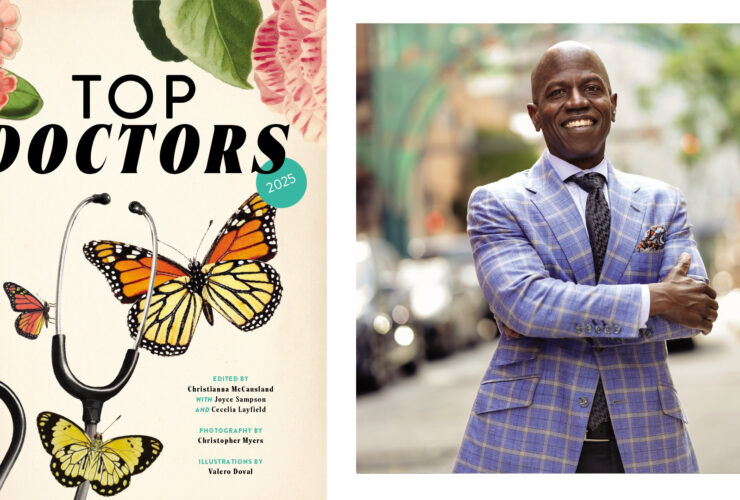

Health & Wellness

Mind's Eye

Without sight for nearly 60 years, Wilmer Eye Institute board chairman Sandy Greenberg aims to end blindness.

n Valentine’s Day 1961, his mother sat near the foot of his hospital bed and the light was almost gone. “Son,” the doctor had told him a day earlier, “you’re going to be blind tomorrow.”

