For years, the challenges faced by sex workers in baltimore went largely unnoticed. Now, a pioneering program empowers them to take back their lives.

News & Community

Hidden Figures

For years, the challenges faced by sex workers in baltimore went largely unnoticed. Now, a pioneering program empowers them to take back their lives.

By Kaitlyn Pacheco

Illustration by Laura Redburn

Photography by justin tsucalas

she was in middle school, and the man handing her cash was her teacher. She was 13 years old, with chestnut-brown eyes and a full, throaty laugh, and she felt like she didn’t have a choice. Her teacher had been molesting her for months, and the money he agreed to give her when they had sex bought her silence.

As time went on, the encounters—with him and other men who offered her money—started to feel normal. The West Baltimore middle schooler didn’t want to be at home, where she suffered abuse at the hands of her mother, and the men and their cash-in-hand offers delayed her return.

At 16, Alyn started smoking crack, and two years later, on New Year’s Eve 1984, she worked her first shift as an exotic dancer on The Block. Stripping on this notorious section of East Baltimore Street, known for its rows of neon-lit strip clubs and sex shops, seemed easy enough. After all, she had gotten used to people paying to see her, watch her, touch her.

But as Alyn’s addiction worsened, she started doing more for the club’s customers for less money. The Block, which had once represented opportunity—an escape—began to drag her under, and she couldn’t find her footing long enough to save money or say no. Without knowing it, she had fallen into the same cycle that would consume generations of women in Baltimore’s sex industry, and it would be decades before someone would recognize the pattern and offer help.

“When you’re a child, no one says, ‘When I grow up, I want to be a prostitute or an addict,’ but when you feel hopeless, things happen,” Alyn says today, using only her first name to protect her identity. “I wanted someone to see me, but back then, I couldn’t even see myself.”

susan sherman poses in front of portraits of some of sparc's visitors

usan Sherman can’t talk about the treatment of female sex workers in Baltimore without raising her voice. The professor in the department of health, behavior, and society at the Johns Hopkins University’s Bloomberg School of Public Health spent eight years of her career conducting the most extensive study of exotic dancers in the nation, documenting the experiences of 417 people working on The Block in Baltimore City but she still remembers the first woman who shocked her into action.

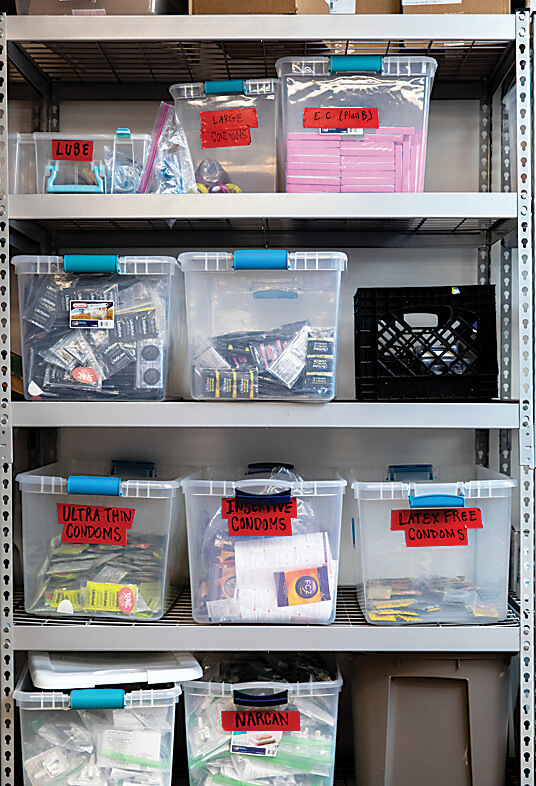

bins of harm-reduction supplies available at the center.

Back in February 2008, Sherman was working as a research partner with the Baltimore City Health Department’s needle exchange program when one of her colleagues got an anonymous tip about drug use and sex work by the dancers inside The Block’s clubs. By that time, she had spent years developing HIV-prevention programs in high-risk areas in places such as Thailand and India, and working with drug users and sex workers to understand how their vulnerabilities—from homelessness to addiction—made them more susceptible to risky behavior.

