Health & Wellness

RATS!

One city's long history with its most polarizing pest.

By Lydia Woolever

Photography Christopher Myers

Illustration by Eleanor Shakespeare

at the red-brick townhouse of Yvonne Richardson on a quiet corner in West Baltimore. Tucked behind Baker Street, away from the rushing traffic of Pennsylvania Avenue, there’s nothing but a patch of green grass and a lone municipal trash can, showing few signs of the bacchanal that breaks out here, night after night.

When the sun sets, a “mischief” of rats—that’s the term for a group of these rodents—emerges from beneath Richardson’s deck and along her wooden fence line. They skitter out into the evening, mingling with others in the adjacent alley, scuttling up and down its cracked asphalt, likely finding crumbs in empty bags of Utz potato chips or feasting on discarded chicken bones from the carry-out restaurant on the corner. In the standing water of puddles, they might wash it all down with a quick sip before dashing home before sunrise, out of the light, under the earth again.

ABOVE: JOSEPH WHITING OF DPW’S RAT RUBOUT TEAM ASSESSES THE AREA AROUND YVONNE RICHARDSON’S HOUSE. COLLAGE AT TOP: FISHING AND PETA. COURTESY OF THE MARYLAND CENTER FOR HISTORY AND CULTURE / BOX 8, FOLDER 2., PP284 AND FOLDER 1,PP284, JOSEPH KOHL PHOTOGRAPH COLLECTION. TRASH CANS, HOUSES, AND SIGN. COURTESY OF THE UB ARCHIVES. RATS. SHUTTERSTOCK. ALL OTHER PHOTOGRAPHY, CHRISTOPHER MYERS.

Rats are nocturnal creatures, making them a rare sight to see during the daytime. But not for Richardson, who feels quite literally taunted by them—meaning no morning coffees outside, no afternoon barbecues—their persistence causing her to lose sleep at night.

“Right here!” she exclaims, pointing from her back door to the ground below, recalling her last run-in. “About four of them, just sitting there, looking at me, like, ‘What’re you gonna do?’”

She’s called the city to complain countless times, and so, once again, on this hot July morning, three employees of the Department of Public Works (DPW) are on site, wearing long pants, N95 masks, and latex gloves, roaming the yard and inspecting neighboring properties.

“We look for evidence—holes, droppings, runways—rats run along fences and walls, they use their whiskers to help guide them,” says Donald Brooks, crew leader of DPW’s Rat Rubout team, rattling off characteristics of the city’s most ubiquitous pest like a field ecologist. But, of course, his presence here today is not simply for scientific purpose. “Our mission is seek and destroy,” he says.

His target? The brown rat, aka the Norway rat, aka the wharf rat, aka the sewer rat, aka Rattus norvegicus, which happens to be the primary rat species not only in Baltimore, but most cities of North America, where it not only survives but thrives in the worlds of our human creation, just as its ancestors have for centuries.

“Rats like what we like, they adapt to the environment they’re in,” says Brooks, noting the rodent’s affinity for both trash-strewn streets and splendid green spaces. “Their lifespan is only about a year, but they multiply so quick—they breed like 12 in a litter, and in like 90 days, babies can have babies,” with each female rat reproducing as many as seven times a year.

Do the math, and that’s a lot of rats. Not to mention a lot of work for DPW.

ANTHONY HALL, DONALD BROOKS, AND JOSEPH WHITING OF DPW’S RAT RUBOUT TEAM, WORKING IN WEST BALTIMORE.

After surveying the area, his colleague, Anthony Hall, drops a yellow sign into at least a dozen identified burrows, with thick black letters warning adults, children, and pets to CAUTION and KEEP OFF. Brooks and fellow pest-control worker Joseph Whiting follow behind him, and with a long plastic nozzle, pump a plume of white powdered poison into each. They toss in a pack of poisoned bait for good measure, then fill the hole back up with dirt.

The whole process takes just a few minutes, but over the next several days, the rats will meet a gruesome end. By then, though, the Rat Rubout team will already be off to other locations, addressing every city district at least once a month in what they call “proactive” inspections, and also responding to an endless slog of 3-1-1 calls from residents reporting rat issues. As of late October, they’d completed more than 109,985 visits for 2024.

And yet, despite their best efforts, the rat remains a cunning adversary. The DPW team tells tales of rats walking around those black plastic bait boxes, about them kicking packs of poisoned bait out of their burrows, about them chewing through lead and concrete. Which is why it’s no surprise that the city’s relatively new trash cans—like the kind in Richardson’s yard, made of a thick composite resin, part of a $9-million purchase in 2016 aimed at reducing litter and in turn abating rats—have not been a magic bullet. They’ve certainly helped, says Hall, but that’s only “as long as people use them properly.”

He nods toward an overflowing can on the street corner, its lid ajar, a large gash the size of a fist gnawed right through it. Often enough, the rats get inside, spooking the city’s sanitation workers as they leap to frantic freedom during weekly trash pickups.

And so, after today’s poisoning, it’s just a matter of time before a new brood is back at Richardson’s, once again bingeing on the alley’s bounty. DPW will then repeat their process. In fact, they’ve been visiting this block for years now.

“It’s a never-ending story,” says Brooks, who has worked with Rat Rubout for four decades. (The program itself dates to at least 1943, when it was known as the Rodent Control Bureau, then under the Bureau of Street Cleaning. Later, rat removal fell to the Department of Health, then the Department of Housing, before finding its way to DPW in 2003.)

And Hall, a former sanitation worker who grew up in this very community, knows that first-hand. As a kid, it was not unusual for him to walk in the house and find a rat inside. On the steps, on the stove, on the kitchen table.

“In Baltimore,” he says, matter-of-factly, “there’s always been rats.”

TRASH CANS LINE AN ALLEY BEHIND RESTAURANTS.

Of course, Baltimore is not the only city with rat problems.