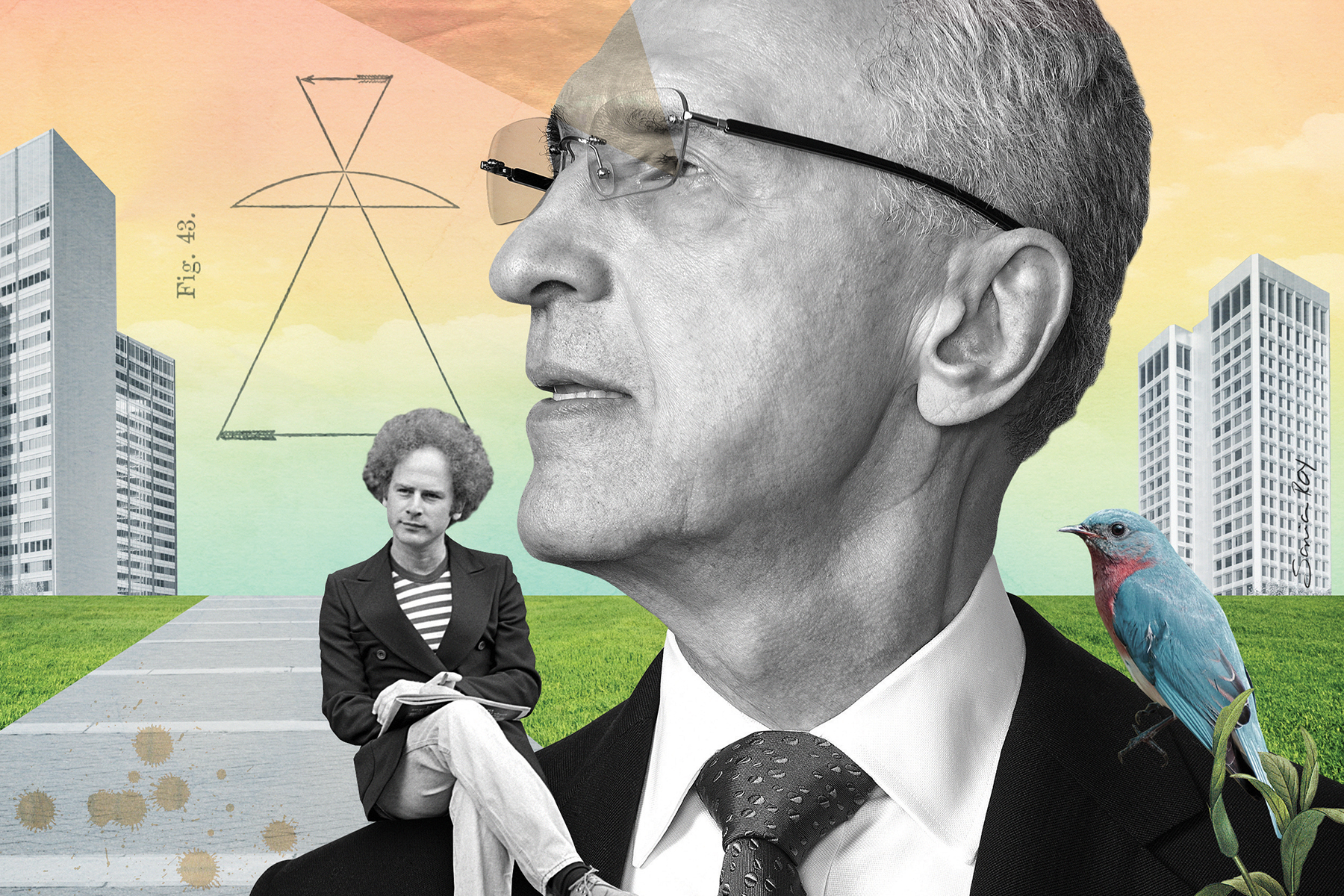

Sandy Greenberg was just 20 when he first heard those gut-punching words in a Detroit exam room, but they remain seared in his mind, just like the lasting image of his wife of 55 years, Sue. Or the memory of the patch of illuminated New York City grass that one of his college roommates and lifelong friends, Art Garfunkel (yes, him), pointed to freshman year and said “Look at what the light does to the color” during a walk on the corner of Amsterdam and 118th streets on Columbia University’s Upper West Side campus.

Everything else is a picture he has to paint in his imagination, like his three children and four grandchildren. Or his sense of the beloved Rembrandt that hangs in his Washington D.C. apartment. And, more recently, the presumed shocked expressions of board members and faculty at Johns Hopkins’ world-renowned Wilmer Eye Institute, when, six years ago, an impeccably dressed blind man who had grown up poor walked up to a note-less podium and issued an astonishing challenge. He eventually announced it publicly: The Sanford and Susan Greenberg Prize, $2 million in gold to whomever does the most to end blindness by the year 2020. This was his moonshot.

“This is our destiny,” Greenberg said. “End it, end it, end it.”

Greenberg with his Rembrandt in his apartment.

His story is a cruel irony and a fascinating paradox rolled into a remarkable life, powerful and inspiring enough to rally a group of the world’s top doctors and scientists, and undeniably audacious enough to garner the world’s attention.

Yes, Dr. Sanford Greenberg, chairman of the board of governors of one of the best eye institutes on the planet, is blind.

But you might not know it when you meet him. Standing just outside the door to his office in the Watergate building in D.C., without a cane or seeing-eye dog and dressed in a dark suit and purple tie, Greenberg is tall, well-built, and wearing glasses that rest near the graying hair at his temples. He offers a warm introduction and a firm handshake.

“You sit over there,” he says politely and deliberately, intimating a spot on the far end of a U-shaped white couch, “and I’ll sit over here.” As he does so carefully, a 1987 photo of him playing basketball against former Senator and New York Knick Bill Bradley comes into view over his left shoulder. “That’s what life is about,” he says. “You go beyond what you think you can do.”

This is a man who grew up in a blighted neighborhood of Buffalo—with a father who escaped the Nazis and died in America when Greenberg was 5, and a stepfather who ran a junk shop to provide for Greenberg, his mother, and three siblings.

He earned a full academic scholarship to Columbia University. During his junior year, he lost his sight because of a mistake. A doctor prescribed steroid eye drops for allergic conjunctivitis that, left unchecked, built pressure and fluid in Greenberg’s young eyes, destroying his optic nerves and giving him glaucoma. After days of dark depression, he emerged to live a rich and distinguished life. It was anything but the future of caning chairs or making screwdrivers that a social worker told him he was destined for.