None of that prepared her for the meeting she attended at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, where a psychiatry patient who was recovering from a heroin addiction who had danced on The Block for several years drew a map of the clubs and detailed the illicit activities that happened inside each corner. “I was speechless,” Sherman says. “There’s completely illegal behavior happening in plain sight of everyone, and it’s the women who are suffering.”

Immediately after hearing the dancer’s story, Sherman started working with the city to send a needle exchange van to The Block, which is only one street away from police headquarters and City Hall. That spring, the resource van parked on the corner of Baltimore and Gay Streets for the first time—offering free contraceptives, sterile syringes, sexually transmitted infection testing, and overdose prevention training—where it still sits every Thursday night.

As an expert on harm reduction, Sherman stands by providing people with options, not telling them what to do. But she wanted to know more; she wanted to understand the impact of the illegal activity in clubs on the women who worked there. So that summer, she and a team of graduate students surveyed 100 dancers who visited the van, where 55 self-reported using heroin and crack inside the clubs, while 42 reported exchanging sex for money.

Although none of the women interviewed said they were forced into sex work, Sherman’s team heard enough firsthand accounts from dancers to understand how someone like Alyn would feel pressured to have sex with the club’s customers.

“That’s how they made the most money,” Sherman says simply. “Even though the women don’t touch the money, not until everyone else—bartenders, bouncers, managers—gets their cut.” Alyn remembers how, in order to fund her addiction, she would do anything that her bosses asked of her, settling for worse scenarios as time went on.

“Those things you say you’ll never do, they become true if you’re in there long enough,” she says.

After hearing the women’s stories, Sherman realized she needed to learn more about the ways in which the environment of the clubs and the common practices she heard about—such as “runners” delivering drugs to dancers mid-shift—put the women who worked there at further risk.

Known for her unapologetic methods of pushing through red-tape barriers, Sherman wanted to get inside the clubs—past the bouncers and managers—to find out what was really going on. In 2013, she began a two-year research project with funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse that surveyed 26 exotic dance clubs in Baltimore City and County to determine the risk factors of places where sex work occurs. The STILETTO Risk Assessment quantified the responses that employees gave about everything from the prevalence of drug use to safe sex practices and ranked each club from least to most risky. The team then spent six months monitoring 117 women who were new to exotic dancing to determine how their exposure to the clubs impacted them.

“We found that, yes, in fact, women working in higher-risk clubs had higher rates of selling sex and problematic drug use,” Sherman says. “Sometimes we have to prove the obvious, but it also gives voice to things that aren’t always obvious or an issue to everyone.”

“there’s completely illegal behavior happening in plain sight of everyone, and it’s the women who are suffering.”

With the study results in hand, Sherman realized the role she could play in furthering the public’s understanding of the daily challenges of female sex workers. After all, no one else was asking them questions, let alone studying how their jobs affected their health and well-being. “[Researchers] don’t talk about street-based female sex workers or women who use drugs,” Sherman says. “It’s my responsibility to create [a body of] evidence to effect change; it’s why I do what I do.”

In April 2016, Sherman launched another long-term study, this time of 310 local female sex workers, to examine another prevalent issue—their interactions with law enforcement. The SAPPHIRE study, short for Sex Workers and Police Promoting Health in Risky Environments, investigated the sex workers’ encounters with police, including incidents of violence and harassment.

The results spoke volumes: 78 percent of participants reported experiencing at least one abusive interaction with law enforcement in their lifetime. Sherman’s team also found that the more abusive interactions that street-based sex workers have with police, the higher the risk for violence caused by clients.

Katelyn Riegger, who started as a research program assistant on the study, says that while SAPPHIRE’s conclusions were eye-opening, she also felt moved by many of the participants’ deep appreciation for the HIV and STI services and referrals provided during every data-collecting visit. As Riegger built a relationship with the women over the course of the study, she caught a glimpse at the massive impact that such basic health assistance had on their daily lives.