Despite its name, the Norway rat hails from thousands of miles beyond Europe, said to have originated in East Asia some millions of years ago. At first, it likely lived along streams and dined on a respectable diet of seeds, fruits, and insects. But as humans evolved, establishing permanent settlements and developing agriculture, the opportunistic species formed a sort of codependency. Slowly but surely, they spread west, with us, eventually hopping aboard boats and hitching rides around the world, their tiny remains even discovered in shipwrecks. Unsurprising then, that they’d find their way to the port of Baltimore, probably making first landfall in North America around the Revolutionary War.

Today, rats are found in every U.S. state and on every continent except Antarctica—as far as we know. They’re considered to be the second-most common mammal on the planet, just after humans, but even then, it’s hard to tell, their populations so large, their nature so elusive, making them nearly impossible to count.

“One is occasionally in their presence without being aware of it,” wrote The New Yorker’s Joseph Mitchell in his seminal 1944 essay, “Thirty-Two Rats from Casablanca.” “In the whole city, relatively few blocks are entirely free of them.”

That’s why determining just how many rats live in any given metropolis is just a guessing game, with most estimates relying on the number of 3-1-1 calls—such as one website that recently ranked Washington, D.C., as the “Rat Capital” of the United States—or pest-control treatments, such as with Orkin’s annual list of America’s “rattiest cities.” This year, Chicago was ranked first, while Baltimore landed at a measly ninth—a personal affront to anyone who has ever cut through an alley or past a dumpster in this town. Let alone if you’ve ever had them living in your oven or walls.

Sure, rats might technically be more abundant in other cities, and New York certainly gets the lion’s share of attention, with its subway-scurrying, slice-dragging “Pizza Rat” being all but inducted into the internet’s viral-video Hall of Fame. But in Baltimore, rats have a certain omnipresence, invading everything from our vacant buildings to our fanciest restaurants, our nightly news to our national headlines, our pop-culture zeitgeist to our personal psyches. And as far as relationships go, it’s complicated.

The BALT rat bumper sticker.

Exhibit A: That infamous tweet five years ago, when then-President Donald Trump disdainfully declared Baltimore a “rat and rodent infested mess.” Baltimoreans were well aware of their rats, of course—didn’t like them, even hated them—but those were fighting words from a Manhattan billionaire.

“Give me the rats and roaches of Baltimore any day over the lies and racism of your Washington, Mr. Trump,” said local filmmaker John Waters within hours of the tweet, which specifically called out Maryland’s seventh congressional district, which then included both rural and wealthy suburbs—though clearly he meant the inner city, and its congressman, Elijah Cummings, a civil rights leader and son of sharecroppers who lived in majority-Black Madison Park. “Come on over to that neighborhood,” suggested Waters, “and see if you have the nerve to say it in person.”

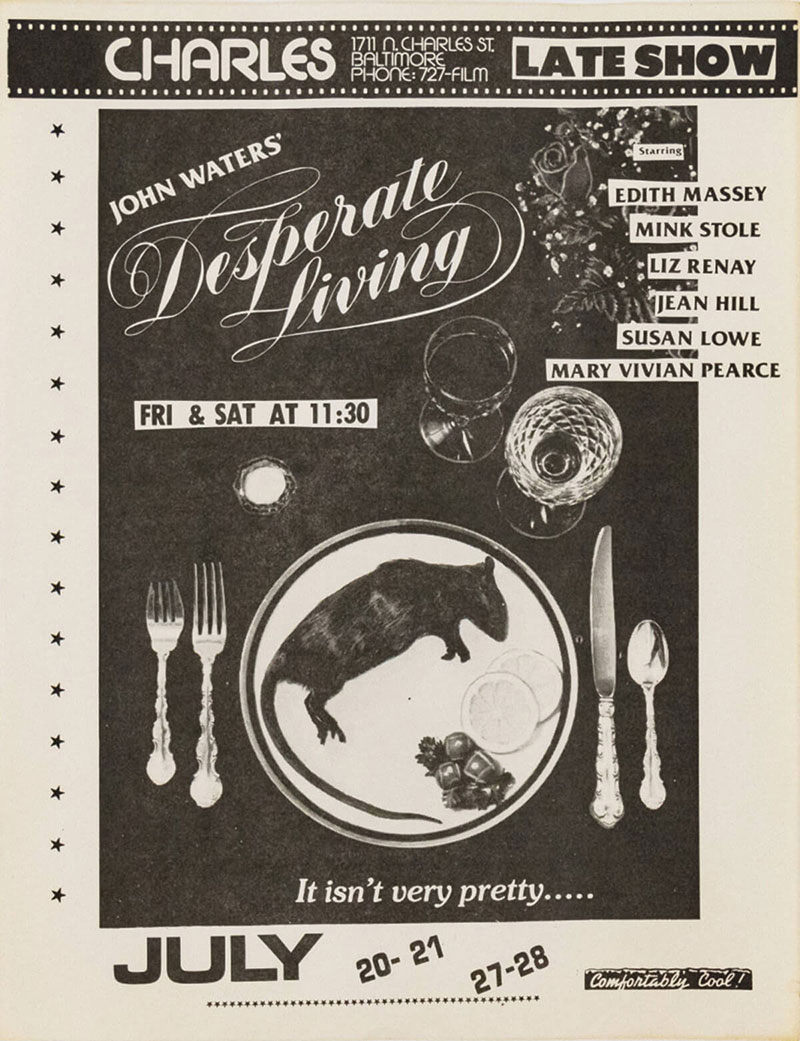

FLIER FOR A CHARLES THEATRE SCREENING OF DESPERATE LIVING BY JOHN WATERS, CIRCA 1977. © JOHN WATERS, “DESPERATE LIVING,” 1977, VINTAGE FLYER, 11 X 8.5 INCHES, COURTESY OF CLAMP, NEW YORK

Waters’ own iconoclastic films have featured plenty of rats—on the cover of Desperate Living, in that Pecker sex scene, as a mood killer during a kiss in Hairspray—meant to elicit their own kind of shock and awe. Gross, mischievous, irreverent, and oddly charming, his depiction of rats fit right in with his lovingly twisted vision of Baltimore, in all its contradictions and complexities.

