News & Community

This Land Was Their Land

Thousands of Lumbee Indians migrated to Upper Fells Point after World War II. Decades later, members of the tribe are claiming their history.

By Ron Cassie

Photo Below: East Baltimore Church of God, on E. Baltimore St., c. 1960s. Photography Courtesy of Rev. Robert E. Dodson Jr./Colorization by Katie Lively

“People were basically running here to get away from farming,” says Jeanette Walker Jones. The 80-year-old Lumbee tribe member is sitting on her porch, near her flower bed and three flags—American, Maryland, and Lumbee—which are softly waving in the afternoon breeze as she recalls her first impressions of Baltimore. “Any job was better than that. But I didn’t want to move to Baltimore. I was 15 in 1957 and didn’t have a choice. The first time I’d visited, I saw these tall buildings and people eating what I thought were ‘bugs,’ which is what crabs looked like to me. I came from a house with three rooms and no indoor plumbing. I begged my mother to leave me with my grandparents in North Carolina.”

Her sister, brother-in-law, and their four kids, members of the North Carolina-based Lumbee tribe, had migrated to Baltimore several years earlier. Her sister’s husband found employment as a commercial painter and eventually the family moved into a three-bedroom, second-floor apartment in Upper Fells Point. Jones’ father had passed away years before and soon enough her mother, along with Jeanette and her younger sister, moved north as well. Rural, low-income Robeson County offered little work outside share cropping and little in general beyond family, farming, and familiarity. The social structure was built upon a tripartite system of bigotry that divided public life—schools, theaters, buses, restaurant service, swimming pools, bathrooms—into “White,” “Indian,” and “Colored.”

The racism was so ingrained, Jones barely gave it thought growing up. The full realization of the centuries-old apartheid didn’t register until she returned to Robeson County in the mid-1960s with her own daughters. “We were visiting and went into town to a dime store,” recalls Jones, who subsequently taught Indian Education in Baltimore public schools. “In the back of the store, they had a restaurant and a soda fountain. Naturally, one of my girls wanted a drink, but they said they wouldn’t serve her. I asked why, and they said, ‘Because she’s Indian.’ Well, I knew the history there, but since I’d been in Baltimore for a few years, I’d kind of forgotten about it. My girls were so young that they didn’t understand what was happening, but I certainly did.”

So many Lumbee Indians would make their Great Migration-adjacent journey to the city during its post-World War II industrial boom, they affectionately nicknamed the area where they settled “the Reservation.” Fitting into a Black and white segregated city proved a whole new challenge, however. While not as overt as in North Carolina, prejudice remained an issue. Southeast Baltimore police began referring to the Lumbee newcomers as “Lombardees”— after the busy street that cut through their neighborhood—and themselves as “Indian fighters.” Established residents, many working-class Polish, Italian, Greek, and Jewish immigrants and their descendants, did not know quite what to make of the latest arriving group, who did not look or dress like the Indians in the popular Westerns of the period. The segregated city’s Black residents were equally nonplussed.

