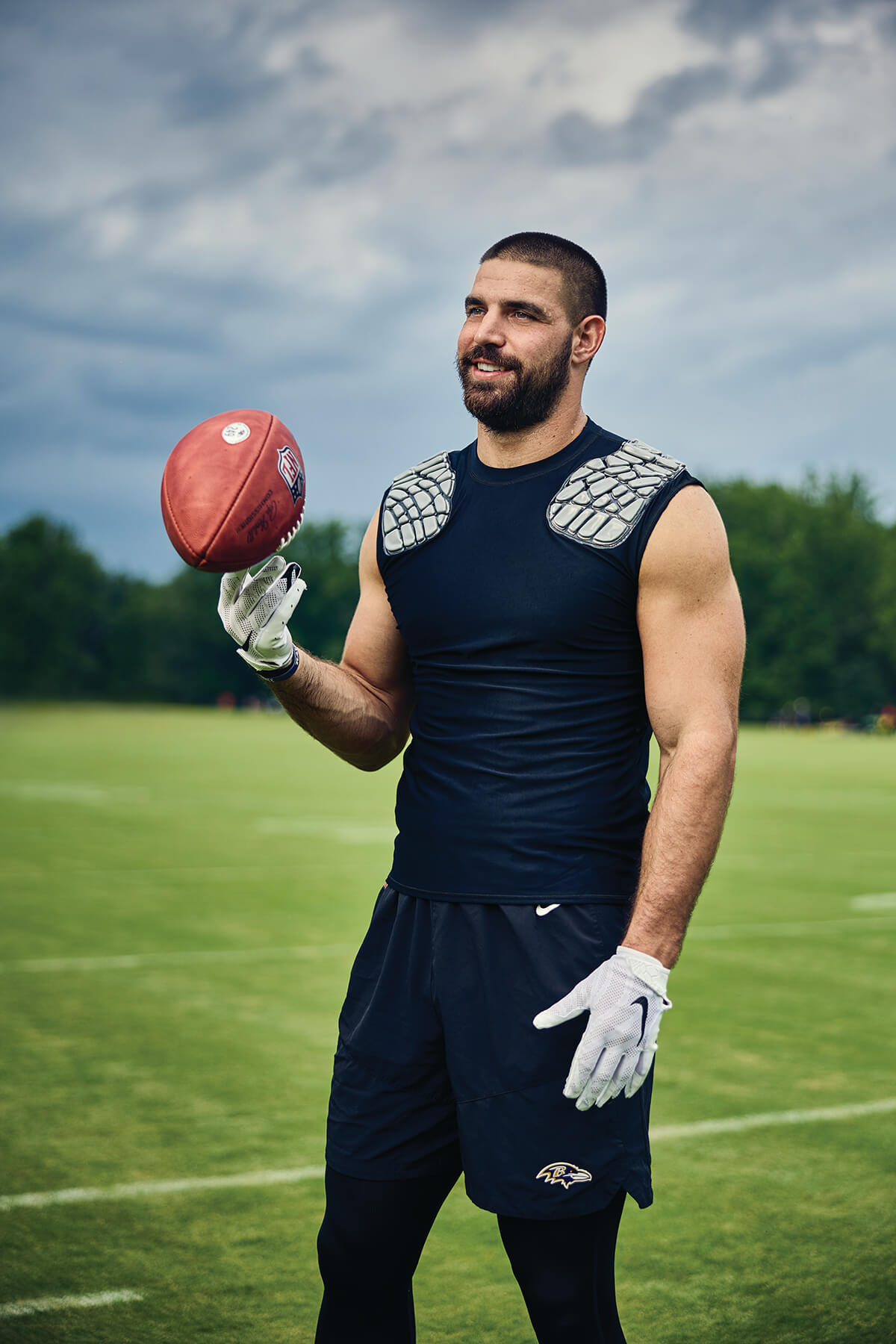

Andrews’ disease does not define him: He’s a devoted son and brother, a hard worker, and a loyal teammate first. Last season, his 107 catches and 1,361 receiving yards led all NFL tight ends. Both were franchise records. He established himself as quarterback Lamar Jackson’s go-to receiver, was named first-team All-Pro, and caught two touchdown passes in the Pro Bowl. What might come next for the 6-foot-5-inch, 256-pound star keeps defensive coordinators up at night. At 26 years old, he’s just entering his prime.