In that same spirit, over the years, some Baltimoreans have even adopted the rat as an unlikely mascot, making it the namesake of underground music festivals (Ratscape), the subject matter of performance art (RATS! by the Baltimore Rock Opera Society), and, most notoriously, the star of a now-prolific bumper sticker, featuring a whiskered silhouette and four capital letters spelling BALT, commonly spotted around the hipsterfied likes of Hampden.

It’s a polarizing affection, given that Black neighborhoods are disproportionately impacted by rat infestations, where they are more than mere nuisance—the rodents being vectors of serious disease and socioeconomic stigma.

And yet it’s also a quintessentially Baltimore defense mechanism. The city’s underdog attitude is often entwined with an ironic and self-deprecating sense of humor. Instead of bemoaning our struggles, some are embraced like a badge of honor. As if to take ownership of those flaws. As if to control the narrative from outsiders who seek to judge. Which is particularly true of rats.

After all, having made it through plagues, world wars, and the industrialization of society, they are nothing if not survivors. Baltimoreans can relate.

Still, Trump’s rhetoric struck a nerve. That fall, when he visited the city for a Republican conference, protesters planted a giant inflatable rodent bearing his resemblance, on President Street no less—certainly not the first time a politician has been compared to a rat, but doubly significant in this instance.

“If there are problems here, rodents included, they are as much his responsibility as anyone’s, perhaps more because he holds the most powerful office in the land,” wrote The Baltimore Sun editorial board in 2019, in a piece titled “Better to Have a Few Rats Than to Be One.”

Of course, there are more than just “a few rats” in Baltimore. Decade after decade for more than a century, local officials have tried to tame their masses, and this spring, members of the city council renewed those same calls—part of a national wave of waging war against the rodent, their populations having especially proliferated during COVID.

But this time around, will it actually work?

FROM LEFT: THE CITY’S RELATIVELY NEW MUNICIPAL TRASH

CANS, MADE OF COMPOSITE RESIN; RATS ARE ABLE TO CLIMB WALLS, SQUEEZE THROUGH CREVICES, AND EVEN SWIM.

To understand Baltimore’s rat problem, one must first understand Baltimore’s rats. They like city life, with all its people, food, and shelter. They live underground, in an intricate network of burrows, typically in groups of about two dozen, rarely straying far from home. On any city block, there might be as many as 10 groups, meaning hundreds of rats; if some die, the population bounces back quickly—as “fecund as germs,” The New Yorker’s Mitchell adeptly described them. And it’s quite impressive, actually: A single female can spawn a whopping 15,000 descendants in a single year.

About a foot long and a pound heavy, brown rats are omnivores, and they do eat trash—lots of trash, loads of it. But they’re also paradoxically picky eaters—perhaps because they’re anatomically unable to vomit, making them suspicious of new foods, thus difficult to poison. They prefer to avoid people, too, but will attack when cornered, their jaws strong, their teeth sharp, their agile bodies able to leap distances of several feet. They can also climb walls and squeeze through crevices. And they’re surprisingly strong swimmers.

Also contrary to popular belief, rats are clean freaks, spending hours each day grooming. But still, their cousin, the black rat has long been blamed for the Black Death of the Middle Ages, and our own brown rats are plenty dangerous. They carry lice and mites, as well as an array of illnesses that can be transferred to humans by way of flea, tick, bite, or feces—things like bubonic plague, salmonella, and typhus, to name a few. They’re also destructive—spreading debris, scarfing down drywall, destroying car wiring, at times starting house fires—causing billions of dollars in damages around the world each year.

And in many ways, they’re not all that different from us, either (more on that later), which is why they’ve become the second-most popular laboratory specimen after mice.

Throughout much of the 20th century, Baltimore was the epicenter of rat research, with the “golden age” of such science led by Johns Hopkins University ecologists David E. Davis and John B. Calhoun into the 1950s. Their extensive lab and field studies “remain the best source of information available for many aspects of rat biology,” wrote the authors of a new paper published in September’s rat-themed issue of the prestigious academic journal, Science. But all that actually began here even earlier.

Rats first made their way up the Chesapeake Bay and Patapsco River around the 1700s. On land, the rodents multiplied between the city’s wharves, warehouses, and narrow rowhomes, inspiring mom-and-pop exterminators to take out advertisements in the local newspapers as early as 1846. But no real dent would be made for another century, when, in 1942, Hopkins School of Medicine psychobiologist Curt P. Richter, later known as the “Pied Piper of Baltimore,” accidentally discovered a lethal compound that lab rats couldn’t taste.

And it was perfect timing. In the midst of World War II, Allied powers feared the Axis might use rodents as biological weapons. A key ingredient in the day’s most popular rodenticide then hailed from the war-torn Mediterranean, and in their scramble to find a substitute, the U.S. government employed Richter to test his new concoction in the back alleys of East Baltimore, then heavily populated by low-income Black residents.

The results were “quite encouraging,” wrote Richter in his 1968 memoir, Experiences of a Reluctant Rat-Catcher. Soon enough, he was hired by city hall. And over the next few years, his Rodent Control Project—the earliest predecessor of today’s Rat Rubout—baited the city from end to end, killing 900 rats at Lexington Market in a single evening, and well over one million when all said and done.

Effective? Evidently. Harmless? Not so much. Pets died. Children had their stomachs pumped. And after all that, young rats started to grow wary, eventually avoiding the poison entirely.

Enter the aforementioned Davis, who would take a far more holistic approach into the 1950s. Part of Hopkins School of Public Health, he instead focused on the role of habitat, believing “if you could control the environment, you could control the behavior,” explain Jon Adams and Edmund Ramsden in their new book, Rat City, and thus limit the population size, perhaps even permanently.

His Rodent Ecology Project also coincided with the Baltimore Plan, an urban rehabilitation effort run by the city’s Health Department, which, through infrastructure improvements and code enforcement, intended to address its ailing neighborhoods.

