Sports

A Man for All Seasons

Babe Ruth, the once “hopeless incorrigible” kid from Baltimore, made baseball, and America, bigger and better.

Baltimore outfielder Johnny Honig practically sat on the right-field fence at Oriole Park each time the Boston Red Sox’s Babe Ruth came to the plate, according to contemporary accounts. He might as well have been positioned in the front yards along Greenmount Avenue for all the good it did over the two-game exhibition series between the International League O’s and defending champion Red Sox. Just months before, with a display of World Series pitching as great as the game had ever seen, Ruth led Boston to their third title in four years, and his homecoming to Baltimore was trumpeted across the city. Not only had he established himself as baseball’s top left-handed pitcher, the rags-to-riches southpaw had begun playing the outfield between starts and socked 11 home runs the previous season, tying for the most in the Major Leagues.

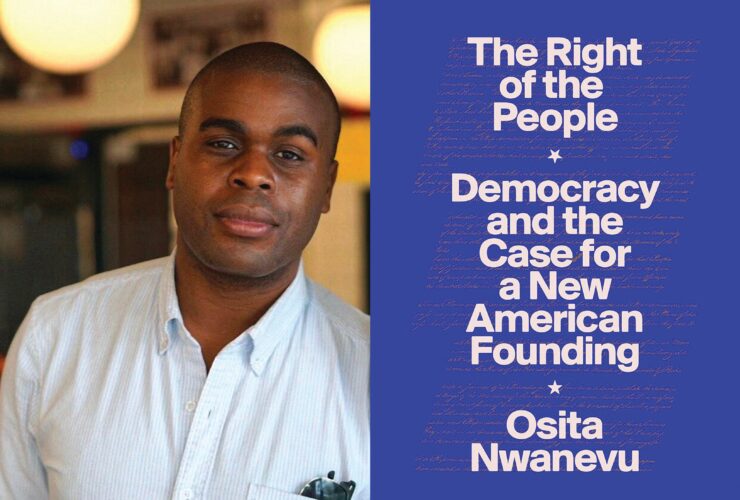

Depiction of early Baseball card of ruth as a pitcher with the Boston red sox.

After walking in his first at bat on the Friday afternoon of April 18, 1919, the 6-foot-2-inch Ruth blasted a white rocket in his second plate appearance—said to have cleared both Greenmount Avenue and a telegraph wire across the street—pleasing the huge Baltimore crowd, which had turned out to catch a glimpse of the local hero and suddenly budding slugger. He repeated the feat with another home run on his next turn. On his third at bat, still swinging from his heels, Ruth unloaded what witnesses believed was the longest home run ever seen at the Waverly ball yard. In the ninth inning, he smashed a fourth dinger for good measure. Later, the Baltimore News American ran a photo graphic illustrating where Ruth’s bombs, three of which traveled more than 500 feet, departed from home plate and returned to Earth in the neighborhood behind the ballpark. “Babe did it so easily that the fence actually appeared to be just about where second base usually is found,” The Baltimore Sun reported. “It must be nice to live in the 2000 block of Greenmount Avenue these days,” The Sun added, “for the kiddies will have all the baseballs they need for the season after the Red Sox leave.” The paper was right.

The following afternoon, Ruth started the game on the mound, and when he came to bat, Honig was back on his perch in right field, once again, to no avail: Ruth rocketed two more roundtrippers in his first two plate appearances—making it six home runs in six consecutive bats—the deepest of which on Saturday landed on a rowhouse rooftop.

The half-dozen consecutive blows were heralded in the national press as “a baseball record.” They pushed Ruth’s exhibition home run total that spring to 18 when the single-season American League record stood at 16. More than anything, Ruth’s binge in Baltimore presaged a 29-home run eruption during the ensuing 1919 season. It was an individual performance completely out of proportion in baseball history: Ruth’s personal home run total eclipsed that of 11 of the 16 Major League teams.

