Health & Wellness

Brain Trust

One hundred and twenty-six years after opening, Sheppard Pratt Health System gets a new director and honors its past in the present.

Sitting in an office at The Forbush School at Glyndon, Sophie Rosenbloom’s sunny disposition floods a room that’s already bathed in natural light. After years of struggling with dramatic mood swings and self-destructive behaviors, Sophie has emerged from the darkness—“the shadows” as it’s sometimes called—into a brighter emotional space. With her long, lustrous hair the color of corn silk and shimmering hazel eyes, the 19 year old seems the picture of health. Her only physical imperfection is revealed when she rolls up the sleeves of her blue and pink flannel shirt, which hide dozens of small scars that run up her arms, like notches on a bedpost, the result of cutting. “Most of them are on my legs,” she’s quick to point out.

Sitting in an office at The Forbush School at Glyndon, Sophie Rosenbloom’s sunny disposition floods a room that’s already bathed in natural light. After years of struggling with dramatic mood swings and self-destructive behaviors, Sophie has emerged from the darkness—“the shadows” as it’s sometimes called—into a brighter emotional space. With her long, lustrous hair the color of corn silk and shimmering hazel eyes, the 19 year old seems the picture of health. Her only physical imperfection is revealed when she rolls up the sleeves of her blue and pink flannel shirt, which hide dozens of small scars that run up her arms, like notches on a bedpost, the result of cutting. “Most of them are on my legs,” she’s quick to point out.

Living in New Zealand, where she was born, Sophie was first diagnosed with depression in June 2012. A family move to Baltimore the following month offered the promise of a fresh start. But on her first day at Catonsville High School, she recalls, “the only person who spoke to me was asking to borrow a pencil.” Back in her bedroom later that day, feeling alienated and alone, she returned to her self-soothing coping mechanism. “Cutting myself took the inside pain to the outside pain,” she says. “It distracted me.”

That night, she emerged from her room badly bleeding and asked her mother for help. Her mom drove her to the emergency room, and they spent three nights waiting for a bed to open at Sheppard Pratt at Ellicott City, where Sophie was then hospitalized for what would become the first of nine times. After two years, Sophie was diagnosed with bipolar illness. “If you got a piece of paper and pressed down really hard and it indented the paper, and you’d scribbled until it was a big mess—that’s what bipolar illness feels like,” she says staring down at her pink Crocs. “Some holes are deeper than others.”

THE Historic “a” BUILDING ON THE TOWSON CAMPUS. Sophie ROSENBLOOM and her mother, MAUREEN, on the lawn at Sheppard Pratt.

Weeks later, on a sunny day in late April, Sophie’s mother, Maureen Rosenbloom, parks her minivan in front of a Federal Hill coffee spot. Two oars stretch from her front seat to the back and seem to dwarf the diminutive strawberry blonde, who is small but strong, the sinew in her arms apparent through her Baltimore Rowing jersey. “Rowing and yoga are part of my self-care,” she says. Rosenbloom is no stranger to pain, the kind “where you’ve been crushed, where you’ve been shattered, where you’ve been beaten down and are a puddle on the floor,” as she puts it.

Sophie can’t remember everything that happened while in the midst of psychosis, but Rosenbloom was a witness to it all. “For four years, my biggest fear was that she wouldn’t survive,” she says. Sophie’s care, marked by visits to Sheppard Pratt and other treatment centers every few months and a slew of drugs that only seemed to worsen her symptoms, was trial and error. “And the stakes were so high,” says Rosenbloom. “It rocked my world that mental illness could devastate an individual for so long that she wanted to die.”

“I’m trying to help get mental illness out of the darkness.”

Though several years have passed since Sophie’s darkest days, Rosenbloom still seethes with anger when she recalls that period of their lives. “I don’t have a censor button,” she says. “I put it all out there.” Particularly trying was the fact that, due to insurance restrictions, Sophie would get sent home from the hospital while still deep in the throes of her illness. And while Rosenbloom understood that the hospital’s hands were tied, she also found it hard to accept and railed against the system as it has been set up. “At Sheppard Pratt, they had no remorse,” she says. “Sophie was coming into the hospital every three months. I would say, ‘This is unbearable. Please don’t send her home,’ and they’d say, ‘There’s no medical necessity.’ They would pat my hand, saying she doesn’t meet medical necessity, insurance won’t allow it, add this med, bump this med up, keep this one as is.’ They’d say, ‘Bring her back if she is at risk of harming herself again.’” Rosenbloom says that discharge days were a murky mess of fear, powerlessness, and anger.