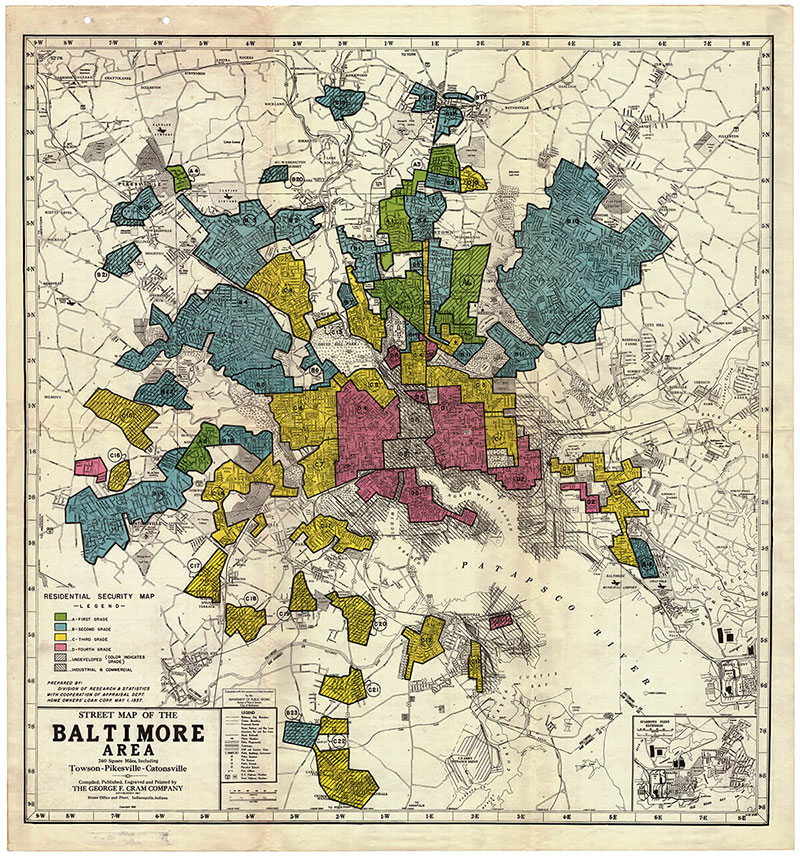

Over the previous decades, through periods of immigration, urbanization, and industrial boom, low-income and predominantly Black residents had been crammed into overcrowded districts, riddled with dilapidated lodgings, deadly disease, and pervasive pests—each a byproduct of the city’s even longer legacy of racial segregation. In the aftermath of the Civil War, Baltimore had codified its Southern sympathies—from passing the nation’s first law prohibiting Black people from moving into white neighborhoods to enacting a slew of redlining real-estate practices and Jim Crow housing policies, which used factors like race and class to gauge risk and value. White neighborhoods were deemed “green,” while all but two Black neighborhoods were “red,” writes Antero Pietila in Not in My Neighborhood, “leaving behind a lasting stigma.” With limited housing options and no shortage of exploitative landlords, a vicious cycle of government-sanctioned discrimination and deterioration followed. Aka a Shangri-la for rats.

“Rats filled the niche created by the forces of racism and disinvestment,” writes Dawn Biehler, associate professor at University of Maryland, Baltimore County, in her 2013 book Pests in the City. “Where disrepair was widespread throughout a building, block, or neighborhood, rats became entrenched residents.”

The Rodent Ecology Project saw only one solution: restricting the rodent’s access to food and shelter, a process that just so happened to be getting underway with the Baltimore Plan. “An all-out attack on bad housing conditions,” summarized The Sun in 1954—clearing yards, replacing fences, repairing windows, installing indoor toilets, sealing cellars, removing trash—“will reduce, possibly to zero, the number of rats in a neighborhood.” Because give them an inch, rats will take an entire block.

And it worked. For a while, at least. Little by little, landlords were forced to clean up. The city’s “sanitation squad” reported noncompliance. Property owners who couldn’t afford repairs were helped with funds. But over time, resources dried up, and the Plan dwindled. In its final years, organizers advocated for the creation of a new municipal agency to oversee the extensive and multi-pronged undertaking. But the city denied.

You see, politicians had already moved on, their attention now focused on the shiny new federal dollars of “urban renewal,” which meant instead demolishing those degraded homes and replacing them with public-housing projects that further displaced and segregated Black families (while also disturbing underground rat dens). Poor construction and inadequate maintenance only intensified inequalities for resource-strapped residents, and once more primed conditions for pests.

And as blight bubbled up again in Baltimore, so did tensions across America. “Rats cause riots!” chanted protesters on Capitol Hill in 1967. The House of Representatives had just blocked President Lyndon Johnson’s Rat Extermination Act, which would’ve provided $40 million for urban rodent control, part of a broader housing rehabilitation program. At the time, both experts and those engaged in the Civil Rights Movement knew that conditions like rat infestations were symptoms of larger systemic problems. But opponents blamed individual residents, their racist innuendo obvious as they openly mocked the legislation as a “civil rats bill.” Ironically, Congress was then spending $5,000 a year to keep its marble halls free of those very rodents.