During that momentous 1919 campaign, Ruth led baseball not just in home runs, but runs batted in, runs scored, on-base percentage, slugging average, and total bases, while still going 9-5 in 15 starts and posting a sterling 2.97 ERA for the Red Sox. And then, the day after Christmas, exactly 100 years ago this month, Boston owner Harry Frazee sold his superstar to the New York Yankees—a gift, it would turn out, at $100,000—in order to invest in a Broadway play named My Lady Friends (later adapted into the musical No No, Nanette). Baseball, and the country, would never be the same.

“Fans [drove] miles in open wagons through the prairies of Oklahoma to see him in exhibition games,” Yankee teammate and Hall of Famer Waite Hoyt recalled after Ruth died of cancer in 1948. “I’ve seen them—kids, men, women, worshippers all—hoping to get his name on a torn, dirty piece of paper, or hoping for a grunt of recognition when they said, ‘Hi-ya, Babe.’

“He never let them down, not once.”

The kid who had spent 12 years at St. Mary’s Industrial School for Boys—who had been officially labeled a “hopeless incorrigible,” after he was sent away at 7 for drinking, stealing, chewing tobacco, and refusing to attend school—would make the national pastime, and America, bigger and better.

George Herman Ruth Jr. was a few days past his 19th birthday when Baltimore Orioles owner and manager Jack Dunn visited St. Mary’s, the Catholic-run institution for orphaned and delinquent children on Wilkens Avenue, seeking permission to sign their talented pitcher to a $600-a-year contract. Legally, because Ruth was not yet 21, he was paroled into the guardianship of Dunn, who knew the school’s superintendent. By mid-summer, Ruth was already showing promise, and the Red Sox purchased his minor league contract from Dunn and the Orioles. Five years later, he was—all at once it seemed—the game’s best, and far and away most colorful, player. In an era before professional football or basketball had gained popularity, when radio, newsreels, and daily newspapers dominated pop culture, it was Ruth who became America’s first rock star. He was the first athlete to hire an agent and the first to endorse commercial products and first to have a candy bar named after him. He visited barrooms, sick kids in hospitals, whorehouses, hot dog stands, and orphanages with equal enthusiasm (his famous carousing settled down after his second marriage). He loved mugging for the cameras—in costumes, with animals, but mostly with dirty-faced kids who reminded him of himself—and eventually became the most photographed person on the planet. He is credited with saving baseball in the wake of the 1919 Black Sox scandal when members of the Chicago White Sox had conspired with gamblers to throw the World Series. Children everywhere adored him.

“fans [drove] miles in open wagons through the prairies of oklahoma to see him play. he never let them down, not once.”

“I saw it all happen, from beginning to end,” Harry Hooper, a Boston Red Sox teammate of Ruth’s, recalled at his own induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1971. “But sometimes, I still can’t believe what I saw: This 19-year-old kid, crude, poorly educated, only lightly brushed by the social veneer we call civilization, gradually transformed into the idol of American youth and the symbol of baseball the world over—a man loved by more people and with an intensity of feeling that perhaps has never been equaled before or since.

“I saw a man transformed into something pretty close to a god,” Hooper continued. “If somebody had predicted that back on the Boston Red Sox in 1914, he would’ve been thrown into a lunatic asylum.”