Back at home, Rosenbloom did all she could to support her daughter. “Her mania was rage,” recalls Rosenbloom. “She was like a fire-breathing dragon. I don’t know how I continued to express my love for Sophie except by pure staying power. I showed up. Every day. Every night. With the dark before us and the dark behind us.” But Rosenbloom also came to grips with the limits of motherly love. At the outset, she says, “People said, ‘You can’t fix this. Love is not enough.’”

It wasn’t enough, but ultimately it was a powerful part of Sophie’s recovery and something she also received at The Forbush School (formerly known as Hannah More) in Reisterstown, one of 12 special-education schools under the auspices of Sheppard Pratt Health System. Thanks to ongoing therapy, the correct cocktail of medications, and TLC from the school’s staff, Sophie got better and better. “She saw she wasn’t the only kid with a flat tire,” says Rosenbloom. “The people there touched her life and loved her back into wellness.”

SHEPPARD PRATT FOUNDER MOSES SHEPPARD; PHILANTHROPIST ENOCH PRATT and DR. Harsh Trivedi, president and ceo of sheppard pratt.

When Moses Sheppard—who was a Quaker, not a clinician—founded the institution that would become Sheppard Pratt in 1853, he adopted a radical idea about the care of the mentally ill that combined medicine and science with the notion of love.

“According to the Quakers, every individual has a light within,” says psychiatrist Steven Sharfstein, Sheppard Pratt’s former president and CEO. “Everyone is equal no matter how disordered they may be—you have to recognize that and treat people as human beings with dignity and respect.”

Walk through the halls of Sheppard Pratt, and you’re likely to run into a pair of paintings of Moses Sheppard and his co-founder, Enoch Pratt, whose presence continue to permeate the place. “That’s ‘Mo’ and ‘The Big E,’” says chief of staff (and resident jokester) Tom Hess as he passes through the lobby of the Weinberg building on Sheppard Pratt’s Towson campus. “Once you’ve been working here for more than 25 years, you can call them that.” Hess, in fact, has been at Sheppard for 48 years and has worked just about every job, from special-education teacher to director of support services. “I didn’t come here to be here forever,” says Hess, welling up. “I’ve just met some wonderful people, so I’ve stayed.”

The medical staff.

Moses Sheppard once remarked that if his $571,000 bequeath (the equivalent of about $15 million today) could help just one person, he’d be content. But it’s unlikely that he could have dreamed that what was first founded as an exclusive enclave for the affluent and a hospital for the mentally ill would become the largest single nonprofit provider of mental health care and support services in the country, serving some 80,000 visitors a year. Today, Sheppard Pratt offers mental-health services from the most acute, inpatient hospital services to community care for chronic issues such as schizophrenia and autism. “Moses Sheppard set the bar very low,” says Harsh Trivedi, a pediatric psychiatrist and the new president and CEO of Sheppard Pratt Health System, who arrived here from Nashville last year after a stint as head of Vanderbilt Psychiatric Hospital. “I think he’d be very happy to see how far we’ve come—and that we’re still working on the same mission.”

In Towson alone, psychiatric services offered by the insitution have grown to include an eating disorders unit, a trauma disorders unit, an adult inpatient hospital, a children’s inpatient hospital and intensive outpatient services. Consistently ranked one of the nation’s top psychiatric hospitals by U.S. News & World Report, the health system remains on the forefront of therapies, and was one of the first places to participate in the pivotal trial that led to the approval of transcranial magnetic stimulation (a new state-of-the-art treatment for depression) by the FDA. Also in the works is a plan for a new 85-bed hospital in Howard County scheduled to open in 2020 that will help alleviate the increasing shortages of psychiatric beds throughout the state.

