“Milwaukee?” Baltimore Bullets coach Gene Shue said, moments after his team had finished off one of the greatest upsets in NBA playoff history, unseating a legendary New York Knicks squad team that featured four Hall of Famers in its starting lineup and Hall of Fame coach Red Holtzman patrolling its sidelines. “I’m not even thinking about the Bucks. I’m too happy!”

A reporter whose name has been lost to history had queried Shue—a Baltimore native and former Bullet himself—about how his team was going to fare against the likes of Lew Alcindor and Oscar Robertson in the upcoming 1971 NBA Finals. Shue could have devolved into coach-speak, a language already firm in its conventions five decades ago. He could have prognosticated and analyzed, playing up the opponent that would soon overmatch his club in four consecutive contests.

Instead, he remained in the moment. Pleased with what he and the 13 men he coached had accomplished. Pleased in a way that goes against every never-be-satisfied self-help sports guru that preaches ceaselessly the Phil Jackson-Michael Jordan gospel to today’s young athletes. Shue demonstrated a genuine sense of appreciation. A sense of satisfaction. He took rightful satisfaction in what his underdog team had just accomplished. The previous edition of this New York Knicks team was regarded by contemporaries as one of the greatest in the history of the sport. The reputation of those 1969-1970 Knicks grows by the year, as a cottage industry of books and documentaries about that club have vaulted the championship season of Willis Reed, Walt Frazier, Bill Bradley, and Dave DeBusschere into one of the most thoroughly documented sporting events ever.

No, Gene Shue, the pride of Towson Catholic and the University of Maryland, was not going to look ahead to the Finals. The former point guard had just won the biggest basketball game in the history of his hometown. His Baltimore, of the championship Colts and Orioles, was suddenly a Bullets town. “We deserved it this time,” Shue said, surrounded by a battery of sportswriters, referring to the playoff defeats to the Knicks each of the previous two seasons. “We had so many guys playing hurt who were just tremendous out there.”

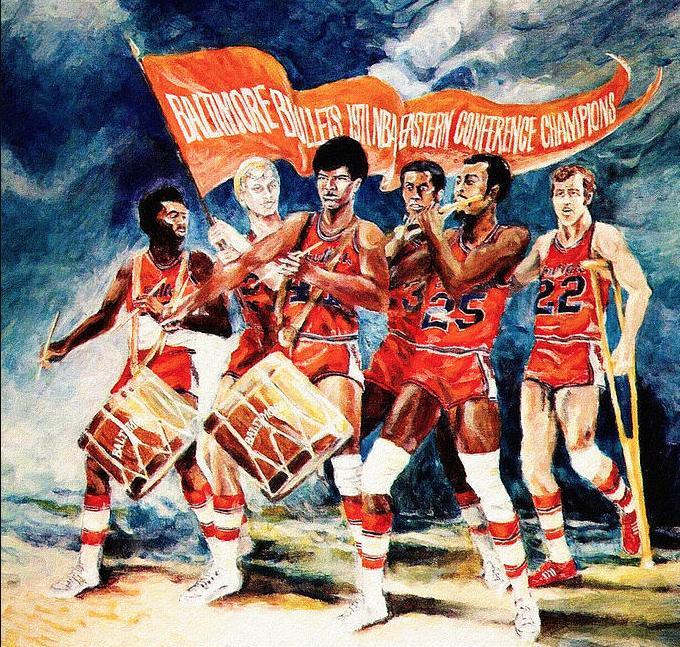

For a few weeks in the spring of 1971, Baltimore’s center of gravity shifted from Memorial Stadium on 33rd Street to the intersection of Howard and Baltimore Streets, the site of the Baltimore Civic Center (now Royal Farms Arena). Fifty NBA playoff seasons ago, the Baltimore Bullets made a startling run to the NBA Finals, upstaging the perennially world class Colts and Orioles, ever so briefly. The Bullets went into the belly of the beast, Madison Square Garden, and came away with a Game 7 win in the Eastern Conference Finals against the defending world champion New York Knicks. The Bullets’ victory in that 93-91 slugfest turned the tables on several seasons’ worth of local anguish caused by New York’s teams. In 1969, the denizens of Memorial Stadium, the Colts and the O’s, suffered historic upsets at the hands of the Jets and Mets respectively. In both instances, upstart New York clubs knocked off Baltimore teams to win world championships, tarnishing remarkable campaigns by the Colts and Orioles that were among the finest in the history of their respective sports.