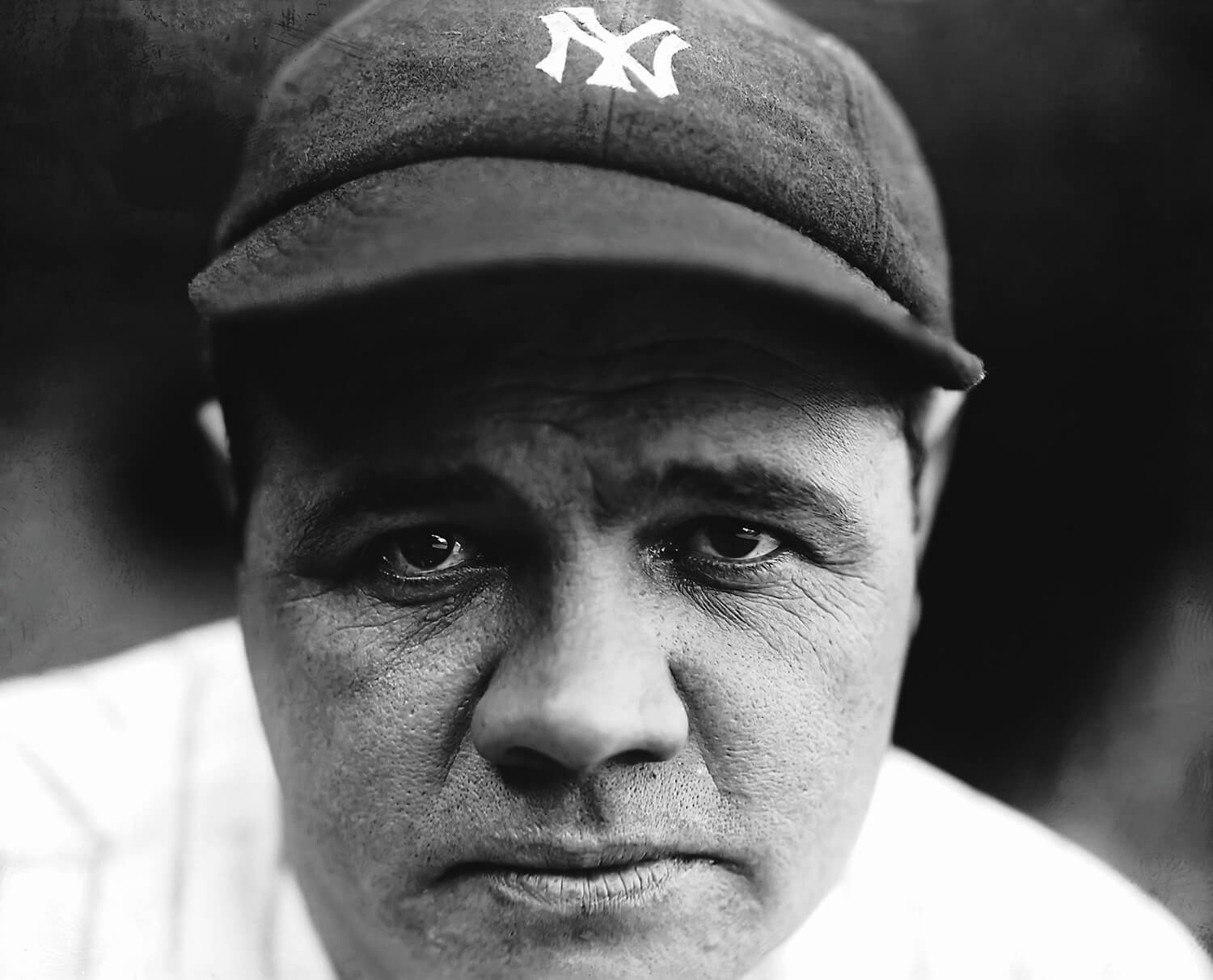

Portrait of the future Hall of Famer in 1927.

That Ruth changed the course of baseball history is so well documented that it hardly needs mention. He took what previously had been a small-ball game of singles and sacrifice bunts and turned it on its head with his haymakers. But he was also changing the baseball landscape around him. Prior to his arrival, New York’s other two teams, the Giants and Dodgers, each outdrew the Yankees, who were considered a second-rung club. Ruth single-handedly turned the tables when he arrived in the Big Apple in 1920 and subsequently smashed 54 home runs. The Yankees became the biggest sensation in baseball that summer and the first team to draw more than 1 million fans in a year. But during Ruth’s first two seasons in New York, the Yankees still borrowed the Giants’ stadium for home games. The Italian immigrant fans in the Polo Ground bleachers, not surprisingly, took to the fun-loving Ruth and quickly adopted him as one of their own, Bambino. It was the perfect, affectionate translation of Babe, playing off both Ruth’s childlike nature and bruising bat. Headliner writers often cut it to “Bam”—and it stuck. (The Red Sox, who had won five of the first 15 World Series, as New England fans and baseball aficionados well know, would fare worse than the Giants and Dodgers in Ruth’s wake. Suffering under “The Curse of the Bambino” for selling the greatest ballplayer who ever lived for mere greenbacks, Boston would not win a title for the remainder of the 20th century.)

“a man loved by more people and with an intensity of feeling that perhaps has never been equaled before or since.”