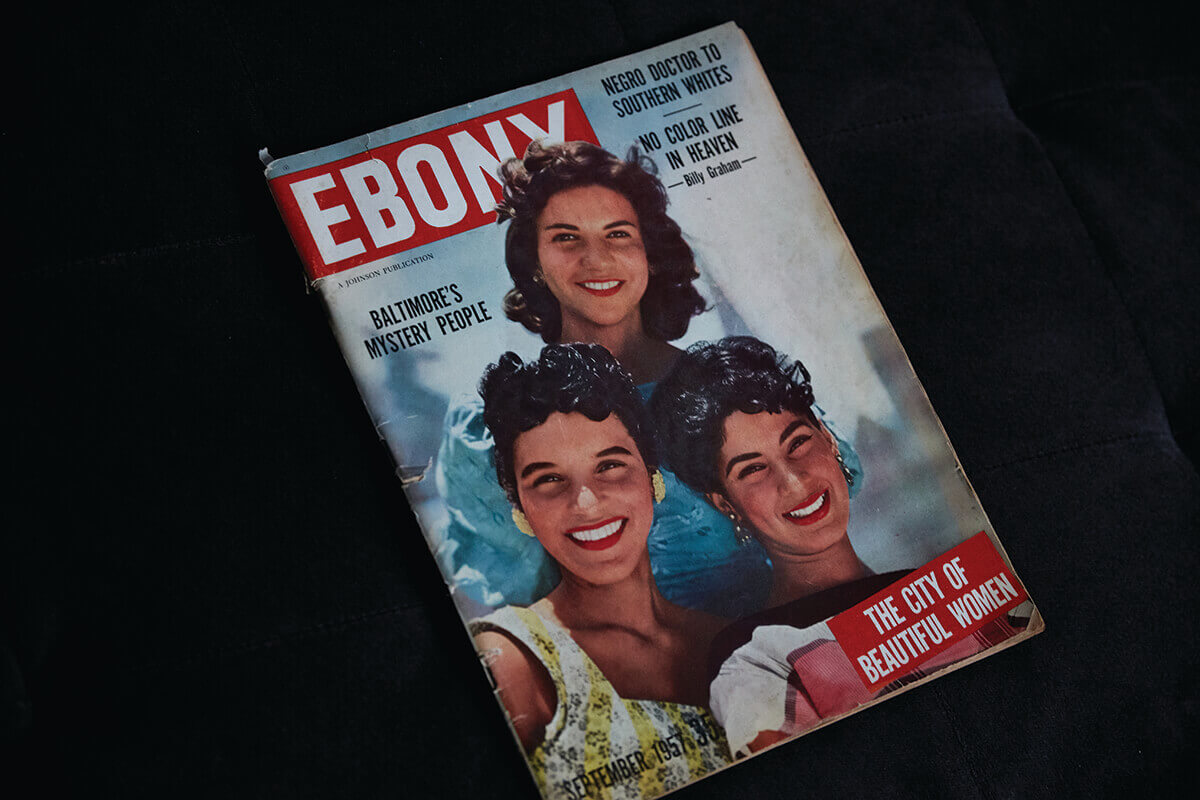

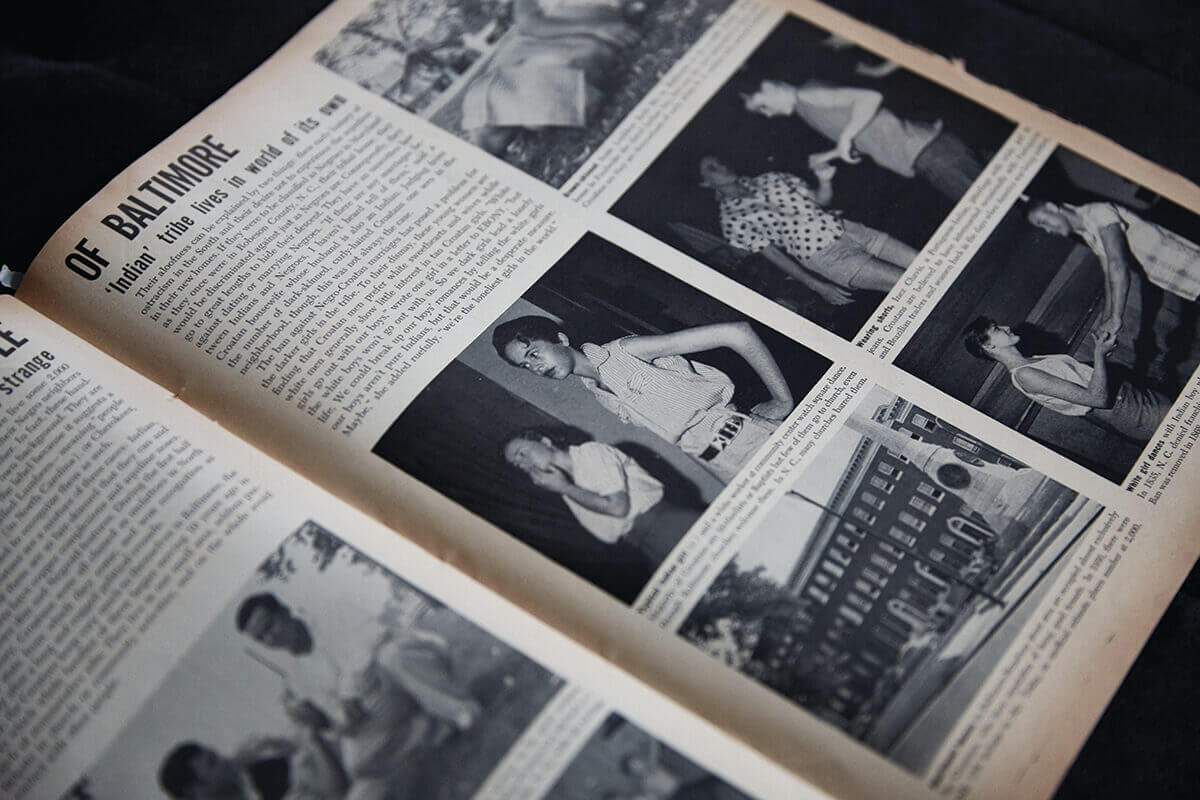

To many in Baltimore, the close-knit Lumbees were a curiosity, not just because of their assertion of Native American identity, but because they did not match Native American stereotypes of physical appearance, language and accent, religion, foodways, and dress portrayed by Hollywood. In 1957, Ebony magazine sent a reporter and photographer to document Southeast Baltimore’s newly urbanized tribe in a four-page spread. The story and photo essay, which coincidentally included a picture of the teenage Jones at a nearby McKim Center dance, was titled: “Mystery People of Baltimore: Neither red, nor black, nor white. Strange ‘Indian’ tribe lives in world of its own.”