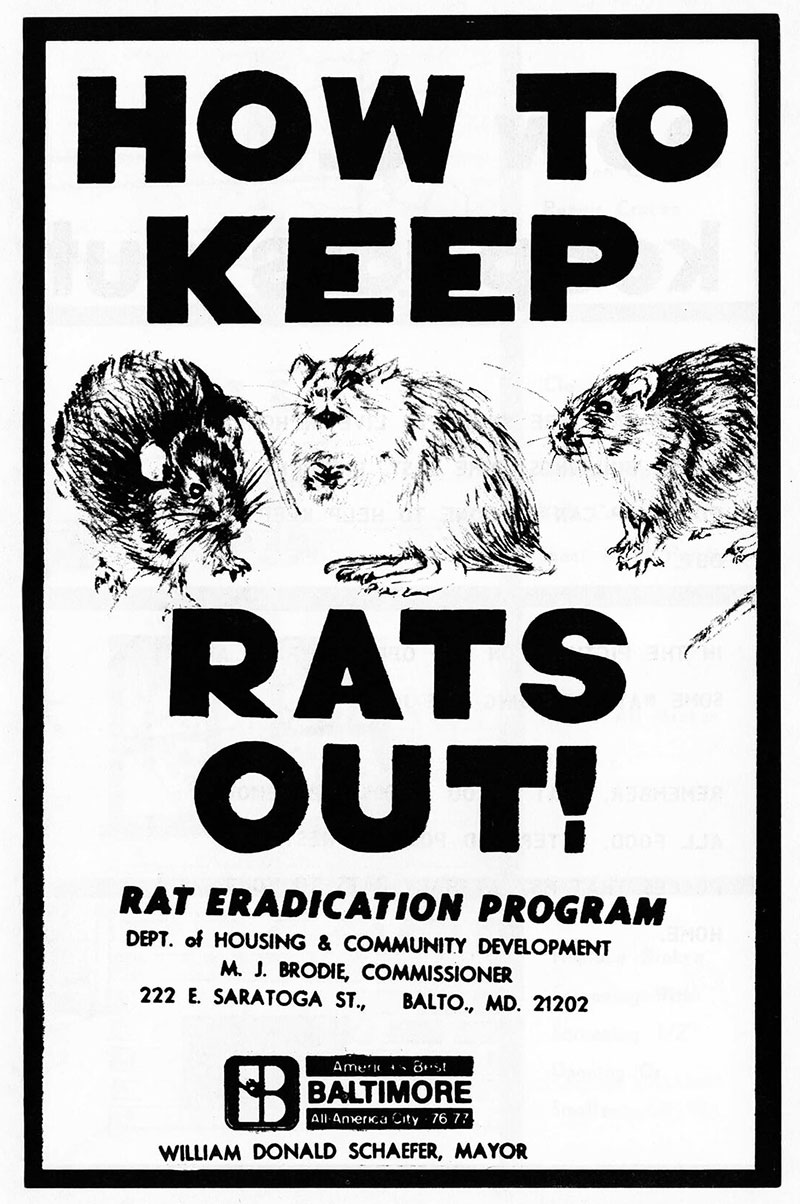

Back in Baltimore, the same battle raged on, and poison returned as the primary weapon. Throughout the second half of the 20th century, the city’s rat control efforts ebbed and flowed with inconsistent staff and funding. And so when the vermin humiliatingly devoured a 3,000-pound cake baked for the city’s big bicentennial celebration in the 1970s, Mayor William Donald Schaefer had had enough. Trying to bring things back from the brink, he threw a city-wide “Trash Bash,” bought a $10,000 “rat van,” and hired the Baltimore Theatre Project to perform a rat-themed educational drama at local elementary schools. But none of it stopped them.

By 1991, things had gotten so bad that some residents even reported the rodents swimming up their toilets. “If you accompany Rat Rubout workers on their poisoning rounds, you realize the city will never rub out all the rats in Baltimore,” wrote The Sun that year. “You get the impression that if Rubout bombardiers dropped a nuclear bomb over certain alleyways in the morning, people would die right away, but the rats would come out that night.”

Not that Baltimoreans would go out without a fight.

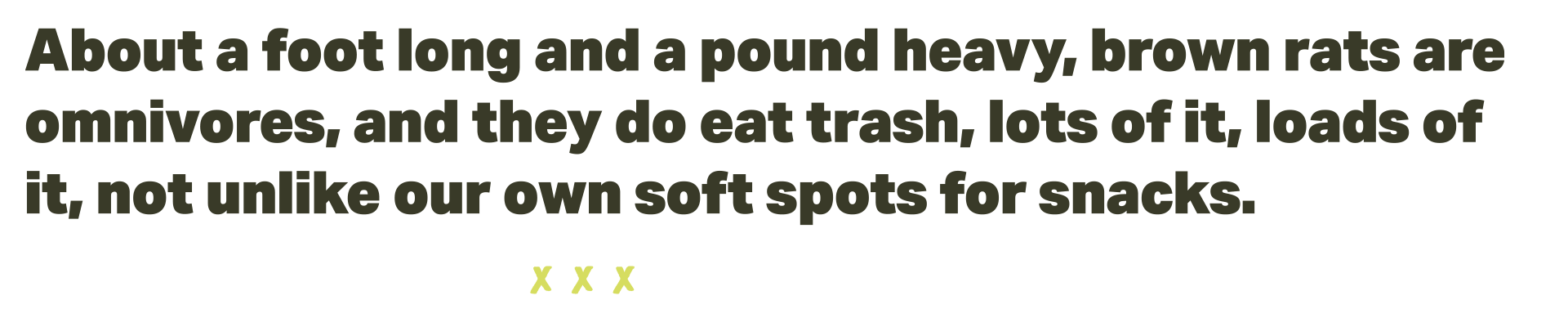

WILLIAM DONALD SCHAEFER POSING WITH NEIGHBORS AND HIS “TRASHBALL” PUBLICITY TRUCK, 1974; THE B.A.R.F. TOURNAMENT, 1994; THE AFRO CLEAN BLOCK CONTEST ON GILMOR STREET, 1945. COURTESY OF THE MARYLAND STATE ARCHIVES; THE MARYLAND CENTER FOR HISTORY AND CULTURE / BOX 8, FOLDER 2., PP284 JOSEPH KOHL PHOTOGRAPH COLLECTION; THE AFRO AMERICAN NEWSPAPERS ARCHIVES

On a late-spring weekend in 1995, a peculiar tournament was underway on a residential corner of Fayette Street in East Baltimore, two blocks north of Patterson Park. For the past three years, contestants had gathered at the Yellow Rose Saloon, carrying rods, reels, and a hodgepodge of bait, including peanut butter and bacon. Inside the bar, they purchased three-dollar fishing licenses from B.A.R.F., aka the Baltimore Association of Rat Fisherpersons, and over the course of the next two days, cast their lines down the littered alleys in hopes of landing the largest rodent. That year, the top prize would weigh in at one pound, seven-and-a-half ounces, and more than 13 inches in length.