By the 1922 season, the Yankees had completed their then-unheard of 75,000-seat cathedral—henceforth known as The House that Ruth Built after he christened the new stadium with a home run on Opening Day. By 1923, at the age of 26, Ruth had reset the Major League Baseball record for career home runs. In 1927, when he hit a titanic 60 home runs—his season-long pursuit to break his previous record of 59 had taken on the fever of a one-man traveling circus—his total again topped every other American League club. In September alone that year, he hit more home runs (14) than the entire Cleveland Indians starting lineup did all season.

“Ruthian” entered the Oxford Dictionary as a synonym for colossal and baseball attendance took off across the country. In his on- and off-the-field ethos, Ruth personified the Roaring ’20s. “I swing big, with everything I’ve got,” he said. “I hit big, or I miss big. I like to live as big as I can.”

Ruth eventually would lead the Yankees—with a lineup of guys named Gehrig, Lazzeri, Combs, Meusel, and Koenig (aka Murderers’ Row)—to the first four of their 27 and counting World Series titles. By the late 1950s, both the Giants and Dodgers had thrown in the towel, ceding New York to the Yankees and fleeing to the greener pastures of California.

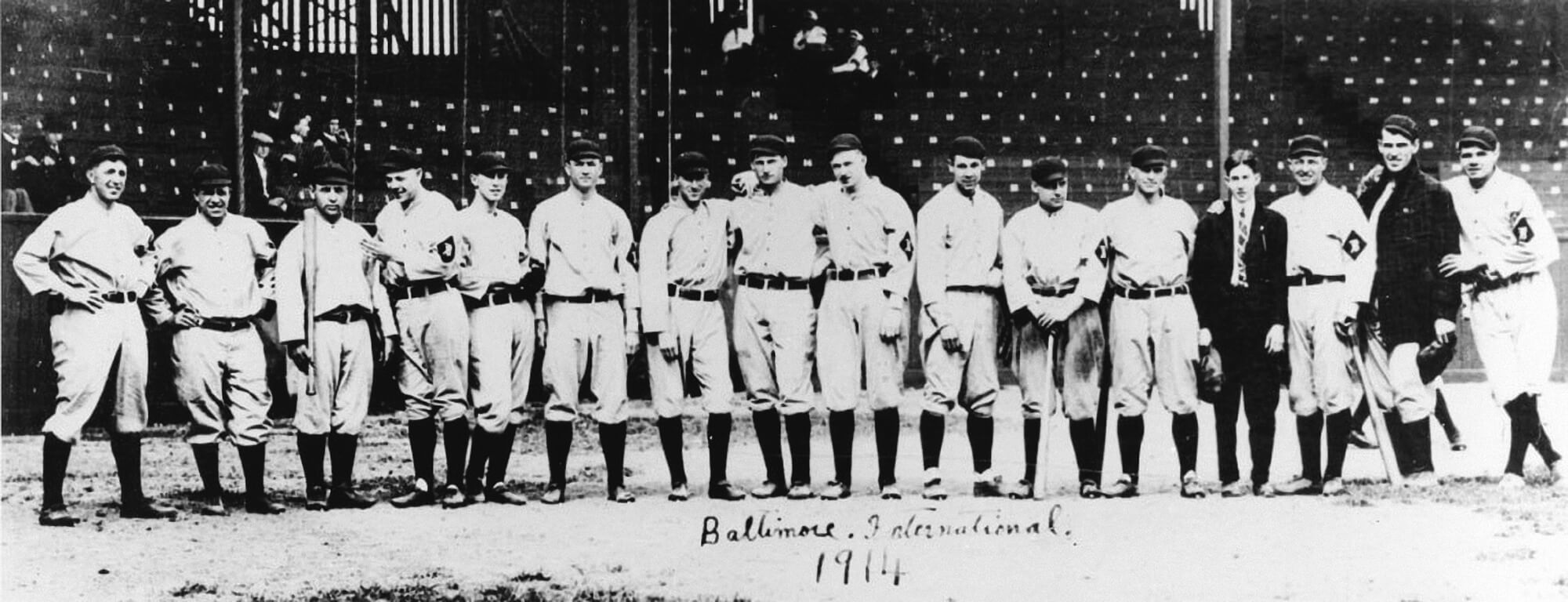

Ruth, on the far right, as a rookie pitcher with the International League Baltimore Orioles.