Ashley Minner at the Baltimore American Indian Center; Minner holding a photograph of a Lumbee woman shelling peas at the Baltimore American Indian Center.From top: Photography by Jill Fannon; Photography by Xueying Chang of the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage

T he Lumbees are the largest tribe east of the Mississippi and the ninth largest in the country, with 55,000 members. They take their name from the Lumbee River, which is fed by the woodland swamps of tribal territory in Robeson and the surrounding counties of southeastern North Carolina. The tribe’s complex history and Native American identity has long been a source of stigma—and skepticism—from outsiders, including Baltimoreans, who tend to reduce Indigenous authenticity to genetic features, like straight black hair and high cheek bones, and “pidgin” English. At different times, the Lumbee nation has also been known as or called Croatan, Cheraw, and Cherokee Indians of Robeson County. One theory connects their origin story to the Hatteras Indians of the Outer Banks. Another, since discarded, to the Lost Colony of Roanoke. What is broadly understood is that they descend from an amalgamation of Algonquian, Iroquoian, and Siouan speaking people who settled in the region in the 1700s and 1800s, forming a tribal bond as they sought to escape European disease, colonial wars, forced migration, and enslavement.

By the mid-1950s, several thousand Lumbee had come together in a roughly 64-block area in Baltimore, bordered by South Broadway, Washington Hill, and Butchers Hill to the east and north, and Patterson Park and Fells Point to the west and south. Later estimates would put their booming population between 4,000 and 7,000 by the late 1970s and early 1980s. (The official U.S. Census number, assumed to be an undercount, put 3,500 Native Americans in Baltimore and 8,000 statewide in 1980.) Other Lumbee members, also migrating north for jobs and relief from Jim Crow laws, moved to Detroit, Philadelphia, and other cities. They brought with them a distinctive lilting Southern accent and a strong work ethic, swapping their low-wage farming jobs for employment in auto factories, steel plants, the construction trades, and the restaurant and service industries. Many Lumbee in East Baltimore became entrepreneurs, opening small businesses like Hartman’s BBQ Shop, Revels’ grocery, and Locklear’s grocery—all formerly in the 1700, 1800, and 1900 blocks of East Baltimore Street—plus Pop’s on East Fairmount, which sold hog maws and chitlins, and George’s Grocery & Grill, which was closer to Patterson Park. The El Salvador Restaurant now on South Broadway was previously a jewelry store called the Hokahey Indian Trading Post. One of several Lumbee-owned auto shops in the area, Hunt’s Service Station, was also situated on South Broadway, right where a busy 7-Eleven store now sits. Today, coincidentally, it’s a hub for Mexican and Central American migrants seeking day labor employment.

A University of Maryland anthropologist who did fieldwork in the community described it in 1982 as “perhaps the single largest grouping of Indians from the same tribe in an American urban area.”

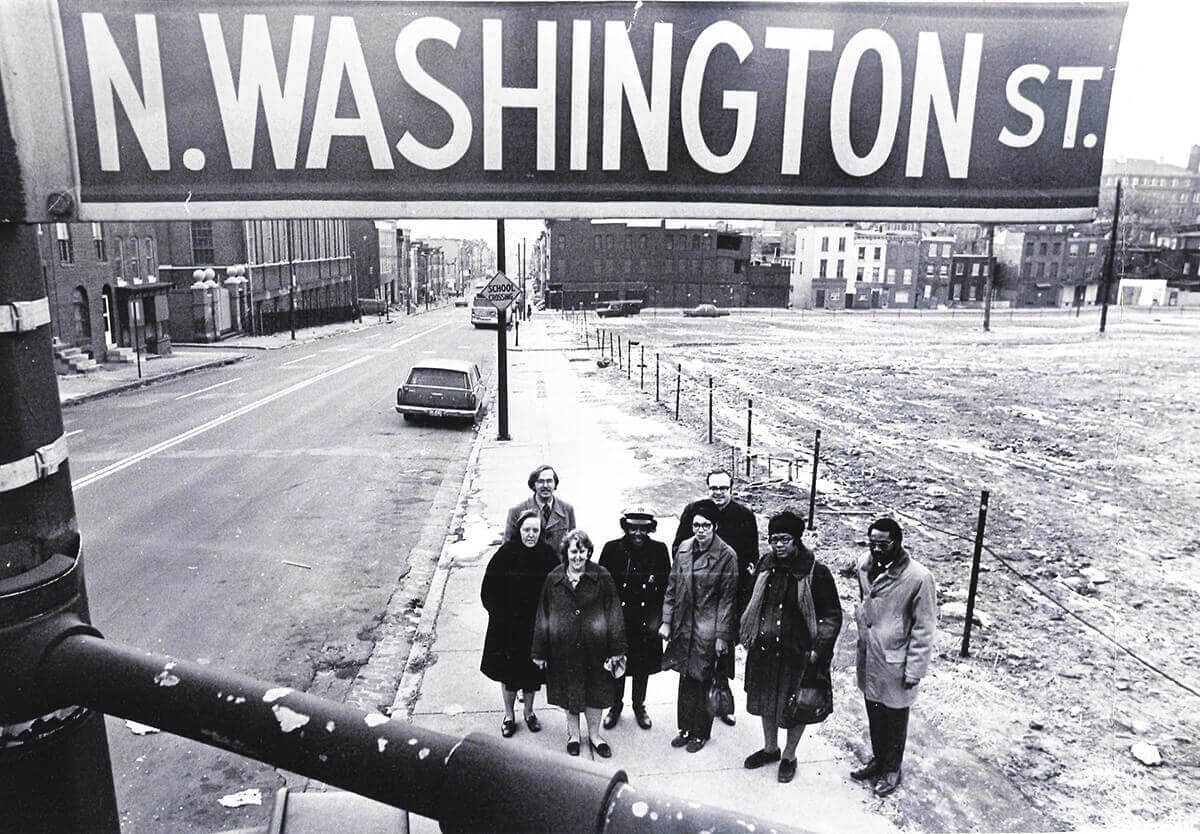

Members of an East Baltimore community group organized during urban renewal period, including Lumbee tribe member Rosie Hunt (center, fourth from left). Photo by Fred G. Kraft for 'The News American,' February 27. 1972. Courtesy of Hearst Corporation.