“Nationally, Sheppard Pratt is one of the leading places to advance behavioral healthcare,” says Linda Raines, CEO of Mental Health Association of Maryland.

A “winter garden” in the solarium offered a place for quite contemplation. A Tiffany-style stained glass window. When the hospital was first under construction, they planned to heat the buildings by fireplace. But by the time they were finished 30 years later, coal furnaces had been invented. So, none of the fireplaces have ever been used.

Today, mental illness is increasingly seen as a disease to be treated much like any physical ailment. But it wasn’t always like that. At a time when “lunatics” in Maryland—and across the country—were confined to horrific conditions in cages, attics, and basements, or languished in almshouses or jails, along came Sheppard Pratt, with its specimen trees and sweeping front lawn leading visitors to a series of structures designed by famed 19th-century architect Calvert Vaux, who co-designed Central Park. The buildings, now on the National Historic Registry, were made of burnished bricks baked on the grounds and comprised of two six-story towers with intricate latticework, wide front porches, and Tiffany-style stained glass that still stand today. “At Sheppard, the word ‘mental’ is in ‘environmental,’” notes Sharfstein. “The dignity and the beauty of the setting where we take care of others have always been very important.” From its founding, Sheppard Pratt set itself apart in its approach to compassionate care of the mentally ill, a fact that 41-year-old Trivedi takes great pride in sharing. Sitting in his well-appointed office in the A building on the grounds in Towson, Trivedi shares a story that makes him smile. “Apparently, a few years ago, we had some people come through and say, ‘We are collecting historical pieces,’” he recounts. “They said, ‘Can you give us your original shackles?’” He shakes his head. “We are a psychiatric treatment center that never used shackles—that’s what differentiates us. That is not our history.”