Lost, however, in the Bunyanesque shadow of his baseball records are other facts of Ruth’s life. Facts that reveal Ruth’s broader legacy as a humanitarian beyond his well-known and frequent visits to children’s hospitals and orphanages. Those facts are worth remembering, too.

At the height of his celebrity, Ruth played an exhibition game inside New York’s Sing Sing, the state’s maximum-security institution, against a prison team, signing autographs and joking with the 1,500 inmates in attendance from start to finish. He pitched and, naturally, hit three home runs, including a couple before the game over the prison wall. Also forgotten is the fact that during an exhibition in Hawaii, Ruth visited a leper colony for a day despite warnings that he could contract the disease. If they could not come and watch him play, Ruth said, he would go to them.

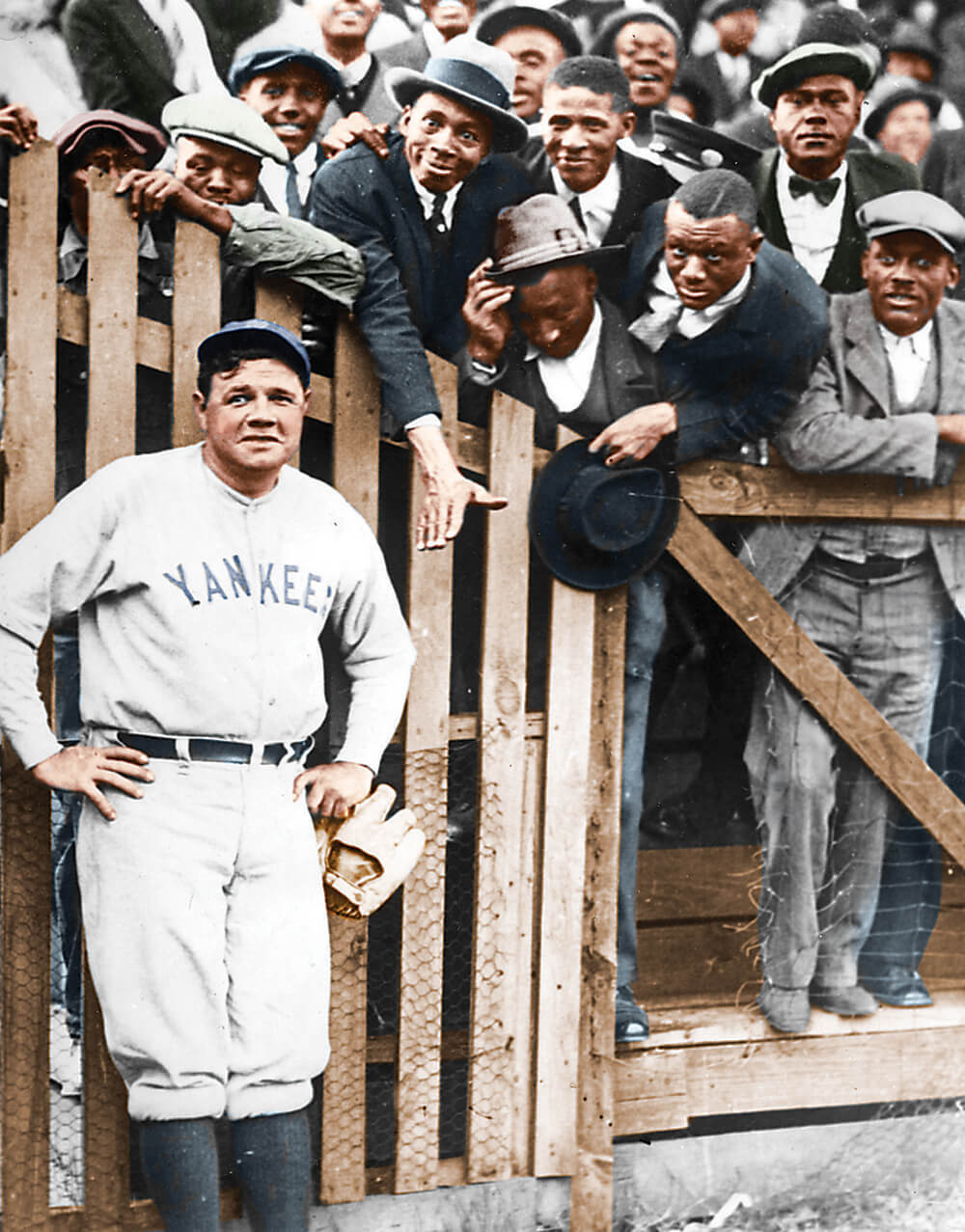

A favorite among all baseball fans, Ruth regularly participated in barnstorming games against negro League and cuban all-star teams.

In the midst of Jim Crow bigotry and repression and baseball’s color line, from his earliest days as a professional, Ruth competed against Negro League and Cuban All-Star clubs during off-season barnstorming tours—leaving no doubt where he stood on the issue of taking the field with black ballplayers. The influential black newspaper the Chicago Defender declared Ruth “a friend of the race.” At a time of police-enforced segregation, lynching, and rampant KKK activity, not just from the Deep South but across the country, the most famous person in the nation—a born-poor white kid from Baltimore—publicly implored white fans to go watch Negro League games if they wanted to see some good baseball. When his epic 1920 season ended, Ruth received hundreds of barnstorming invitations and could have played anywhere in the country—or nowhere at all, for that matter. Instead, of the approximately 15 games that he picked, five were against Negro League teams. Afterward, Ruth set sail for Cuba, where he joined legendary manager John McCraw and his Giants to play another series of contests against a combination of Latino and black ballplayers. Symbolically, his actions spoke volumes. If Ruth, not just a baseball figure, but a cultural icon, didn’t hestitate to join black ballplayers on the diamond, why did the color line remain in place?