“Working at General Motors”—Lumbee tribe member Howard Redell Hunt Sr. Recorded by Ashley Minner

J ust a few decades later, almost all physical evidence of “the Reservation” has disappeared. Partly, it’s due to urban renewal efforts—the entire north side of the 1700 block of East Baltimore Street where Jones first lived was leveled and converted into a public park. Elsewhere, condominiums have gone up. And, like many other upwardly mobile, rowhouse- living Baltimoreans, Lumbees decamped for jobs, schools, and suburban homes in Baltimore County. Others returned to North Carolina as part of a wider reverse migration trend that began in the 1980s.

The main vestiges include the Baltimore American Indian Center on South Broadway and the South Broadway Baptist Church. Both were founded in the halcyon days of Indian activism in the late 1960s and remain active, with cultural classes and religious services.

But there are other holdovers.

“Slim’s Bench,” at the corner of East Baltimore and North Madeira streets—named for since-deceased Lumbee elder D.C. “Slim” Hunt, who resided nearby—endures as a near-daily gathering space for older tribe members.

Slightly further afield, Rose’s Bakery still makes downhome Southern favorites, which is to say traditional Lumbee cuisine—sweet potato pie, cornbread, banana pudding, collards, and chicken and pastry. Rose’s opened in the Northeast Market in 1978 and is heavily patronized by the local Lumbee community, most of whom now reside a few miles away in Dundalk, Middle River, Essex, and Rosedale. (At the 81st National Folk Festival this past August on the Eastern Shore, bakery owner Rosie Bowen demonstrated how to make collard green sandwiches, which are associated with Lumbee identity and memories of North Carolina and family. Collard sandwiches are a unique blend of Robeson County demographics and include Black, Indigenous, and white influences. Made with collards brought from Africa, fried cornbread from the Americas, and the fatback of hogs, which the Spanish carried to this continent in the 1500s—and often served with black-eyed peas—they’ve also been described as the perfect food to understand colonialism.)