As ZZ Top blasted from the jukebox, onlookers, reporters, and animal-rights activists watched with awe and disgust. Once reeled in, the rats were beaten to death by a baseball bat—a demise that participants argued was still more humane than the city’s poison, then and now an anticoagulant, which essentially causes the creatures to bleed out over several days. And after all, they had a higher purpose, hoping to bring attention to this working-class neighborhood, beleaguered by crime, trash, and pests. All in all, a brutal but civic-minded stunt.

“It’s not one of the best neighborhoods in the world,” said Chuck Ochlech to The New York Times, the streets around the self-proclaimed “Ratman” scattered with smashed televisions, soiled diapers, and rotting garbage. “But we got to live here, and we’re doing what we can.”

EDUCATIONAL MATERIALS FROM MAYOR WILLIAM DONALD SCHAEFER’S RAT ERADICATION PROGRAM. —COLLECTION OF THE MARYLAND STATE ARCHIVES

At that point, communities were accustomed to taking matters into their own hands. After decades of failed promises, residents had gotten creative, with grassroots efforts ranging from educational campaigns to neighborhood street sweeps. Dating back to 1934, the Afro-American newspaper hosted an annual Clean Block competition, encouraging young people to scrubs stoops, paint doorways, and plant flowers for the chance to win a party. In the early ’80s, the Remington Improvement Association organized a three-year blitz, enlisting locals to poison burrows, collect garbage, and purchase trash cans, capping it all off with a “rat bash” at the corner church, during which kids pummeled a rat-shaped piñata named “Ratso.”

And then there were the vigilante residents who made it their personal crusade. Like Rosia McDaniel, known as “Mrs. Mac,” a nurse-turned-exterminator, who would hunt them down around Park Heights, poisoning some 14,000 rodents in a single month. She was known to grab them by her bare hands, iconically telling one Sun reporter, “They wouldn’t dare bite me.”

This is the same kind of cold-blooded heroism that helped Matthew Fouse rise to rat stardom in the 2000s. As a young adult, the Hampden resident spent evenings on the back porch of his Falls Road rowhome, drinking Natty Boh and using a pellet gun to plink off the panoply of rodents that tiptoed up and down his alley. (This was technically illegal, though the cops didn’t seem to care.) And when he moved to Abell a few years later, the hobby became a community affair.

“At first, the neighbors were scared to death,” says Fouse, a Pennsylvania native and lifelong hunter, but eventually they started calling to request his services, with a few even joining his ad-hoc neighborhood patrol. Some nights, they’d kill one. Other nights, they’d massacre 20. As a joke, he designed the group a logo and printed it on T-shirts. Those got so popular, he wound up selling them at local stores, and before long, the city’s most iconic bumper sticker was born.

“I never thought it would become what it is today,” says Fouse, who’s sold over a million stickers in all 50 states, earning him the nickname of “Rat Czar” along the way. “In the beginning, I’d get so excited to see one on the street. But then they started to look like rats—they were everywhere.”

Now you can find that BALT rat bumper sticker plastered on car tailgates, telephone poles, dive-bar bathroom stalls, Nalgene bottles—even tattooed onto the skin of some diehard fans. There’s also a limited edition, created after Trump’s tweet, featuring the rat in that well-known hairdo above the White House address. Fouse donated all proceeds to a local charity.

“Of course, a lot of hate came with it, too,” he says.

Indeed, the sticker has become divisive, critiqued for its insensitivity to the city’s deeply entrenched inequities, often sported by white hipsters but rarely if ever seen in the Black communities that deal with the worst rats. A 2016 Hopkins study linked rodent infestations in low-income neighborhoods with feelings of depression and distress. In other words, not all pests are equal, and maybe it’s easier to make light of a problem that’s not really yours.

“Anyone can cross paths with a rat, on the street, in their trash, even in their home,” says UMBC’s Biehler, “but the real difference is, how easy is it for you to get rid of them?”

Standing at the edge of his old alley off 33rd Street in early fall—its trash cans recently emptied—Fouse vows that he’s only ever had good intentions, be it uniting Baltimoreans over their common foe, or in giving everyone else the middle finger. “I hope the sticker can be a meeting point, and a sense of pride. Like, ‘Yeah, we’ve got our problems, and yeah, we’ve got our rats. But this is still a great fucking town,’” he says.

Suddenly, his eyes light up.

“Speaking of!” exclaims the Rat Czar, pointing to the neighbor’s fence line.

In the middle of broad daylight, a small brown rat rounds the corner, then disappears.

“RAT CZAR” MATT FOUSE POSES WITH A PELLET GUN AT HIS OLD HOUSE IN ABELL; GRAFFITI ART DEPICTS A RED CARPET FOR RATS TO THE SEWER.

Today, no one knows exactly how many rats live in Baltimore. But over the decades, a few surveys have attempted a census. In 1952, Davis, of Hopkins’ Rodent Ecology Project, estimated the city’s rat population to be about 48,000, though he admitted it was surely higher. Then in 2004, despite all that came after, experts surmised that those numbers hadn’t changed. By all accounts, it seems there are no fewer rodents today than there were some 75 years ago. If anything, there might be more.

Right now, the city has at least 13,000 vacant buildings, and another 20,000 vacant lots, with each abandoned property providing ample shelter for rats—the vast majority of them situated in the so-called “Black Butterfly.”

Coined by Morgan State University public-health researcher Lawrence T. Brown in his 2021 book of the same name, the “Black Butterfly” refers to the geographic areas to the east and west of downtown Baltimore. But more than just where Black residents are physically clustered—on either side of the central “White L”—it also reveals, both in the past and present, “where capital is denied and structural disadvantages have accumulated,” says Brown—the same communities that had been redlined all those years ago, enduring in a tangled web of political, economic, and environmental injustices for well over a century.