Ruth paid a price for it, too, including a suspension related to his overall barnstorming activities, but he never stopped playing and making friends among black ballplayers. Some have suggested, including his daughter, that his integrated barnstorming tours may have cost him a shot at managing after his playing career because owners feared he would push publicly to end baseball’s so-called “gentleman’s agreement” that kept black players out. Negro League Hall of Famer Judy Johnson told Ruth biographer Bill Jenkinson that the white ballplayers they encountered generally fell in to three categories. The first group refused to take the field against black players under any circumstances. Next, there were the guys who didn’t like African Americans, but agreed to play in order to make a buck. The third and smallest group, Johnson said, enjoyed the camaraderie. This was the camp Ruth belonged to, along with Dizzy Dean and a few others. “He was quite a guy, always a lot of fun. All the guys really liked him,” Johnson said of Ruth. On the other hand, he added, “We could never seem to get him out no matter what we did.”

Familiar with Harlem’s Cotton Club, Ruth was also the first person to invite a black man, entertainer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, into the Yankee clubhouse. More than mere acquaintance, Robinson served as an honorary pallbearer at Ruth’s funeral.

“he was quite a guy, always a lot of fun,” Negro League star judy johnson said of ruth. “All the guys really like him.”

“Ruth never met someone he considered a stranger,” Jenkinson says. “It’s not that he was colorblind or didn’t see someone’s color. It just made no difference to him.”

And during a period when the United States was implementing racist and xenophobic immigration laws, Ruth joyfully traveled to Mexico, Cuba, and the Philippines as an ambassador for the game and the country. He visited Hawaii (then a foreign country), China, and Japan, where he was feted like no other American before or since. (When charging Japanese fighters later shouted, “To hell with Babe Ruth!” at American soldiers during World War II, there could be no bigger insult.)

After Ruth had retired, when the Nazis’ “Final Solution” was at its terrifying height in December 1942, 50 prominent German-Americans signed a full-page advertisement in The New York Times and nine other daily newspapers “in denunciation of the Hitler policy of cold-blooded extermination of the Jews of Europe.” By far, the most recognizable name to Americans: George Herman “Babe” Ruth.