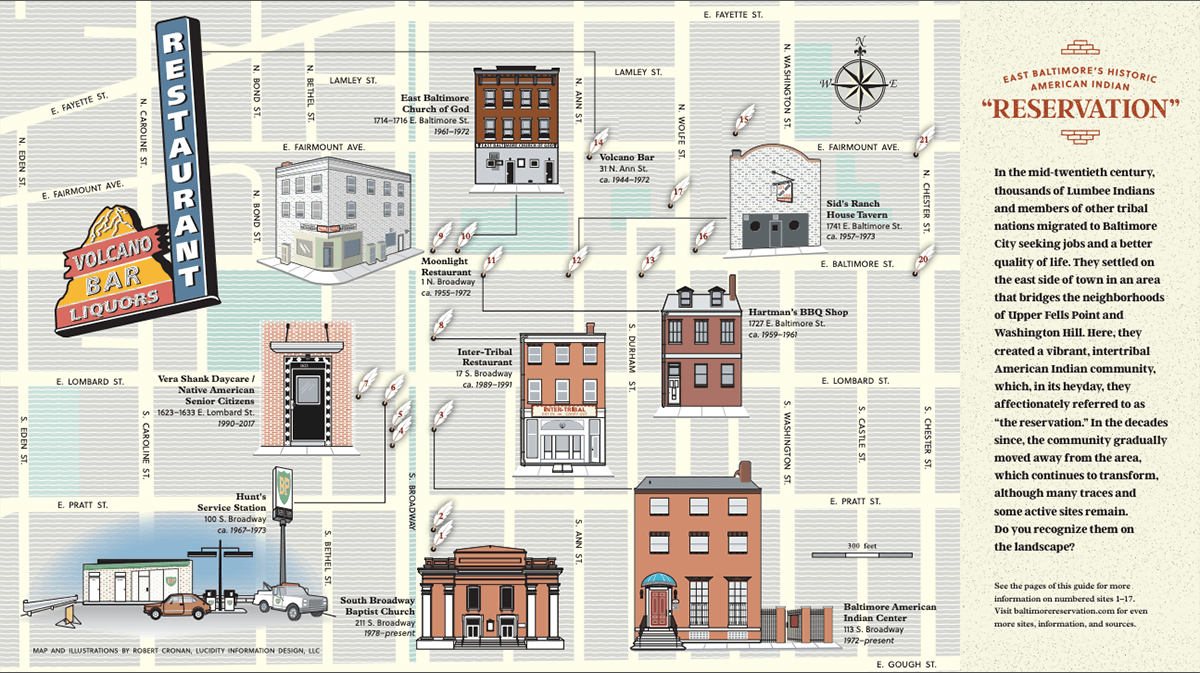

“The Lumbee community gradually spread out, so my own generation never experienced ‘the Reservation’ as such,” says 39-year-old artist and scholar Ashley Minner, a first-generation Baltimore tribal member born to a North Carolina Lumbee mother. “Over the last 17 years, especially, there’s been a sharp decline of Lumbee population in the city.” She estimates that perhaps a few hundred Lumbee reside in Baltimore City and a couple thousand more in Baltimore County. Minner, who grew up in Dundalk, has meticulously researched, documented, and archived the Lumbee journey, publishing a glossy walking tour map of the old Southeast Baltimore neighborhood last year and creating the informational website baltimorereservation. com. An assistant curator for History and Culture at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, her American Studies Ph.D. dissertation at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County explored the tribe’s history in Baltimore.

She is currently working with UMBC to establish a permanent Lumbee archive at the school, which will be named the Ashley Minner Collection and assembled within the Maryland Folklife Archives housed at UMBC’s Albin O. Kuhn Library. She is negotiating a book contract based on her dissertation and the urban Lumbee story in Baltimore, but with the sale of the Native American Senior Citizens building in 2017, she also feels like she’s in a race against time. “The remaining elders are in their 70s and 80s,” she says. “I do feel as if I arrived at this work at a critical juncture. The history is with the people. I wouldn’t know what to look for without the elders.”

Her efforts come at an interesting time in the broad arc of the story of Indigenous people and nations. Though this is their land, Native Americans are only now seeing their stories celebrated as part of the “American story” in mainstream culture.

Just last year, Baltimore celebrated its first Indigenous Peoples’ Day, becoming one of more than 50 cities and/or states to do so. President Biden issued the first-ever presidential proclamation of Indigenous Peoples’ Day last year, a significant shift away from the federal holiday honoring Christopher Columbus toward a celebration of Native peoples instead. (Also in 2021, Biden named former New Mexico Congresswoman Deb Haaland the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, making her the first Native American to serve as a cabinet secretary. He also appointed Charles Sams the director of the National Park Service, making him the first tribal citizen to serve in that role.)

More telling: A plethora of recent Native American-led and -cast television shows have been receiving rave reviews. The first season of Reservation Dogs on Hulu has been described as “a stereotype-smashing, Tarantino-esque triumph.” Peacock’s popular Rutherford Falls, co-created by a Native American, is for all intents and purposes, television’s first Native sitcom. The big budget Dark Winds, on AMC+, a long-awaited series with a Native American filmmaker directing most of the episodes, has also earned praise from viewers and critics. There are others, too: Mohawk Girls, Prey, Wild Indian, Montford: The Chicasaw Rancher, and Love and Fury—all on major streaming platforms, with more to come.

“I don’t call it a moment, because hopefully it lasts longer than that and it’s not something that comes and goes,” says Jody Cummings, an enrolled Lumbee member and lawyer, who has represented Native American tribes on natural resource issues. “But there is an increased profile, some because of people like basketball player Kyrie Irving embracing his mother’s Standing Rock Sioux heritage and some from the environmental issues [pipeline protests] in tribal communities, that hasn’t been there before. It’s a good thing.”

COVER AND SPREAD FROM A 1957 'EBONY' STORY ON BALTIMORE'S LUMBEE COMMUNITY. (THREE WOMAN ON THE COVER ARE CREOLE WOMEN FROM NEW ORLEANS.)—Sean Sohbot/Courtesy of Ashley Minner

M inner’s chronicling of the Baltimore Lumbee community and migration story started with her own family’s saga while she was still in high school. She began by recording her grandfather’s memories of North Carolina and Baltimore—long before she considered it an academic pursuit. He had decided to put his family farm in the rearview mirror after getting out of the U.S. Army and eventually brought his wife and three children—Minner's mother and her two brothers—to Baltimore. (One of Minner’s uncles had red hair as a child and got teased and harassed about it regularly when they moved here: There ain’t no red-haired Indians!) “I guess it was that fear of loss and realizing even at that age that people aren’t around forever,” Minner says of the early impetus for her research.