It’s no coincidence, then, that these are the same communities who suffer the brunt of illegal dumping and other litter issues. Or where, as a 2019 Sun analysis revealed, response times to 3-1-1 calls for dirty alleys disproportionately lag. And so it’s not simply bad luck that these parts of town also struggle the most with rats, or illnesses associated with them, like asthma.

1935 REDLINING MAP OF BALTIMORE, CREATED BY THE HOME OWNERS LOAN CORPORATION, FORESHADOWING THE LINES OF THE BLACK BUTTERFLY. —COURTESY OF SHERIDAN LIBRARIES, JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY.

District 13—which includes majority-Black neighborhoods like McElderry Park and Middle East—receives the most Rat Rubout visits, a total of 17,439 as of press time in late 2024. But even that doesn’t tell the entire story. In District 7—where Richardson lives, which has received 7,555 visits, and was also ground zero for the city’s uprising following the police-related death of Freddie Gray a decade ago—the DPW team knows that there are persistent rat issues that simply aren’t reported.

“In the entirety of Sandtown, we only get a handful of calls,” says Rat Rubout’s Joseph Whiting, with the department receiving only 298 in 2023. “We try to tell people, it’s a free service, call as much as you want.”

Some of his colleagues call it apathy, but Whiting recognizes a sense of despair, recalling one elderly resident whose backyard, despite multiple treatments, still teemed with rat burrows. “I said, ‘How do you take the trash out?’ And she said, ‘Baby, I don’t . . .’ She had to walk it all the way around her block. These guys get on me, but I was almost in tears. You can’t help but take it personally.”

With an annual operating budget of $1 million, his 12-person team can only do so much. Rat Rubout also engages neighbors and leaves informational fliers, but they can’t just spray indiscriminately, requiring a resident’s permission to bait a property with Ditrac, the poison being toxic to humans, pets, and wildlife. And even when they do, their efforts are just a Band-Aid, especially in streets already strained with trash and vacants. The team reports those violations to the Department of Housing, which issues citations. But they can’t guarantee that landlords will pay them. And for some residents who own their homes, it’s an unaffordable expense.

“At that point, all we’re doing is hurting the poor more,” says DPW’s Hall. “It’s damned if you do, damned if you don’t.”

Every few years, though, local politicians show up and demand that something must be done about this. The current call-to-arms comes on the heels of New York City’s Mayor Eric Adams, who, despite his recent federal indictment, is leading a full-on assault against Manhattan’s rats. To that end, he hired the first-ever “director of rodent mitigation,” hosted a national “Rat Summit” of elected officials and experts, and created an online “rat information portal” for the general public. Then this fall, their city council passed a bill that would try another tactic: birth control.

Down I-95, back in Baltimore, this piqued the interest of city councilwoman Phylicia Porter, whose District 10, from Westport to Curtis Bay, is mired in not just trash and rats but additional health hazards related to its waterfront coal terminal and waste incinerators. And so earlier this year, she initiated a hearing between several city agencies and the council’s Health, Environment, and Technology Committee on the state of rat abatement.

“I want to emphasize that having a clean and healthy neighborhood is a fundamental right that our constituents deserve,” said Porter during her opening remarks in September. Over the next 50 minutes, efforts were reviewed, experiences were shared, and ideas were discussed, ranging from the familiar— increased community engagement, improved inter-agency collaboration—to the novel, including automatic resident consent for Rat Rubout treatments and that newly popular rodent contraceptive, known as ContraPest.

CITY

COUNCILWOMAN

PHYLICIA PORTER,

WHO IS LEADING

THE CURRENT

CONVERSATION ON

RATS.

Previously piloted in other cities like Boston and Chicago, the edible EPA-approved formula works by temporarily restricting fertility in both female and male rats, effectively reducing birth rates, just long enough to hopefully increase the impact of Rat Rubout. Distributed in protected boxes, it has a salty-sweet flavor that entices the rodents. DPW received one preliminary demonstration from the parent company in 2018. At the end of 2024, they ordered the first batch of product to initiate a pilot program. As of press time, there was no confirmed start date for its implementation.

Whether it works or not remains to be seen. After all, time and time again throughout the September hearing, trash was called out as the primary culprit. As long as it overflows, everyone seems to know, so too will the rats. Which ultimately raises the age-old question: Who bears more responsibility—individuals or their government? Unsurprisingly, fingers get pointed. More often than not, it’s dismissed as a “people problem.”

“That’s the softer version of a long history of stigmatizing people as rodents—of course Donald Trump being the most recent example of that,” says Lawrence Brown, also citing the city government’s own Municipal Journal, which referred to Black homes as “pest holes” in 1917. “If you say that people are responsible, you’re basically excusing the policies, practices, systems, and budgets that are really behind the conditions in which they live. It’s a way of erasing what’s really happening, and presenting the victims as the villains.”

What everyone can seem to agree on, though, is the sentiment that was shared by Councilwoman Danielle McCray, representing District 2 neighborhoods like Belair-Edison and Highlandtown, toward the end of the hearing: “What we’re doing right now, it’s not enough . . . it’s not enough.”

In addition to Rat Rubout, DPW oversees the city’s sanitation efforts: residential trash and recycling, street and alley cleaning, and lot maintenance (high grass being another hiding place for rats). More than 200,000 tons of waste move through Baltimore annually, not counting the estimated 10,000 tons in illegal dumping. And while officials claim those municipal trash cans have helped, residents still report unreliable weekly pickup, once again along the same socioeconomic lines. Surely the inconsistent recycling during COVID didn’t help, either, when private pest-control companies also noticed a sharp uptick in business.

In its new 10-year plan, DPW lists larger crews, local business outreach, and the hiring of resident litter squads among its opportunities for growth. Meanwhile, Mayor Brandon Scott continues to host his annual spring and fall cleanups, and the city’s BMORE Beautiful program supports local communities through microgrants, adopt-a-lots, and environmental stewardship projects for youth. For his part, Governor Wes Moore wants to revamp 5,000 vacants over the next five years. And if history has taught us anything, it’s that rats will require a wide range of both immediate and sustained solutions.