But whatever the future holds, Andrews will navigate it while wearing an insulin pump and continuous glucose monitor (CGM) on his hip. Most fans don’t realize the extent to which the disease must be managed on a daily basis. The Dexcom CGM is connected to Bluetooth, which goes to his parents’, brothers’, and trainers’ phones, enabling them to see his glucose levels in real time. (They say he usually handles it on his own—eating sugar if it’s too low and taking insulin if it’s too high—but if not, they text him.) It also connects with his Tandem pump, which automatically administers insulin to him if he needs it. “Almost like your own pancreas,” he says.

Andrews switches out the Dexcom every 10 days. The pump must be reset and its insulin replaced every three days. Since being diagnosed 17 years ago, diabetes has been an inescapable part of his life. Just because he’s reached such lofty athletic heights, that hasn’t changed.

“Being a diabetic, there’s more to think about than just being a regular person,” he says. “It takes more effort to be hydrated, to eat the right things. It’s no easy thing. You just gotta do what you gotta do. I’ve taken that motto and I’ve applied it to almost everything in life. Whatever life throws you, just go on and handle it.”

As he’s proven throughout his career, if someone throws something at Mark Andrews, he almost always catches it.

Growing up in Arizona, Andrews was the most athletic kid in a family full of athletes. The youngest of four, he had boundless energy, be it on the playground, the baseball diamond, or the soccer field. His mother, Martha, recalls dropping him off at school one day when he was in kindergarten or first grade. From there she went to the grocery store, where her cell phone rang.

“It was a call from my home phone,” she says, which was odd because no one was home. “I answered and Mark goes, ‘Mom, will you come take me to school?’ I said, ‘I already took you to school.’ He goes, ‘Yeah, but I left my library book, so I ran home because I didn’t want to get in trouble.’” The school was 2-and-a-half miles from their house.

When Andrews started playing soccer, he was a star from day one. The game came naturally to him, and on the field, he had a seemingly endless motor. If there was an injury timeout, his mom says, he’d drop to the ground and start doing push-ups. Which is why when his grandmother noticed him becoming lethargic and taking frequent bathroom breaks during a baseball game one day, she got worried.

“Mark would never leave a game to go to the bathroom,” Martha says. “We picked him up from that game and took him to a soccer game and he had to run off the field to go to the bathroom that time too.”

A few days later, his father, Paul, a urologist, took him to the doctor. When the diagnosis came in, his parents were devastated.

“I remember sitting in the waiting room, and the nurse and doctor coming up to us and letting us know that I had Type 1 diabetes,” Mark says. “Being that young, you don’t understand, but seeing my mom and dad cry, I knew something was going to change.”

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease in which the pancreas stops producing insulin—a hormone the body needs to get energy from food. People with the condition must artificially manipulate their blood sugar levels through insulin and food intake. It’s a never-ending dance that requires vigilant attention.

Andrews was just nine years old when his family began carefully monitoring everything that went into his body. “There are a lot of calculations that go on with diabetes. Figuring out what they’re eating, what they need to get through the day. I still don’t like to talk about what the long-term complications are,” Martha says, her voice wavering.

AS HE’S PROVEN THROUGHOUT HIS CAREER, IF SOMEONE THROWS SOMETHING AT MARK ANDREWS, HE ALMOST ALWAYS CATCHES IT.

In the years after his diagnosis, Andrews began giving himself shots. Because he lacked body fat, he would bend over, squeeze his belly, and insert the needle there.

“He never really said, ‘Why me?’” Martha says. “He didn’t ask a whole lot of questions. Bottom line was he understood that if he didn’t do it, he was going to die.”

There were hiccups along the way. Once, after eating too much buttered popcorn at a movie, he collapsed in the kitchen. Martha, who always kept sugary foods in the fridge, rubbed frosting on his gums and forced Gatorade down his throat.

As life settled into a new normal, Andrews’ athletic career continued to thrive. He started traveling around the country playing club soccer. Other teams took notice of the tall forward who was a prolific goal scorer.

“It got to a point where I’d have two or three kids shadowing me the whole game,” he says. “They’d hack at my ankles, and I’d get frustrated. I started getting red cards. My parents thought I needed to play something that was a little more physical.”

Following in the footsteps of his older brothers, Andrews joined the high school football team.

“He was skinny, but he had talent,” says Kelly Cook, his high school offensive coordinator. “His tenacity and grit are what I noticed right away.”