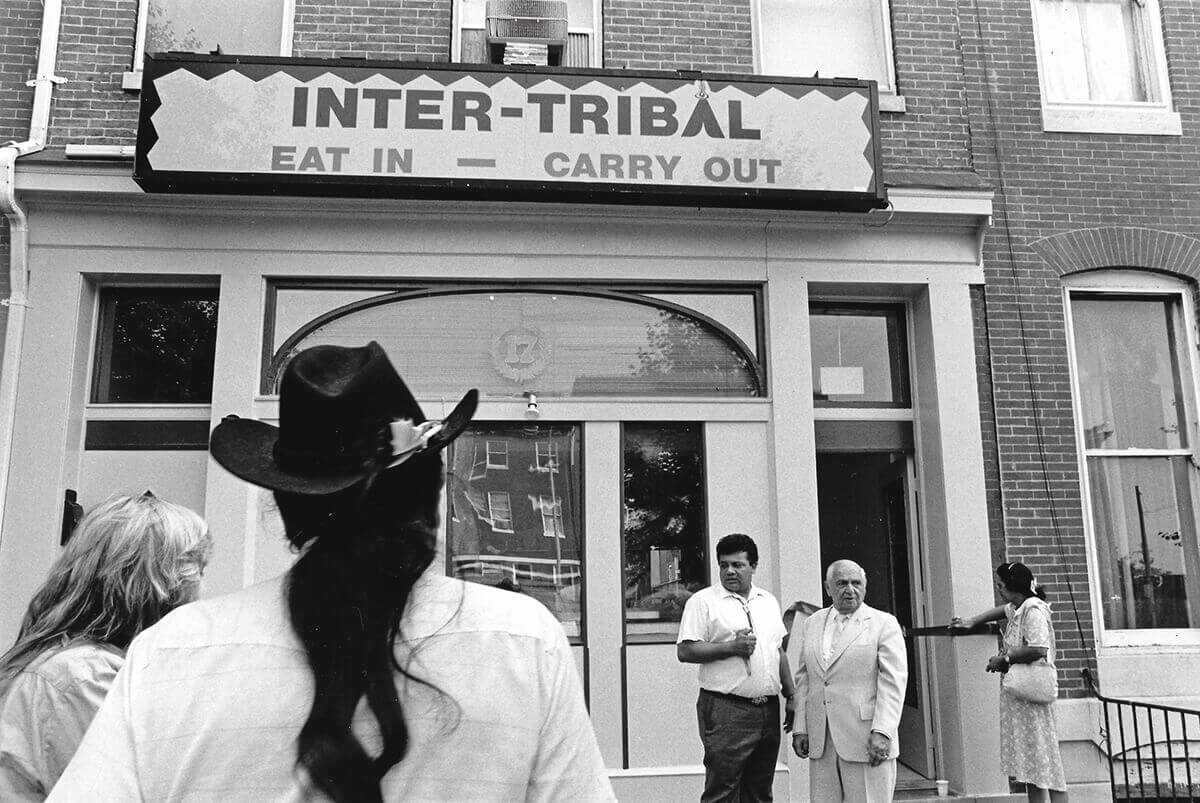

Former eatery in Upper Fells Point owned by the Baltimore American Indian Center. Courtesy of the Baltimore American Indian Center.

That was during a period in high school in which she struggled with her own often-mistaken identity, which is not unusual among first-generation tribal members in Baltimore. Displaced from their tribal roots in North Carolina, subsequent generations of Lumbee children often had a challenging time in city and county public schools, not easily fitting into Black or white cliques, or, more recently, Hispanic immigrant circles. Many faced harassment and bullying. It happens even today to Native American students in city and county schools. “I’ve been called Asian, Puerto Rican, Hawaiian—everything but what I am,” Minner says. “Then you tell people that you’re Indian, and they say, ‘No, you’re not.’ It does something to you psychologically to have people not accept you for who you are day in and day out.” Minner is Lumbee on her mother’s side and Anglo-American on her father’s side. Her husband, Thomas, is Lumbee and African American. The couple recently had their first child.

“Our young people can be particularly unmoored,” continues Minner, pausing and reflecting again on why she started collecting the stories of her elders and why they matter. “There are all kinds of ways society makes you feel like you don’t belong. I think when you realize that your history is much deeper than what you knew, it gives you a different sense of belonging. I think the archive could help with that. We are part of a long, rich history. We helped build this city. We helped develop the character it has now. It’s ours, too.”

Dean Cox, an ironworker by vocation and artist by avocation, is part of Minner’s generation. He remembers paper balls being thrown at him and running home to avoid getting jumped by classmates. “I didn’t want to keep telling my mom,” he says. “You fight back because you think that’ll work, but it doesn’t.”

Cox’s grandmother, Elizabeth Locklear, was one of the founders of the Baltimore American Indian Center. His mother, Linda Cox, 72, who was raised by her grandparents in North Carolina, still lives in the neighborhood, and currently serves as chair of the center. She also sings in the choir at South Broadway Baptist. “My mother wanted more out of life, but my grandparents would not let her bring me with her,” she says. “So I visited in the summer and then came to [permanently] stay in Baltimore when I was 18.”

The center, which has long offered traditional music, dance, and singing classes, and organized annual powwows—the 46th-annual BAIC Pow Wow is scheduled for November 19 at the Maryland State Fairgrounds—also supported youth sports, including a lacrosse team her son played on. (As Marylanders know, lacrosse was invented by Native Americans.) It became a refuge for the younger Cox and other Lumbee children. “You don’t think about these things consciously, but you go there to be with other Native American kids,” Cox says. “A couple of them lived nearby and you would hook up with them, and then the parents would know each other, too, and you’d go stay with them maybe on a weekend.”

Typically migrating from homes without indoor plumbing and sometimes electricity, the Lumbee community struggled with disproportionately high rates of poverty, alcoholism, drug addiction, and other health issues that often coincide with urban poverty. The center tried to address many of those needs over the years, hosting at various times job placement, housing, healthcare assistance, mentoring programs, entrepreneurial training, and alcoholism education on top of its cultural programming. “The center helped a lot of people,” Dean Cox says. “I was born into it. I’ve been a part of the center my whole life.” In 2015, Cox oversaw a restoration of the Indian-themed mural in the center’s courtyard, originally painted by center teenagers in 1980.