In 1970, the Bullets themselves had been victims of the same New York team they bested in ’71. The Bullets had posted their second consecutive 50-win season in 1969-1970. Shue had transformed the previously mediocre Bullets into a running-and-gunning, crashing-the-boards kind of outfit—more power and speed than flair and finesse. Once again, Shue’s rough-and-tumble team came up short in the playoffs. In the 1970 series against the Knicks, the Bullets won all three games at the Baltimore Civic Center but lost all four contests at “the world’s most famous arena.”

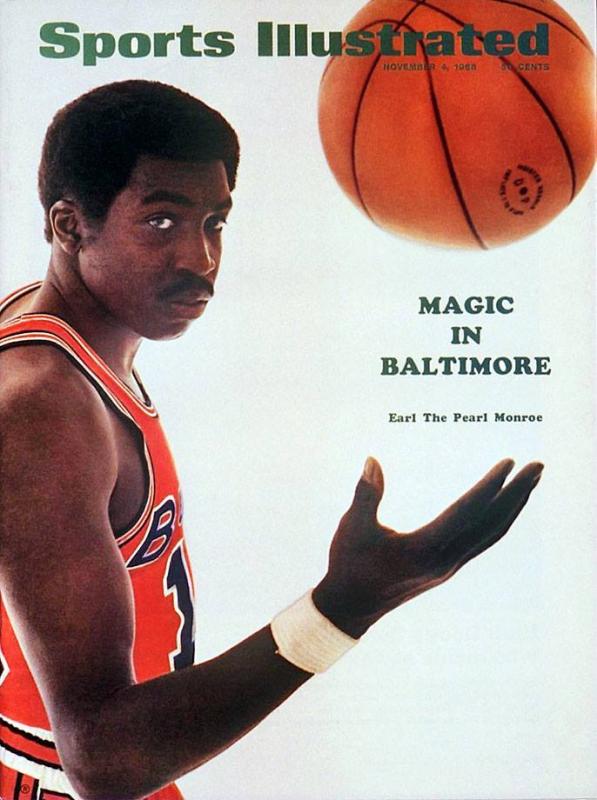

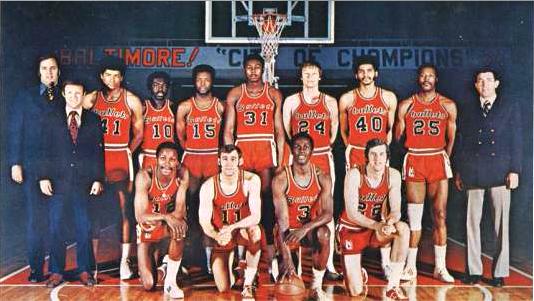

The 1971 season would not have been the year that Baltimore sports fans expected the Bullets to make a postseason run. The Bullets had won the Central Division in a reconfigured NBA, but plodded to a 42-40 regular season record, significantly worse than their 57-win campaign in 1968-1969 and their 50-win campaign in 1969-1970. Then in their eighth season in Baltimore, the Bullets had only managed to win a division title in ’71 because they had been placed in what was easily the weakest of the league’s four new divisions. Nevertheless, the parts were still in place from the two previous seasons—all world leaper and defender Gus Johnson, the team’s power forward; Earl “The Pearl” Monroe, the skillful scoring machine and showman who starred in Baltimore’s backcourt; and 6’7 center Wes Unseld, whose power, grit, and on-court savvy enabled him to dominate much larger men in the low post. Supporting the Big 3 in Baltimore’s lineup were Kevin Loughery, Monroe’s backcourt mate and an elite scorer in his own right, as well as Jack Marin, a southpaw small forward who added plenty of offensive firepower from the wing.

In spite of this strong lineup, the Bullets struggled in 1970-1971. No longer was this team able to sneak up on its opponents. Baltimore’s starting five were all well-known commodities across the league. More importantly, the injury bug stung them all season—Wes Unseld and Gus Johnson both missed significant amounts of time due to injuries. By the time the playoffs rolled around, the Bullets were no healthier—Gus Johnson, in particular, missed much of the postseason with a knee injury. But this club was battle-tested by the spring of 1971 and ready to go toe-to-toe with the best clubs in the East.