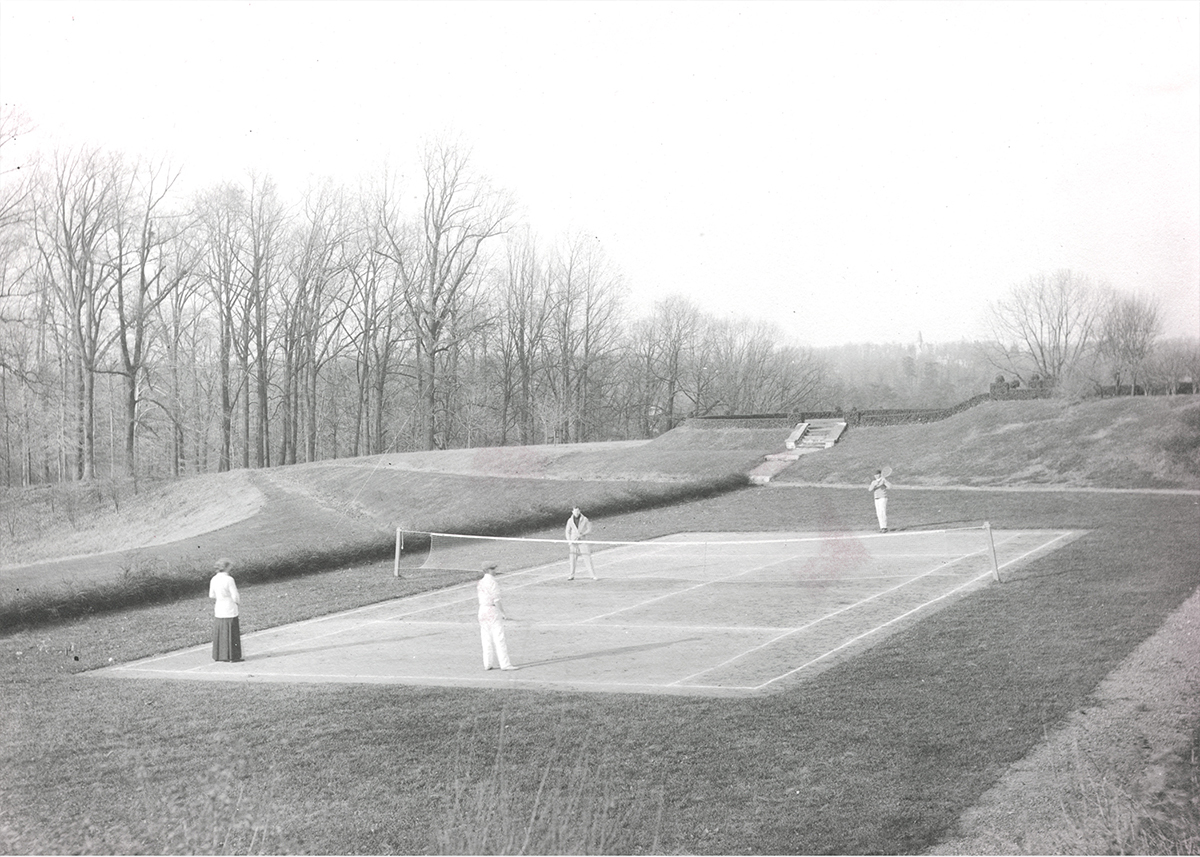

Baseball, basketball, tennis, wrestling, and bowling were all considered therapeutic activities for mental health patients. Occupational therapy was invented at Sheppard Pratt.

Moses Sheppard was born in 1775 and made his fortune in the dry-goods business. In accordance with his Quaker faith, the forward-thinking philanthropist had a passion for social causes and served as warden of the city’s poor and commissioner of the prison. It was there that he was first exposed to, and horrified by, the inhumane treatment of the mentally ill. Sheppard chartered The Sheppard Asylum in 1853 and, when he died in 1857 with no natural heirs, he left his entire estate of $571,000 for the building of the new hospital. At the time, it was the single largest bequest made to any mental-health institution in America. Given his stipulation that “it is the Income, not the Principal, of the Estate that is to sustain the Institution,” the asylum officially opened in 1891, 34 years after Sheppard’s death, on a 341-acre farm just north of Baltimore City. The building of the facility was so slow going that the construction of the hospital became a local one-liner—a motto around town for procrastinators was, “When the Sheppard is finished, I’ll do it.” With an additional $1.6 million bequest from philanthropist Enoch Pratt, the institution continued its growth in 1896 and was renamed The Sheppard and Enoch Pratt Hospital. It immediately set itself apart.

“There’s a dignity to getting care here that you don’t normally feel,” says Trivedi. “Moses Sheppard knew that. He specifically stipulated that not one patient room would be in the basement. It was about restoring dignity and respect. He believed that care should be provided compassionately.”

The first patient who was treated was a 46-year-old woman said to be suffering from dementia. She was admitted on December 6, 1891 for a cost of $2 per day. (Today, patients continue to be admitted to Sheppard Pratt regardless of ability to pay, including more than half who have Medicare/Medicaid.) Outdoor walks, a structured schedule—including meaningful work such as maintenance and housekeeping—games, a balanced diet, plenty of sleep, and always a minimum of restraints were used as part of the protocol. Most of the staff lived in suites alongside their patients.

“EVERY INDIVIDUAL HAS A LIGHT WITHIN. you have to recognize that and treat people as human beings.”

Sheppard Pratt quickly became a model for mental healthcare along the Eastern Seaboard, attracting some of the most famous doctors of the day, including Harry Stack Sullivan, then a world authority on schizophrenia and psychoanalysis, who arrived at the hospital in 1923.

Famous patients came for stays, too. Among the most well-known was Zelda Fitzgerald. In a June 14, 1934 letter to her husband, F. Scott Fitzgerald, she wrote: “For some reason, I’m very attached to this countryside. I love the clover fields and the click of baseball bats in the deep green cup of the field and the sky as blue and idyllic as parts of your prose.”

Throughout its history, Sheppard Pratt has been home to many firsts. It offered the first accredited training program for doctors and nurses in mental healthcare. It’s where Dr. William Rush Dunton coined the phrase “occupational therapy” (OT) and it was the first place to offer patients activities, including basket weaving, billiards, and bowling. Patients even had their own baseball team (so popular, the roster was seeded with semi-professionals).