“This is not an issue that is going to be solved by one strategy alone,” says Porter, an Edmondson Village native and Pigtown resident. Instead, she supports a three-tiered approach of community engagement, improved trash disposal, and ContraPest. “When we have a sanitation issue, a vacant housing issue, an absentee landlord issue, that is all connected to the rodent population and how it is proliferating throughout the city of Baltimore. . . . We have a lot of work to do.”

Still, she gets why residents might be skeptical about lasting results. The next council committee meeting is not yet on the books, and Baltimore has a tarnished track record when it comes to the follow-through of its elected officials.

In 2017, for example, Mayor Catherine Pugh launched HEAL, aka the clunkily named Healthy Elimination of All-pests Long-term, which continues to provide exterminations for a dozen public-housing developments throughout the city. But a year and a half after the program’s launch, Pugh resigned as mayor amid an unrelated scandal, which involved receiving special treatment from the University of Maryland Medical System.

In a fitting twist, one of their board members, Walter Tilley—a campaign donor who flew Pugh to a Las Vegas conference on his private jet—just so happens to own one of the region’s most popular pest-control companies, which was contracted for HEAL. At one point during her tenure, she even knighted him as the city’s “Honorary Rat Catcher.”

Today, one in three public-housing developments in Baltimore fails to meet federal inspection, according to a recent analysis from The Baltimore Banner, with rodents still cited as one of their many health and safety concerns.

DEAD RATS

ARE A COMMON

SIGHT ON THE CITY

STREETS; A MURAL

IN HAMPDEN

INCLUDES MISCHIEVOUS

RATS.

Throughout his research in the 1950s, John B. Calhoun— a protégé of Hopkins’ Davis—got certifiably hooked on rats. As their Rodent Ecology Project wrapped, he took what he’d learned in the streets of Baltimore, built a tiny replica block on an empty lot behind his house near Towson, and for the next two years, from a plywood observation tower, meticulously watched the creatures’ every move. His findings remain “the most comprehensive and complete account of rodent behavior ever produced,” write Adams and Ramsden in Rat City, noting that Calhoun knew more about this particular critter “than anyone else alive.”

Some of that, though, would come to haunt him. In his experiments, he found that rats built fairly civil worlds, but as conditions became overcrowded, things took a more dystopian turn, leading to societal breakdowns—interpreted by some as a warning for humanity. On the brighter side, his work inspired the classic children’s novel, Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH, earned him a consideration for the Nobel Prize, and influenced generations of scientists to come. He was also a muse for local filmmaker Theo Anthony’s much-buzzed-about Rat Film documentary in 2016, the soundtrack of which was created by local composer Dan Deacon using live rats.

The soundtrack for Rat Film, by local artist Dan Deacon, who crafted each song with the help of live rats.

Today, at the same time that hundreds of thousands of rats are killed by cities each year, hundreds of thousands more are bred to be used in labs across the U.S., including plenty at Hopkins. They were the first mammals to be domesticated for research purposes, dating back to the 1800s, and over the centuries that followed, have become medical marvels.

It turns out, many of our own characteristics closely resemble those of rats, and symptoms of our conditions can be replicated within them, making the rodent one of our most important model organisms. So while they wreak their havoc on our societies, they’ve also yielded invaluable contributions to our health and well-being, from cancer research to organ transplantation to a better understanding of psychedelic drugs—along the way saving countless human lives.

“They are likely to remain our companions,” wrote Science in September. “A better understanding of this, and their nature, will help us minimize their negative impacts and appreciate what they still have to teach us.” The academic journal would also go on to advocate for more ethical welfare considerations for rodents used in scientific research.

That’s in part because recent studies have discovered that rats are not only smart and social, but also that they show evidence of empathy and altruism. That they console one another, help friends in trouble, and, after enough time together, even extend the same kindness to strangers. That they understand rules and make plans. That they recall memories. That they feel regret—and maybe hope. They’ve even learned how to drive tiny vehicles. And to play hide-and-seek with their researchers.

No wonder for centuries we’ve also kept the pests as pets.

They’re ticklish. They like to snuggle. They even dream.

Toward the end of John Waters’ 1990 film, Cry-Baby, the namesake character, played by actor Johnny Depp, is stuck in prison. Dressed in a black-and-white-striped uniform, he spends his days pining for his girlfriend and a ragtag gang of juvenile-delinquent friends. But finally, he plots his escape, crawling down a manhole and through the compound’s sewer system, at one point losing his pants and falling into a subterranean pit of Norway rats.

In the midst of his horror, one rodent catches the protagonist’s attention. With squeaks and squeals, it beckons him to follow, as if to say it knows the way out, and down a dimly lit tunnel, the duo eventually reach an exit. “Thanks, pal,” says Depp emphatically, before climbing up to his freedom—only to find himself delivered right into the hands of the jailhouse guards.

From the depths below, the rat snickers out a maniacal laugh. Once again, man’s ultimate foil.

PILES OF TRASH PROVIDE PRIME FOOD AND SHELTER.

It’s just one of many rat cameos in the oeuvre of Waters. The Lutherville native has commonly used rodents as comedic supporting characters—repulsed audiences or not. After all, he, too, has mixed feelings about the vermin, as he was recently reminded during a run-in at a local club.

“I went down the alley, and a thousand rats ran out, and it was really exciting, in a way—it felt like I was in, oh, I don’t know, the Middle Ages,” says Waters. “I hate rats, I’m scared of them, but I’m thrilled at how frightening they are.”

The way he sees it, we’re never going to get rid of them entirely, so we might as well learn to live with them, at least metaphorically speaking. He has no desire to harm rats. He’s certainly not feeding them, either. But if they can be used as a means of beating Baltimore’s bullies to the punch, so be it.

“You take it, you embrace it, you use it for humor, you make it your own, and it doesn’t have the same power anymore,” says Waters. “But if my house was overrun by rats and the landlord wasn’t doing anything about it, I’d get rat revenge. Because I don’t think that’s funny.”

And what exactly would that look like?

“Capture the rats, take them to the landlord’s house, and leave them there.”