Despite the Baltimore American Indian Center’s half-century history, however, the mistaken identity continues.

“It’s guaranteed somebody’s going to walk up to me and speak Spanish every day," Cox says. “We can get used to anything as human beings, but if I’m talking about it, and if I’m being honest, it probably still bothers me.”

REFURBISHED MURAL AT THE BALTIMORE AMERICAN INDIAN CENTER ON BROADWAY IN UPPER FELLS POINT. PHOTOGRAPHY BY MIKE MORGAN

“Anyway”—Lumbee tribe member Rebecca Holmes Oxendine. Recorded by Ashley Minner

V ery much a segregated, if quickly industrializing, Southern city in the 1950s, Baltimore may seem like an unlikely destination for a person of color wishing to escape bigotry and systemic racism. Discrimination comes in varying degrees, however.

“They say Abraham Lincoln ended slave labor, but where I’m from, a small town called Red Springs in Robeson County, North Carolina, sharecropping just became another name for slavery,” says James Earl Locklear, standing outside the South Broadway Baptist Church in Upper Fells on a recent morning after services. The church, led by Rev. Bobby Joe Hunt, a Lumbee tribe member, has a Sunday school and roughly 100 members, including numerous Lumbee congregants, most of whom now commute from the county. “You rented the land and if you had an animal to pull the plow, you’d get to keep half the sales from the crops; if the owner supplied your animal, you’d get to keep a third,” Locklear continues. “And you bought sugar and coffee, cornmeal and things you needed like that, from the landowner’s store. Not a lot, because you also grew your own food. But no matter what, good year or bad, at the end of the year, you’d end up in the hole and if you tried to leave, they’d come after you.

“I was 17 when I left in 1959,” adds Locklear, who still cuts a striking figure at 80 years old in a suit jacket and bolo tie with an Indian pendant. “By then I was working on other people’s farms, picking tobacco, cotton, and corn, making $2.50 a day. I had an uncle already in Baltimore and he got me a job with a commercial painting company here making $3.25 hour. I thought I was rich,” he adds with a wry grin. “Then I discovered the bars in the neighborhood where you could spend that money.” (“The reservation” was also known for its sometimes rowdy local bars in the day.)

North Carolina Lumbee members wrapped in a captured KKK flag. 'Life' Magazine, Courtesy of the Charlotte Observer Photograph Collection, Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County.

More than six decades later, the racism he encountered even as a child in North Carolina is never far from the surface.

“When I was growing up, if you were Black or Native American, like me, and wanted to buy an ice cream, they’d only serve it to you in a cup. The cones were for white kids. That’s how they taught hatred to little kids.”

In fact, a year before Locklear left North Carolina, a Ku Klux Klan rally intended “to put the Indians in their place, to end race mixing,” in the words of its ringleader—shone a spotlight, literally, on Indian racism in Robeson County. The Klan had swelled in ranks following the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education desegregation decision. Although the Klan had typically targeted African Americans, in 1958 they began harassing the Lumbees. On the night of January 13, 1958, the KKK burned crosses on the front lawns of two Lumbee families. One of the crosses was burned in the yard of a Lumbee family that had recently moved into a predominantly white neighborhood. The other was intended to intimidate a Lumbee woman who was rumored to have been dating a white man. Five days later, the Klan rallied in a field in Robeson County.

It did not go as planned, but proved a demonstration of the tribe’s cohesiveness and tenacity. Reports differ regarding the exact number of Klan members, but it’s estimated around a hundred KKK supporters turned out. When their meeting began, however, the arc of their dim light didn’t spread far enough for the Klansmen to see that as many as a thousand Lumbees had surrounded them. Several young tribe members, some armed, closed on the rally, with a shotgun blast shattering the light from their generator. In the darkness, the Lumbees descended, yelling and firing guns into the air, scattering the overwhelmed Klansmen. Some left under police protection while others, including their new Grand Dragon, simply ran away. Considered one of the nation’s most dangerous organizations at the time, the Klan hadn’t kept the time and place of their rally a secret, and news photographers already on the scene captured images of exuberant Lumbees holding up the abandoned KKK banner, which were published around the world. Simeon Oxendine, a popular World War II veteran, appeared in Life magazine smiling and wrapped in the banner with another tribe member. Their rout became known as the Battle of Hayes Pond.

Nonetheless, Southern history remains an overwhelmingly Black and white narrative. Most Americans believe the genocide of Native Americans took place long, long ago. But it’s important to understand it was not completely successful, says Emory professor Malinda Maynor Lowery, a Lumbee tribe member and a former director of the Center for the Study of the American South at the University of North Carolina. “There are over six and a half million American Indians, and many of them live in the South,” she wrote in a New York Times opinion piece in 2018 following efforts to remove Confederate statues in several Southern states, including on the campus of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Lowery describes Indians as “the original Southerners” and stresses they continue to shape Southern history. She also links the genocide of Native Americans and the enslavement of Black Americans.