In his first game, Andrews caught a pass for a touchdown and returned a kick for another. By his sophomore year, he was being recruited by colleges. By his junior year, he was a star receiver catching bullets from teammate and future NFL quarterback Kyle Allen. Every college program wanted him. But while most coaches saw his future as a tight end, Andrews was determined to play wide receiver. He signed with Oklahoma—which promptly redshirted him (which allowed him to practice, but not play in games) and switched him to tight end.

It worked. The quiet but determined Andrews accepted the move and dove into learning the intricacies of the new position. By his third season, he was one of the best players in the country. He won the John Mackey Award, named for the late, legendary Baltimore Colt and awarded annually to college football’s most outstanding tight end. Feeling he had nothing left to prove, Andrews decided to forego his final season with the Sooners and enter the NFL draft.

Surprisingly—at least to him—Andrews’ name wasn’t called until the third round. Even crazier, the team that took him, Baltimore, had selected another tight end, Hayden Hurst, with its first-round pick. Andrews was angry—not at the Ravens, but at everyone who overlooked him.

“I think he was extremely honored that Baltimore selected him, but I think it was a chip for him,” says his brother Charlie. “It was, ‘I’m going to go there and prove them wrong.’ He’s done that his whole life. He’s always been doubted, but he always achieves more than people think.”

“HE’S ALWAYS BEEN DOUBTED, BUT HE ALWAYS ACHIEVES MORE THAN PEOPLE THINK.”