No, after going blind, Greenberg graduated from Columbia, earning straight As that final semester and being elected class president. He earned an MBA there, too, and went on to attend Oxford on a Marshall scholarship. Later he earned a master’s and a Ph.D. in political science at Harvard, where he also attended law school for a year, leaving only to become a White House fellow in President Lyndon Johnson’s administration.

He has operated a variety of successful businesses—in science, technology, and real estate—and created a transcendent invention, a variable speech control device. Jonas Salk, who cured polio, once peppered Greenberg with questions about his creation, the first to compress and expand the recorded human voice while keeping it intelligible. Greenberg patented the idea in 1969, eight years after losing his sight. It was born from necessity as he sought to absorb information in more words per minute than Braille allowed, and faster than the speeds at which the volunteers that read books to him could speak. The founder and then-president of Sony thought enough to sign a contract for the rights to use the technology in tape recorders and cassettes, which made a poor, blind (but extremely smart) kid financially independent.

“People call them polymaths—somebody who can excel intellectually in many different fields,” says Dr. Peter McDonnell, a smart man himself and the director of Wilmer since 2003. “I’m jealous. I know his IQ is two to three times what mine is.”

If the roughly 40 million blind people living on Earth were to have their version of a Beethoven—the famously deaf composer—Greenberg might be it. Seven years ago, citing his business acumen and two decades-long relationship with Johns Hopkins, as a trustee emeritus for the university and Hopkins Medicine, McDonnell asked Greenberg if he wanted to chair Wilmer’s board.

“I’d think you want somebody that can see,” Greenberg replied initially, hesitant to be defined by his handicap, as so many fear. In fact, a Wilmer study published in October 2016 concluded that most Americans consider blindness the worst ailment that could happen to them, worse than losing a limb, memory, speech, or hearing—and for good reason. The Baltimore-based advocacy group, the National Federation of the Blind, estimates that 70 percent of blind people in the United States are unemployed.

“The primary problem that blind people have is low expectations,” says Chris Danielsen, the Federation’s public relations director for the past eight years, who was born blind. “We spend a lot of time combatting that.” Currently, more than 110,000 people in Maryland face partial or complete vision loss.

But Greenberg flies in the face of standard blind practice, declining to use a white cane, Braille, or a guide dog, and preferring to walk alone and asking for help only if he really needs it. He lives with his wife in a building adjacent to his office.

“That’s the way I maintained my dignity,” he says. “I know if I were to tell other blind people that’s the way I deal, they’d think I was ignorant. For other people to not have the good fortune that I have”—referring to a support system of family, friends, and business associates—“well, that kills me. That is one of the motivating reasons we’ve got to get rid of this wretched curse.”

The chances of survival for the blind and resources to correct vision dwindle significantly outside our borders. For instance, in India, the life expectancy for a child born blind is 2 years, Greenberg says. A 60 Minutes segment earlier this year profiled a pair of doctors who performed what Americans would think of as routine cataract surgery in order to return vision to more than 150,000 people in 24 countries, including far-flung Nepal.

If the 40 million blind people living on earth were to have their version of a beethoven, Greenberg might be it.

“It’s been 6 or 7 million years since our bipedal ancestors, and we humans, have been plagued by blindness, and nothing has changed,” Greenberg says. “That seems immoral.”

For several days after he went blind, Greenberg holed up in his bedroom. He took sleeping pills to escape the days, and shunned most visitors, save two: Sue, the love of his life, whom he started dating in tenth grade. (He thought she would leave him. “That never occurred to me,” she says. “No one should have to endure what he went through.”)

The other was his smart-alecky, big-haired friend Garfunkel. He wasn’t yet famous, and they were the original S&G. There’s reel-to-reel, rock-and-roll tapes from freshman and sophomore year to prove it; Sanford on drums, Garfunkel on guitar.

“I need you to come back,” Garfunkel said, ultimately convincing Greenberg to return to school, despite his family’s fears that he might be killed in Manhattan. “Arthur was primarily responsible for taking care of me,” Greenberg says. “He’d take me to class, to and from, take me around the city, fix my tape recorder when it broke, bandage my shins when I bloodied them.” And more.