“American Indians often confronted both the North and South as enemies,” she noted. “The Confederacy’s commitment to slavery and the Union’s commitment to expansion were different versions of the same story of imperialism. Usually the last mention of us in K-12 classrooms is the Trail of Tears, when five Southern tribes were forced West in the 1830s.” Few people, even progressives, seem to recognize Native American presence in the South. The coalition organized to oppose the white supremacist Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017 did not invite any representatives of Virginia’s seven American Indian tribes to participate.

It’s worth mentioning it was not until 2012 that Maryland formally recognized the Piscataway Conoy Tribe and the Piscataway Indian Nation in southern Maryland, and 2018 for the Accohannock tribe of the Eastern Shore.

Photo for the occasion of the Baltimore American Indian Center winning the 2018 Maryland Heritage Award in the category of “Place.” (l-r Louis Campbell (Lumbee), Celest Swann (Powhatan), E. Keith Colston (Lumbee/Tuscarora). Courtesy of Edwin Remsberg

M eanwhile, the Lumbees actually remain in the middle of a nearly 140-year-old struggle for full recognition from the U.S. government. The tribe received state recognition from North Carolina in 1885, and a compromised recognition of sorts from the federal government in 1956—recognition without the full benefits accorded other tribes.

The bipartisan Lumbee Recognition Act, which President Biden has indicated he’d support, hasn’t gotten to his desk yet and remains pending in Congress. Other North Carolina tribes, notably the Cherokee, have opposed their campaign for full recognition—the assumption being they don’t wish to share the benefits that come with full tribal standing.

“The proposed legislation finishes the job Congress started in the 1956 Lumbee Act—full recognition, which frankly, our folks have been pushing for from the U.S. government since the late 1800s,” says Cummings.

The Baltimore American Indian Center in Upper Fells Point.Courtesy of University of Maryland Special Collections and University Archives, College Park, Maryland. Permission: Hearst Corporation.

To Milton Hunt, a diversity, equity, and inclusion consultant, leveling that field means everything. A Baltimore Lumbee with roots in North Carolina, Hunt highlights the fact that Native Americans represent the smallest minority in the U.S., making up roughly two percent of the population. “This is the first time in history that a Native American has been the secretary for the Department of Interior, which is responsible for the Bureau of Indian Affairs,” Hunt says. “We don’t have a sitting senator or Supreme Court judge. We haven’t had a president. We haven’t had the numbers to move the political needle by ourselves. The same has been true almost everywhere outside Oklahoma. Consider Baltimore, where we had 7,500 Native Americans at one time. Well, Baltimore had close to a million people then. We didn’t have anyone on the City Council. Representation has always been a struggle, and it’s kept us marginalized.”

Hunt, who is 61, credits the Indian Education outreach in city schools managed by Jeannette Walker Jones as life-saving for him. “I didn’t experience those things like ‘Colored,’ ‘Indian,’ and ‘White’ water fountains in North Carolina that I was told about, but I was called everything from ‘half-breed’ to the ‘N-word’ here,” he says. “I wouldn’t have graduated and was going to end up incarcerated and things like that. Today, I know that a true sense of identity, knowing who you are, that will get you through times when you are lost, especially when you’re young. What I learned from Jeanette, and she used older Indian students to mentor younger Indian kids with homework and everything else, was that it’s not who or what you say I am,” Hunt continues. “It’s who I know I am that matters.”

MAP OF THE HISTORIC LUMBEE COMMUNITY NEIGHBORHOOD IN SOUTHEAST BALTIMORE BY ROBERT CRONAN OF LUCIDITY INFORMATION DESIGN, LLC

Jessica Locklear, a Lumbee member and public historian from Philadelphia, says Lumbee migration from rural North Carolina to the crowded urban setting of industrial Baltimore has echoes of the Black migration story as well as the European immigration story. But she adds it’s important to keep in mind there are differences, and that the Lumbee migration story, like the story of other migrant/immigrant groups, shouldn’t be simplified to a single narrative. “Lumbee history is American history, and it’s rich and diverse and always connected to all the broader things happening in the U.S. The movement to Baltimore is a major part, but Lumbee also migrated in-state to cities like Greensboro. They settled in places like Georgia in the 1800s, forming communities that lasted 100 years, before returning to North Carolina. The Lumbees have evolved and survived by adapting to what was going on around them, and then often returning to North Carolina.”

To Locklear’s point, Lumbee tribe members’ profound connection to North Carolina, specifically the four southeastern counties of Robeson, Hoke, Cumberland, and Scotland, is unique and can’t be overstated. Baltimore may have become home for many, but North Carolina will forever be the homeland.

Rosie Bowen, the owner of Rose’s Bakery, still drives back and forth to North Carolina for her collard greens and the local cornmeal.

“It’s not the same from anywhere else,” she says with a smile, holding up a photograph of a patch of enormous collards from North Carolina from behind her bakery counter just hours before another trip to the place where her father was raised. “It’s funny, though, there are so many people from down there who came to Baltimore and returned home, that every time I tell people that I’m driving down, they start asking me bring them things—and the reverse.

“North Carolina and Lumbee family and friends in Baltimore want me to bring back collards and cornmeal,” she says, shaking her head and smiling again. “The family and friends who returned to North Carolina from Baltimore? They ask me to bring lump crab meat, Old Bay, and UTZ potato chips.”