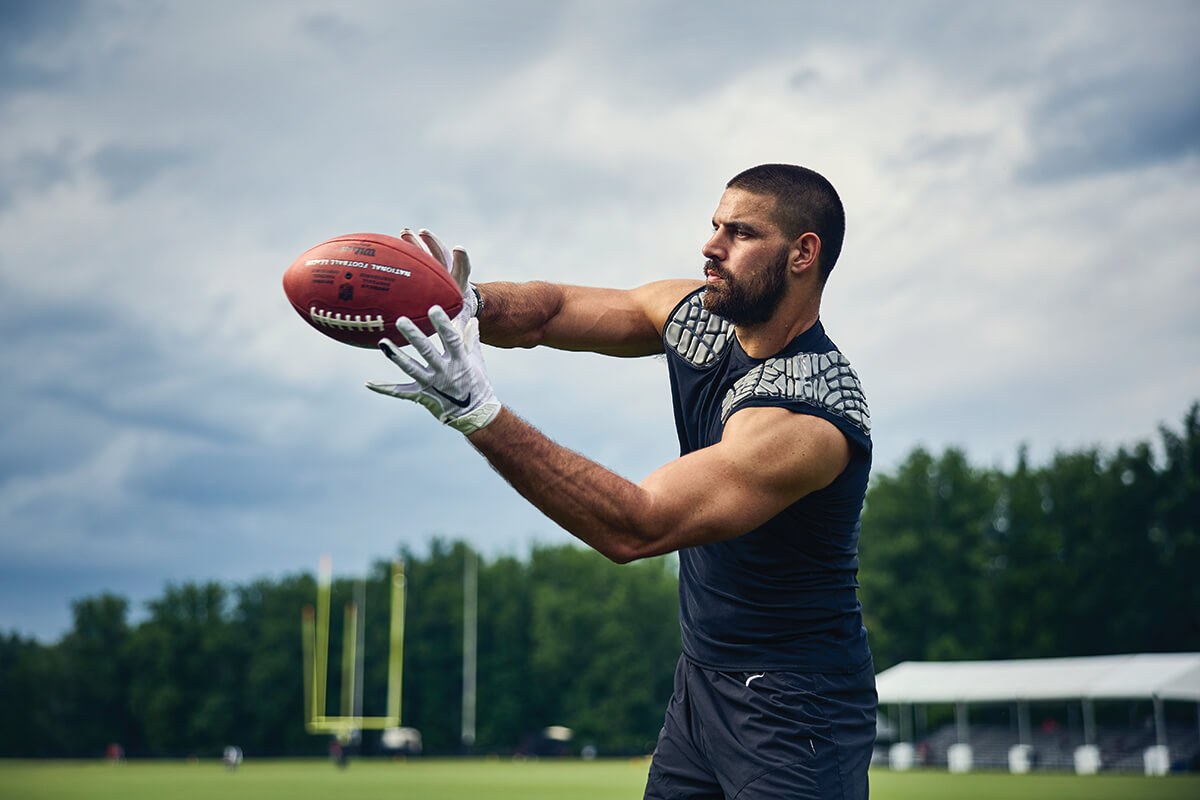

Before this June practice begins, Andrews warms up by casually snatching footballs moving very fast out of midair with an almost second-nature ease. For one of the best pass catchers in the game, that’s not exactly big news. However, on this day, three months before the 2022 season opener, the person throwing those balls is. Jackson, the quarterback with whom he’s developed intense chemistry, is not here. Still mired in ongoing contract negotiations with the team, the former MVP has chosen to skip this organized team activity (OTA). (Jackson did, however, attend the Ravens’ mandatory camp later that month.)

Andrews isn’t worried about Jackson, whose work ethic he praises effusively. Both were taken by the team in the 2018 draft, and their on-field bond was instantaneous.

“I remember rookie minicamp, we hit it off perfectly,” Andrews says. “The way that he sees the game is very unique. It feels like every time I was able to look back at the ball and cut a route short, he would see me. He’s been like that from the start. That connection you don’t have with everybody. That’s my quarterback. There’s a special place in my heart for him.”

Results came early. With the Ravens trailing the Chargers in the third quarter of a game that first year, Andrews streaked down the middle of the field. Jackson hit him for a 68-yard touchdown.

“He hit me perfectly in stride,” Andrews recalls. “We hadn’t been throwing the ball a bunch that game but being able to hit at the right time and the right place, that’s what football is all about.”

The respect between the two extends beyond the field. In the summer, the NFL tweeted a list of top five tight ends according to the Las Vegas Raiders’ Darren Waller. Andrews was listed as number five. Jackson apparently saw the tweet and responded by posting, “Mark @No. 5???” He added a laughing emoji for good measure.

Andrews routinely defends his quarterback against the loads of criticism that he describes as “nonsense.”

“If you know Lamar, if you’re around him every day, you see the way that he works and cares for the city and his teammates, this organization, you know that he’s all in,” Andrews says. “He’s said it from the beginning: ‘You’re going to get a Super Bowl out of me.’ And he means that. He’s hungry, he’s ready. To all the haters out there: Go away. Leave the man alone.”

Before these OTAs, Andrews spent most of his offseason at home in Scottsdale, where he lives with his brother Charlie in a four-bedroom home he bought prior to signing a four-year, $56-million extension in September 2021. After the season ends, the brothers have old friends from high school over to what their mom calls the “bachelor pad,” to swim in the pool, play Call of Duty, or grill out back.

“His personality is so humble,” says Cook, with whom he’s still close. “He has this big body and he’s a superstar, but he doesn’t flaunt it. That’s one of the things that makes all the moms of the girls he dates love him. My wife loves him.”

As the off-season progresses, Andrews becomes all business. He usually works out at his outdoor home gym six days a week, then runs routes and catches balls at the local high school. His excellence is no accident.

“When the ball’s thrown, you’ve got to get open and you’ve got to catch it,” says Ravens tight ends coach George Godsey. “I know it’s very simple to say that, but there’s a ‘route tree’ that he has that’s very diverse. Mark can run every route. He loves it and he works hard at it.”

Maybe that’s because he appreciates it just a little more than a guy who hasn’t been through what he’s been through.

In May, Andrews and his mom again put together a team for the JDRF One Walk. Since he began participating in 2019, his team has raised nearly $76,000 in support of Type 1 diabetes research. Andrews spent much of the day talking with fans, signing autographs, and posing for photos.

“Even with all of Mark’s incredible success, he shows such compassion and genuine happiness to connect with kids,” says Michael Simoni, executive director of the JDRF Desert West Chapter. “As his mother, Martha, affectionately says, ‘The kids are his peeps, and he just loves being around them.’”

A business administration major in college, Andrews isn’t sure what he wants to do after football. As last season demonstrated, he has plenty left to achieve in the game. What he does know is that he’s blessed to be part of a tight-knit family, a top-notch football organization, and to be in a position to help others with the disease he’s proven doesn’t have to slow you down.

“I want to make an impact in Type 1 diabetics’ lives,” he says. “The ultimate goal is being able to have that belief that one day we’ll be able to find a cure for Type 1 diabetes. I wholeheartedly believe that we will.”

He pauses for a moment, then adds: “It’s going to be a team effort.”