“Someone sent me a thank you card that said, ‘You’re the only people who are coming to our community and providing us with services,’” Riegger says. “We have people in our community who are begging for connections to help, so much so that even a research study filled that gap.”

But after years of documenting these struggles, Sherman had grown tired of watching at arm’s length. She recognized that most of the women’s gateway drug, if you will, was trauma, and while she couldn’t reverse how they had gotten hooked, she wanted to provide them with options and resources to reduce the harms of drug use and sex work.

After a decade of connecting the dots, she saw a clear and urgent need for a dedicated space where women and non-male sex workers could receive the services they needed to make safer, healthier choices—from showers and laundry to legal assistance and reproductive health care—as well as form connections with one another to bolster their individual and collective strength. “A drop-in center felt like the natural evolution of what we were doing,” Sherman says. “Creating a place where people can be seen, use the computer, get sterile syringes, and talk with a case manager, honestly, is priceless.”

Sherman received a five-year grant from the National Institutes of Health, along with grants from the Abell Foundation, and the Maryland Department of Mental Health, to do just that, establish one of the country’s first comprehensive, full-service centers targeted toward non-male sex workers. And, in November 2017, the SPARC Center—Sex Workers Promoting Action, Risk Reduction, and Community Mobilization—opened its doors in Pigtown, ready to make a difference.

bout two years ago, Cecile was walking down Washington Boulevard when she saw a building she didn’t recognize with pink lettering across its glass doors. When she stopped to read the sign, Riegger, now the clinical director of the SPARC Center, came to the door, explained that the center was new to the neighborhood, and invited her inside. Cecile, who was then struggling with a heroin addiction, couldn’t believe how inviting the center was in comparison to other local resource centers and homeless shelters.

bout two years ago, Cecile was walking down Washington Boulevard when she saw a building she didn’t recognize with pink lettering across its glass doors. When she stopped to read the sign, Riegger, now the clinical director of the SPARC Center, came to the door, explained that the center was new to the neighborhood, and invited her inside. Cecile, who was then struggling with a heroin addiction, couldn’t believe how inviting the center was in comparison to other local resource centers and homeless shelters.

With high ceilings, beams of natural light, and one-of-a-kind architectural details—thanks to the building’s previous life as a church—the center gives visitors a warm welcome even before the staff does. Women like Cecile can spend time in the expansive community space packed with couches and a TV, or visit the second floor for group activities such as book club, NA meetings, and “twerkshop” dance classes.

“I went there almost every day just to sit down and stay out of trouble,” Cecile says. “They let you come in, have a cup of coffee, and take a nap, which is pretty helpful for a lot of people.”

“creating a place where people can be seen, use the computer, get sterile syringes, and talk with a case manager, honestly, is priceless.”

When the center opened its doors in November 2017, Sherman and her team were prepared with a host of products and services specific to sex workers and other women in need, such as emergency contraception and HIV-prevention consultations, but they quickly learned that they needed access to even more basic assistance. In response to feedback from the community, the SPARC Center added a food pantry, a clothing closet, and industrial washers and dryers.

“Nobody cares about taking yoga classes if they don’t have pants,” Riegger says. “If their basic needs aren’t met—if their clothes are soiled or they haven’t showered—they can’t engage in or even think about higher-level activities.”

the harm-reduction van parked in pigtown.

But just as the foot traffic began to pick up at SPARC, the CityLink bus line that had been transporting visitors from farther afield neighborhoods like Curtis Bay and Brooklyn changed. Sherman and her team felt stuck; their target visitors in Southwest Baltimore didn’t have the time or means to make a three-hour bus trip to and from the center. They quickly formed an outreach team and went back to their roots, returning to the streets on foot and via van to hand out harm-reduction supplies to women in need. Now, three to four times per week, the SPARC van circles South Baltimore, stopping to allow people to “shop” for products like condoms, safe snorting and smoking supplies, and fentanyl-testing kits. It has also become a sort of message board on wheels, with visitors sharing information about “bad dates” or bad batches of drugs that the outreach team can pass along to other people in the area.