Ruth supported women’s sports, too. On one occasion, he and Gehrig faced a top women’s hardball pitcher—both striking out for the cameras . But the most humanitarian thing Babe Ruth ever did, he did every day. The son of a badly alcoholic mother and uninterested father, Ruth not once denied or forgot the poverty and circumstances into which he was born. Or the Xaverian Brothers, who taught him reading, writing, and their religious values at St. Mary’s. In particular, he credited Brother Matthias, a 6-foot-6 father figure who taught him baseball, with saving him from the penitentiary or cemetery. Ruth shared his story with every newspaperman who came his way for an interview and implored adults to never give up on any child.

During one barnstorming trip to Kansas City in 1927, author Jane Leavy recalls in her recent biography, The Big Fella , Ruth and Lou Gehrig visited three orphanages, two white and one black, and the white-only Mercy Hospital before a parade at noon and an afternoon game.

Somewhere in their schedule, Leavy dug up in her research, representatives from the town’s black hospital, Wheatley-Provident Hospital, invited Ruth and Gehrig to stop by. Ruth skipped lunch that day at the Kansas City Athletic Club to visit sick children. A photograph of the massive Ruth cradling an emaciated infant circulated among the nation’s most prominent African-American newspapers.

After his father’s death outside the Eutaw Street saloon that Ruth had bought him as a young pro (his mother had died when he was 15), the slugger no longer spent much off-season time in Baltimore—other than to visit St. Mary’s, which he did whenever the Yankees were down the road playing the Washington Senators. As much as he surely hated being locked inside its gates for most of his youth, it was his childhood home. When St. Mary’s was struck by a devastating fire, Ruth not only cut a large check, he brought the entire 49-member all-boys school band with him and the Yankees on their final road trip of the season so they could play in front of big-league crowds and collect donations.

“When Babe Ruth was 23, the whole world loved him,” his second wife, Claire Merritt Ruth, said in her memoir. “When he was 13, only Brother Matthias loved him.”

BABE RUTH IN BALTIMORE

Catching up with Ruth beyond the not-to-be-missed Babe ruth birthplace museum

- 1. George Herman Ruth Sr.’s Gravesite Ruth’s father died in 1918 when Babe was still with the Red Sox. He is buried at Loudon Park Cemetery. 3801 Frederick Ave.

- 2. Babe Ruth Field Former site of St. Mary’s Industrial School for Boys, now on property managed by The Y of Central Maryland. 3225 Wilkens Ave.

- 3. Ruth's Early Childhood Home From 1897-1901, the Ruth family's 12-foot-wide brick rowhouse where he lived as a young boy when his father worked as a lightning rod salesman. 339 S. Woodyear St.

- 4. Babe Ruth Birthplace Museum First home of the Baltimore legend (Feb. 6, 1895). Not to be missed by baseball fans. 216 Emory St.

- 5. Babe Ruth Statue Babe’s Dream at Oriole Park at Camden Yards. Ruth’s father once ran a saloon that was located behind second base. 33 W. Camden St.

- 6. The Goddess Gentleman’s Club Formerly Ruth’s Café, another bar run by Babe’s father. 38 S. Eutaw St.

- 7. St. Paul Catholic Church After his first year with the Boston Red Sox, Ruth married his first wife here on Oct. 17, 1914. 3755 St. Paul St., Ellicott City.

- 8. Peabody Heights Brewery Former home of Oriole Park. 401 E. 30th St.

Ruth had arrived at his first spring training camp in Fayetteville, North Carolina, en route to Florida, just weeks after Jack Dunn, the Orioles’ legendary local baseball man, had signed him out of St. Mary’s. His naive excitement over the most ordinary things—trains, elevators, hotels, restaurants, menus, a few dollars in his pocket—led someone to refer to Ruth as “a babe in the woods.” He’d already been tagged “Jack Dunn’s baby” by other players and newspapermen. By March 7, 1914, when he hit his first professional home run in the last inning of an exhibition game at the Cape Fear Fair Ground, his name had already been combined and shortened to “Babe Ruth” in the sports pages. A historical marker remains at the spot where the preternaturally powerful teenager cracked the memorable 405-foot shot. “I hit it as I hit all the others,” he said later, “by taking a good gander at the pitch as it came up to the plate, twisting my body into a backswing and then hitting it as hard I as I could swing.”