Baltimore looked impressive in their opening round series, catapulting to a 3-1 series lead against the Philadelphia 76ers. Wes Unseld outmuscled Philadelphia’s frontcourt in the series’ early games while Loughery, Monroe, and Marin took turns leading the team’s offense attack. By Game 5, the city of Baltimore had caught on. More than 12,000 fans filled the Baltimore Civic Center and created a raucous atmosphere. Typically, the Bullets had drawn middle-of-the-pack numbers for much of their tenure in the city, averaging just over 6,000 fans per game during the 1970-1971 season. Despite the energy in the building, Billy Cunningham poured in 32 points for the 76ers, who withstood a furious Bullets comeback to win 104-103. Cunningham once again prevailed in Game 6, posting a game-high 33 points in another 76ers win. In Game 7, the Bullets rose to the occasion, seemingly drawing energy from the boisterous home crowd as they battered Philadelphia on the boards and finished off the 76ers.

On the eve of the Eastern Conference Finals, the basketball cognoscenti gave Baltimore little chance of unseating the world champion Knicks. New York had won yet another division championship that season and hammered the Atlanta Hawks in the opening round. Initially, the series went according to plan as New York, playing before nearly 20,000 partisans stacked up to the MSG’s ceiling, outlasted the Bullets in Game 1 and pummeled them in Game 2. A twisted knee had kept Gus Johnson out of these games, as it did the first five contests in the series, and much of the rest of the Bullets’ team seemed beaten up and frazzled after the losses.

New York looked primed for a sweep until the rowdies in Baltimore, who filled the Civic Center to the rafters and made just as much a ruckus as their counterparts in Manhattan, hailed a Wes Unseld-led Bullets team to decisive victories in Games 3 and 4. In Game 3, Unseld snagged 26 boards, dished out 9 assists, and scored 18 points. In Game 4, John Tresvant, playing in place of Johnson, grabbed 17 rebounds while Unseld pulled down 16, giving the Bullets a 55-39 rebounding edge over New York in a 101-80 rout. After the ambush in Baltimore, New York played a slower, more deliberate style in Game 5 and won by an 89-84 margin, pushing Baltimore to the brink of elimination.

Once again, Baltimore rose to the occasion in front of its home crowd, routing New York 113-96 with the return of Gus Johnson to the lineup. Once again, Baltimore and New York would play a Game 7 at Madison Square Garden. Once again, each club had won the three contests in their own buildings. But this time, it wouldn’t be another case of the Bullets giving it the old college try against a team destined for bigger things. The Baltimore Bullets brought an end to talk of a New York Knicks dynasty on a Monday night at Madison Square Garden. Initially, the game went according to the Knicks’ game plan. It was a plodding and methodical half-court contest. Yet Baltimore hung around and remained down just three at halftime. The Bullets came out in the third period and started raining down shots on the Knicks. Baltimore led 73-68 entering the fourth quarter and held tight to that lead. Earl Monroe led the way for Baltimore, as he usually did, with 26 points. Unseld swatted away a Bill Bradley shot with three seconds remaining, preserving Baltimore’s 93-91 advantage as time expired.

Head coach Gene Shue’s exuberance in the aftermath of the Bullets’ victory was reflective of a grander catharsis the win brought to his hometown. The win got the collective monkey not only off his team’s back but, more broadly, it gave Baltimore’s sports fans a taste of revenge against the Big Apple, whose teams had devastated their beloved football and baseball teams in recent years.

This love affair between the Bullets and Baltimore proved far too short lived, of course. The ’71 NBA Finals were over in a flash as Alcindor (who adopted the name Kareem Abdul-Jabbar shortly after the series ended) and Robertson’s Bucks battered Baltimore for four straight games, none of which were particularly competitive. And then just three games into the 1971-1972 season, Baltimore traded Earl “The Pearl,” who had been locked in a contract dispute with team management, to the hated Knicks for a couple of players and some cash. Gene Shue’s teams never again reached the Eastern Conference Finals and he was fired after the 1972-1973 season. The Bullets were themselves not long for Baltimore at that point. In the fall of 1973, owner Abe Pollin, a Washington, D.C. native, moved the Bullets to a new arena in Landover and rechristened them the Capital Bullets before changing their moniker to the Washington Bullets the following season. Unseld, an icon in Baltimore who passed away last year, finally got a championship with Washington Bullets in ’78. Meanwhile, Baltimore has yet to make a return to the NBA, despite the game’s evident popularity at all levels of play in the area. Nevertheless, for a few short weeks in the spring of ’71, Baltimore was, in fact, a great NBA city and it was a Bullets town.

Clayton Trutor holds a PhD in US History from Boston College and teaches at Norwich University in Northfield, Vermont. He is the author of Loserville: How Professional Sports Remade Atlanta—and How Atlanta Remade Professional Sports (University of Nebraska Press, 2021). He’d love to hear from you on Twitter: @ClaytonTrutor