One late afternoon, Greenberg could smell the grease from the subway platform in New York’s Grand Central Station. For a moment, he hoped a train would hit him, just to end it all. Garfunkel, who brought him back to school and read textbooks to him nightly, had just abandoned him after a heated debate. And now Greenberg was furious, alone, blind, and disoriented in one of the world’s busiest train stations. Rush hour was approaching. He knocked into a woman. He tripped over a baby in a stroller, and the mother yelled at him. “I wanted to be both dead and alive,” he says.

He managed to stumble into the correct train, make a connection and emerge near Broadway and 116th Street at Columbia's campus. “Oops, I’m sorry,” a man said as he bumped into Greenberg. It was the familiar voice of Garfunkel, who had followed him and purposefully set up the entire situation to show Greenberg that he can be self-sufficient.

“That episode defines me,” Greenberg says. “When I came out of the subway, I had a different worldview—no more doubt and fear.”

There is a reason why the Greenberg Prize to End Blindness will be paid in gold. It’s the color of one of Greenberg’s last sighted memories, a sunset stroll on the shores of Lake Erie that he shared with Sue. Several distinguished individuals make up the prize’s governing council. Among them is former U.S. attorney general Michael Mukasey, whom Greenberg was headed to meet the day Garfunkel disappeared in Grand Central. (Mukasey was one of Greenberg’s textbook and test readers.) And his third college roommate, Jerry Speyer, a successful commercial real estate magnate.

Dr. William Brody, the former Johns Hopkins president who shared Greenberg’s story in a speech at the university’s 2005 graduation, is another founding member, as is McDonnell. In memoriam, so is the late David Rockefeller, once the richest man in the world, who financed the White House fellows program, and became Greenberg’s lifelong mentor.

During a Charlie Rose interview in 2014, Greenberg sat alongside Nobel laureate Dr. Eric Kandel and notable leading researchers in the world of ophthalmology and said the prize that he and his wife were offering was now $3 million.

The experts chatted, among other things, about retinal chip technology that, in its first edition, can allow the blind to see black shadows against a white background. They talked about using stem cells to regrow cells in the retina, the part of the eye that absorbs light and sends it through the optic nerve to the back of the brain, which creates the images we see.

“when i came out of the subway, i had a different worldview—no more doubt and fear.”

“I think about Sandy’s story and wonder, ‘Is anything impossible?’” McDonnell says. “Or, ‘Is everything possible?’”

Indeed, Johns Hopkins researchers and scientists are among those doing work previously only imagined in science fiction. In 2014, Dr. Maria Valeria Canto-Soler induced human stem cells to grow into a light-sensitive, three-dimensional retina that lived in a petri dish. It looked like a jellyfish in water. In April, Dr. Jeff Mumm published findings on accelerating the regeneration of the eyes of zebrafish, which are similar to humans at the cellular level.

While certainly not imminent, the dream is closer to reality than it was in 1984, when Greenberg first seriously considered the idea of regenerating optic nerves and subsequently in 2005, when he proposed it—and more—to Dr. Elias Zerhouni, then director of the National Institutes of Health.

“The eye is just an extension of the brain,” Greenberg says. “The effort to end blindness by 2020 will ultimately, by 2030, be a major assist to regenerating the entire human central nervous system,” meaning research could lead to cures for Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and spinal cord injuries.

This is how things happen: desire. It’s what Salk had. And Garfunkel, who accepted $400 from a then-poor Greenberg—he was a nearly broke student living with Sue at Oxford at the time—so that he could enter into a musical partnership with Paul Simon and create the album The Sound of Silence.

“I tried to help him across those deeply troubled waters,” Garfunkel said in a promotional video for the prize. “He knows all too well how blind people may dream in vivid color, but then awake to the bitter reality of darkness. His vow was to find a way to end blindness for everyone after him who might suffer the same blow.”

And that’s what has been motivating Greenberg since the light turned dark all those years ago.

“My view is we have no choice as a civilization, as a society, except to end it,” Greenberg says. “If you give one blind kid hope, just one, you never know.” More than anything, a world that everyone can see is what he imagines in his mind’s eye.