“On the outreach van, we can literally meet people where they are and give them whatever service they need, even if that’s just talking to someone,” says Katie Evans, the center’s outreach coordinator. “People are more comfortable on their own turf, and when we’re out in the community, we can meet people in any state, so there’s less pressure on them.”

Over the past two years, as the center’s client base has grown to about 80 visits per week, SPARC has earned the trust of the community, thanks to its reputation for being a place where women of all walks of life are treated with dignity and respect. Sherman says their work is not always pretty, and definitely not for the faint of heart, but the team prides itself on running a center that makes space for anyone who walks through the door.

the sparc center's team of staff members.

“Our expectations of people are very different than other organizations—we truly accept them in whatever form they’re in that day—good or bad, sober or not,” Riegger says. “We measure success differently, and we celebrate people for who they are.”

On top of having faith in the staff, visitors have to trust the other women who are watching movies in the community room or coming to the center to get sterile syringes. Previous studies show that social cohesion among female sex workers is typically low, but staff members say that the center has helped create new relationships among the women by providing a safe place to talk and bond through activities like dancing or reading together.

“There’s a powerful resilience in this building. We teach each other how to be strong and take those baby steps forward.”

For Alyn, who has been frequenting the SPARC Center since July, the women that she’s met there have done more than become her friends—they’ve kept her in recovery. She was in drug treatment at the Tuerk House addiction treatment center in West Baltimore when she first heard about SPARC. The day after she was released from treatment, she headed straight to Pigtown, and since then, she’s visited almost every day to meet up with friends and participate in weekly activities.

“It gives me a sense of family,” Alyn says. “We help each other through rough patches, and just coming around and socializing every day has helped me stay on track.”

As the center continues to grow to keep up with the needs of visitors, Sherman is also monitoring its progress as part of a larger study, dubbed “EMERALD,” examining whether sex workers who have access to SPARC have better outcomes than those who don’t live or work in the area. The new study will track the behavior of 385 women through 2022 to evaluate the center’s impact in South Baltimore with regard to HIV and STI rates, as well as social outcomes such as cohesion and empowerment.

As was the case with her previous research, Sherman hopes that the results from both SAPPHIRE and the new study, as well as testimony from SPARC visitors, will help move the political needle on issues such as decriminalization of sex work, a topic that has recently gained national traction. “You can’t come into this neutral; there’s a lot not to be neutral about,” Sherman says. “All the research that I’ve done is from the point of advocacy work, because the scientific rigor is meant to provide the evidence needed to make change.”

In the meantime, the SPARC team will continue their work, making a difference in the lives of women like Cecile, who hasn't used in more than a year, and Alyn, who plans to marry her partner of 11 years this September. “There’s a powerful resilience in this building,” Riegger says. “We teach each other how to be strong and take those baby steps forward.”

n a cold Friday in December, Alyn spent the morning in her South Baltimore kitchen making some of her favorite foods—fried chicken wings, vegetable pasta, and tuna pasta. Later that day, she brought the dishes, along with some colorful streamers and a banner, to the SPARC Center, where everyone —strangers, friends, staff members—gathered for her 53rd birthday party.

n a cold Friday in December, Alyn spent the morning in her South Baltimore kitchen making some of her favorite foods—fried chicken wings, vegetable pasta, and tuna pasta. Later that day, she brought the dishes, along with some colorful streamers and a banner, to the SPARC Center, where everyone —strangers, friends, staff members—gathered for her 53rd birthday party.

She wanted to start her next year surrounded by her true family, the women that make her feel lucky and proud to be alive. After all, it’s thanks in part to their support that she’s not only remained substance-free, but also found a new purpose in life—helping women who are struggling with familiar problems. This winter, she started taking courses to receive her peer recovery certification, and will begin classes later this year to become a community health worker.

That afternoon, the group spent a few hours laughing, dancing, and taking photos in the community room before cutting into dessert—a sheet cake with a picture of Alyn and some of her favorite SPARC staffers emblazoned in icing. “I feel like I can live again,” Alyn says, beaming. “I want to be a light in all of this darkness—that idea has given me something to live for.”