According to Washington Post sportswriter Shirley Povich, the most striking thing about a Ruth at bat was not simply the power that he generated, but also the beauty of his swing. “There was no violence in the stroke,” Povich told Sports Illustrated before his death in 1998. “He put everything into it, but he never looked like he was extending himself. By the time he hit the ball, he had taken a long stride forward and had turned his shoulders and ass and wrists into it, swinging through it. Exquisite timing.

“I can close my eyes and not only still see the swing, but still admire it.”

“when Babe ruth was 23, the whole world loved him,” HIs second wife, Claire Merritt ruth, said. “when he was 13, only brother matthias did.”

Myths, of course, grew around Ruth, whose games were not televised and dissected on SportsCenter. But Ruth really did promise a seriously ill, hospitalized boy named Johnny Sylvester he’d hit a home run in Game 4 of the 1926 World Series. Incredibly, he put it in writing—on an autographed ball he sent to the 11-year-old—today on display at the Babe Ruth Museum at his birthplace on Emory Street. Ruth did not quite keep the promise, however. He hit three home runs. Little Johnny Sylvester would survive, live a long life, and in fact, visit Ruth as an adult when his hero was dying of cancer.

The famous “Called Shot” in the fifth inning of Game 3 of the 1932 World Series? Well, a recovered 16-mm home movie of the game definitively shows Ruth gesturing vigorously and pointing toward the Chicago Cubs bench and pitcher Charlie Root (and possibly centerfield) before the dramatic blow—his second of the game and said to be the longest ball ever hit into the Wrigley bleachers. The Called Shot was named such in at least one major paper the next day by a sportswriter who was on hand. Lou Gehrig, who was in the on-deck circle, was sure Ruth had called his shot. “What do you think of the nerve of that big monkey, calling his shot and getting away with it?” Gehrig asked a reporter the following day.

Future Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens, who attended the game, always maintained Ruth had done it. Much of the notorious animosity between Ruth and the Cubs had been started by Ruth, who wasn’t above trash talking from time to time. He had called the Cubs’ players “cheapskates” for short-shrifting former Yankee teammate Mark Koenig, whom Chicago picked up during the season, of a full World Series bonus.

For his acclaimed biography about Ruth— Babe: The Legend Comes to Life —Robert Creamer discussed Ruth, the human being, with two players: Ernie Shore, who played with him in Baltimore, Boston, and New York, and Bob Shawkey, who played with and then managed Ruth for a year in New York. Neither, Creamer noted, had any special reason to be fond of Ruth, given his background and wild reputation as a young ballplayer. Quite the opposite, Creamer felt. Shore, for example, had attended college, served in the military, and later became a sheriff in his native North Carolina.

Yet, Shore laughed when Creamer inquired about the real Ruth, whom he’d roomed with in New York (“I was the only guy he’d listen to,” Shore said). “He was the best-hearted fellow who ever lived,” the former pitcher said. “He’d give you the shirt off his back.”

Shawkey had pitched against Ruth and later was his teammate on the Yankees and his manager in 1930, thus becoming Ruth’s boss for a season. Ruth desperately wanted to be made the manger of the Yankees, and there were reports that he resented Shawkey getting the job. Shawkey told Creamer some lively stories about Ruth: about fights on the bench and in the clubhouse with teammates, about the time former Yankees’ manager Miller Huggins fined Ruth $5,000 for general misconduct, and about the wild pennant celebration on the return train home from Boston when Ruth and Bob Meusel, another big Yankee great, banged on Huggins’ compartment and informed the tough, if diminutive, manager they were going to toss him off the train.

Shawkey, a gentleman by all accounts, was the kind of man who might not appreciate a showman and rabble-rouser like Ruth, Creamer thought.

In fact, Creamer felt like he might have even picked up on a vein of anti-Ruth sentiment during the interview. “Why did some people dislike the Babe?” Creamer asked, leadingly. Shawkey gave him a dumbfounded look. “People sometimes got mad at him,” Shawkey said, “but I never heard of anybody who didn’t like Babe Ruth.”