“For someone like me, who is passionate about mental health and its treatment, it’s almost like dying and going to heaven in the sense you’re walking on grounds that are hallowed,” says Trivedi, who came to the main campus for the first time during his job interview in January 2015. He hopes to follow in the footsteps of giants. Only the sixth to serve as Sheppard Pratt’s director in its 126-year history, Trivedi strives to improve understanding and treatment of mental disorders as the institution leads the charge to set up the first-ever mental health registry in conjunction with the American Psychiatric Association.

Occupational therapy for female patients included weaving on a loom.

“So many of these registries exist for other disorders,” he explains, “but there’s nothing in mental health. So for something like depression, for instance, we would harness this information and look at it, based on other people like this particular patient all across the country, and ask should the treatment be lithium or Tegretol? Given our history, we had to be the ones to move that forward.” The landmark registry is set to roll out in the coming months.

Trivedi’s other initiative is to provide not only help, but hope. “When someone gets diagnosed with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, or has a first psychotic break, it’s the moment when everyone wants to push them away,” he says. “I’m trying to help get mental illness out of the darkness. I want people to have the same hope that you get when you walk in for your cancer care or for any kind of care that you get, because the vast majority of what we do is truly effective and helps people live meaningful, productive lives beyond what the diagnosis is.”

The Sheppard and Enoch Pratt Orchestra makes music. Several members were occupational therapists.

Even in places where hope is in short supply, like a rundown stretch of North Charles Street that hosts several methadone clinics, there is some cause for optimism thanks to Sheppard Pratt. John, who prefers not to use his last name, has suffered from severe mental illness with psychotic features for the better part of his 57 years and has been a member of Sheppard Pratt’s Mosaic Chesapeake Connections community program for nearly two decades. His mental health history includes many years of languishing in and out of three different state mental hospitals, including Spring Grove in Catonsville and the maximum security Clifton T. Perkins Hospital Center in Jessup, primarily reserved for patients who have been accused of felonies but are not fit to stand trial. “I was with violent people wearing helmets who hit their heads on the walls and they were kept drugged so they wouldn’t act out,” he recalls. He’s not able to fully explain what got him there, except to say that he recalls making it almost to the top of the 17-story George H. Fallon Federal Building in Baltimore. “I wasn’t trying to kill myself,” he says, “but I had climbed to the ledge and was looking down before they came and got me.”

At Chesapeake Connections one morning in June, John sits at a table socializing with other members and enjoying a warm cup of coffee. With most of his family members deceased, there is no one to help him with the daily tasks of living. But here, he says, “It’s like family—it’s a home away from home. They bought me soap, they helped me with hygiene, and got me clothes to wear. I come here three times a week and we all help each other out.”

“The brain is a complicated organ and the way it works is still a mystery.”

Of the program’s 150 or so members, only 11 have been hospitalized in the past year, an incredibly low number for this patient population that is among the most disadvantaged and severely ill in the city. The specially funded program, one of two in the state, “pays it forward,” allotting $2,400 a month per person, says program director Denise Chatham, who came to Chesapeake Connections from Walter Reed National Military Medical Center 14 years ago. It is a model program for the state because it takes a prophylactic approach to mental healthcare. It helps those afflicted by recognizing and providing basic necessities—from food to rent assistance—and a support system, which is vital to keeping members as independent as possible.

“This model is the world’s best model given the fact that it really keeps people living a life, whether it’s helping them get to school or helping them find volunteer or paid work,” says Chatham. “If not for this program, our members would be on the street or in jail.”

Patient casebook from 1891 to 1900.

While great gains have been made in mental healthcare, the picture is far from rosy for the tens of millions of people who suffer from mental disorders, only about half of whom actually receive treatment, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. For those in treatment, there are still no easy answers, as is evident with the treatment of Sophie’s illness. “We have better treatments today, but they’re still halfway technologies,” acknowledges Sharfstein. “The brain is a complicated organ and the way it works is still a mystery—we’ve made strides in the understanding, and the neuroscience is growing by leaps and bounds. At some point, we will be able to transplant every organ in the body, but not the brain. The treatments are crude. There are no cures—we help the symptoms.”

Of course, the care can be as quixotic as the drugs—and the issues are manifold. The deinstitutionalization of the mentally ill that began in 1963 when President John F. Kennedy signed the Community Mental Health Act was supposed to provide effective treatment in the least restrictive setting, but caused its own set of problems. “Up until that time, people had been warehoused in the most deplorable conditions. The idea was to put money into community treatment centers,” says Mental Health Association of Maryland’s Dan Martin. “But it never really worked out that way.” Nowadays, with no treatment, people often end up on the streets and in trouble with the law, driving those who need the care to the criminal justice system instead of the public health system, which is where they belong.

“The jail is now replacing the institutions,” says Mosaic president and chief executive officer Jeff Richardson. “The largest mental healthcare facility in the United States is still the Cook County Jail in Chicago followed by the L.A. County Jail.” Weighs in Sharfstein, “Every Christmas, [the late] Byron Forbush, [Sheppard’s former chairman of the board] and I would lay a wreath on Moses Sheppard’s grave at Greenmount Cemetery,” he says, “and talk about the changes that were happening and hoping that he wasn’t rolling over.”

Even when people are able to seek help before their illness leads them astray, the supply can’t meet the demand, as older doctors retire and fewer people are choosing psychiatry as a profession. “The Baltimore Business Journal did a study a few years ago,” says Sherry Welch, executive director of National Alliance on Mental Illness in Baltimore. “They looked at the referral books you get from insurance companies and, in mental health, [a large number] of physicians listed there were not taking new patients, were no longer practicing, or had moved out of state.”

“i’ve learned to coexist with my mental illness,” says sophie rosenbloom. “It’s not eating me alive anymore.”

Stigma remains an issue, as well. When, in 2011, Sheppard Pratt purchased the house that would become Ruxton House, a private-pay, group home in tiny Ruxton, Sharfstein recalls the outcry from the local community. Their public line was that they were worried about their housing values, but in reality they had more deep-seated concerns. “One of the quotes from a neighbor was, ‘We just don’t know what these people are thinking,’” says Sharfstein. “As if they know what any of the neighbors are thinking. We have hundreds of residences across Maryland and this was the worst NIMBY—Not In My Backyard—I’ve ever seen. There were lawsuits, there were demonstrations, but we hung in there and we built the home.”

Front of The Gatehouse. When the hospital opened, horse-drawn carriages would come through the center of the entrance.

Even hospitals have stigmatized the psychiatric population. “Without naming names, there are large hospitals in this community with only one psychiatrist on staff,” says Welch. “They don’t want mental-health patients. There’s no surgery. There are no dollars in it—it doesn’t pay.” And then there are the issues with insurance companies that don’t reimburse for mental illness in the same way they do for other illnesses. At Sheppard Pratt, for instance, at one time patients spent months, even years healing. (Fitzgerald stayed for nearly two years.) Now the average length of stay is three to five days on an inpatient crisis-stabilization unit. “Insurance companies give you like five days to get better from your schizophrenia,” says Chatham of Chesapeake Connections ironically.

It has taken years for Sophie to get the care that she needs. And while no one can say what tomorrow will bring, she’s in a good place for now. In June, Sophie graduated from The Forbush School and is currently taking classes at Howard County Community College, where she eventually plans to study neurobiology. “I’m so much happier now,” she says. “I don’t even know what happened—it just changed. I never thought I’d graduate from high school. I legitimately thought I’d be dead.” She gathers her thoughts, and then continues. “I really love my mom now, but I used to be very mean to her—it would make me feel better about myself. I wanted her to give up on me, because that would mean that nobody cared and I could leave in peace. I’ve learned to coexist with my mental illness, side by side. It has a presence, but it’s not over top of me. It’s not eating me alive anymore—I’m happy to be alive.”

Her mother is on her own road to recovery. And while her feelings toward Sheppard Pratt, the mental healthcare system, and her daughter’s disease are complicated, her gratitude is crystal clear. “As parents, we often think that our love is enough. It’s very important, but you also need help,” Rosenbloom says. She takes nothing for granted now. “There’s an awareness of when the smallest things go well,” she says, “and I’m aware of what a blessing that is. But when I drive past an ER that can be a trigger and send me back to really bad memories. But today, today was so beautiful, I got out on the water—and I was able to row.”